Who Does Florence Pugh Play In Oppenheimer?

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

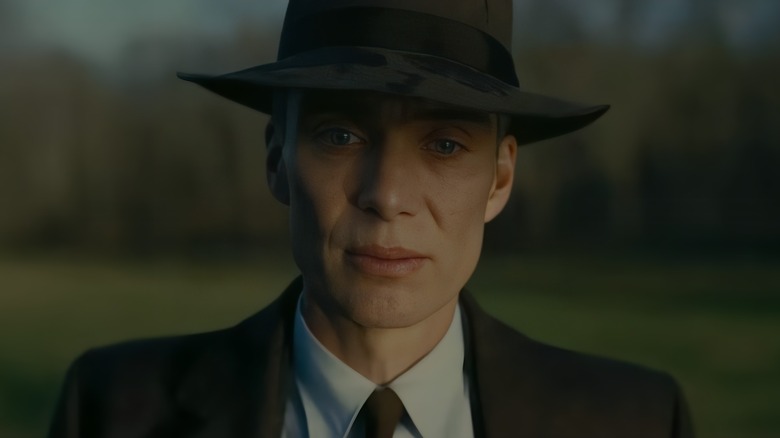

With his upcoming wartime drama film "Oppenheimer," Christopher Nolan is setting out to portray the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the man responsible for introducing the world to the nuclear bomb. The titular role is filled by Cillian Murphy, a longtime collaborator of Nolan's.

Robert Oppenheimer alone lived a life that could fill several movies, but Nolan has filled his picture with those who orbited the infamous scientist, from fellow academics who worked on the enrichment of heavy elements for the atomic bomb to people who enriched his personal life.

The latest trailer for "Oppenheimer" shows off the main cast of the film in full, including a role played by "Midsommar" and "Black Widow" star Florence Pugh. Though shown only briefly, Pugh can be seen looking up tearfully at another actor.

Pugh has been confirmed to play the role of Jean Tatlock, a psychologist who was romantically involved with Oppenheimer and led to his political awakening but also, ultimately, to his downfall. So who, exactly, is Tatlock? A complicated and ultimately tragic historical figure, Tatlock left an indelible impression on the father of the atomic bomb.

Florence Pugh portrays communist psychiatrist Jean Tatlock in Oppenheimer

Florence Pugh will appear in Christopher Nolan's upcoming "Oppenheimer" in the role of Jean Tatlock, one of the most important and influential people in the life of nuclear bomb inventor J. Robert Oppenheimer, who is played by Cillian Murphy.

Tatlock was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party of America (CPUSA), which had seen a surge in membership as Americans witnessed the barbaric rise of fascism in Europe that led to the horrors of World War II. But the Party had also softened its historic opposition to electoral politics and embraced candidates like Franklin Roosevelt. It was in this milieu, known as the "Third Period" that Tatlock entered leftist politics, and she was introduced to Oppenheimer at a Communist fundraiser held by his landlord.

Oppenheimer met Tatlock in 1936. She was still a graduate student at Stanford, where she studied psychology. But thanks to her political leanings, she would help to spell the end of the physicist's respected status in the annals of American government.

Tatlock and Oppenheimer reportedly enjoyed a passionate but arhythmic romance, as recounted by historians Patricia Klaus and Shirley Streshinsky in the book, "An Atomic Love Story: The Extraordinary Women in Robert Oppenheimer's Life." Though Tatlock may have been queer, describing her sexuality in a conflicted manner, she became romantically involved with Oppenheimer after their introduction. However, although he proposed twice, she declined to marry the scientist. The two continued to see each other until 1943.

Jean Tatlock awakened Oppenheimer romantically and politically

Whether Jean Tatlock influenced J. Robert Oppenheimer to embrace leftist politics remains a matter of dispute. In general, he was a political atheist and is said to have been so far removed from politics that he only learned about the stock market crash of 1929 which precipitated the Great Depression several months after the fact. But the rise of fascism caught his attention. As a Jew, it was impossible for him to ignore the unfolding genocide committed by the Nazis.

As his political consciousness grew and his romance with Tatlock blossomed, Oppenheimer increasingly espoused sympathies for the left. While he refused to label himself a communist, his inner circle grew to include many CPUSA members, and he hosted philosophical forums on communism at his own home. He considered himself a "fellow traveler" with communist causes, and a fellow academic stated that their goal was to insert leftist planks into the New Deal (via Atomic Heritage Foundation).

None of these affiliations prevented the United States government from selecting Oppenheimer to head up The Manhattan Project. But they would ultimately prove to be a black mark in the eyes of the government as America hardened its stance against communism after the war. It was the apex of the McCarthy era, and many prominent members of society were subject to scrutiny for perceived communist sympathies. Among them was Oppenheimer, whose relationship with Tatlock was invoked as evidence that he was secretly a communist. He was called to a hearing before the Atomic Energy Commission in 1954.

Ultimately, President Dwight Eisenhower demanded a "blank wall" between Oppenheimer and any state secrets to which he had previously been privy.

Jean Tatlock met a tragic end

Jean Tatlock suffered throughout her life with clinical depression, describing "tortures of self-consciousness" while an undergraduate student, as noted by Klaus and Streshinsky. She struggled with mental health for the remainder of her life.

On January 5, 1944, Tatlock was found dead in the bathtub in her San Francisco home near Berkeley. A suicide note was found by her father, and the coroner's office found barbiturates, salicylic acid, and chloral hydrate in her system. The death was pronounced a suicide.

Because of her connections to radical politics and to one of America's most valuable scientists, Tatlock was under constant surveillance from J. Edgar Hoover's FBI. Her phones were tapped, and even her private life with Oppenheimer was under constant monitoring. FBI agents were spying outside when the two first met. Therefore, Hoover was among the first to learn of her death. Though some have speculated that she was extrajudicially assassinated, there has been no hard evidence to support such a claim.

Tatlock's life was complex, and that complication extended to her relationship with Robert Oppenheimer. Now her story will be told, at least in part, with all the scale of IMAX cameras in Christopher Nolan's upcoming "Oppenheimer."

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).