The Most Frightening Horror Movies Based On Short Stories

For every horror movie drawn whole, bloody, and original from a screenwriter or director's imagination, there's an equal number that are adapted from works of fiction. The list of horror films based on novels is long and noteworthy — everything from Frankenstein and Dracula to The Exorcist, The Silence of the Lambs and Bird Box – but there are also countless terror tales based on short stories. The works of Edgar Allan Poe, H.P. Lovecraft, and Stephen King alone have provided the foundations for dozens of horror titles, both good and bad, while "The Turn of the Screw" by Henry James and Richard Connell's "The Most Dangerous Game" alone have adaptations that approach the double digits.

Why do short stories have such appeal to horror filmmakers? Well, money, for one — the rights to a short story are usually less prohibitive than a novel. But there's also an urgency to the short story format. Writers only have so many pages before they need to show their scare cards, which requires a bigger, badder, and usually bloodier impact to land in the readers' consciousness. That kind of payoff appeals to horror-minded moviemakers and has led to some famously frightening genre efforts. The following are 11 of the most terrifying feature films that originally began as short, sharp, and scary stories.

Be forewarned: Some spoilers may also follow.

Freaks freaked out moviegoers in 1932

MGM's Freaks has shocked and amazed viewers since its release in 1932. The film, directed by Tod Browning (known for the 1931 Dracula with Bela Lugosi), features actual sideshow performers, many with striking and real physical disabilities, in a macabre Gothic story of love, betrayal, and revenge that has earned both widespread praise (it's been preserved by the National Film Registry) and condemnation (the film was banned in England for 30 years). Numerous writers, including uncredited future Oscar winner Charles MacArthur, worked on the script, which drew on American horror/mystery writer Tod Robbins' 1926 story "Spurs" for its premise.

Those who seek out the story, which has been anthologized numerous times, will find that very little connects the two projects beyond the carnival setting and an ill-fated love triangle between three performers — a little person, a beautiful bareback horse rider/trapeze artist (depending on the version), and her male partner. Horror fans may also be disappointed to find that the fate of the two "normal" characters in Robbins' story is somewhat less upsetting than what happens to trapeze artist Cleopatra and strongman Hercules in Browning's film.

The Fly: bugging moviegoers for over 60 years

One of the biggest screams in '50s science fiction and horror comes in 1958's The Fly, in which scientist Andre Delambre gets his genes crossed with a housefly's in his matter transportation device. Author James Clavell wrote the script for Kurt Neumann's film, but the idea itself came from the short story of the same name by French-British writer George Langelaan.

The story, which appeared in a 1957 issue of Playboy magazine, was adapted to film with very few changes. The primary differences: Langelaan's story takes place in France, while Neumann's film is set in Canada. Clavell also spared Delambre's wife, played in the film by Patricia Owens, from the downbeat fate suffered by the character in the story.

The story was also credited as the inspiration for two so-so sequels, Return of the Fly in 1959 and Curse of the Fly in 1965, as well as for David Cronenberg's 1986 remake. For this version, director and co-writer Cronenberg only needed the fly in the transport device to craft one of his most haunting experiences in body horror.

The Birds is one of Hitchcock's most frightening films

Three stories by British author Daphne du Maurier were adapted into film by Alfred Hitchcock – the novels Rebecca and Jamaica Inn and the 1952 short story "The Birds," which terrified audiences in 1963 (while also netting an Oscar nomination for special visual effects) and has made moviegoers nervous about their avian neighbors ever since. Du Maurier was inspired after seeing a farmer attacked by birds while plowing a field and retained that image for her story, which pitted a Cornish farmer against a growing army of enraged birds.

Screenwriter Evan Hunter — better known as crime fiction author Ed McBain — expanded greatly upon du Maurier's story by moving the action to the Bay Area, adding numerous characters as well as a tone that deliberately veered from humor and romance to abject terror over the course of the film. What both projects share is a lack of concrete reason for the birds to revolt: Du Maurier's story suggests that a change in weather is the motivation, while Hitchcock alluded in interviews that the attack was nature's revenge on man. But neither is ever confirmed, which makes the phenomena in both film and story all the more chilling.

Kwaidan: four Japanese ghost stories by an English-language writer

An Oscar nominee for Best Foreign Language Film in 1966, the 1965 Japanese supernatural anthology film Kwaidan draws inspiration for its four stories of ghosts and humans from the work of Lafcadio Hearn. A Greek-Irish writer who wrote extensively about Japanese culture and legends while living in that country during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Hearn's stories introduced Western readers to the vast array of ghosts and creatures that populated Japanese folklore. Four of those stories were adapted for Kwaidan, directed with stunning visual flair by arthouse favorite Masaki Kobayashi.

The scares here are milder than what modern fans have come to expect from J-horror – though the title of the third story, "Hoichi the Earless," should give you an idea of its petrifying payoff — but there's a strong connection between the onryō, or vengeful female spirits, in two stories ("The Black Hair" and "The Woman in the Snow") and the revenge-minded spirits in The Ring, the One Missed Call series, and countless other Japanese ghost movies.

The mystery of Black Sabbath's source material

Italian horror maestro Mario Bava's 1963 anthology film Black Sabbath attributes its three startling stories of supernatural horror to source material by three authors whose last names should be familiar to avid readers of 19th-century world fiction — de Maupassant, Chekhov, and Tolstoy.

Well, that's only partially true. The Tolstoy credited with the source material for "The Wurdulak," a story of Russian vampires, isn't War and Peace author Leo Tolstoy but his second cousin, Alexei Tolstoy, who was better known for his plays. And it's not Anton Chekhov who penned the inspiration for the supremely creepy "Drop of Water" but someone named Ivan Chekov, who actually isn't a real person at all but something of a joke by Bava and credited co-writers Alberto Bevilacqua and Marcello Fondato. As for Guy de Maupassant's involvement in "The Telephone," some historians suggest that this is again a fabrication — and, in fact, there's an additional credit for someone named "F.G. Snyder," who is also a made-up individual — though Bava historian Tim Lucas has suggested that the episode bears a passing resemblance to de Maupassant's story "The Horla," which was made into Diary of a Madman, starring Vincent Price and released the same year as Black Sabbath.

Regardless of real or imagined authors, Black Sabbath is one of Bava's most enjoyable and spine-chilling titles, thanks in no small part to Boris Karloff, who both narrates the film and brings the shivers to "The Wurdulak."

Horrors of Malformed Men and the Japanese Edgar Allan Poe

Chances are, you've never seen anything like the 1969 Japanese film Horrors of Malformed Men. It's a kind of mystery-horror hybrid, about an amnesiac who escapes from an asylum and assumes the identity of his exact double, then travels to a island where the double's father conducts strange experiments. But even that doesn't scratch the surface of Malformed, which also involves laboratory-made monsters, flying body parts, and bizarre set pieces that resemble performance art (the film's villain is played by experimental dance choreographer Tatsumi Hijikata).

Some of the film's bone-deep weirdness is the work of cult director Teruo Ishii, whose eclectic filmography includes everything from monster-fighting superhero action to softcore movies. But a lot of the odd and unsettling aspects can be linked to Japanese writer Edogawa Ranpo, whose strange and grotesque stories provided the inspiration for Ishii's script with Masahiro Kakefuda. Critical opinion varies on the exact sources, but two novels are most often cited, along with characters, elements and themes from various short stories. The pen name of author Taro Hirai (it's a play on "Edgar Allan Poe," one of his favorite writers), Ranpo wrote stories that straddled detective, pulp, and horror fiction, that often touch on subjects considered taboo in his day, including sexual identity, disfigurement, and obsession. As a result, Ranpo occasionally ran into trouble with censors –- as did Malformed, which was banned in Japan for its disturbing imagery.

Steven Spielberg got a career boost from Richard Matheson and Duel

Richard Matheson's name comes up countless times in the history of horror, fantasy, and science fiction in the 20th century. He's linked to some of those genres' most influential and popular films and television series, from Twilight Zone and I Am Legend to Star Trek and Somewhere in Time. Matheson is also responsible in part for helping to launch Steven Spielberg's film career with the 1971 TV movie Duel.

Matheson adapted his own short story, published in Playboy in 1971, for the ABC Movie of the Week. The script, about a motorist (played by Dennis Weaver) pursued by a faceless and relentless trucker, caught the attention of Spielberg, who earned huge ratings and widespread critical praise for his nail-biting mix of suspense and motorized action. So popular was Duel that it was released to theaters in international markets, which, in turn, helped to pave the way for Spielberg's motion picture career with The Sugarland Express in 1974 and then Jaws. He later paid tribute to the big break afforded by Duel by inserting the truck's monster-like roar into the finale of Jaws, when the shark's body sinks into the ocean.

Don't Look Now, but you're going to see something scary

Horror fans, critics, and filmmakers alike have cited cult filmmaker Nicolas Roeg's 1973 feature Don't Look Now as one of the best and most influential supernatural thrillers of the 1970s. Allan Scott — co-creator of The Queen's Gambit – and actor/writer Chris Bryant adapted the short story of the same name, written in 1971 by Hitchcock favorite Daphne du Maurier, for Roeg's film, which stars Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie as grieving parents who come to believe that their late daughter may be trying to warn them about an impending threat.

The script closely follows the source material's storyline, including its shocking final revelation and conclusion, and Roeg's unique editing and color schemes (red plays a important role in the film), have influenced countless creative figures. Among those who have paid homage to Don't Look Now, either in interviews or with their own films or television projects, are Ari Aster, David Cronenberg, and Joel Schumacher, whose 1990 film Flatliners features an overt reference to the tiny figure that haunts Sutherland and Christie in Roeg's film.

The transformation from Who Goes There to The Thing

All three film versions of The Thing – the 1951 black-and-white adaption, John Carpenter's grisly, groundbreaking take from 1982, and its 2011 prequel — owe their existence to John W. Campbell's novella Who Goes There? Published in 1938 in the magazine Astounding Science Fiction – for which Campbell served as editor — the novella details the battle between a research team in Antarctica and the shape-shifting occupant of an alien spacecraft set free after being frozen for centuries in ice.

Of the three film adaptations, it's Carpenter's The Thing, written by Bill Lancaster, that most resembles the plot of Campbell's novella, from which it borrows character names, the blood test sequence, and the alien's transformative abilities, though the novella and Carpenter's films end on very different notes. Long available in either 12- or 14-chapter formats, Who Goes There was revealed in 2018 to be Campbell's shortened version of a longer novel, titled Frozen Hell, which was published that same year. Blumhouse Productions subsequently announced a film version of the expanded story in 2020.

If you thought Re-animator was gory, read the Lovecraft story

Stuart Gordon's Re-Animator features some of the most outrageously gruesome moments in any horror film of the 1980s, from frenzied, disemboweled zombies to a living (and lascivious) decapitated head. One might think that the torrent of splatter was generated by Gordon, but actually, the source material — "Herbert West – Reanimator," a serialized short story published by H.P. Lovecraft in 1922 — already had enough bloodshed.

Gordon's script streamlined Lovecraft's story, which takes place over the course of several years and even takes its anti-heroes — the arrogant Herbert West and an unnamed narrator — to the battlefields of World War I in search of bodies to re-animate. But the nastiness in "Herbert West" more than equals Gordon's supercharged on-screen gore: West's re-animated subjects carry out multiple murder sprees and, at one point, turn cannibal. Lovecraft also has an animated body without a head (the unlucky soul is a heroic medic whom West revives after a plane crash) which leads a zombie army against West in the blood-soaked, entrails-filled final chapter.

As gory as Gordon's movie is, it's crazy to think that he actually had to reel in the violence for the film version.

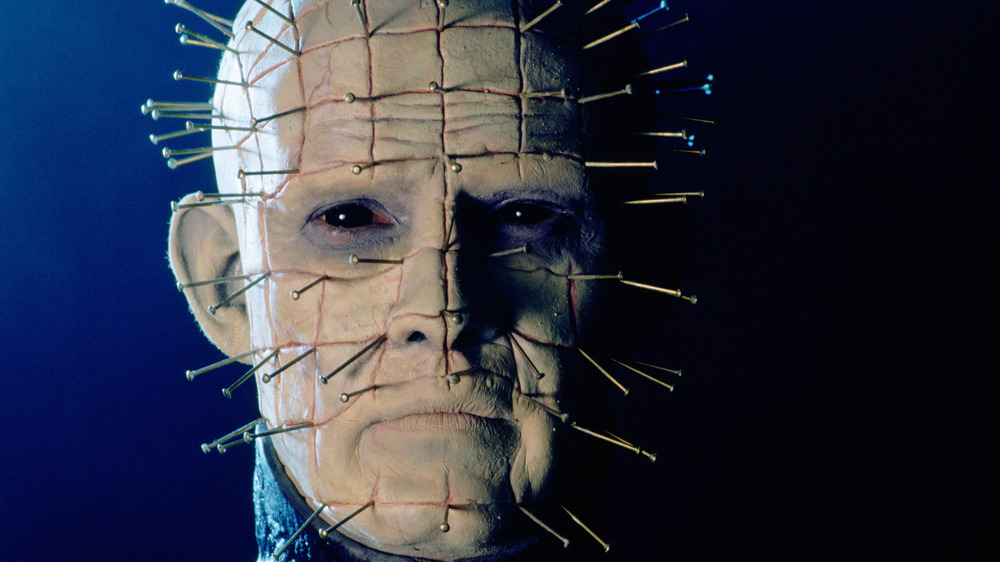

From Hellbound to Hellraiser

One of the most ferociously original horror films of the 1980s, Hellraiser was adapted by author-turned-director Clive Barker from his own 1986 novella The Hellbound Heart. Barker has said in interviews that the reason he wrote and directed Hellraiser was to exert some control over adaptations of his work, having been displeased with feature film versions of Rawhead Rex and what became of his own script for Underworld.

As a result, Hellraiser closely follows the plotline of Hellbound Heart, with only a handful of changes: In the novella, Kirsty is a friend of the ill-fated Rory, whose brother Frank accidentally summons the Cenobites, while in the film, Kirsty (played by Ashley Laurence) is the daughter of Rory, who's renamed Larry and played by Andrew Robinson. The name of the diabolical puzzle box that conjures up the Cenobites is also slightly different: In the novella, it's the Lemarchand Configuration, which Barker dubs the Lament Configuration — a much smaller mouthful — in his script. And speaking of the Cenobites, their S&M-inspired body modifications are, for the most part, almost identical to their description in Barker's story, right down to the mass of pins in the skull of one creature which, while nameless in the book and film, would eventually be known in sequels as Pinhead.

Color Out of Space gets Lovecraft right

"The Colour Out of Space," H.P. Lovecraft's 1927 short story and one of his most popular examples of creeping cosmic horror, has been adapted to film several times, most notably Die, Monster, Die! with Boris Karloff and 1987's The Curse. The most recent and, by many accounts, best screen translation is 2020's Color Out of Space, directed by South African filmmaker Richard Stanley of The Island of Dr. Moreau infamy.

Stanley's version sticks closely to Lovecraft's story about a meteorite that crashes on a New England farm and unleashes bursts of unearthly color that cause horrific mutations to the farm's flora, fauna, and family, which, in the film, is led by a (slightly) restrained Nicolas Cage. Stanley's script adds some dark humor (Tommy Chong plays a local hippie who knows too much) and dashes of modern angst about climate, but for the most part, Color nails one of Lovecraft's core concepts: that entities with powers that defy our imagination exist just outside of our realm of understanding, waiting for the right opportunity to unleash world-wrecking horror.