Moviemakers Who Refuse To Use CGI In Their Films

In the early 1990s, CGI — computer-generated imagery — was pioneered by films such as "Terminator 2: Judgment Day" and "Jurassic Park." A story from the latter film's production was rather telling: As stop-motion animation specialist Phil Tippett viewed the dinosaurs brought to life by Industrial Light and Magic via CGI, he quipped (via Den of Geek), "I think I'm extinct."

Since then, for better or worse, CGI has become a dominant force in mainstream cinema. Oscar-nominated CGI specialist Andrew Whitehurst commented in a column for The Guardian that CGI can be a powerful creative tool for both big and lower-budget films, provided that it is used innovatively. However, another Guardian writer expanded on this point of "innovation," or lack thereof, criticizing the "laziness" of modern CGI and how it serves the "palatable routine" of big budget mainstream cinema.

While very few directors actively reject CGI, there is still a growing number of filmmakers who think it should be used with caution. Typically, these directors view the technology as an accessory rather than a raison d'être; a tool that is complimentary rather than absolute. Here are the moviemakers who refuse to use CGI in their films.

Kathryn Bigelow

Kathryn Bigelow has a long record of using impressive practical effects. "The Hurt Locker," arguably her most famous film, was praised for its documentary-style authenticity, especially the nerve-wracking opening sequence. In an interview with First Showing, Bigelow was asked if CGI was used, "None to speak of," she replied. "It was all in-camera, and I had a phenomenal camera crew ... we came back with a lot of footage."

Some 20 years prior, in 1987, Bigelow worked on "Near Dark," a vampire film starring Bill Paxton and Lance Henriksen. Describing it as "one of the best vampire movies ever made," Alan Jones of the Radio Times praised the film as a "visually stunning package." Film critic Peter Travers was also impressed by its visual style, describing it as "gorgeous and gory" while complimenting Bigelow's "artful handling of the magic and menace of the night."

Another triumph of the practical was "Point Break," which opened on July 12, 1991. With its practical surf scenes and skydiving sequences, the electric energy of that film would make a sharp contrast with a remake in 2015, which Peter Bradshaw called out in particular in his one-star review for its "bad CGI."

Christopher Nolan

Anyone who has seen at least "Interstellar" will realize that Christopher Nolan does not refuse to use CGI. However, when he does use it, the five-time Oscar nominee is very selective. Take the hallway sequence in "Inception," for example. You'd think that somewhere, somehow, there was at least a sliver of CGI. But no, Nolan used neither green screens nor CGI but an actual tumbling hallway.

On the subject of CGI, the director told DGA, "Computer-generated imagery is an incredibly powerful tool ... [But] if it's been created from no physical elements and you haven't shot anything, it's going to feel like animation ... I prefer films that feel more like real life, so any CGI has to be very carefully handled to fit into that."

This attitude is seen throughout his filmography. In capturing everything from the frozen planet scenes in "Interstellar" to the freight train sequence in "Inception," Nolan has found a practical solution for the impressive scale of his set pieces. The "Inception" freight train, for example, which careens through the streets of Los Angeles, was in fact a truck dressed up as a locomotive. The vast cornfields in "Interstellar" weren't CGI but a real batch grown by the production team. Once filming had wrapped, the corn was reportedly sold. Another notable moment is the truck flip in "The Dark Knight." The sequence was achieved through practical direction and in-camera effects.

Brandon Cronenberg

David Cronenberg, the director known around the world for his macabre "body horror" films, famously pushed the envelope of horrific practical effects. After the exploding heads of "Scanners" and the cancer gun in "Videodrome," Cronenberg entered mainstream filmmaking with "The Fly," which featured some horrifyingly grotesque effects that won the Academy Award for Best Makeup in 1987.

Filmmaker Brandon Cronenberg is not only the son of David Cronenberg but also the director of "Possessor," an intense sci-fi horror film that follows in the tradition of much of the violent imagery that his father presented to the world. The younger Cronenberg told the Guardian that "CGI violence feels a little floaty and unreal."

For example, there is a moment in "Possessor" in which a fire poker is put to monstrous use. Describing it as the "eyeball moment," Cronenberg told the Guardian, "People have been shocked [by it], but there's an incredibly graphic knife to the eye in 'John Wick 3.' It's just that the reaction is less strong there because it's digital. There's a tactility that's lost when you abandon practical effects."

Patty Jenkins

According to Den of Geek, "Wonder Woman" director Patty Jenkins has brought a "real people doing the real thing" philosophy to action filmmaking. Despite this intention, however, the first "Wonder Woman" film climaxed with what actor Chris Pine described as "cataclysmic computer graphics explosion nonsense."

This may have inspired Jenkins to double down on her commitment to practical effects in "WW84," the second film in her "Wonder Woman" series. "Patty really made a point about wanting to have a minimum amount of CGI in our movies," lead actress Gal Gadot explained, "When you see it in the movie ... you can just tell that it's the real deal."

Jenkins' practical sensibility made the shoot the hardest of her career but also one of the most fulfilling. "It took longer to shoot and it's very tiring on your body," she admitted. "But then you see the result and I was so satisfied ... You can tell the difference between real action to CGI action."

Quentin Tarantino

Quentin Tarantino is a famous proponent of practical effects, displaying his bloody relish for them in films such as "Reservoir Dogs" and the "Kill Bill" series. According to the Guardian, Tarantino once described CGI as "computer game bulls***." Declaring himself as "old school," the director added, with much profanity, that "my guys are all real ... there's no [CGI]. I'm sick to death of all that s***."

A famous student of cinema, Tarantino's appreciation for practical effects was influenced by horror films of the 1970s and '80s. "I love John Carpenter's 'The Thing,'" Tarantino said on the "Late Show with Stephen Colbert," adding, "Rob Bottin's effects in the movie are some of the greatest practical special effects ever put on a movie theater screen." For his debut feature, "Reservoir Dogs," Tarantino took the premise of Carpenter's film — a isolated group of men wracked by violent paranoia — and spun it into a noirish crime film. Another nod to "The Thing" was in "The Hateful Eight," another male-driven film set in tense isolation.

George Miller

In the last 20 years, few films have emphasized practical effects more than "Mad Max: Fury Road." BBC critic Nicholas Barber wrote that "Fury Road" was a "defiantly individual riposte to those committee-led blockbusters which are built on CGI and designed to sell toys."

Director George Miller may not have intended for "Fury Road" to be a "riposte," but the Australian filmmaker told Entertainment Weekly that CGI "sort of takes me out of the experience," adding that he was cautious about using too much of it in his movie. He also said that watching a film should be a completely immersive experience that feels as real as possible. It seems that this was a guiding principle of the film, with Miller committing himself to using real cars, real people and real stunts: "We decided to literally do every car that's smashed is smashed, every stunt is a real human being, even the actors do a lot of their own stunts, and so on."

However, even with this flair for the practical, Miller noted that about 10% of the effects were digital (via Business Insider). Andrew Jackson, the film's visual effects specialist, was more precise, telling FX Guide, "The reality is that there's 2000 VFX shots in the film. A very large number of those shots are very simple clean-ups and fixes and wire removals and painting out tire tracks from previous shots, but there are a big number of big VFX shots as well."

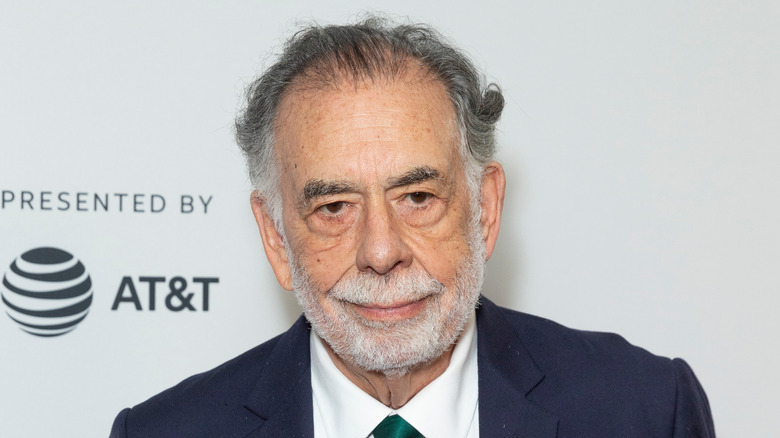

Francis Ford Coppola

Francis Ford Coppola has directed some of the most enduring classics of American cinema, namely "Apocalypse Now," and the first two "Godfather" films. Of course, those films were released in the 1970s, long before CGI was an option for filmmakers. However, this was not true of "Bram Stoker's Dracula," which was released in November 1992, more than a year after the CGI triumph of "Terminator 2."

During principal photography of "Dracula," Coppola fired his visual effects team because they insisted on using CGI. Instead, Coppola worked with his son Roman, creating numerous in-camera and practical effects (via Vashi Visuals). The effort was a great success. Many critics noted the film's "luscious" aesthetic, including Variety's Todd McCarthy, who described "Dracula" as a "sumptuous engorgement of the senses" (via Rotten Tomatoes). In fact, for some viewers, like the Chicago Reader's Jonathan Rosenbaum, Coppola's energetic visual style and overall conceptual imagery compensated for the film's narrative issues and what he described as a cluttered screenplay.

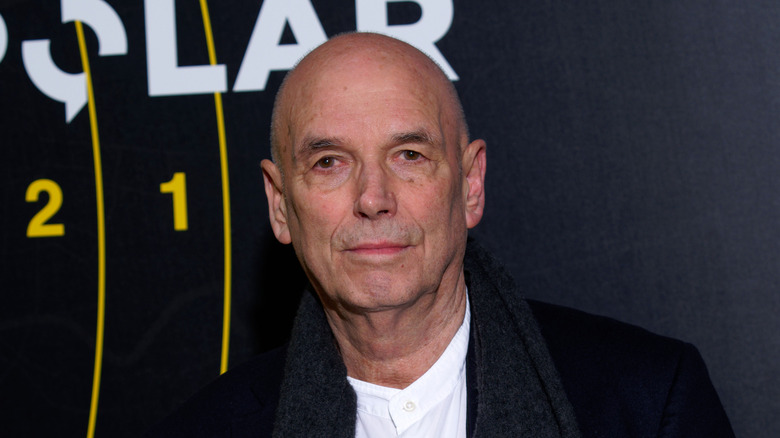

William Friedkin

Responsible for New Hollywood classics such as "The French Connection" and "The Exorcist," the amusingly frank director William Friedkin has reservations about CGI. Speaking in Lucca in 2016, Friedkin explained that a newspaper reported Friedkin as believing "the devil was in technology." Friedkin corrected the report, noting that he had used small amounts of CGI in his recent projects but felt that in the wider industry, technology was replacing character and story.

It's no surprise that William Friedkin has reservations about computer generated images; the director created some of the most memorable practical scenes of his generation. "The French Connection" boasts one of the greatest car chases in cinematic history, and it was achieved not with digital trickery but with old-fashioned antagonism. In an interview with the AFI, Friedkin explained how he riled up his stunt driver, Bill Hickman, by mocking his ability to drive.

"Bill, you haven't shown me a damn thing," Friedkin told Hickman, "I heard what a great stunt driver you were and this thing is lame." Insulted by this upstart director who was 14 years his junior, Hickman invited Friedkin for a "ride." With the cameras rolling, Hickman drove at 90mph for 26 blocks through Brooklyn without any permission from local authorities. Friedkin used much of the crazed footage in the chase scene, creating a new cinematic benchmark.

Spike Lee

Spike Lee is ambivalent on the subject of CGI. Acknowledging how the technology has changed the industry, Lee told CNET that "the trick is how do you use these CGI images to tell a story and to make it original." For Lee, the problem is that many CGI-heavy films lack originality: "It's like the same effects house is doing everything," he said. "They all look the same."

The subject of CGI taps into Lee's wider concerns about filmmaking, which he fears is being controlled by technology rather than artists. However, the "Do The Right Thing" director is not a Luddite. He shoots most of his movies digitally instead of using film, and he has secured funding through Kickstarter campaigns too. But Lee is also a student of cinema and, like his fellow cinephiles Quentin Tarantino and Christopher Nolan, still prefers to shoot on film when his budget allows for it.

Martin Campbell

In "Goldeneye" and "Casino Royale," director Martin Campbell showed that you don't need CGI to create spectacular cinema. It's a matter of opinion, of course, but the absurd skyscraper freefall scene in "Hobbs and Shaw" has only a shred of the tangible risk and danger we experience in "GoldenEye" as James Bond, played for the first time by Pierce Brosnan, bungee jumps down an enormous Soviet dam.

A decade later, in "Casino Royale," Campbell directed a practical stunt that set a new world record. According to 007, the Aston Martin DBS car flip, which was achieved using an 18-inch ramp, rolled the car seven times, setting the Guinness World Record for the most barrel rolls by a car. Compare the strength of practical car crashes to the one in 2011's "In Time," which features a thoroughly CGI crash scene involving a Jaguar E-Type and a strip of puncture stripes. Campbell also avoided using CGI in "The Mask of Zorro," explaining (via No Film School), "At the time, CGI was in its infancy and we never even contemplated using it. We used none because we didn't need it."

Ari Aster

Ari Aster is another director who uses CGI only when no practical alternative is feasible, such as the hallucinations in "Midsommar," Aster's second feature film. But Aster challenged his special effects crew with far grislier practical tasks. Vulture examined the bloody precision used in "Midsommar," which features a dozen deaths by way of asphyxiation, burning and, most notably, savage blunt force trauma. Many of these deaths required the creation of full prosthetic bodies, which was the responsibility of veteran make-up designer Iván Pohárnok.

One of Pohárnok's most creative innovations on the set of "Midsommar" was for the shocking head-crushing scene. Ideally, Pohárnok's team would have created the prosthetic head — a six-week undertaking — that would have been crushed in just one take. But scenes are rarely done in one take, so Pohárnok needed to get creative. His solution was to create a prosthetic head containing button-operated pneumatic cylinders that could smash and "unsmash" itself, all the while spraying fake blood everywhere. "It worked beautifully," Pohárnok explained. "We just pressed the button and everything popped back into the original, pristine face."

Ryan Coogler

Ryan Coogler is no stranger to heavy CGI. He directed Marvel Studios' "Black Panther," after all, a film loaded with visuals requiring the use of computer-generated imagery. However, the filmmaker refused to use CGI to recreate Chadwick Boseman's character in the sequel, "Black Panther: Wakanda Forever" (via Syfy). Boseman, who had led the "Black Panther" cast in the role of T'Challa, died of colon cancer on August 28, 2020, and his death hit Coogler very hard.

"I'm incredibly sad to lose him," Coogler told the "Jemele Hill Is Unbothered" podcast. "But I'm also incredibly motivated that I got to spend time with him ... You spend your life hearing about people like him." The plot of the new film and the fate of T'Challa remain a mystery for now, but a CGI likeness of Boseman is not in the cards. Speaking with Argentine newspaper Clarin (via Insider), executive producer Victoria Alonso said, "There's only one Chadwick, and he's not with us."

J.J. Abrams

J.J. Abrams has used plenty of CGI in his television and film productions, yet the director has also made efforts to use practical effects, especially in "Star Wars: The Force Awakens," which was released during what the New Yorker described as "Hollywood's turn against digital effects."

Speaking in a behind-the-scenes documentary, production designer Rick Carter explained, "J.J. is trying to make sure these movies have a physicality to them." To achieve this "old school" approach, Abrams' crew designed real sets, scouted real locations, and used real sunlight.

This wasn't always feasible, especially on a project as large and as complicated as "The Force Awakens," but the team were able to strike a balance between the digital and the practical. Abrams said (via Collider), "I feel like the beauty of this age of filmmaking is that there are more tools at your disposal, but it doesn't mean that any of these new tools are automatically the right tools ... we went very much old school."

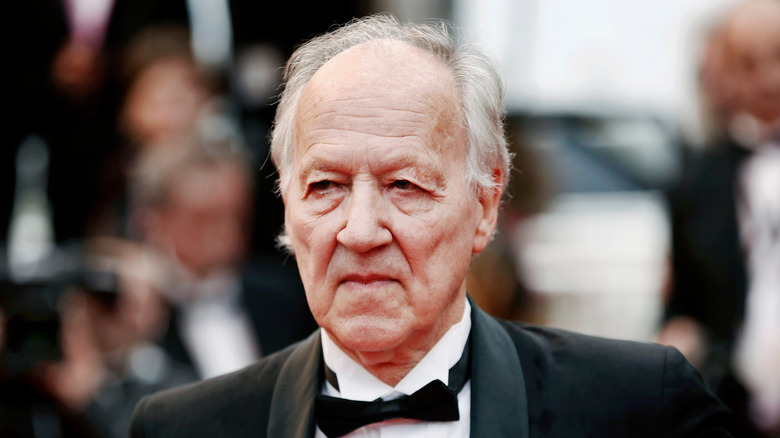

Werner Herzog

Bavarian director, screenwriter, and actor Werner Herzog made an impression on the world stage with films such as "Aguirre, Wrath of God" and "Fitzcarraldo." Released in 1972 and 1982, respectively, both were wild, elemental films, especially "Fitzcarraldo," which featured a scene in which a real 320-ton steamship is pulled up a muddy Peruvian slope (via LWL).

To a new generation of "Star Wars" fans, Herzog may be best known for his performance as The Client in "The Mandalorian." Despite having never seen a "Star Wars" film, Herzog was impressed not just by the TV show's script but also by the Baby Yoda puppet. "I have seen it on the set," Herzog told Variety, "it's heartbreakingly beautiful."

When Herzog discovered that the puppet could possibly be replaced by CGI, the actor branded the crew "cowards" and insisted that they leave it in place instead of removing it to get the backup shot (via Vanity Fair).

Herzog explained his view about CGI on The Portal podcast. Asked if he would use CGI on a project such as "Fitzcarraldo," Herzog answered "no" without hesitation. He added, "I don't think that digital effects will ever create an equal experience [to practical effects]."