The Best Movies Turning 75 In 2021

The 1940s were a remarkable decade for movies. It began, of course, with World War II, which dominated the cinematic landscape for most of the decade. With the Golden Age of Hollywood in full swing, and countries all over the world releasing challenging and exciting films, audiences were hungry for some escapism to help them deal with the difficulties of their lives during wartime.

The year 1946 marked some significant changes in cinema around the world. For one, the Cannes Film Festival was first held in '46, and in the wake of WWII, the festival decided to celebrate films from all over the world. They did this by having nine films share the festival's top prize. Many films at this time were certainly made with the end of the war in mind — practically every film on this list was made either in a distinctly post-war setting, or as some sort of response to post-war life.

As films released in 1946 turn 75 years old this year, we wanted to take a moment to celebrate some of the most exciting films from 1946. Some were enormous successes at the time, some have been referenced over and over and over again, and many continue to inspire filmmakers 75 years later.

It's a Wonderful Life

Often considered the greatest Christmas movie of all time, Frank Capra's "It's a Wonderful Life" carries the trauma of war with it. It tells the story of George Bailey (James Stewart), a man devoted to helping those around him at the expense of his own happiness. His own misery leads him to contemplate suicide, but Angel Clarence Odbody (Henry Travers) intervenes and shows Bailey the importance of his life by allowing him to see how different the world would be if he had never been born.

One of the many reasons "It's a Wonderful Life" remains so timeless is its realistic approach to the characters. Sure, the story is about an angel with an ultimately uplifting message, but the film is unafraid to show darkness. For a family film, Capra's masterpiece doesn't back down from challenging issues like suicide, and in an unforgettable scene where George prays to God for help, we see the raw, unfiltered emotions of the brilliant Stewart.

This commitment to realism is also particularly evident in the treatment of Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore). Potter is rather relentless in his efforts to make Bailey's life miserable, and just as so many powerful people do, Potter gets away with it. The film's combination of fantasy and realism has ensured that it remains part of the culture for 75 years, most recently being referenced in 2021's "The Tomorrow War."

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Notorious

Alfred Hitchcock is one of the most renowned filmmakers in history, a director who certainly earned the moniker of the "Master of Suspense." Though perhaps best remembered for the films he would release between 1958 and 1960 ("North by Northwest," "Psycho," and "Vertigo,") one of the director's very best films, "Notorious," was released many years earlier in 1946. The film follows Alicia (Ingrid Bergman), who is enlisted by Devlin (Cary Grant) to spy for the U.S. and help take down a Nazi organization. Things become complicated when the pair begin to fall in love with each other, just as Alicia is instructed to seduce a Nazi industrialist (Claude Rains), a man who had previously been in love with her.

Hitchcock's "Notorious" is a tense, torrid romantic thriller whose technical aspects were every bit as ambitious as the story itself. Rains, Grant, and Bergman all deliver some of the very finest performances in their illustrious careers, and a sequence in a wine cellar is a firm reminder that Hitchcock's ability to elicit tension and suspense is unparalleled. It's Bergman's performance as Alicia that is especially memorable. As observed by film critic Angelica Jade Bastién for Criterion, "Bergman's face is a beautifully charged terrain forever subverting the dynamics we've come to expect of the bad girls of the forties: lips pursed on the edge of promise, eyes drinking in each detail, jaw tightening with fear or anger." Few films balance romance and fear better than "Notorious."

To Each His Own

Olivia de Havilland was one of the last living Hollywood Golden Age icons, passing away in 2020 at the age of 104. She left behind an extraordinary legacy, winning praise for her performances in films like "The Snake Pit," "Gone with the Wind," and "The Heiress," for which she won her second Academy Award for Best Actress. Her first win came a few years prior, for her work as Jody Norris in 1946's "To Each His Own."

The film, directed by Mitchell Leisen (who also helmed classics like "Midnight" and "Remember the Dawn"), tells the story of de Havilland's Jody, an enormously successful businesswoman, who, when she was younger, was forced to give up her illegitimate newborn child to avoid a scandal. She concocts a scheme to adopt the child, but the plan backfires, and despite wanting to raise the child herself, Jody is forced to watch from afar as her son grows up.

The film charts Jody's rise to prominence as a businesswoman, as she moves from America to Europe to establish a thriving cosmetics company. "To Each His Own" is sentimental in all the best ways, and refreshingly direct in its depiction of single motherhood in the early 20th century. It's de Havilland who makes the film so special — her blend of vulnerability, strength, wit, and determination is perfectly balanced.

Paisan

The second in Roberto Rossellini's War Trilogy, "Paisan" is one of the key films of the Italian Neorealist movement. Marked by its commitment to a sort of realism, these films typically focus on stories about the poor and working-class, shot on location and often using non-professional actors. They deal directly with the implications of the Second World War, focusing on the tricky moral and economic conditions left in the wake of war in Italy. "Paisan," one of Martin Scorsese's favorite films, is a sensitive and sincere portrait of the war, as well as the difficulties that language barriers played in wartime.

"Paisan" unfolds over six episodes that occur during Italy's liberation at the end of the war, taking place all over the country. Each episode begins with a map and newsreel footage to acclimate viewers to specific areas of Italy, and Rossellini had a different writer scribe each of the six episodes, including legendary Italian director Federico Fellini. "Paisan" was initially set to be something of a celebration of the American liberation of Italy, Colin MacCabe writes for Criterion, but Rossellini decided to focus on something he deemed more important — a realistic view of Italian life between 1943 and 1944. "Paisan" works as a sincere and intriguing war film, but it's also a valuable historical document.

Beauty and the Beast

When you first think of "Beauty and the Beast," the thought likely conjures up images of singing and dancing flatware, thanks to the 1991 animated Disney film. Forty-five years before Disney released their famous version, poet and filmmaker Jean Cocteau wrote and directed "Beauty and the Beast," the first, and arguably best, cinematic adaptation of the classic fairy tale. Though it lacks the musical numbers of the beloved Disney version, it makes up for it with brilliant performances, a haunting musical score by George Auric, and some of the best visual effects in the history of cinema (just watch the scene of Belle entering the castle).

Cocteau's career as a poet serves him beautifully in making "Beauty and the Beast," as the film has a tremendous elegance and flow to it. The set design and costumes are the stuff fairytale dreams are made of, and the beautiful black-and-white cinematography still feels new and fresh. The film received considerable acclaim, with film critics like Roger Ebert acknowledging "Beauty and the Beast" as "one of the most magical of all films ... here is a fantasy alive with trick shots and astonishing effects." Though some of the plot is similar to the Disney version, Cocteau's film strikes a very different tone, filling it with frightening imagery and a Freudian subtext. This is the classic fairytale at its best: beautiful, erotic, and utterly fantastical.

The Killers

Director Robert Siodmak garnered a reputation as a specialist of the film noir genre with 1944's "Phantom Lady." Two years later, he directed "The Killers," starring Ava Gardner and Burt Lancaster (in his debut). It would earn Siodmak his one and only Oscar nomination for Best Director, despite directing over 50 films. The film uses flashbacks to establish a non-linear timeline as it investigates a series of crimes that stem from the discovery of a dead man with a life insurance policy, twisting and turning to its thrilling conclusion.

On initial release, New York Times critic Bosley Crowther was keen to point out the great performances: "Burt Lancaster, gives a lanky and wistful imitation of a nice guy who's wooed to his ruin. And Ava Gardner is sultry and sardonic as the lady who crosses him up." Hemingway was famously not a fan of film adaptations of his stories, but Siodmak's "The Killers" was a definite exception and one of the few the author openly praised, as reported by AV Club – perhaps because only the opening minutes of "The Killers" are a faithful adaptation, while the rest is original. The film's impact can still be felt today, and has even appeared in Marvel's "Jessica Jones."

Till the End of Time

As World War II still loomed over America, some filmmakers turned to stories about the post-war experience, particularly from the perspectives of the soldiers themselves. Released a few months before the more acclaimed "The Best Years of Our Lives," Edward Dmytryk's "Till the End of Time" is a fascinating look at three Marines facing difficulties readjusting to post-war living.

The film's focus is largely on Cliff (Guy Madison), a former college student who enlists after Pearl Harbor. There's also his friend Bill (Robert Mitchum), a cowboy who has a silver plate implanted after being wounded in Iwo Jima, and Perry (Bill Williams), a former boxer who has become a double amputee, struggling greatly to use his prosthetic legs. While all three of their stories are interesting, thanks to an incisive and bracingly unsentimental script from Allen Rivkin, what makes "Till the End of Time" really stand out is Pat (Dorothy McGuire), a widow who loses her husband in the war, and fills the void in her life by sleeping around.

It would be so easy, particularly in the 1940s, to demonize Pat, but the script boldly treats Pat like a complex human being. McGuire delivers an excellent performance as she plays somewhat against type, showcasing a woman who is understanding yet distant and hard to read. Despite being overshadowed by "Best Years," Dmytryk's film is certainly worth seeking out.

The Big Sleep

Detective Philip Marlowe has had quite an illustrious career in Hollywood. The fictional character, first appearing in Raymond Chandler's novel "The Big Sleep" in 1939, has appeared in ten films and has been played by actors such as Robert Montgomery, George Sanders, James Garner, Elliot Gould, and Robert Mitchum. But it was Humphrey Bogart, who rose to superstardom after "Casablanca" in 1942, whose portrayal of Marlowe in 1946's "The Big Sleep" really put the character on the map.

The film was directed by Howard Hawks, a director with a remarkable ability to tackle virtually any genre, be it screwball comedy ("Bringing Up Baby'), westerns ("Rio Bravo"), musicals ("Gentlemen Prefer Blondes"), and sci-fi horror ("The Thing"). With "The Big Sleep," Hawks directed a pitch-perfect noir. Marlowe is sent to the luxurious mansion of the Sternwood family to help resolve gambling debts. As Marlowe leaves, he's stopped by Sternwood's daughter Vivian Rutledge (Lauren Bacall), who asks him to investigate a missing person. In the grand tradition of film noir, Marlowe gets far more than he bargained for, uncovering blackmail, murder, and a potential romance all while on the case.

The chemistry between Bogart and Bacall is positively scintillating, which is no surprise, as the two were married not long after filming "The Big Sleep." The two share one of the all-time great Hollywood romances, as Biography explores, with the pair staying together until Bogart's death in 1957. "The Big Sleep" is the second of five films they made together, and perhaps the greatest of them all.

A Matter of Life and Death

Peter Carter (David Niven) is flying a badly damaged Lancaster bomber during a combat mission over Germany. His parachute has been destroyed, and there is no chance of survival. In his last moments, he speaks with radio operator June (Kim Hunter). June gives Carter comfort in his final moments, before jumping out of the aircraft to his death.

Except, miraculously, Carter does not die. Conductor 71 (Marius Goring), the heavenly authority responsible for escorting Carter to the Other World, can't find him in the thick fog, leaving Carter perplexingly alive on Earth. As a result, Carter is sent to court, where he must appear in front of a jury in the Other World to plead his case for the right to live. Directed by British duo Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, "A Matter of Life and Death" unfolds largely in striking, ethereal technicolor, and in fact, is the only film on this list that isn't entirely in black-and-white.

The film is a heartwarming and insightful testament to the human spirit and has received considerable critical acclaim over the years, placing 20th on the British Film Institute's list of the greatest British films of all time. The film's influence has not waned over the years, even recently inspiring the ending of a certain Marvel film.

Gilda

If words could kill, Gilda (Rita Hayworth) would murder them all. In the now-legendary scene, casino owner Ballin Mundson (George Macready) asks his wife "Gilda, are you decent?" With a glorious flip of her hair and a glowing smile, Gilda responds, "Me?" She sees Johnny Farrell (Glenn Ford) next to Mundson, which turns her beaming grin into a sultry, seductive glare, as she places her gown strap back over her shoulder, continuing "sure, I'm decent." It's one of cinema's great introductions, and perfectly encapsulates Gilda's ability with men. There's no doubt she's about to become one of cinema's great femme fatales, a seductive woman certain to cause serious issues for anybody attracted to her.

Charles Vidor's "Gilda" is a sleek, sexy noir with sensuality pouring out of every frame. Though the cast is impressive throughout, Hayworth positively devours everyone else around her. Her divine yet devilish persona shines through this battle-of-the-sexes, arresting audiences with her striptease song-and-dance performance of "Put the Blame on Mame." Hayworth's performance is one of the greats in cinema history, and has influenced films as recently as "Mulholland Drive."

The Stranger

Orson Welles is most famous for his 1941 film "Citizen Kane," regarded by the British Film Institute as one of the greatest ever made. Made five years after "Citizen Kane," "The Stranger" is another 1946 film about life after the war. Mr. Wilson (Edward G. Robinson), an agent of the U.N.'s War Crimes Commission, is tasked with finding and capturing Nazi mastermind Franz Kindler (Orson Welles), who has taken up a new identity and erased all evidence of his existence. The only clue Wilson has to go on is the fact that Kindler has an obsession with clocks.

"The Stranger" is an exciting noir chock-full of great dialogue (Victor Trivas' writing was nominated for an Oscar), and Welles puts in double duty with a spine-chilling performance as Nazi Kindler while also showing his exemplary vision as a director. A thrilling climactic scene in — you guessed it, a clock tower — is a showcase of what made Welles so special in front of and behind the camera.

Shoeshine

Before making "The Bicycle Thief," a film that topped the inaugural Sight & Sound poll as the greatest film of all time, Italian director Vittoria De Sica directed "Shoeshine," an intimate story steeped in Italian neorealism about two boys, Giuseppe (Rinaldo Smordoni) and Pasquale (Franco Interlenghi), who shine shoes in the city of Rome. They strive to one day make enough money to buy a horse, but when they get tricked into a scheme by Giuseppe's older brother, it ends up putting their dream, and their lives, in danger.

While many films on this list are big-budget studio affairs, "Shoeshine" shows life on a very small scale of childhood friendship. While the film is a stark look at the difficulties of growing up poor in Rome, its themes of childhood friendship are undeniably universal. Orson Welles was a massive fan of the film, with Pauline Kael quoting him as saying, "what De Sica can do, I can't do. I ran his "Shoeshine" recently and the camera disappeared, the screen disappeared; it was just life."

Though De Sica's film is certainly informed by neorealism, it still has cinematic flourishes, and he does great work to bring screenwriter Cesare Zavattini's words to life. De Sica and Zavattini had an incredibly fruitful working relationship, collaborating on 26 films including "Umberto D.," "Miracle in Milan," and "The Bicycle Thief."

My Darling Clementine

Few directors are more synonymous with a particular genre than John Ford and westerns. One of the great American mythmakers, Ford is the man who gave us "Stagecoach," "The Searchers," "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance," and well over 100 other films, spanning an unfathomable seven decades. Ford has won four Academy Awards for Best Director, a number that no other person has matched. One of his best, if underappreciated, films, "My Darling Clementine," tells the story of the infamous gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

In "My Darling Clementine," Henry Fonda stars as Wyatt Earp, a laconic lawman determined to clean up the trouble-filled town of Tombstone, Arizona. Begrudgingly alongside Earp is Doc Holliday, with a boozy, bravura, career-defining performance from Victor Mature. Typical of many Ford films, the film features astonishing landscapes, showcasing the mystical glory of Monument Valley with fabulous location shooting. "My Darling Clementine" is considered something of an "anti-western" by Criterion essayist David Jenkins, thanks to its delightfully lazy pacing (after all, one of the film's most iconic images is Henry Fonda leaning back in his chair) and its general lack of violence. Still, the film simply exudes cool, and its remarkable use of space and thrilling performances have allowed it to stand the test of time.

La Otra

Dolores del Río stars in Mexican thriller "La Otra" in a double role as María Méndez, and her sister Magdalena. María is struggling through life as a humble manicurist, but at a Christmas party, she learns that her twin sister Magdalena has a lavish lifestyle. So María sets out to do what all sisters would do: kill her sister and assume her identity. Unfortunately for María, matters are about to complicate immeasurably when she discovers that Magdalena has a boyfriend, the slimy Fernando (Víctor Jungo). But wait, there's more — there's also Roberto (Agustín Irusta), deeply in love with the presumed-dead María.

"La Otra" is a terrific showcase for del Río, an exemplary actress who returned to Mexico after her career began to wane in Hollywood, as Vanity Fair claims. Playing two distinctly different roles gives del Río an opportunity to showcase a remarkable range of emotions that one character couldn't allow, and it's a stark reminder of what a shame it was that Hollywood couldn't make use of her gifts. Thankfully, del Río had a successful career in Mexico, and helped usher in a golden age of Mexican cinema.

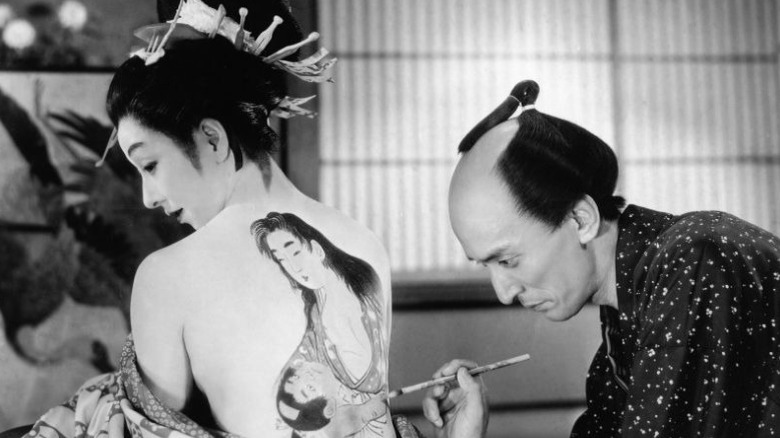

Utamaro and his Five Women

Japanese director Kenji Mizoguchi made plenty of films before gaining serious international attention with "The Life of Oharu" in 1952 and "Ugetsu" in 1953. Beneath the shadows of Mizoguchi's rapturously acclaimed later films is 1946's "Utamaro and His Five Women," a story of the life of Edo-era artist Kitagawa Utamaro and five of the women that played a romantic role in his life. The film was made during the Allied occupation of Japan, at a time when period films were rarely approved by occupation censors for fear of stoking nationalistic values, as writer Freda Freiberg explains. To bypass this, Mizoguchi had to ensure that there would be no swordplay in the film, and that it wouldn't feature a military occupation.

The film has signatures of Mizoguchi, including striking, languid long takes that allow audiences to become enraptured by the film's world. Utamaro as an artist was renowned for his bijin-e, or portraits of beauties, so unsurprisingly the film is filled with sumptuous imagery and the beautiful women that would have inspired his paintings. The film is a sight to behold and an exciting reminder of the great things to come for the now celebrated Japanese director.

Panique

Monsieur Hire (Michel Simon) is something of an eccentric — he keeps to himself, and nobody quite understands why he wants bloody cuts of meat or wears a camera around his neck all the time. Hire finds himself intrigued by Alice (Viviane Romance), a woman who's newly arrived in town, but things rapidly go awry when a woman is found dead in their quiet suburb, and suspicions about Hire's involvement rise to a boiling point.

Directed by Julien Duvivier, "Panique" is an entertaining noir, the dark themes of the film beautifully clashing with its carnival setting, complete with jaunty theme tunes breaking through the dense shadows. The film functions as a character study, with both Simon and Romance in great form, delivering nuanced performances. "Panique" is also a damning indictment of mob mentality, particularly the dangers of misinformation, and how easily it can spread into panic and hysteria. The film is unafraid to examine the very worst parts of human instincts. It's especially interesting when you consider Duvivier's personal history outlined by James Quandt for Criterion — he left France during World War II to work in Hollywood, and his first film upon returning was a not-so-thinly veiled critique of France's response to the war. With that in mind, "Panique" becomes even more fascinating.

Cluny Brown

Ernst Lubitsch began his career directing silent films in Germany, before moving to America to continue his remarkable success, transitioning from silent to sound films with relative ease. He had such a special approach to filmmaking that the phrase "the Lubitsch touch" was coined, noting his remarkable ability to take serious subjects and embolden them with elegance and wit. Celebrated director Billy Wilder was a huge fan of Lubitsch and attempted to explain the magic of the Lubitsch touch at the American Film Institute. One of Lubitsch's finest comedies, "Cluny Brown," is marked by its stunning sense of optimism and quirky sensibilities, which were greatly desired by postwar audiences.

Jennifer Jones stars as the titular character, a glorious free spirit with a penchant for breaking boundaries and trying new things, including a genuine love of plumbing. Her uncle (and guardian) is insistent that she learn her place in the world, and to that end, he sends her away to work as a parlor maid. It's in this very job she meets Andrew Belinski (Charles Boyer), a Czech refugee and famed anti-Nazi writer. Belinski is deeply appreciative of Brown's outlook on life, and the two strike up an unlikely friendship, though this is complicated by Brown's potential engagement to dull-as-dishwater Jonathan Wilson (Richard Haydn). With a fantastic lead performance from Jones, "Cluny Brown" is a radiant breath of fresh air and a delightful comedy for the ages.

The Best Years of Our Lives

Talk about saving the best for last! Filmmaker extraordinaire William Wyler delivered the most successful film at the box office of the entire decade with "The Best Years of Our Lives." The film tells the story of three veterans returning from World War II, and on top of its enormous financial success, the film also dominated the Academy Awards, winning eight Oscars, including best director, best actor, and best picture.

It examines the post-war lives of Air Force bombardier Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), Navy petty officer Homer Parrish (Harold Russell), and Army Sergeant Al Stephenson (Frederic March), as well as their respective families. While both Andrews and March were professional actors, Wyler strived for unmatched authenticity, and cast Canadian-born veteran Russell — who lost both of his hands in an Army demolitions accident — as Parrish. The bold move paid off better than anyone could have imagined, as Russell became the first non-professional actor to win an acting Oscar, and the only person ever to win two Oscars for the same performance.

What's so incredibly special about "Best Years of Our Lives" is how it continues to resonate with audiences, even 75 years after its initial release. Few films rival its sense of humanity, and it wastes not a single second of its epic 172-minute run-time. It's an authentic portrayal of the impact of war on both veterans and civilians alike, and it's no wonder that "Best Years of Our Lives" is one of the most commercially and critically successful films ever made.