Things In West Side Story Only Adults Notice

Ever since the announcement of Steven Spielberg's "West Side Story," fans of the original Broadway production and subsequent film had one question: Do we really need another adaptation? After watching the film, critics have resoundingly answered, "Yes."

Not only does this updated version of Stephen Sondheim's masterpiece boast a more diverse cast, but it also ditches a slew of outdated caricatures of Puerto Ricans from the original film. Spielberg's version of the story rights many wrongs, while its "Romeo and Juliet" inspirations hold firm. Stephen Sondheim died shortly before he could see the new adaptation premiere, but his legacy lives on through the film's vibrant vocals, chilling performances, and the stunning choreography of the 2021 reimagining.

As a result of the many mature topics portrayed in any incarnation of "West Side Story," there are a host of details that kids may not notice while watching the updated film. Whether it's complex topics like gentrification, sexual content, the futility of gang violence, or simply an OG cast member's involvement in the new film, here are all the spoiler-heavy plot points adults are more likely to appreciate in 2021's "West Side Story."

NOTE: This article (and its source material) include topics of suicide.

Our OG Anita strikes again

1961 was quite a while ago, and as a result, when it came time to cast Spielberg's iteration of "West Side Story," a large number of the cast had already died or retired. Luckily for fans of the franchise, original Anita actress Rita Moreno was more than up to the challenge of appearing in the new movie. Even more, her character provided the blueprint for the film's most significant deviation from its original story. While the patriarch of the 1961 "West Side Story" is Doc, the focus shifts this time to Moreno's Valentina — Doc's Puerto Rican widow.

Born in 1931, Moreno was 30 years old when she was cast in Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins' classic film. Although she had appeared in more than a dozen films and TV series (including the 1952 classic "Singin' in the Rain" and the 1956 Oscar juggernaut "The King and I"), many had titles like "The Fabulous Senorita" and "Latin Lovers," and Moreno was unhappy with what she felt were stereotypical roles. After an Oscar-winning performance provided her breakout in "West Side Story," she went on to become a Hollywood legend, spending the next six decades appearing in everything from the Mike Nichols film "Carnal Knowledge" to Broadway hits (1975 Tony Best Actress for "The Ritz") to becoming a welcome face on children's programming ("The Electric Company," "Sesame Street," "The Muppet Show") and adult series ("Oz," "Miami Vice"). Now 89 years old, she recently headlined the Netflix reboot of "One Day at a Time," playing the feisty Cuban grandma during its 2017 – 2020 run.

Her newly-reimagined role in Spielberg's "West Side" turns out to be precisely what the film needs for grounding itself in the opposing worlds of Tony and Maria while offering a clever parallel for the young, star-crossed lovers. Like her original character Anita, Moreno's Valentina is spunky in her own way, but she also delivers some of the film's most emotional, hard-hitting moments.

While young musical fans who have seen the original '60s version may not realize the film's original Anita plays Valentina, they are once again in the presence of a "West Side Story" icon — and trailblazing Hollywood royalty.

Back to the '50s

Like the original film and Broadway show, this updated "West Side Story" takes place in the mid-1950s. Beyond the original show's 1957 premiere date, the film teases its time period with a number of historical references, clothing styles, and industrialization of what would later become the Upper West Side (or UWS, if you're a New Yorker on the go). However, despite all these time period hints, the greatest mid-'50s signifier might be the opening shot, where you can see ongoing demolition and a sign promising the arrival of Lincoln Center.

While the performing arts hub didn't break ground until 1959, the original movie musical had filming underway at that point — managing to catch history on-screen. In the opening scene of the 1961 film, fans can actually see the real rubble of the original Lincoln Square that would later become Lincoln Center. So, it's only fitting that the remake would pay homage to that historical significance with manufactured rubble and a "coming soon" sign to recreate the active construction site that made a memorable cameo in the original.

From gentrification to Lincoln Center

While younger viewers have always been thrilled by the romance and surface-level tragedy of "West Side Story," the reality of the story goes much deeper — and it's something that New York City is still dealing with today, more than a half century after Jerome Robbins, Leonard Bernstein, Sondheim and author Arthur Laurents came together in the late '40s to originally conceive what would become "West Side Story." At the heart of every conflict in the musical is one thing: gentrification. These are the consequences of displacing marginalized communities to "class up" neighborhoods, resulting in the erasure of culture and displacement of low-income families who have lived in that area for generations.

As "West Side Story" depicts, the modern-day Upper West Side came about as the result of thousands of Puerto Rican immigrants and other locals being forced out of their homes. It's a cycle that continues, as today it is common for people who have lived in areas like Brooklyn and Harlem their entire lives to find themselves priced out of their homes when higher-income people move in, bringing with them new amenities that cater to their tastes, often at the expense of the vibrant communities built by their predecessors.

Of course, this isn't a problem unique to New York, and neither are attempts to simply "buy out" those being evicted (or sometimes, take their land through eminent domain). The new "West Side Story" hints at this when we see Anita rip up a relocation check; according to the New York Times, the relocation money promised to displaced residents never actually came.

The West Side's muddied past

Just as gentrification remains a problem long after the events depicted in "West Side Story," it had been one for hundreds of years prior as well. Europeans took over the land from its indigenous Lenape residents, one of countless tales of America being taken from native Americans.

Following the so-called "sale" of Manahatta in 1626 to the Dutch, by the 1800s Dutch communities migrated to the pre-Upper West Side area. They were in turn pushed out by rapidly developing technology and the easing of transport. The modern era began with the rise of industrialization and the creation of the subway system, and by the start of the 1900s, many Puerto Rican immigrants had settled in the area — leading eventually to the displacement depicted in "West Side Story."

Additionally, much of the film takes place around 66th street, but at the time, that area was a largely Black neighborhood. While kids and perhaps even many adults may not be familiar with that element of the Upper West Side's history, it's an essential one that remains largely absent from the series. "West Side Story" elects to focus on only two of the feuding groups that existed at the time, but as is often the case, reality was a little more complex than that.

Outside of a few Black characters here and there, we miss out on that rich history in the film. All in all, the deep (and often heartbreaking) history of the Upper West Side is much more expansive and complicated than perhaps any film or musical could possibly relay.

This language doesn't fly anymore

When it comes to comparing the 1950s to modern-day America, it's reasonable to say that society has come a long way. While certain racial slurs might be largely eradicated from modern speech, "West Side Story" remains a period story set against a tense, hate-fueled clash of colors and creeds at a key time in the history of New York. To accurately portray it means that certain words and phrases must be extracted from the dustbin of history — hopefully so modern audiences can learn from our collective past, to never repeat it.

Much of this language includes slurs against the film's Puerto Rican characters. For adults, they may hear such dialogue and recall similar things being said by some around them in their youth. For today's younger viewers, perhaps it's an opportunity to have a cross-generational conversation about why such hate-fueled speech deserves to be left in society's rearview mirror. As the lyrics to one of the franchise's trademark songs have sung for decades, "Life is all right in America/If you're all-white in America," but even though they are both telling the same tale, perhaps "West Side Story" 2021 debuts to a more tolerant world than 1961's "West Side Story" did.

Welcome to the Hellmouth

If you grew up in the '90s, or are a fan of its classic TV series, perhaps the word "Hellmouth" isn't a new vocabulary word. "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" introduced a generation of wannabe slayers to the term as paranormal slang for the hotbed of seedy activity drawn to Sunnydale.

In "West Side Story," the lieutenant calls the Jets' and Sharks' turf a Hellmouth — a term that actually dates back hundreds of years, a concept in Anglo-Saxon art around the 5th century, long before Joss Whedon ever got ahold of it.

Like Buffy's iteration of the ancient term, the belief proposed that the portal to hell opened inside of a monster's mouth. Like many Christian ideologies, however, it's believed that mythology inspired the concept. In this case, we may owe the rich history of the Hellmouth to the Norse mythology's art depictions of the battle between Víðarr and Fenrir. Víðarr is the son of the all-powerful Norse god Odin (think the Norse version of Zeus), while Fenrir is a wolf-like god and son of Loki.

Wherefore art thou Tony?

For anyone who hasn't had to recite Juliet's death monologue in high school literature class, they may be surprised to discover that "West Side Story" is an adaptation of one of William Shakespeare's most enduring works, "Romeo and Juliet." Often classified as the Bard's most romantic (and tragic) written work, "West Side Story" takes a few creative liberties on the original tale. However, the gist is the same: Girl has the hots for boy, boy has the hots for girl, the folks around them feud — and a lot of people die.

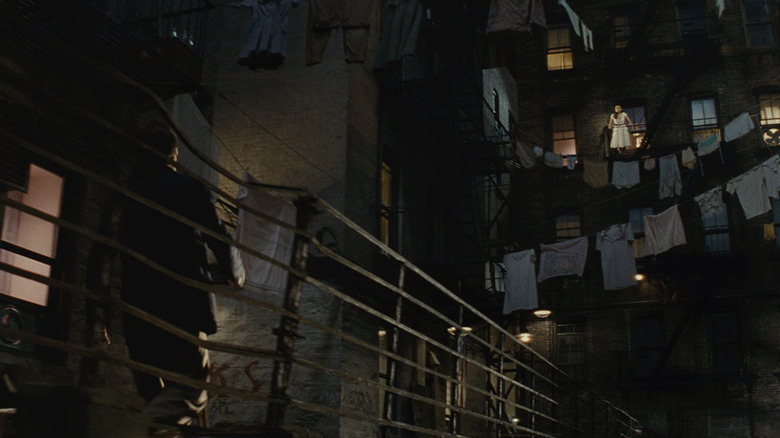

Most obviously, Tony and Maria's duet "Tonight" is based on the balcony scene between Romeo and Juliet (you know, the whole "O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?" schtick). The musical's ending also stems from the double suicide of Romeo and Juliet, which stems from an unfortunate case of miscommunication. In "West Side Story," Maria is saved from Juliet's fate. But Tony perishes, just like Romeo, during a blood vendetta between the Jets and the Sharks, similar to the Montagues and Capulets of "Romeo and Juliet."

Pump the brakes, kids

To younger people watching "West Side Story," Tony and Maria's whirlwind romance may seem like an epic, enviable love. In reality, they're two inexperienced kids enamored with the idea of love. Only a few days pass between the moment Tony and Maria meet and they express epic devotion towards each other. Look more closely from a modern context and it's hard to ignore that they are risking life, limb and ostracization while barely knowing a thing about each other besides they both enjoy dancing and making out.

It's important to keep in mind that in the mid-'50s, the average age of marriage hovered around 20 for women and mid-twenties for men. Today, both have gone up nearly a decade. So, while it may seem like Tony and Maria are moving awfully fast, in the era being depicted, teens were pressured by society and peers to find their soulmate much more quickly.

Sure, a 2021 filmgoer might think someone needs to wave a bright red flag when Tony starts talking "forever" the night they meet. Their supposed love appears surface-level at best; the gorgeous song "One Hand, One Heart" even features wedding vows.

To a modern audience, it all feels a bit too much, too soon — it also raises serious questions about whether Maria and Tony would have lasted, had they remained together and married. It's a good opportunity, perhaps, for another cross-generational conversation after the film, one about whether the world was really better when people married younger and often with less familiarity (in the mid-'50s, fewer than 20 percent of marriages ended in divorce; although numbers are often debated today, it is generally accepted that divorce is far more common today). Much like the ending of "The Graduate," a film that arrived seemingly at the sharp-left turn between these old and new ways of thinking, the question remains: after love has swept a couple off heir feet, do they have what it takes to truly find happily ever after?

Things get frisky between the sheets

Whether you're talking about the 1950s or the 2020s, one thing both decades have in common is that people probably wouldn't immediately sleep with someone else after that person had just killed their brother. But hey, teenage hormones remain the same, regardless of the decade.

To adults, it is clear that Maria and Tony sleep together after Tony admits he killed her brother — and they do more than simply rest their eyes. To younger viewers (especially those who haven't had "the talk"), it might simply seem like all that making out has bonded them very quickly. While Spielberg doesn't exactly seek out subtlety in his story beat, their union isn't NC-17 explicit either, so it might just seem like Maria and Tony innocently cuddled in bed.

From positioning to missing articles of clothing to their body language when they wake up in the morning, however, the message will be clear to most. Back in the '50s, many people would deem this behavior as scandalous — but religion or no religion, teenagers weren't always as innocent as your grandparents might try and tell you.

All's not fair in love and war

"West Side Story," like "Romeo and Juliet," is less a love story than a warning about feuds and gang activity causing senseless deaths of young adults. So many characters in all the franchise iterations die unnecessarily, fueled by a dangerous mix of pride, peer pressure and racial animosity.

A meaningless turf war manufactures the endless fight between the Sharks and the Jets, egged on by adults whose animosity stems from ignorance, intolerance and a misplaced idea of ownership over an area. Even if one side were to eventually end up reigning supreme, what exactly would that solve? The police, and affluent individuals ready to move into the neighborhood once it's cleaned up, seem to be the only ones who realize that these miscreants are fighting each other rather than their real archenemy: gentrification.

Chino (outside of Tony and Maria) is the only one who acknowledges how stupid this all is. Yet, despite calling the rest of the Sharks out for this pointless feud, Chino is the worst of them all. He knows how senseless this battle of pride is, but participates on his own accord anyway — throwing his entire life away for petty revenge. You could argue that Tony also participates while acknowledging its foolishness. However, Tony at least makes an attempt to stop the fighting multiple times, and only participates when people start dying. At the end of the day, both gangs are perishing over turf that won't even exist in a few years.

Glorifying suicide

The final acts of "Romeo and Juliet" and "West Side Story" have always been dicey, given the implications of Romeo and Juliet's suicides in the source material and Tony's intentional death in "West Side Story." Of course, Tony's death needs to happen — it's an adaptation of a classic, after all. Since the debut of "Romeo and Juliet" in the late 1500's, many have viewed the tragedy as an ultimate expression of undying love — and for nearly as many years, others have seen it as problematic.

In a 2021 "West Side Story," do we really need Maria brandishing a gun around in the air, scream-asking if there are enough bullets to kill her, too? Couldn't Maria have, instead, lamented that even if she were dead, she would have wanted Tony to live — and that she knows he'd want that for her, too? This latest film could have perhaps included a line or two of dialogue (possibly from Valentina) that the best way to love Tony would be to remember him and celebrate his memory by living the life he will not.

It's not a matter or propaganda, it's not a matter of political correctness, to question the 16th century-born notion that ending one's own life is the best way to show you can't live without someone. When you consider how many people will see "West Side Story," and the high likelihood that some may be on a precipice of their own, such things seem worthy of consideration.

In the end of 2021's "West Side Story," Maria doesn't shoot herself, as she threatens. Still, more could have been done to de-sensationalize, de-romanticize, and perhaps de-glorify Tony's death based on the words and actions of other characters, and how they respond to his actions.

One of the multitude of ways society has changed between 1961's "West Side Story" film and 2021's remake is that there is a substantially-increased sensitivity around suicide and how it impacts those in the orbit of the deceased. Perhaps this should have been among the modern ways of thinking Spielberg embraced while plotting out his remake, which could have resulted in a "West Side Story" that better addressed the end of Tony.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).