Advice We Learned From Cobra Kai That You Should Totally Avoid

Amidst all the 1980s nostalgia, "Karate Kid" cameos, and absurd fight scenes, "Cobra Kai" manages to fit in more than a few simple but encouraging life lessons. Standing up for yourself, seeing the good in others, recognizing where you need to grow, letting go of past mistakes — these are all recurring themes of the Netflix series. At its best, the "Karate Kid" franchise has always tried to impart bits of wisdom and life advice as part of the story, and "Cobra Kai" keeps that tradition alive.

Well, most of the time.

There's also the other side of the show; a side filled with advice that's questionable at best and characters who, despite being held up as lead protagonists, repeatedly demonstrate highly questionable behavior. "Cobra Kai" is filled with flawed characters, which is part of the point, but those flaws often seem to be supported by the writing rather than condemned. A lot of the time, the show seems confused as to which ideas it wants to call out as problematic and which ones it wants to endorse. The result is something of a muddled mess — albeit, a highly entertaining mess.

Need examples? Look no further. Here's some advice we learned from "Cobra Kai" that should absolutely be avoided at all costs.

Running a small business is easy

Johnny Lawrence is a bad businessman.

He's constantly late on rent payments in the early seasons of "Cobra Kai," to the point that Kreese is able to steal the dojo right out from under him simply by going to the landlord. Early on, nearly every attempt he makes to recruit students is disastrous, and his dojo is usually saved by happenstance or the actions of others.

Yet, somehow, his business continues to thrive.

Admittedly, Johnny isn't paying rent on a dojo by Season 3, as his Eagle Fang classes are taught in parks and other public spaces. But the man still needs to eat, pay his own rent, buy gas, and cover all the other expenses that come with being a real adult. Los Angeles is not a cheap place to live, but he somehow manages to do just fine with a handful of students and, by Season 4, no apparent source of supplementary income.

This is not how things actually work, and it's not good business advice. Running a small business, especially something as niche as a karate dojo, is incredibly hard, and the fact that Johnny does as well as he does in "Cobra Kai" is just more evidence that TV obeys different rules than real life.

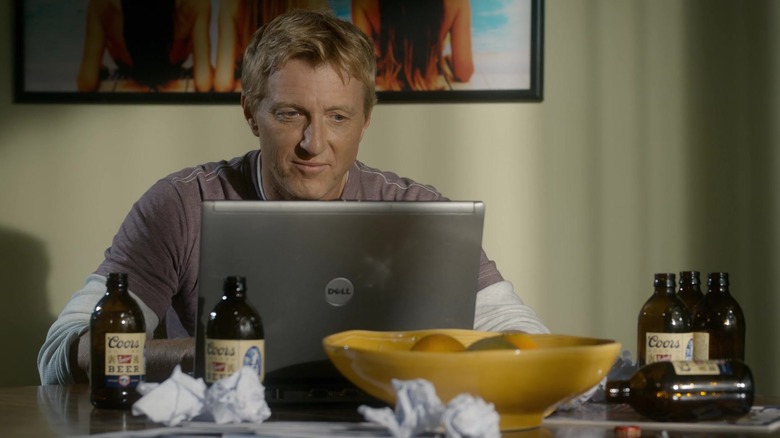

Drunk driving isn't that bad

Speaking of Johnny's bad habits, let's talk about his drunk driving — something he does multiple times throughout "Cobra Kai," even after going through arcs of apparent growth.

Obviously, the show doesn't praise Johnny for driving while under the influence. His alcohol-fueled spirals are shown pretty clearly for what they are — harmful and self-harmful behavior stemming from some serious emotional baggage. Yet, more often than not, Johnny's drunk driving is treated like it's ... fine. Yes, it's shown in a pretty negative light in the show's first episode, but later instances come and go without any real commentary. They're shot with the same semi-pitiable tone as his non-automotive binges, despite the fact that they are absolutely not the same thing.

Johnny never hurts anyone else with his drunk driving. In fact, he doesn't face any notable repercussions at all. Not every TV show has to be a public service announcement, but when your main character is portrayed as being a good person despite his flaws, showing him driving drunk with zero consequences becomes a problem.

All people deserve redemption

"Cobra Kai" has a basic compass for human behavior and morality — most bad people do bad things because of past pain or trauma, but they can be redeemed under the right circumstances. Anyone, at any point, can be either the bully or the bullied, the show seems to say. While there are a lot of nice, compassionate, and nuanced ideas implicit in that theme, the show occasionally takes things a bit too far when trying to give some of its characters redemption.

To be clear, "Cobra Kai" does a lot of flawed, nuanced character arcs quite well. Tory, Hawk, Johnny, and Daniel are great instances of this. Most people are better and more complicated than their worst deed, and it's important to show that when crafting characters on screen. But do we really need nuance for John Kreese and Terry Silver? Maybe not.

Not every villain has to be sympathetic, and not every bad person deserves multiple chances at redemption. It's understandable and even admirable that "Cobra Kai" has tried to add dimension to its bad guys, but there are limits. Not everybody deserves the benefit of the doubt.

Girls will like you just because

There is a lot of teenage romance in "Cobra Kai." It has always been a big part of the show, and there have been some genuinely cute moments and compelling relationships along the way. Then, there's Demetri and Yasmine.

At the start of "Cobra Kai," Demetri is firmly at the bottom of the high school hierarchy. He's dorky, unathletic, a bit socially awkward, and he doesn't seem interested in changing anyone's perceptions of him. Through the show, his training in Miyagi-Do karate raises his confidence and eventually earns him some respect with his classmates. That includes Yasmine, the cliché popular girl who previously was only interested in deriding Demetri at every turn.

In Season 3, Yasmine makes out with Demetri but remains in denial of her apparent feelings. There are hints that she likes him because he's ... different? And because he shows her compassion when everyone else is bullying her? Okay, fair enough. But then in "Cobra Kai" Season 4, she goes from hesitantly into him to head-over-heels, miss-my-dad's-wedding-in-Australia-for your-karate-tournament, flirt-with-you-aggressively-in-every-single-situation in love. It's a little jarring to say the least, mainly because "Cobra Kai" never explains why Yasmine is into him at all.

Clearly, Demetri's relationship with Yasmine is mostly intended for comedic effect, but that doesn't excuse it from needing an actual justification. It's totally fine for a guy like Demetri to get with a girl like Yasmine, and with the right writing, their relationship could actually be really cute. But instead, their story is about as deep as a cardboard sign with the words "the nice guy gets the girl because" scrawled across it in crayon. The result is a weird, uncomfortable dynamic that loses all of its potential fun factor and comedic charm.

Danger builds character

Johnny Lawrence is an idiot. This is a well-documented fact in "Cobra Kai." The appeal of his character is that, despite not being the smartest person in the world, he has a big heart and is able to make a big difference in the lives of kids because of his dedication and belief in them. We like Johnny — how could you not?

But Johnny still does really, really dumb things sometimes, and they often involve submitting his students to entirely unnecessary danger in the interest of imparting some vague life lesson. He's pushed them into pools with their arms tied. He's stuck them inside concrete mixers with actual concrete. He's trained them in abandoned warehouses and junkyards, and he's encouraged them to jump off buildings, all to make them confront their fears and push their limits.

There's a sweet idea buried somewhere in all those terrible decisions, but they are still, unmistakably, terrible decisions. Usually, Johnny's bad ideas end up having the desired effect, sending his students away feeling more inspired or confident in their abilities. But that's only because the light, family-friendly tone of "Cobra kai" doesn't allow for his plans to go wrong. What if Sam hadn't made that jump from one building to the next, and instead ended up flat in the alley below? What if the concrete hardened? The idea that danger is a necessary component of character-building fits with Johnny's more toxic values (though he would scoff at that word), but it certainly isn't good advice.

Everything was better in the '80s

The wheel of nostalgia never stops turning, and there's something undeniably cool about the aesthetic of the 1980s. The neon, synthwave look and feel that has been retrospectively attached to the decade is futuristic and fun, and recent years have seen a ton of modern movies and shows like "Stranger Things" dive deep into that aesthetic with great success. Because "The Karate Kid" takes place in the '80s, "Cobra Kai" is also packed with nostalgia and references to the era. Most of it plays into the vibe of the show in fun ways, but at times the show's glasses become a bit too rose-tinted.

"Cobra Kai" seems to reinforce the sentiment that certain trappings of modern life — technology, changes in media, a greater focus on emotional wellbeing, etc. — have had largely negative impacts on society. Kids are weaker and less likely to stand up for themselves, and music just isn't as cool as it was when Twisted Sister was on top of the charts. There's nothing wrong with nostalgia, or with choosing a certain aesthetic for your show, but no, everything was not simply better in the '80s.

Ignorance is funny

"Cobra Kai" tries with an almost painfully-exerted effort to not be a political show. It's villains are apolitical — high school bullies and mean-spirited, abusive adults — and while it features characters from a wide range of identities and backgrounds, it tries not to draw particular attention to any major issues of inequity or marginalization.

That can be okay; there's nothing inherently wrong with a show that wants to deliver simple, positive messages to as large an audience as possible. The problem is that "Cobra Kai" also constantly engages in a discussion of modern "woke" culture, gender pronouns, feminism, and other relevant social topics that push its apparent apolitical mission in curious and sometimes questionable directions.

Johnny is the biggest example of this odd tension. He's frequently portrayed as ignorant regarding other cultures, gender identity, and basically anyone whose experiences are different from his own. But this is all written off as fine — and even funny — because his heart is in the right place. At times, this comedy works pretty well, like when Johnny cooks a heavily Americanized Mexican meal for Miguel and his family, despite the fact that they are from Ecuador. It's cute, because it shows how hard Johnny is trying to be better and more open, even if he falls a bit short.

Other times, though, "Cobra Kai" plays ignorance as comedy in more problematic ways. Yes, people can be oversensitive, and actions speak louder than words — but words still matter.

All vegans are bad people

Sure, vegans are easy targets for jokes, especially in a show starring a Coors-chugging, hard-rock-loving carnivore like Johnny Lawrence. It's not false to say that vegetarianism and veganism have been co-opted by a certain subset of sometimes self-important, largely upper-class people, who've given the diets a pretentious reputation.

But how many tofu jokes can one show make before it's just too much? "Cobra Kai" seems intent on answering that question.

There are so many scenes in this show mocking vegan restaurants and hipster culture that it could be mistaken for a Joe Rogan podcast. Even John Kreese, a literal murderer and the epitome of villainy in the "Karate Kid" universe, gets to bash on some hapless tofu munchers and look heroic in doing so. It's a bit odd to see a bad guy with very few redeeming qualities portrayed in a positive light for dunking on vegans, and it makes a lot of the ensuing comedy feel a bit childish.

This is not a big deal, and a joke or two here about preppy rich folks shunning meat can absolutely play. But the hardened stance of "Cobra Kai" against anyone who doesn't eat meat feels ill-informed — and as far as advice is concerned, particularly for an athlete, a vegan diet is far healthier than what we've seen Johnny (whose idea of a garnish is crushed-up Slim Jims) put into his body.

Your teenage years define you

Not since Al Bundy reminiscing about his four touchdowns scored for Polk High has a TV show depicted a middle-aged man so hung up on his heroic exploits of yesteryear. Flashbacks, cameos, and unresolved rivalries are necessities for a show that's based on decades-old movies. At the same time, the series spends a lot of time trying to teach its characters that the past doesn't define them. This is a lesson Daniel and Johnny hear over and over again, making it one of the larger themes of "Cobra Kai."

Unfortunately, that message is undercut at nearly every turn by the actual events of the show. Dialogue about how the past doesn't define you falls flat when every conflict that takes place is a conflict from the past, when every enemy is an enemy from the past, when every ally is an ally from the past, and so on. Specifically, most of the story springs from Daniel and Johnny's teenage years, as that's when the "Karate Kid" films take place. While science says your teenage years are incredibly formative, "Cobra Kai" makes them absolute. The result is a show that claims that people are more than what they did in their youth, but which only shows adults dealing with unresolved issues from their youth.

The contradiction here certainly doesn't ruin "Cobra Kai," but it feels odd every time the message being delivered contradicts what's actually happening on screen. There are hardly any plotlines for the adult characters that don't have their origins decades in the past, and that hurts the show overall. It's true that your past doesn't define you, but "Cobra Kai" can't seem to get that message right.

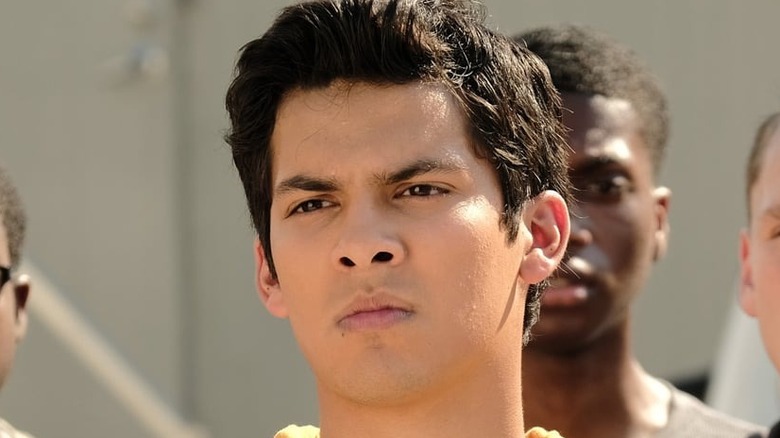

It's okay to drive without a license

Usually, Johnny is the one encouraging kids to do dumb and dangerous things in "Cobra Kai." But in season 4, Daniel takes a turn in the bad influence driver's seat by putting Miguel in the literal driver's seat. He encourages — even pressures — Miguel to drive across L.A. after fixing his mom's car. Here's the thing, though: Miguel doesn't know how to drive. It's unclear if he even has a license at the time.

Clearly, this is a bad idea. From the second he gets behind the wheel, Miguel makes it very clear that he has no idea what he's doing. He then immediately goes out on busy roads with zero driving experience and, thankfully, doesn't cause any horrible accidents or additional damage to his mom's car. It's bad enough that Daniel makes him take to the streets with no training, but it's even worse that he presumes without asking that Carmen would be fine with her son driving her car through the city.

This is not Daniel's finest moment.

While the scene is played as a cute coming of age moment sparked by the kind guidance of a mentor figure, this is just bad advice. Do not drive if you do not know how to drive.

Instinct is more important than facts

"Cobra Kai" is not a terribly serious show. It's fantastical and often outwardly comedic in tone, and that's all part of the appeal. But put together enough lucky coincidences, and you run the risk of espousing simply bad advice. In other words, "Cobra Kai" repeatedly enforces the idea that gut instinct is more important than logic and fact, by rewarding characters for acting in illogical ways.

This ties into some of the previous entries on this list, such as Johnny driving drunk with no consequences, Miguel driving unlicensed, and Johnny using dangerous training exercises to teach his students character. It also extends to plotlines like Johnny's attempts to help Miguel walk in Season 3 via DIY chain hoists and Dee Snyder concerts, but which generally seem to ignore any actual medical expertise.

There is a lot of value in trusting your instincts, and that theme fits well with the overall story of "Cobra Kai." But because Johnny's instincts are often terrible, the show frequently toes the line between inspiration and outright bad advice. Science, data, and facts matter, no matter the impossible good fortune of some TV characters.

Adults don't need therapy

This advice is more implied than firmly stated, but it still lives in the background of "Cobra Kai." Johnny Lawrence is in desperate need of a therapy session. He has a ton of unresolved issues stemming from his difficult childhood and the various abusive male figures who played a role in his early life. He shows signs of alcoholism. He clearly has a lot of internalized self-loathing. And while Johnny has come a great way since the beginning of the show, he'd surely benefit from professional help.

Unfortunately, that doesn't seem to be an option in the world of "Cobra Kai." The only characters who have any experience with therapy are Tory (for whom it seems to help a great deal) and Terry Silver (for whom it simply buried past traumas and postponed the return of his more aggressive qualities). The inherent message here is that therapy can be helpful for troubled kids, but it isn't going to help adults; they need to do that on their own.

This is bad advice. Johnny Lawrence should go to therapy. Terry Silver should go back to therapy. Half the characters in this show should probably be in some sort of therapy, but instead they address their issues by tornado-kicking each other in the head.

Don't worry, you won't get arrested

There are more teenage hijinks in "Cobra Kai" than a 1950s public service announcement. Teens are constantly drinking underage, breaking into each other's houses, trespassing on private property for street fights, driving without licenses, and committing all other manner of youthful, illicit deeds. It's part of the charm — but at a point, viewers have to wonder why none of these kids ever seem to get in real trouble.

Yes, Robby gets arrested after nearly paralyzing Miguel, but that's about it. Police are almost never called, and when they are, little happens (well, to anyone but Kreese). The question of whether or not that's a good thing is debatable, but it's definitely far-fetched. Breaking the law usually comes with consequences, even for young people, and especially for young people from lower socio-economic strata.

Obviously, a show can't happen if half the cast is constantly in and out of juvie, but that doesn't make the lack of repercussions for the teen antics on "Cobra Kai" any more realistic. If you are a teenager, this is not the advice to follow.

Every viewpoint is somewhat valid

If "Cobra Kai" has a single main them, it's balance. Johnny and Daniel exist as two clear foils, opposite but similar in nearly every way, constantly orbiting each other. Their students are able to achieve great things by reconciling both of their philosophies and perspectives, creating new and balanced ways of thinking and fighting. It's a meaningful and admirable theme, but in the show's yin-yang efforts to show the good and bad in everything, it occasionally goes a bit too far.

John Kreese is an abusive, evil man. His strict doctrine of no mercy does not deserve to be endorsed in any capacity. Sure, there are times in life when striking first may be the right move, or when some other part of his Cobra Kai philosophy seems like a good idea, but not in the way he uses it. Narratively, there may be some appeal in showing the "good" of Kreese's karate, but following his teachings in any way is straight-up bad advice.