The Most Misunderstood Movie Moments In History

Great cinematic works have scenes that stay with us forever, whether because they thrilled us, made us laugh, persuaded us to think in new ways, or helped us feel something we wouldn't have otherwise felt. Who will ever forget Indiana Jones running from that boulder, the destruction of the Death Star, Charlie Chaplin getting eaten by a machine in "Modern Times," or the shower scene in "Psycho"? Cinematic moments like these are iconic and influential, often inspiring new generations of creators.

At the same time, even the best films in cinema history sometimes have scenes that are commonly misunderstood. From actions with unclear implications to lines that are ambiguous, there are many films whose meaning in one spot or another has proven elusive. Indeed, some of our greatest filmmakers have masterful works with scenes that resist easy understanding–auteurs from Hitchcock to Scorsese and Spielberg to the Coppolas (both father and daughter) have all produced wonderful films with scenes whose meanings have stumped many an audience member. Here are some of the most misunderstood movie moments in history.

Vertigo's big twist isn't the point of the film

Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo" is arguably the most influential film in his long, jam-packed oeuvre. The thriller follows erstwhile cop John "Scotty" Ferguson (Jimmy Stewart), whose vertigo and fear of heights contributed to a workplace tragedy from which he's still recovering at the film's beginning. Retired from the force and now a private investigator, his old friend Gavin Elster hires him to tail Gavin's wife, Madeleine, out of supposed concern that she's in danger. Madeleine is fixated on a lookalike ancestor who died under grim circumstances, and Scotty is hired to get to the bottom of it. The truth, of course, is far stranger than it seems, and we discover that a woman named Judy Barton was impersonating the real "Madeleine" in an elaborate ruse to cover up a real murder. This sends Scotty into a spiral of obsession that ends, unsurprisingly, in a tragic fashion.

In its day, "Vertigo" was ill-received by a number of critics for its revelation of the ruse of Madeleine's true identity so early in the film (a decision that Hitchcock reportedly also wavered on). This shouldn't affect viewers' appreciation of the film, however. The big reveal about Madeleine's identity is irrelevant; what happens afterward is still fascinating to watch. "Vertigo" isn't primarily a story about murder and deception as much as it's about the consequences of obsession, and the reveal is important more for its effect on Scotty's psychological unraveling than for any other reason.

Taxi Driver's ending doesn't glorify Travis Bickle, it criticizes us

Martin Scorsese's masterful "Taxi Driver" follows Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), a lonely, socially stilted, insomniac cabbie whose isolation and disdain for the seediness of 1970s New York portends his eventual existential crisis. He attempts to start a relationship with campaign aide Betsy, but the downfall of that potential relationship further unhinges Travis and sends him on a misguided and increasingly extreme search for meaning. In this search, he turns to violence, at first planning to assassinate the political candidate Betsy worked for. When that mission fails, he then becomes obsessed with saving 12-year-old prostitute Iris (Jodie Foster) from her pimps. In the infamous end, we watch Travis survive to be celebrated as a hero, leading some to interpret the film's ending as glorifying Bickle's egregious behavior and damnable thoughts. This take has led some to criticize Scorsese for glorifying violent masculinity (while some even take the interpretation that Bickle dies).

While "Taxi Driver" puts the audience uncomfortably close to Travis Bickle, it's clear throughout the film that he's becoming increasingly brutal, menacing, chaotic, paranoid, and unprincipled (despite his love of trite, often self-contradictory aphorisms). That he is celebrated at the end for his violent act on Iris' behalf isn't Scorsese giving the metaphorical thumbs-up to Bickle's behavior. The public honored a bad or possibly severely ill man as a hero, and thus the film and its ending are more a criticism of society than they are a celebration of Bickle.

Total Recall's director has answered if the film and its ending are real or dreams

In "Total Recall," construction engineer Douglas Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) has strange dreams of Mars and a woman there in the year 2084. Despite warnings that it may be lobotomizing some patients, he visits a company called Rekall that controversially uses memory implants to simulate unique and fantastic vacations. He chooses the program "Blue Sky on Mars" and opts for an espionage element in his package. He wakes believing himself lost in a world of intrigue and conflict, with factions in hot pursuit as he tries to figure out what's real. The entire film hinges on a complex plot that's designed to leave it unclear whether he really is a secret agent or not.

In the film's ending, Quaid is on a Martian mountain and we see what looks like a bright flash right before the credits roll, the character still unsure if he's living a dream or reality. According to director Paul Verhoeven, however, it's all a dream. Quaid waking up to a world of espionage "is part of the dream... That's the trick of the company, that they make a dream that's so convincing that it seamlessly goes from the first reality into the second one." So all these moments of Martian adventures, down to the end? Dreams. In this interpretation of the film, that pseudo-optimistic flash of light may well be Quaid sitting in a chair and unknowingly receiving the lobotomy he was warned about.

The film version of Starship Troopers is satirical while the novel is not

"Starship Troopers," based on Robert A. Heinlein's novel, sees the human forces wage a dedicated war against an organized army of extraterrestrial insects, the "Bugs." The human forces are lead by the United Citizen Federation, in which citizenship is earned by serving the military in some capacity or other. They fight to defeat the Bugs at all costs. The whole film at face value is an over-the-top celebration of the military from the infamous classroom scenes to its many propaganda videos, including a notable moment discussing the "failure of democracy." It even posits that violence is "the supreme authority from which all other authorities are derived." These moments have led some to think the film endorses Heinlein's jingoism—and that's a misunderstanding.

Verhoeven's adaptation of "Starship Troopers" is intended to be a sendup of the military fetishization of the novel (hence its totally over-the-top nature). The filmmaker has repeatedly stated that the film was a satire of the novel and the fascistic elements of American society, going so far as to say, "of course, we really, really tried to get away from the novel, because we felt that the novel was fascistic and militaristic." In short, the film isn't intended to endorse the more dogmatic elements of Heinlein's novel, but to lampoon them (whether knowing this makes the movie more watchable or not is a question of personal taste).

Fight Club isn't celebrating attempts to find meaning through violent masculinity

David Fincher's "Fight Club," based on the Chuck Palahniuk novel of the same name, centers around Edward Norton's unnamed Narrator: a mild-mannered but unhappy and sleepless office drone who attends group therapy in an effort to feel literally anything. He meets the mysterious Marla there, as well as the dangerous Tyler Durden. The latter helps our Narrator on his quest to find feeling by introducing him to Fight Club, a clandestine meeting of disaffected men who reject society and express themselves through, well, fighting. A cesspool of angry masculinity ensues, building into something far more dangerous. One of its most notable moments involves Durden's speech to the fight club about how average Americans are "slaves with white collars" who lack purpose and can only find it in rejecting consumerism.

This moment and many others in the film are misunderstood as celebrations of violent masculinity, so much so that a wave of fight clubs actually sprang up from misguided men who didn't watch the film closely enough. It's revealed that the charismatic Tyler Durden and the milquetoast Narrator are one and the same; Durden is just his malignant alter ego. As in "Taxi Driver," Tyler's increasingly extreme actions aren't laudable rejections of the status quo. They're the unintended product of a troubled mind that's substituting dangerous behavior for materialism.

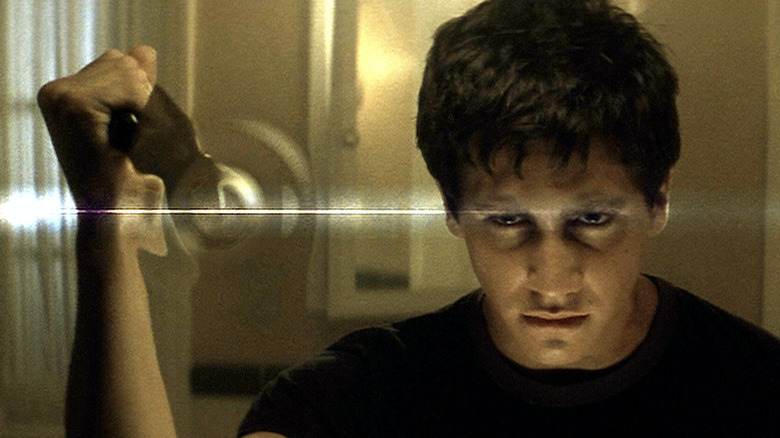

The end of Donnie Darko is about fixing unstable universes, not time loops

In "Donnie Darko," Donald J. "Donnie" Darko (Jake Gyllenhaal) is a smart teen with a problem that gets him into trouble: he sleepwalks. One night, he sleepwalks outside his home, meeting a strange figure in a hideous rabbit costume who delivers an ominous message about the end of the world 28 days later. When Donnie wakes up, he learns that a jet engine of unknown origin has crashed into his bedroom. Donnie continues to have visions of the rabbit and strange experiences as he comes closer and closer to that 28-day mark. The film appears to end with Donnie opening up a portal, causing the jet engine to fall back in time and kill Donnie in his sleep, saving reality by closing some sort of temporal loop.

In the film's supplemental material, it becomes clear what really happened. An unstable alternate universe opened up that was going to end and threatened the main universe, but Donnie was able to close the alternate universe and save the main universe... so it's really about closing unstable realities more than it's about temporal loops. (It doesn't help that Roberta Sparrow's book explaining all this is called "The Philosophy of Time Travel," but there you go.)

The beings at the end of A.I. Artificial Intelligence looks like aliens, but they're not

"A.I. Artificial Intelligence" is a film set in a post-climate change world, where the human population is diminished but technological advancements have created advanced robots. These creations (Mecha) are human in appearance, but fail to achieve the complex emotional capacities of humans. This changes with the invention of David, a prototype Mecha who is engineered to experience love. He joins a family whose own son, Martin, has a rare condition. Martin unexpectedly recovers, and his increasing antagonism towards David ultimately results in the latter's abandonment, and we follow David's adventures through the dregs of human and Mecha life.

David gets buried under the Coney Island Wonder Wheel and is recovered 2,000 years later. By that point, New York is buried under ice and humanity is long since extinct. The beings that free David are lanky, relatively featureless entities called the Specialists. While they resemble aliens, they're actually vastly advanced Mecha descendants. The film's end has nothing to do with alien explorers recovering David, and everything to do with how we've caused our own extinction and left a world fit only for artificial life.

The ending to Lost in Translation isn't as romantic as everyone assumes

Sofia Coppola's engaging "Lost in Translation" follows a movie star at the end of his era named Bob Harris when he meets newlywed Charlotte in Tokyo. They're both isolated in foreign territory, finding increasing solace in each others' company. The film chronicles that increasing relationship in its complexity, as unlikely as it is. The film ends right before Bob leaves Tokyo. He sees Charlotte on a crowded street, gets out, and embraces Charlotte. He whispers something in her ear that we can't hear and the two depart. It's often interpreted as a romantic moment, a mysterious, inaudible lover's dialogue before a tragic departure.

According to Coppola herself, however, "that thing Bill whispers to Scarlett was never intended to be anything. I was going to figure out later what to say and add it in and then we never did." Far from being a romantic gesture, it means... well, either nothing in particular or whatever you want it to.

(500) Days of Summer isn't a tragic romance at all

This time-jumping film follows the lovelorn Tom Hansen's (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) relationship with the charming Summer Finn (Zooey Deschanel). Tom fixates on Summer, whom he treats less as a person and more as an idea. Spoiler: He does not "get the girl" at the end, and instead she finds happiness with a different gentleman. Near the end, Tom and Summer meet again. After Tom painfully tries to understand why the relationship failed, he says, "You never wanted to be anyone's girlfriend but now you're somebody's wife... I don't think I'll ever understand that."

Many viewers walked away from this moment, and the film generally, thinking that Summer was a villain for breaking Tom's heart. But the film isn't really about the pain of a love that got away, as it's often misinterpreted. It's really about Tom's possessiveness over Summer and his inability to accept her making choices that don't benefit him.

In an interview, star Joseph Gordon-Levitt even said as much: "I would encourage anyone who has a crush on my character to watch it again and examine how selfish he is. He develops a mildly delusional obsession over a girl onto whom he projects all these fantasies." In that light, Tom's not really a romantic lead protagonist, and Summer isn't the passive object of his affections.

Inception's ending isn't even about whether the top spins or drops

One of the more stunning science fiction tales in recent memory, "Inception" has Dom Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) as elite corporate spies who use a complicated process called "extraction" to clandestinely discover deeply hidden secrets from targets' minds–for a hefty price. As a consequence of his efforts, Dom has been exiled from the United States (and, incidentally, his children), but a new client offers him a free and clear record in exchange for a dangerous job. "Extraction" involves entering a target's subconscious mind, sometimes multiple layers in, escaping the target's psychological defenses, and typically taking information–but this job involves a much deeper entry to plant an idea.

These jumps are dangerous, so Cobb has a spinning top that he uses to determine if he's still in the dream. If it falls, he's in reality. The film ends with Cobb spinning the top and walking away; we never see it drop. Fans have debated whether or not the top was going to fall and whether or not the ending is a dream or real. The real point, according to Christopher Nolan, is that Cobb walks away because he doesn't care about the top, he's walking towards his children.

Man of Steel's ending is the origin of his no-kill rule, not a betrayal of it

The Man of Steel is plagued by a series of great films that have deeply misunderstood (or understandably confounding and physics-defying) elements. Zack Snyder's "Man of Steel" follows Kal-El as he escapes a dying planet, arrives on Earth, grows up, and balances his secret human life as Clark Kent against the need for Superman. He's challenged when a group of genocidal Kryptonians arrive (led by General Zod) and cause havoc. Superman has no choice but to kill Zod. This caused a bit of fan fervor, with distraught viewers claiming that Superman would never kill and therefore the film's ending is a betrayal of the character. That interpretation is both incorrect and beside the point.

When Superman first debuted in 1939, he didn't have a rule to never kill his enemies. He rarely did so, but when lethal force was required, he'd use it. Since then, Superman has, when necessary, killed villains. The situation in "Man of Steel" definitely required intervention at any cost; letting Zod live would have resulted in the deaths of innocents. Most importantly, however, Superman's no-kill rule isn't the point. Zod is an early conflict for the godlike hero, so we're seeing the origin of his no-kill-unless-I-gotta principle.

Hulk wasn't afraid in Avengers: Infinity War

The various films in the first era of the Marvel Cinematic Universe had built up to one major threat: Thanos, the Mad Titan whose Infinity Stone quest results in The Blip that disappears half the population of the universe. This quest leads to an epic showdown in "Avengers: Infinity War," the first part of the series' two-part conclusion, that ends in Thanos' shocking success, leading to half the universe just... evaporating. Before that final moment, one chain of events that got fans guessing involved our favorite green rage monster, the Hulk.

Earlier, Hulk badly loses a fight to the Mad Titan and spends the rest of the film refusing to fight, leading fans to interpret the situation as the Hulk being afraid to fight Thanos after his unexpected loss. According to director Joe Russo, however, it isn't that at all: Hulk simply didn't want to keep fixing Banner's problems. Russo commented, "People have speculated whether there was some fear on the Hulk's part about having to face Thanos again... but I think ultimately what it is, is that he's tired of playing hero to Bruce Banner."