Everything Women Talking Gets Wrong About The True Story

"Women Talking" is the latest movie by acclaimed filmmaker Sarah Polley. Like much of her early work both in front of and behind the camera, the film is an intimate, raw portrait of personhood –- what it means to be this individual, in these relationships, with these struggles. In her examinations of singular existence, Polley often takes us on a journey of a grander scale as well. "Women Talking" focuses on the experiences of these particular women, yet in doing so also reveals something about the lives of all women.

The film received a best picture Oscar nomination this year despite getting only one other nod for Polley's adaptation of the novel by Miriam Toews into the screenplay. It's Polley's second nomination in this category, an accolade, as a writer without a credited partner, she shares with only six other women.

The process of adapting a work for the screen is inherently reductive, however, as complex stories must be streamlined to fit into an acceptable running time. Some items will be combined while others are cut entirely, but ideally, these changes don't detract from the story. Let's take a look at "Women Talking" to see where the alterations were made and if they served the story well.

Warning: The following discusses events of sexual violence and depictions of its aftermath. If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Women Talking is based on the 2018 novel by Miriam Toews

"Women Talking" is adapted from the novel of the same name by Miriam Toews. Inspired by the horrifying news of sexual assaults among a religious community in Bolivia, the book is nonetheless a work of fiction. The real-world attacks took place within a segregated society of Mennonites living in Manitoba Colony, Bolivia. As a woman raised in a Mennonite community in Canada, Toews used firsthand knowledge in creating a similar world to task the women with deciding what comes next.

To this extent, the film is actually a very faithful adaptation. Both are centered around 48 hours when the men are gone to bail out the accused, leaving the women able to meet and discuss their options. The novel is structured as meeting minutes taken by August, a mild-mannered schoolteacher for the colony boys.

August still exists in the film, played by Ben Whishaw, and he's still taking the minutes (as the only literate person in attendance). However, the narration has been given to Autje (Kate Hallett), a teenager and survivor of the attacks who acts as not only a participant and stakeholder of the meeting but a critic and historian of it also. She is telling the story to the as-yet-unborn child of Ona (Rooney Mara) — the result of Ona's assault.

It's a small but impactful change, and yet beyond that, only the condensing of some very minor characters and details separates the film from its source material.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

What follows is an act of female imagination

Following an opening title card summarizing the events leading up to "Women Talking" is a single statement: "What follows is an act of female imagination."

On the surface, these words may seem to indicate that the film is a fantasy that can be dismissed as a lark, but to think so superficially about the film is to do everyone a disservice –- the filmmakers, the novel's author, the real women subjected to such villainy, and oneself.

When the real attacks began, women would awaken bruised, bloody, and in pain. Their nightclothes were ripped, but they would have no memory of what happened due to the cattle tranquilizer spray the rapists used to knock out entire households. Living in a strict patriarchal society, the victims -– some merely prepubescent girls -– would confide the details to their fathers or husbands, who initially dismissed it all, even the physical evidence, as "wild female imagination."

Using the phrase "an act of female imagination," both in the novel's author's note and the opening seconds of the film, therefore, upends the words used to gaslight these victims and turns them into empowerment instead. Rather than being victimized twice over by not having their own testimony believed, women are using their imaginations to regain power, authority, and agency over their own lives. They will decide what comes next.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

August is a fabrication, but no longer the storyteller

For the purpose of providing exposition in "Women Talking" surrounding the lives and dynamics of the women and community, author Miriam Toews created the character of August. A stand-in for the author herself, August provides both an insider's and an outsider's perspective. He, as the taker of the minutes, is their storyteller. Director Sarah Polley doesn't think he has that right.

August's presence still serves a purpose in the film. He still takes the minutes. He is the benchmark for the inevitable "Not all men" defense. He is a man in love with his childhood friend Ona, longing to be her protector and broken up at the violations these women have endured. He is an objective source of information the women do not possess, such as maps and practical knowledge. Plus, he's the hope for the future of the colony.

The narrator's role in the film, however, is given to Autje. She is a victim of both the new violence to plague their community — the sexual assaults — and the old violence that has always lived among them — the domestic abuse. She is old enough to be someone who would've understood the impact of what happened to her but young enough to represent the promise of new beginnings. She has a horse in the race, so to speak, and is better equipped to tell the story.

Differing accounts of capture

In the film "Women Talking," it's revealed that Nietje (Liv McNeil), whose mother hanged herself after the assaults kept happening, awoke one night and saw her attacker's face. He scrambled out the window but was caught and named his accomplices. The men were then locked in a shed until the elders could decide what to do with them.

This very closely aligns with a couple of accounts detailed in a Time article from 2011, in which one woman briefly woke up while drugged and another caught two men entering her house. Another article from the BBC claims that colony elders discovered the scheme when one man from their community was sleeping unusually late. The elders then decided to follow him since the colony eschews electricity and people generally aren't out after dark.

Regardless of which series of events is true -– perhaps they both are -– it's fair to suggest that Polley depicted the discovery as belonging to the women to maintain their agency throughout the film. There's nothing inherently wrong with the colony elders capturing the culprits, but the point of the narrative is that the women are capable of saving themselves. At every opportunity, Sarah Polley's directorial choices keep the agency of action with the women, never with the men. It's the women's story to tell, their fight to win, their dilemma to ponder, and their decision to make. Everything in the film must be on their terms.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Only eight men were convicted

True, not all the men in the real circumstances were involved in these crimes –- not even most of them. Still, even those who were not involved chose not to believe the victims, gaslighting them by saying they were crazy or dreaming — or that Satan had done it. They chose to blame the women for their own rapes by saying it was punishment by God for their sins. These same men said that since the women were unconscious, they couldn't possibly be psychologically damaged from the attacks.

Despite that last statement being patently ridiculous, it's also incredibly destructive. Men choosing to believe that women are "fine" after such a harrowing event because they continue to laugh with their children or do the housework (or whatever) undermines women's humanity, perseverance, and pain. Furthermore, it's the belief that only a "few bad apples" among men commit terrible atrocities that allow these assaults to continue unabated.

So while in truth there were "only" eight defendants from Manitoba Colony, the film explicitly refrains from giving a number. The number is not the point. Director Sarah Polley explicitly wanted the film to address the idea of societal sins and complicity. She tells us that all the men have gone to bail the accused out of jail because all of them, in one way or another, are complicit in the system.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Smaller community, more victims

The unnamed Mennonite colony in "Women Talking" is much smaller than the actual Manitoba Colony in Bolivia where the real rapes occurred. While the film states that every woman in the community has been attacked, there were 130 accusers named in the charges brought against the offenders in Bolivian courts. However, prosecutors said the true number of women who were sexually assaulted could be twice as many as reported, simply because many didn't want to admit to being raped.

This is sadly a very common occurrence, as RAINN reports that most women who are victims of sexual assault never report the crime. Beyond that, the very strict doctrines of the Mennonite community ensure that the percentage of victims who refuse to report or admit the attack is even higher. There is the fear of stigma, of being shunned, of losing social status, or even of being forever ruined in the eyes of God and their church.

This is true for all women, but for those living in an environment that is insular and segregated from the rest of the world, being ostracized or excommunicated can feel like a death sentence. Time reports that many of the women in the real Bolivian community couldn't even speak the local language, instead converse only in the Low German dialect Mennonites have used for centuries.

However, the fact that this is all so relatable explains Polley's decision to visit this violence on the whole colony: for the simple reason that this violence is everywhere. Sexual assault –- and all the torment that comes with it –- affects women universally.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Arrested for their protection?

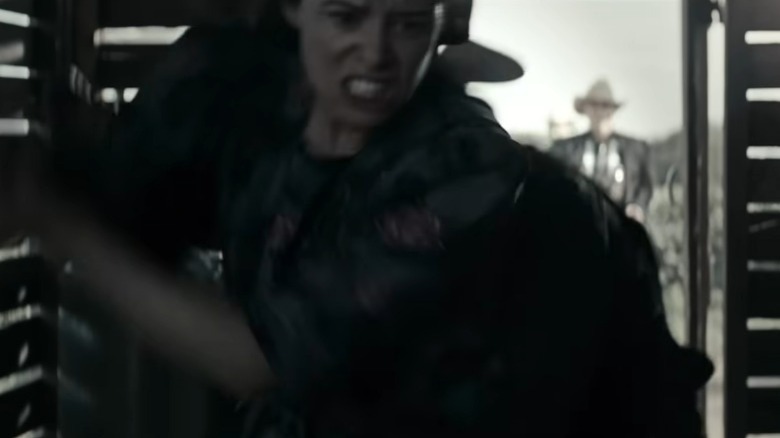

In "Women Talking," Autje narrates that the elders turned the accused men over to the police to be "arrested for their own protection." Given the accompanying scene of Salome (Claire Foy) attacking the men with a scythe (we learn later that she'd just found out her four-year-old daughter had been infected with a venereal disease), it seems likely that the men are in danger. Still, it also feels a bit insulting that the elders are more concerned with protecting the men than they ever were with protecting the women and girls like four-year-old Miep (Emily Mitchell).

In actuality, the Manitoba Colony elders were simply overwhelmed with the scope and nature of the crimes and thus turned the men over to the police because they didn't feel equipped to deal with it on their own.

Of course, it's true that some of the husbands and fathers of the victims were so outraged at what happened that they were furious enough to seek out their own revenge against the perpetrators. Some even threatened that if the men were released from jail and attempted to rejoin the colony, they would be killed. Defense attorneys even used these statements as evidence that their clients' confessions were coerced.

So there might be some truth to the idea that the men were safer in jail than locked up in a shed on someone's farm. It would certainly make a lot of sense. However, it's not the official story.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Deliberately vague location

While the actual location these crimes were committed is named after Manitoba, Canada, the real Manitoba Colony is located in the lowlands of Bolivia, where thousands of Mennonites immigrated to farm the land more than a hundred years ago. As they were in the southern hemisphere, travelers would use the Southern Cross to aid them in celestial navigation, as the women plan to do in "Women Talking."

However, there is also a census taker who drives through the countryside, asking families to come out and be counted for the 2010 census. This could imply that these people live in the United States and the northern hemisphere, where the North Star is the celestial navigation waypoint. Is this a flaw?

The novel is deliberately vague about the women's location, giving the colony a fictional name and only ever really talking about places August has been, but not in relation to where they themselves are. The movie takes this further by not naming the community at all. Moreover, the map August provides the women is practically a bare expanse with no names anywhere.

These tactics are all probably related to director Sarah Polley's desire to reflect the universality of these experiences. Yes, it happened here, in this community, but it could happen anywhere, to anyone. It affects all women, and it is tacitly supported by all men. These are recurring themes that gibe with Polley's focus on global cultural toxicity. Symbolically, it didn't just happen there — it happens everywhere.

Nothing has changed

In the film, the women must decide if they will do nothing, stay and fight, or leave. The decision matters, as do the inciting events that necessitated it, but as Bill Newcott explains in his review for The Saturday Evening Post, the drama and tension of the film come from the discussions, and that is where it spends almost all of its focus.

Faced with such a high-stakes decision, the women contemplate the very nature of forgiveness. They define what it means to fight, what they would be fighting for, and what kind of community they would like to live in. They consider the roles they play in their community compared to the men, and dare to dream for parity in a world built on subservience.

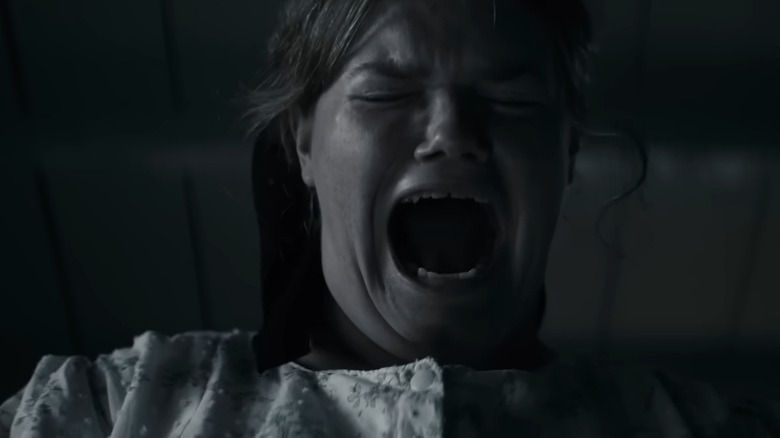

The movie isn't interested in showing the attacks, offering only glimpses into the bedrooms of different victims reacting to the horrors. Additionally, once the decision is made, everyone acts quickly so as to be gone before all the men return. The majority of the film, then, is spent in the barn's loft, talking, fighting, crying, healing, and hurting.

Sadly, the real women who suffered these horrific attacks did not leave their homes –- at least not en masse. They did not get a chance to talk about what happened, and most weren't able to testify against their attackers. None of them have been offered therapy. Polley's film hopes for a better future for these women — and for all women.