Dumb Things In Ghostbusters Everyone Ignored

Ghostbusters has a well-earned reputation as one of the greatest comedies of the '80s, and arguably of all time. It has everything you could want, from clever dialogue and engaging characters to spooky slapstick action and sweeping set pieces. It even has a scene where a cellist for the New York Philharmonic mystically animorphs into a demonic dog, which is something that no other movie can claim.

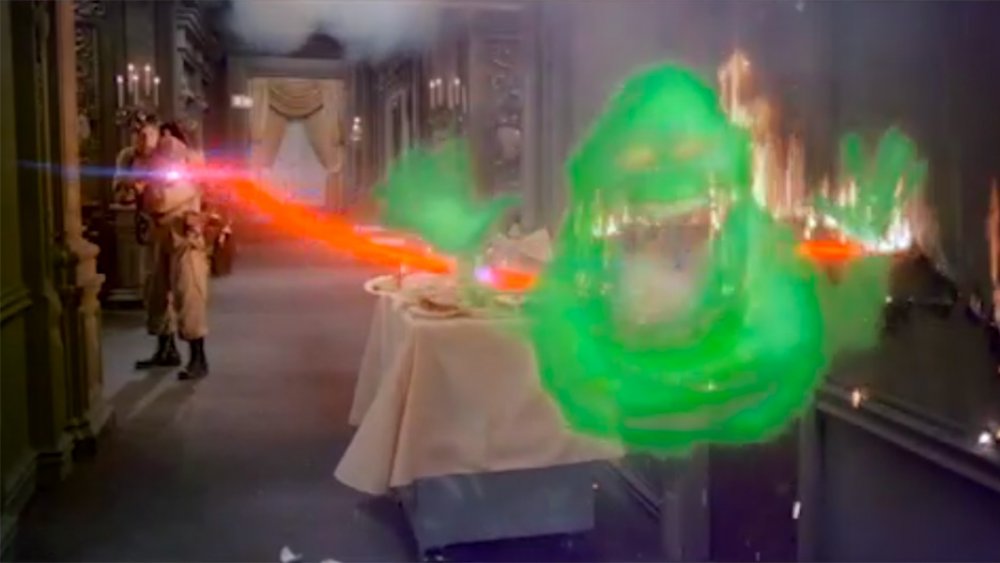

The movie is so beloved, in fact, that it's easy to forgive, or even simply overlook, the fact that there are some things that just don't line up here. Between the coincidental plot contrivances that are even harder to believe than a floating green blob shoving hot dogs in its mouth and holes in the logic that are big enough for the Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man to walk through, there are plenty of dumb things in the 1984's classic Ghostbusters that everyone just ignored.

Walter was right

By and large, Ghostbusters holds up pretty well for a movie that's rapidly approaching its 40th birthday, but there's one aspect of the film that definitely marks it as a product of Reagan's '80s. The ultimate villain of the story might be Gozer the Gozerian, but the real bad guy who gets everything started is Walter Peck, the guy who shows up from the EPA and tries to shackle the Ghostbusters with all those pesky government regulations.

Here's the thing, though: Peck is roughly one million percent correct in virtually everything he does in the film. Just think about it for a second: if you heard that three discredited college professors were running around New York City with what they referred to as "unlicensed nuclear accelerators," and that they were keeping whatever extremely toxic byproducts that resulted in a homemade containment unit that they slapped together out of chicken wire, duct tape, and good vibes, you would probably want someone to look into that. If you found out that they were doing all of this because they wanted to turn a profit by atom-splitting nuclear laser beams at ghosts, you would definitely want someone — preferably several someones, preferably heavily armed — looking into that. Even the most libertarian view of regulatory agencies tends to make allowances for situations that include the words "homemade," "nuclear," and "Manhattan."

For all his brusqueness, Walter Peck is completely justified in checking things out. The only reason he gets hostile to the Ghostbusters is that Venkman, the least qualified member of the team when it comes to explaining how anything works, responds to his incredibly reasonable questions with open hostility. The fact that Peck comes back with only a single cop and a ConEd technician rather than, say, Seal Team Six, is a testament to just how evenhanded he's being.

Artificial Hell

Let's assume, for the moment, that despite all appearances to the contrary, Ray and Egon knew exactly what they were doing when they built their equipment, and that they've managed to build nuclear-powered backpack lasers that are perfectly safe for civilian operation. That's more or less how it works in the movie, after all, and everything seems to work exactly as it's intended — not just the proton packs, but the containment grid that they're keeping in the firehouse. You know, the machine they've built to indefinitely contain the ghosts of people who were so tortured in life that they remained on Earth instead of moving on to the afterlife, which definitely exists? If that's the case, it's a pretty incredible accomplishment!

Congratulations, Egon: you have just created Hell. Or, at the very least, an artificial Purgatory from which there is no escape.

Even if everything's working exactly as intended, the containment grid that the Ghostbusters are using for all of their "vapors, entities, and slimers" is literally just a repository for literal human souls, with no intention of ever letting them go — and in fact, doing so would be absolutely disastrous. The morality and metaphysical implications at play here are both staggering and also never brought up within the film, but one thing is clear: to paraphrase William Shakespeare, Hell is empty and the devils are in a firehouse in Tribeca talking about Twinkies.

Peter Venkman: uniquely unqualified, profoundly creepy

While the whole cast of Ghostbusters is full of fantastic performances, Peter Venkman, played by the inimitable Bill Murray, is definitely the breakout fan-favorite star. It makes sense that he would be, too. Egon gets the deadpan straight lines, Ray is the hapless dork, and Winston sadly doesn't join the cast until 45 minutes into the film (much to the consternation of actor Ernie Hudson, who signed on when the character had a much bigger part). Peter, however, has all the sarcastic, smarmy charisma that would define Murray's career throughout the '80s. In fact, he's so appealing in the part that it's easy to ignore that Venkman is a) little bit dim compared to the other members of the team, and b) kind of a total scumbag.

Let's start with the academic credentials. In his conversation with Walter Peck, Venkman claims to hold two PhDs: one in psychology, and one in parapsychology — which, in one of the movie's most underrated gags, leads to Peck consistently calling a guy who should be a doctor twice over "Mister Venkman" for the entire scene. The first one would explain how he got his teaching position at Columbia, but the second is dubious at best. Parapsychology is usually considered a pseudoscience, and there are virtually no universities that will award a doctorate in the subject. In fact, the only person to ever get a PhD in parapsychology from a major university is Jeffrey Mishlove, who got it from the University of California at Berkley before going on to host a PBS show about alternative views of psychic phenomena, much like we see Venkman doing in Ghostbusters II.

As for the evidence for Peter Venkman: Total Scumbag, well, it's nowhere near as subtextual as the academic stuff, and makes up most of the film. We are, after all, introduced to him in a scene where he's using an experiment in precognition in order to hit on a student. The most damning piece of evidence, though, is one you might've missed. After he shows up at Dana's apartment for their date and finds her to be possessed by Zuul, Venkman calls up to let Egon know that he sedated her with 300 milligrams of Thorazine, an antipsychotic medication with sedative side effects. Which, apparently, he brought with him on a date. In a quantity ten times the usual daily dosage. You know, for completely normal reasons. Maybe this is one that's good to ignore.

Spectrophilia

While he's the most obvious creep in the cast, Peter Venkman isn't the character being featured in the movie's most famously, bizarrely sexual scene. That honor goes to Ray Stanz and the truly inexplicable sequence where he engages in... how can we put this... some intangible mouth fun with a lady ghost.

It's a weird scene for a lot of reasons, the most obvious being that, well, he's giving a whole new meaning to the term "ghost adventure." Aside from that (and the idea that several people thought this would be a perfectly fine thing to toss into a movie that they'd later adapt into a cartoon for babies), one of the strangest things about the scene is the way that it's shot and presented to the audience. The whole thing takes place while Ray is asleep, exhausted during that first busy boom of the ghostbusting business that comes after they clear out the Sedgewick Hotel, and it's not really clear if we're seeing a memory, a dream, or an actual event happening as we watch it (it's awkwardly shoehorned into a montage, having originally been part of a lengthier deleted scene). What is clear is that judging by his anime-style O-face, Ray is having a very good time engaging in some intense spectrophilia.

And that raises the question: we know that Ray is interested in ghosts, but is he, you know, interested in ghosts? Is this why he's so knowledgeable about spirits and the buildings they inhabit? Has he based his entire scientific career on a fetish? Is he just super horny for ghosts, and if so, is it just the ones that are human shaped? Is that why he's so excited to see Venkman get slimed? Is the containment grid just a high-tech metaphysical BDSM dungeon? These are the questions that the movie is forcing us to ask, and it's hard to believe that anyone outside of Ivan Reitman and Dan Aykroyd wanted the answers. We know that bustin' makes Ray feel good, but we're not sure we want to know how good.

No one should be surprised to see a ghost

Here's something that's going to seem painfully obvious: in the world of Ghostbusters, the existence of spirits and haints is a scientific fact. It's sort of the premise of the entire movie, largely because watching people wander around in the dark failing to find ghosts with night vision cameras and radio static wouldn't become a viable form of entertainment for another 20 years or so.

The thing is, the characters within the movie often treat ghosts with the same skepticism as people in the real world, where ghosts are more of a matter of belief. Peck even goes as far as referring to the Ghostbusters as charlatans who are scamming people out of money, which — while a pretty fair assessment of Peter Venkman as a character — is operating from the default position of ghosts being, at best, debatable. And this is despite the fact that ghosts in the world of the film are full-on ghosts with visible translucent bodies, poltergeisting around and causing so much trouble that haunted hotel employees need to be warned about them in advance, as opposed to being, you know, cold spots and creaky floors.

On the one hand, we know that before the sudden upswing in New York's paranormal activity, ghosts are relatively rare. The Ghostbusters mention on their very first call that they haven't had a chance to properly test their equipment, which implies that they just didn't have access to enough ghosts. At the same time, there's enough scholarly research on ghosts that they've been cataloged with various classifications — i.e., "class 5 full-roaming vapor" — and that a couple of brilliant weirdos have made functional and effective equipment for corralling them. It gets even weirder in the sequel where the potential apocalypse that's averted at the end of Ghostbusters is chalked up to mass hysteria, despite the fact that there would absolutely be news footage of a ten-story marshmallow man and the Holy Trinity Lutheran Church didn't stomp itself.

Follow the money?

Ghostbusters understandably keeps the specifics of our heroes' methods pretty vague, but it stands to reason that proton packs and containment units don't come cheap. Even before you get to the part where they've been modified with experimental equipment that couldn't possibly be cheaply mass-produced, we're talking about a starting investment of three electrostatic particle accelerators that are small enough to be worn on a person's back. That's a pretty expensive place to start. So where the hell did the Ghostbusters get the money for all this?

As silly as it seems to apply practical, real-world concerns like startup capital to a movie about fighting a giant ghost marshmallow, the team's financial difficulties are the focus of a pretty big chunk of the first half of the movie, which invites curiosity. We're talking about a price tag that's in the millions are the very least. Professors at Columbia — even the non-tenured kind that get summarily fired for their dubious theories and worse ethics — aren't exactly scraping by in terms of salary, but they're definitely not pulling down the nine figures that they'd need to get started on a career in Ghostbusting. They even ask the question themselves in the film. "This Ecto-Containment system that Spengler and I have in mind is going to require a load of bread to capitalize," Ray points out. "Where are we going to get the money?" Venkman's response: "I don't know." Same here, buddy.

The only real answer here, and the one that the movie seems to suggest, is that the initial round of equipment was funded by Columbia University, while the rest of the money for the business and its paraphernalia came from Ray mortgaging his house three times. Folks, that must be one hell of a house.

The Real (Estate) Ghostbusters

Maybe particle accelerators are cheaper than we think. Maybe they're actually pretty affordable, or at least affordable enough that you could cover the cost of three of them by getting a triple mortgage on a house in Morrisville, NY (that's where Ray grew up, according to the cartoon), all while the country was recovering from a deep recession. That seems unlikely, but it's an easy enough set of events for which to suspend your disbelief.

You could even stretch it and say that said triple mortgage resulted in enough money to get the proton packs, the traps, the containment grid, a set of matching uniforms with custom logos, a vintage 1959 combination ambulance/hearse that was completely customized and repaired, television airtime and a production crew for advertising, and one (1) large dinner of Chinese food. If we're willing to accept everything else that happens in this movie, like demonic architecture, that all seems possible.

Here's what's absolutely impossible to believe: that you could get all of that and have enough money to purchase a corner property in lower Manhattan, let alone a historic building that dates back to 1903, no matter how much of a fixer-upper it might've been. Seriously, despite Egon's grumpy claims about the firehouse's location, Tribeca wasn't exactly a "demilitarized zone," even in 1984. Even without the considerable remodeling — like, you know, new lockers, a fresh coat of paint, putting in a synthetic hell to contain the souls of the five boroughs that have been denied even the peace of the grave — that is downright preposterous.

They lied to us through song!

Ghostbusters is more than a famous film. It's a genuine pop culture phenomenon that's maintained its appeal for decades, spawning a theatrical sequel, a movie reboot, a handful of cartoons of various quality, multiple comic books, and a roleplaying game that does a surprising amount of world-building. Even with all that, though, the single most well-known piece of the entire franchise might just be the theme song. It was a hit single that spent three weeks at the top of the charts, and installed "who ya gonna call?" into the pop culture lexicon with an unshakeable permanence.

And it's also a pack of damn lies.

No, not the part where Ray Parker Jr. allegedly ripped off the frankly inferior "I Want a New Drug" by Huey Lewis and the News, although that did result in a lawsuit and a settlement. We're talking about the content of the song. Along with "who ya gonna call" and the increasingly disturbing "bustin' makes me feel good," the most oft-quoted line in the song is "I ain't afraid of no ghost." Take a look at the movie, though, friends. When they see a ghost, those dudes are terrified! Well, except Ray, but as we've seen, his reaction is a completely different problem to deal with. Still, plot holes and inconsistencies are one thing, but lying through a catchy theme song? Unforgivable!