The Real Reasons Why Waterworld Bombed At The Box Office

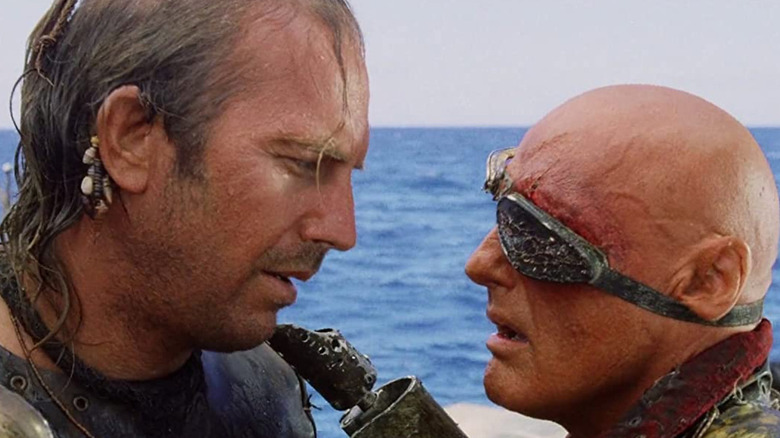

One of the most notorious Hollywood action-adventure films is 1995's "Waterworld," set in a version of Earth that is almost completely submerged into the sea after the polar ice caps melt. Starring Kevin Costner as a stoic wanderer known simply as the Mariner, the movie features seafaring dictators, jet ski chases across the high seas, and floating communities struggling to survive in this post-apocalyptic future.

With Costner's career in full swing (with hits like "Dances with Wolves," "Bull Durham," "Field of Dreams," and "The Bodyguard" under his belt), this ambitious picture could have easily been a big hit. However, the film's production was famously troubled, including creative clashes between Costner — who also produced the film — and director Kevin Reynolds. Worse, "Waterworld" failed to win over critics or the box office upon its theatrical debut.

Here is the story of how one of 1995's biggest action movie spectacles belly-flopped with the public when it premiered, from the production's derailed working conditions to competing views on how exactly the movie would be made.

The movie began as an admitted rip-off of Mad Max

The origins of "Waterworld" can be traced as far back as the Australian post-apocalyptic movie series "Mad Max," directed by George Miller and starring Mel Gibson as the gruff antihero. "Mad Max" spawned a whole line of pastiches and rip-offs, with legendary B-movie producer Roger Corman among those in Hollywood interested in cashing in on the film's gritty and grim aesthetic. So Corman's associate Brad Krevoy met with then-new screenwriter Peter Rader and offered to pay for him to write a similar screenplay, but Krevoy balked at Rader's idea to set the film on water, rather than in a desert wasteland.

Rader still wrote that initial concept into a screenplay in 1986, but the script wasn't actively shopped around Hollywood until 1989. Costner and Reynolds became attached to the project in 1992, with Rader providing six or seven drafts before the two replaced him with their writers. Rader himself observed writing the multiple drafts left him feeling "burnt out" on the project, which proved to be a harbinger for things to come for the production.

The filmmakers ignored Steven Spielberg's advice for the production

Reynolds and Costner were both accomplished filmmakers in their own right by the time active production began on "Waterworld," with Costner winning Academy Awards for directing and producing "Dances with Wolves." However, as the two began working together on "Waterworld," they were approached by veteran filmmaker Steven Spielberg, who had specific advice for the production stemming from his own experience helming "Jaws." Unfortunately for all parties involved, Spielberg's words of wisdom were largely ignored, which foreshadowed the catastrophic conditions ahead.

Rader recalled that Spielberg personally called the production to warn them against filming in open water rather than on a controlled set. Spielberg reportedly had a miserable experience filming "Jaws" years prior in open water conditions and wanted "Waterworld" to avoid the mistakes he endured. Instead, "Waterworld" proceeded to film in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Hawaii and suffered from unpredictable weather conditions for the bulk of its principal photography.

Costner and Reynolds had a severe falling out during post-production

Costner and Reynolds already had a collaborative history before working together on "Waterworld," including working together on the 1991 movie "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves." However, despite the box office success of their last joint venture, the two men had a falling out during that film production, disagreeing on Costner's choice of accent, co-star Alan Rickman's prominence, and the final cut. After the fractious experience, the two decided to work together again on "Waterworld," but past professional tensions between the two would reignite once again.

With Costner going through a public divorce amid "Waterworld" filming, he and Reynolds reconciled, though this collaborative peace would eventually erode as production continued. By the time the movie's post-production phase began, creative clashes flared again, with Rader claiming that Costner went as far as to lock Reynolds out of the editing bay. Reynolds eventually quit the production altogether, and the two were not on speaking terms in the weeks leading up to the movie's release, making for an unusual promotional tour indeed.

Costner and Reynolds brought in competing writers

The early signs of Costner and Reynolds' creative friction began months before the start of principal photography, according to Reynolds. In the years since Rader sold his original script, "Waterworld" saw several rewrites, undergoing seven different drafts by the time Costner and Reynolds became attached. Rader himself was sidelined, with Reynolds deciding further drafts should make the overall tone of the movie more serious than Rader had originally envisioned.

Costner and Reynolds had conflicting visions for what "Waterworld" should be, with Reynolds leaning more into the science-fiction possibilities by giving the Mariner gills, while Costner wanted a more straightforward action hero. With the script still unfinished by the time principal photography began, Costner brought in his own writers, to Reynolds' chagrin. Costner even reportedly went as far as to rewrite his own lines of dialogue in the midst of filming to match his vision for the movie.

Finicky weather and set changes ballooned the production budget

Spielberg's warning to the "Waterworld" production regarding filming locations proved to be prophetic and extremely costly words of caution for the cast and crew. The floating production caused intense bouts of seasickness for the cast and crew while the sets themselves cost more than initially budgeted, including an atoll budgeted for $1.5 million ultimately costing $5 million to construct. The production was regularly plagued by intense winds that prevented filming and an unexpected gale nearly crushing Costner against a ship's mast during one scene.

Throughout principal photography in Hawaii, a passing hurricane sank the atoll, requiring it to be excavated from the ocean floor. With the unpredictable water and wind conditions delaying filming and the region's hurricane season approaching, the production relocated to the California coast in October. These conditions and delays caused the budget to swell up to $175 million, with conflicting reports placing the original budget at $65 million while some had it just below $100 million.

Joss Whedon's rewrite suggestions were largely dismissed

In addition to all of the competing screenwriters and numerous new drafts since Rader's initial "Waterworld" screenplay, Joss Whedon was also brought in during filming to help rewrite the movie's closing act. Whedon had previously performed uncredited rewrites on several major Hollywood movies, including 1994's "Speed" and 1995's "The Quick and the Dead," earning him a reputation in the movie industry as a solid script doctor. However, Whedon's experience joining the "Waterworld" production to similarly provide his expertise proved to be a much more thankless task for the screenwriter.

According to Whedon, the final act of "Waterworld" had "no water" in the shooting script and his time with the production was spent taking notes from Costner. Whedon claimed that Costner's ideas and contributions to the story were considered sacrosanct by the rest of the crew and his seven weeks with the production "accomplished nothing." Whedon noted that he added some puns and scenes to the "Waterworld" script but couldn't watch the movie in its entirety because it "came out so bad."

The movie's crew saw several major departures during production

Between all the behind-the-scenes contentious behavior, exorbitant budget, and highly uncooperative weather, the troubled production saw several major crew members leave in the midst of filming. The "Waterworld" crew totaled over 500 members in all to bring the ambitious movie to life but the poor working conditions and prolonged production schedule resulted in a number of unplanned departures. Crew members were reportedly exhausted from the extended production period, with injuries running high due to the safety protocols and procedures being underfunded compared to the rest of the budget.

Production designer Peter Chesney and effects liaison Kate Steinberg were both reportedly forced off the set during August 1994, with first assistant director Alan Curtiss leaving the production soon thereafter. Prior to his departure, Curtiss argued with the studio for more time scheduled for principal photography, which ultimately ran longer than anticipated. And with "Waterworld" floundering, the filming schedule lasted longer than even Curtiss originally predicted.

The movie's filming schedule took significantly longer than expected

Under its original production budget, "Waterworld" was originally given 96 days by the studio to complete its principal photography though this schedule would quickly be increased. Shortly after filming began in June 1994, the principal photography schedule was increased to 120 days once the scope and difficulties of the production became clear. However, even this extension proved to be woefully inadequate for the creative team to finish the movie as planned, with over a month of filming added to the schedule.

The "Waterworld" filming schedule was eventually extended to 166 days, including the production relocating to California to improve its working conditions. Given his responsibilities as both the star and producer of the movie, Costner was on set 157 days during filming, working six-day weeks to oversee the project. This extended filming period led to a rush post-production phase as the studio scrambled to get its costly movie ready in time.

The post-production phase was a rushed work in progress

With such a prolonged principal photography phase, the studio initially set a five-week period to allow the filmmakers to edit "Waterworld" in order to meet its July 1995 release date. While Costner argued with the studio to allow Reynolds more time for post-production to polish the final cut, Reynolds agreed to the five-week period he was given. However, creative clashes between Costner, Reynolds, and the studio over the movie's runtime resulted in Reynolds quitting the production altogether and leaving post-production in limbo.

With Reynolds' unfinished "Waterworld" cut reportedly set at 160 minutes, the studio was concerned with releasing a summer blockbuster nearly running for three hours. Based on test screening responses, Costner took control of post-production and whittled down the runtime to a more manageable 135 minutes. While "Waterworld" was indeed released in July 1995, the movie was still filming establishing shots of the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California as late as June 1995.

The movie endured harsh press before it was even released

With its swelling production budget, troubled accounts from behind-the-scenes, and behind schedule principal photography period, "Waterworld" gained a notorious reputation months before its release. News outlets unfavorably compared "Waterworld" to the previous films "Ishtar" and "Heaven's Gate," both of which similarly endured costly productions with low box office earnings and critical scorn. This widespread negative word of mouth would help sour the general public on "Waterworld" weeks before the movie was even released, undoubtedly impacting its domestic theatrical run.

"Waterworld" opened domestically to over $21 million and went on to earn over $88 million at the American box office, but this was below the studio's expectations for the expensive blockbuster. Even after factoring in the movie's international box office earnings, "Waterworld" still fell short of its costs, after taking into account the price of marketing and distribution. In the years since its original theatrical run, "Waterworld" has managed to move into a level of profitability, factoring in revenue from home video and licensing; however, its notorious reputation remains afloat.