Hitchcock Movies All Film Fans Need To Watch

The late director Alfred Hitchcock was born in 1899, and throughout a storied directing career from his first film, 1925's "The Pleasure Garden," to his last, 1976's "Family Plot," added several tropes to cinematic language and made an indelible mark on filmmaking as The Master of Suspense.

Hitchcock was prolific. He directed 53 feature films in addition to shorts and television projects, not to mention the films he worked on but didn't direct. He popularized the MacGuffin, is said to have "invented modern horror," and is synonymous with directors making cameos in their own films, though he didn't appear in all his films. There's even "the Hitchcock Touch" — that element in each film that makes it undeniably his, whether it's an icy blonde, a specific visual, or a particular theme. His cinematic world is one where no one is wholly innocent, even those accused of crimes they didn't commit.

With such an extensive oeuvre, Hitchcock's work may seem daunting for a film fan to tackle, but we're here to help guide through it. Below is a list of Hitchcock's movies all film fans need to watch, a primer of sorts taking you from his early silent films to his last feature film and points in between.

The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927)

Arguably the most important of his silent films, "The Lodger: A Story of The London Fog" is one Hitchcock himself called "the first true 'Hitchcock movie'" in an interview with director François Truffaut, one of the co-founders of the French New Wave. The interview is contained in Truffaut's book, "Hitchcock."

The film is based on a novel, "The Lodger," by Marie Belloc Lowndes, which was turned into a play called "Who Is He?" that Hitchcock saw. Matinee idol Ivor Novello plays the title character, a secretive man who is believed to be "The Avenger," a Jack the Ripper-like killer murdering blonde women in London. He falls under suspicion due to his obsessively private behavior, which is actually just a response to a deeply personal tragedy. Novello fit Hitchcock's "touch" of using well-known actors to portray innocents accused of dastardly crimes, both to engender audience sympathy and to play against type.

Although Hitchcock was held up as an example of an auteur by Truffaut, his work was often more collaborative than the term implies. Novello would go on to write and star in Hitchcock's next film, "Downhill" (1927), and Hitchcock's wife, Alma Reville, was Assistant Director and would continue to be an important part of his filmmaking process. "The Lodger" is worth watching for its atmospheric visuals and its codifying of themes Hitchcock would return to over and over. Plus, it's the film that got Hitchcock noticed in British cinema.

The 39 Steps (1935)

"The 39 Steps" is the second film in Hitchcock's "thriller sextet," made when he moved from British International Pictures to Gaumont British. Back then, directors and stars were usually part of the studio system, and Hitchcock was no different. "The 39 Steps" stars Robert Donat as Richard Hannay, an everyman type who gets caught up in espionage through no fault of his own. The theme of the ordinary citizen in dire straits without knowing why is another thread that runs throughout Hitchcock's career.

Hannay is drawn into a conspiracy while attending a show of Mr. Memory, a man with miraculous powers of recall. A shot rings out, a woman collapses into his arms, and he's roped in to trying to discover what "the 39 steps" are. No one who he talks to will believe he is not part of the conspiracy, and he is forced to go on the run for his life.

Hitchcock masters the spy thriller in what is also known as his "golden period" of British sound film. He bases his film on John Buchan's 1915 novel of the same name. He also employs the "double chase" structure — Hannay is chasing down those who did him wrong to clear his name, just as the spies and the police are chasing him for what he knows or what they think he knows. The double chase is another Hitchcock touch used to build and sustain suspense as he perfects his craft, making "The 39 Steps" quite, well, thrilling.

Sabotage (1936)

The next film in Hitchcock's "thriller sextet" to watch is "Sabotage," based on a 1907 novel by Joseph Conrad called "The Secret Agent." Charles Bennett, who also did the screenplay for "The 39 Steps," is credited with the script, though Hitchcock and his wife, Alma Reville, came up with the story idea prior to doing a treatment, a process he followed throughout his career.

In "Sabotage," Oscar Homolka plays Karl Verloc, who appears to be a mild-mannered theater owner but is really part of a group of terrorists. His wife, played by Sylvia Sidney, doesn't know. Scotland Yard, however, is suspicious of him, and John Loder's Detective Spencer goes undercover, getting close to Mrs. Verloc and falling for her once he realizes she is innocent.

The film was released as "The Woman Alone" in the United States, and a great deal of the story is about Mrs. Verloc's reaction to the tragedies that occur as a result of her husband's secret. More importantly, it plays with Hitchcock's notions of innocence. Verloc is guilty of many things, including the death of Mrs. Verloc's young brother. While Verloc goes on to pay for his crimes, her act of violence in reaction to what her husband's done is seen as justified, as she gets away with literal murder. Despite Hitchcock's own issues with his film — notably having to settle for Loder when Donat was unavailable — the movie is a classic.

Rebecca (1940)

"Rebecca" is the first film Hitchcock did in the American studio system. It garnered him a nomination for Best Director at the Academy Awards; while he didn't win, "Rebecca" did (for Best Picture). It's the start of Hitchcock working at Selznick International Pictures, which would prove quite fruitful for a time.

"Rebecca" is based on Daphne du Maurier's 1938 Gothic romance, also called "Rebecca." In it, a naive young woman (Joan Fontaine) becomes the second wife of Maxim de Winter, played by Laurence Olivier. Unlike Hitchcock's earlier, looser book adaptations, "Rebecca" is faithful to the novel, partly because of Hitchcock's own respect for the material, but also because producer David O. Selznick wanted it that way.

Maxim is a widower when he meets the young woman, who is only referred to as Mrs. de Winter. Once he brings her to his estate, Manderley, she soon learns she is living under the "ghost" of the first Mrs. de Winter, Rebecca, and is tormented by the housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson). Hitchcock was forced to make one major change in the story regarding Rebecca's death because of the Hays Code, but otherwise, the film maintains a great deal of the tone and actions in its source. It's also a great example of Hitchcock's ability to make something his own even as he stays within the strictures imposed upon him.

Lifeboat (1944)

"Lifeboat" was a self-imposed challenge for Hitchcock, as he wanted to see what would happen when filming on a limited set. The tale of a diverse group, trapped together in a lifeboat because their freighter is sunk by a German U-boat during World War II, is psychologically tense and maybe a tad moralistic. As Hitchcock later told Truffaut, the screenplay treatment was written by author John Steinbeck at Hitchcock's request, and was made at 20th Century Fox.

The film has no score and takes place entirely in the boat as the group tries to survive. Connie Porter (Tallulah Bankhead), a journalist, is the first person in the boat. She is eventually joined by several other characters, including Gus (William Bendix) and Joe (Canada Lee). One of the lifeboat's occupants, Willi (Walter Slezak), is German and turns out to be the captain of the U-boat.

The challenges for Hitchcock included framing the shots. He told Truffaut in their series of interviews that he "wanted to prove a theory" about the visuals of the prevailing psychological pictures of the time, which involved a lot of close-ups. What he created was a compelling character study that, though it was not well-received critically when it was released, has since been re-evaluated. This unusual movie is worth watching to establish that even with a limited palette and a confined setting (which he later repeated with the better-known "Rope"), Hitchcock was in full command of his art.

Strangers on a Train (1951)

"Strangers on a Train," a film noir mixed with the psychological thriller, is considered the start of Hitchcock's "peak years" as a filmmaker. Based on Patricia Highsmith's 1950 novel of the same title, "Strangers on a Train" arrives after Hitchcock had two box-office flops. Yes, even a master can falter!

His previous films (including 1948's experimental "Rope," which you should definitely put on your to-watch list) were in Technicolor, but Hitchcock returned to black and white here. "Strangers on a Train" begins when Guy Haines (Farley Granger), a tennis player in an unhappy marriage, meets Bruno Antony (Robert Walker), a psychopath who hates his father. Bruno proposes they do each other a favor by murdering the people in their lives who make them miserable. Because they are complete strangers, no one will ever figure it out. Guy thinks it's a sick joke, but when Guy's wife, Miriam, is murdered and Bruno demands Guy hold up his end of the bargain, Guy knows he is in trouble.

Hitchcock came up with some demonically good shots in this film, including the reflection of Bruno murdering Miriam in Miriam's dropped glasses. The scene with the carousel is also outstanding in its compositions and movement. Hitchcock additionally changed some elements of the novel to better fit his own pet themes, including keeping Guy innocent of murder so that he can be exonerated at the end of his suffering, whereas in the novel, he kills Bruno's father.

Dial M for Murder (1954)

Even the Master of Suspense succumbed to the 1950s fad that was 3D. What sets Hitchcock's "Dial M for Murder" apart from the other 3D films of the era was the relative lack of gimmicky items coming out at the audience. Instead, Hitchcock used the medium to create a depth of field that makes the film look more like the play it was based on.

Grace Kelly stars as Margo, who is married to Tony (Ray Milland). Tony knows Margot, who is the wealthy one in the marriage, cheated on him, so he decides to kill her for her money. He sets in motion a complex plan that involves blackmail, surveillance, and murder-for-hire to get rid of Margot, but it goes haywire when Margot kills her would-be murderer in self-defense. Tony saves his plan by making her look guilty of premeditation, and she is convicted and sentenced to die. Unfortunately for Tony, Margot's lover is a crime novelist who realizes something about Tony's story is not right.

The 3D version of the film did not do well with audiences, prompting exhibitors to beg to show the "flat" version instead, where the film did much better. Hitchcock does use some camera tricks to take advantage of the 3D, but does not rely on them, instead focusing on what will serve the story over what could — and did — go out of fashion.

Rear Window (1954)

In Hitchcock's first film at Paramount, "Rear Window," he again used Technicolor to excellent effect. "Rear Window," considered one of Hitchcock's masterpieces by film critics, stars James Stewart — the only other actor besides Cary Grant to be in four Hitchcock films — as L.B. "Jeff" Jefferies, a professional photographer cooped up in his Manhattan apartment with a broken leg. His girlfriend, Lisa, played by Grace Kelly, checks in on him, as does his nurse (an underappreciated Thelma Ritter).

To pass the time, Jeff uses his high-powered camera lenses and binoculars to spy on his neighbors across the courtyard, giving them nicknames and speculating with Lisa on their lives. While alone one night, he hears a scream and becomes convinced that Lars Thorwald, played by Raymond Burr, has murdered his wife. Lisa eventually believes Jeff and tries to help prove his theory, despite it putting her in great peril.

Hitchcock explores the psychological theme of voyeurism through Jeff's snooping. Because the entire story unfolds from Jeff's point of view, the audience is implicated in his gaze, a theory that has spawned countless academic articles and undergraduate essays. Hitchcock also deftly juxtaposes Jeff's stagnant helplessness with Lisa's burgeoning adventurousness, a sly bit of gender-role swapping in a more restrictive time. Kelly is flawless as the glamorous Lisa, while Stewart's Everyman persona fits Jeff perfectly. Hitchcock excelled at typecasting, believing that an audience with preconceived ideas of the actors aided characterization.

Vertigo (1958)

"Vertigo," another film in Hitchcock's peak years, is a psychological thriller starring James Stewart as retired detective John "Scottie" Ferguson, who suffers from both acrophobia and vertigo. The film deals with the theme of obsession — in this case, Scottie's obsession with certain women.

After a tragic event in Scottie's life, a man named Gavin, played by Tom Helmore, hires Scottie to tail his wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak). Gavin claims Madeleine is mentally fragile and needs Scottie to watch her. Scottie becomes infatuated with the tormented Madeleine, who eventually takes her own life. Scottie soon has a breakdown, not knowing what's real and what's not. When a woman named Judy who looks an awful lot like Madeleine appears, it furthers Scottie's obsession and he tries to change her into a copy of Madeleine. Is Scottie insane? Or is Judy really Madeleine, and there's a conspiracy afoot?

Apart from Hitchcock's use of the dolly zoom (how he gets that "vertigo" effect) and camera shots such as high angles to produce specific reactions, he also had other techniques he used on audiences, as he told Mike Scott in a famous 1966 interview. These include manipulating the audience's emotions, letting the audience have more information than the characters, using everyman characters for better audience identification, using locations as part of the story, and providing suspense throughout. While these may seem typical now, Hitchcock carefully combined them in masterworks such as "Vertigo" to keep you glued to your seat.

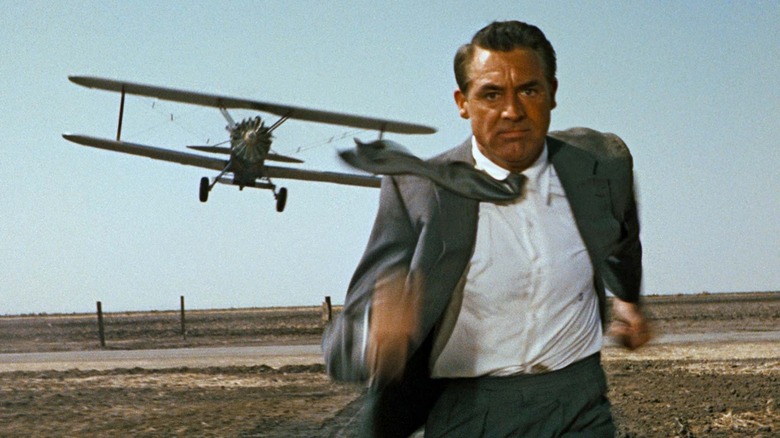

North by Northwest (1959)

"North by Northwest" was a one-off production for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer that Hitchcock made while still working at Paramount. The movie is filmed in VistaVision, a type of widescreen format he used on "Vertigo" (as well as "To Catch a Thief" (1955), "The Trouble with Harry" (1955), and "The Man Who Knew Too Much" (1956)). Paramount developed VistaVision to compete with CinemaScope, and Hitchcock took full advantage of its bigger visual canvas.

Another spy thriller, "North by Northwest" continues Hitchcock's use of the Everyman stereotype, though Cary Grant's Roger Thornhill is a little suaver than the average guy. Thornhill is kidnapped by spies in a case of mistaken identity, and when they realize it, they try to kill him. He's then drawn into an intricate web of lies, falling for Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint), who may or may not be a devious spy herself. The ever-watchable James Mason stars as enemy spy Phillip Vandamm.

Thornhill is not entirely "innocent" — there's a running joke that he does not return his mother's calls, making him a bad son. The film also has more humor than is usual in Hitchcock thrillers. Film fans will want to see it not only because it's entertaining as all get out, but because it has some of Hitchcock's most iconic visuals, including the scene of Thornhill being chased by agents in a crop duster and a chase that takes place on Mount Rushmore.

Psycho (1960)

In the middle of Hitchcock's Technicolor years, he chose to film "Psycho" in black and white. The starkness of the lighting and shadows adds to the horror that begins once Janet Leigh's Marion Crane gets to the infamous Bates Motel and gets the attention of Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) – and Norman's jealous mother.

"Psycho" is the start of Hitchcock's years with Universal Pictures. Considered a classic horror film, "Psycho" never actually shows Marion getting stabbed in the infamous shower scene. Through clever camera angles and editing, Hitchcock tricked audiences into thinking they saw Norman's knife go into Marion's body, but it never touches her. A breakdown of the scene on History notes that there were "78 camera set-ups and 52 edits," enough to convince a generation they'd seen something that was never shown.

One of the reasons for Hitchcock's ingenuity was the Hays Code, which restricted what could be shown on screen, including content. "Psycho" manages to be transgressive on a number of fronts, not just in the shower scene but in having Marion meeting her divorced lover, Sam (John Gavin), in a hotel room. The marketing for the film was elaborate, too, to get people away from their televisions and back into theaters, and included not allowing latecomers to enter the theater, courting the film's controversy, and asking people not to reveal the film's biggest shock. We're not saying Hitchcock invented "No spoilers," but ...

The Birds (1963)

"The Birds" is a classic of apocalyptic horror, with one of Hitchcock's more ambitious MacGuffins (the reason the birds begin attacking is never explained). The film is based on Daphne du Maurier's story "The Birds," although Hitchcock's interpretation is much looser than when he adapted "Rebecca." Special bird effects were done by legendary animator Ub Iwerks.

Tippi Hedren, one of Hitchcock's "icy blondes," stars as Melanie Daniels, a socialite in the news for frivolous acts. She meets Mitch (Rod Taylor), who's in town to buy lovebirds for his young sister, Cathy, played by Veronica Cartwright. Melanie winds up bringing the birds to Mitch's house in Bodega Bay, where she meets his ex-girlfriend, Annie (Suzanne Pleshette), and his domineering mother, Lydia (Jessica Tandy). The attacks by the birds are easy to dismiss at first as strange accidents, but when they begin assaulting the townspeople en masse, Melanie is blamed by the hysterical, insular residents.

Hitchcock would solidify his horror bona fides with "The Birds." Especially masterful in terms of generating dread is the scene with the crows quietly gathering on the jungle gym outside the schoolhouse and behind Melanie, who's waiting for Cathy. Watching the kids, Melanie, and Annie try to walk past the crows without riling them up is almost unbearably tense. Couple that with the noise the birds make courtesy of composer Bernard Herrmann, who also composed the famous score from "Psycho," and you have avian terror that has yet to be equaled.

Torn Curtain (1966)

While "Torn Curtain" was not as critically well-received as Hitchcock's past films, it's still worth a watch for film fans to see how Hitchcock handled working with two actors he didn't exactly want in a story that wound up being a more generic spy thriller than he'd made in the past.

In "Torn Curtain," Paul Newman plays Michael Armstrong, a rocket scientist who appears to defect to East Germany. Julie Andrews plays his fiancée/assistant, Sarah Sherman, who is caught unaware by the defection. Things are not what they seem, of course, as it's revealed Michael is really undercover. It then becomes a matter of Michael and Sarah getting out of East Germany alive once Michael gets the information he's after.

Behind the scenes, Hitchcock was pressured to hire Newman and Andrews, who were both costly. Andrews commanded a large salary Hitchcock didn't want to pay now that he was producing — and thus, paying for — his own movies. As for Newman, his method acting rubbed Hitchcock the wrong way, and the two didn't get along.

Still, "Torn Curtain" has the famously long, somewhat sickening scene showing just how hard it is to kill someone. Also, according to Ken Mogg in "The Alfred Hitchcock Story," the "Gamma Five" anti-missile project in the film is the director's "most prescient MacGuffin," as it "anticipated by more than a decade President Reagan's 'Star Wars' project."

Family Plot (1976)

Hitchcock's final film, "Family Plot," is a macabre comedy with a pun for a title. It was a bigger hit with critics than with audiences, something that seemingly depressed Hitchcock, according to Truffaut's book.

In "Family Plot," Barbara Harris and Bruce Dern play grifters Blanche and George. She pretends to be psychic based on information he gleans from potential marks he drives in his taxi. A wealthy woman winds up hiring the pair to find the heir to her vast fortune. Meanwhile, Arthur (William Devane) is a successful jeweler who lives with his girlfriend, Fran (Karen Black). They also happen to kidnap rich people and ransom them for jewels. It turns out Arthur is the heir, and he's not especially pleased that someone's trying to find him. Murder and mayhem follow.

Though Hitchcock wanted to hire more marquee names, such as Jack Nicholson for George and Goldie Hawn for Blanche, he was happy with the actors he had, and not just because they cost less in salary. And though 1976 audiences may not have been as enthusiastic for "Family Plot" as 1960 audiences were for "Psycho," the former is worth watching to see the culmination of the great Master of Suspense's career.