The Best Moments In West Side Story

Steven Spielberg's long-awaited remake of "West Side Story" is finally here, and it's being hailed as one of the year's best films. Originally developed as a Broadway musical in 1957, and then a Hollywood film in 1961, "West Side Story" tells the tale of gang violence in Manhattan's Upper East Side. On one side, the Jets are made up of white juvenile delinquents, second or third generation Americans of Irish, Italian, and Polish descent. On the other side, the Sharks are comprised of Puerto Ricans, new arrivals looking to build a better life in Manhattan. The racial tensions quickly lead to violence and gang warfare. In the midst of the hatred between these two groups, the former leader of the Jets, Tony, falls in love with Maria, the sister of the boss Shark, Bernardo.

Based on Shakespeare's classic play, "Romeo & Juliet," the past 60 years have seen "West Side Story" become just as iconic as its source material; the music by Leonard Bernstein and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim are as catchy today as they were when they were first written. Spielberg's new take on "West Side Story" retains their timeless tunes while updating the production values and adding new wrinkles to the story of star-crossed lovers in the slums of Lincoln Square.

From the outstanding production design to beautiful showcases of ballet captured on camera by Spielberg in full-on auteur mode, here are our favorite moments in the new "West Side Story."

New York is changing

The eponymous Upper West Side of Manhattan was in a state of flux back in the late 50s and early 60s thanks to the so-called "urban renewal" programs initiated by Robert Moses, who sought to beautify New York City, no matter how many poor communities he had to displace along the way. The slums of the Upper West Side were high in crime and a haven for youth gangs, hence why it was chosen as the setting for "West Side Story" in the first place. Today, after decades of gentrification and the building of Lincoln Center, the Upper West Side is a neighborhood for New York's more wealthy denizens, while its former residents and their descendants found themselves driven north to Harlem, Washington Heights, the Bronx, and parts of Westchester.

In the new "West Side Story," this looming gentrification hangs over the neighborhood like a Sword of Damocles, adding an extra layer of tragedy to the story; since the gangs are fighting over turf, but that turf is about to be demolished by the government, then they fight only for the sake of their own hate. The very first scene features a sign advertising the construction of Lincoln Center, and numerous other scenes allude to the urban renewal that will change the neighborhood forever.

Fun Fact: In real life, some of the tenements of the Upper West Side had their scheduled demolition postponed so the 1961 "West Side Story" could incorporate the location into the production.

Actual Latinos!

While the 1961 film is still a beloved classic, it nevertheless has some elements that don't quite hold up in 2021. Most notably, the Puerto Rican characters are played almost exclusively by white actors in dark makeup. The sole Puerto Rican in the cast, Rita Moreno, had to wear "brownface" makeup to match her darkened co-stars. Still, she won an Oscar for her performance, as did George Chakiris, who played Bernardo.

For the remake, the production enlisted the help of actual Latinos to play the Puerto Rican roles. Maria is played by Rachel Zegler, who is half-Columbian, while Bernardo's actor, David Alvarez, is Cuban-Canadian, and Ariana DeBose, who plays Anita, is Afro-Puerto Rican. There will inevitably be detractors who declare the film offensive for not hiring exclusively Puerto Rican actors, but it's undoubtedly a huge improvement from the original. Also noteworthy is the amount of un-subtitled Spanish dialogue in the film, the meaning of which can be gleaned through context. This reinforces the notion that "West Side Story" is a Latino American story as much as it is a story of white Americans.

Anybodys

The Jets are a gang comprised of white boys from the street, which includes Anybodys. Their characterization varies depending on the production and is thus open to interpretation, but most versions are easy to interpret as trans, especially the two cinematic incarnations. In the 1961 film, Anybodys (played by Susan Oakes) is constantly dismissed by Riff and the Jets for being a girl, but they persist and is eventually accepted by Ice, the de facto leader of the Jets, who says, "Ya done good, buddy boy."

In the new film, Anybodys (played by Iris Menas) initially appears as something of a tagalong character who follows the Jets more than they actually interact with them. Eventually, Anybodys gets locked up along with the other Jets, and is placed in the women's side of the holding room, with the more overtly male Jets on their own bench. When the Jets hassle Anybodys over their gender, calling them a girl, Anybodys shouts, "I ain't no girl!" and pounces on the other gang members, throwing punches that catch everyone off guard, even the cops.

Overall, Anybodys has always been a revolutionary character for trans theater enthusiasts, and this new iteration reinforces that notion without derailing the film into a gender identity polemic. Anybodys is who they are, and that's that; if you've got a problem with that, be ready for a fight.

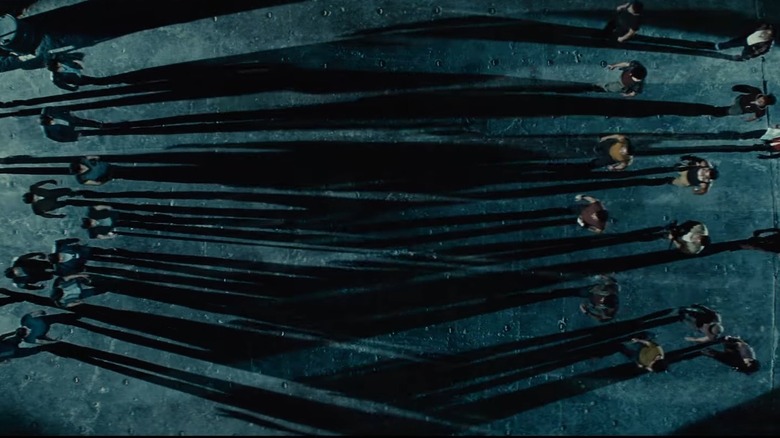

The dance

Tony and Maria first meet at a dance attended by both gangs. Initially, the dance is willfully segregated, with each gang dancing with their dates on their respective side of the gymnasium. Even when the emcee tries to get the dancers to intermingle, it doesn't take, and the dance nearly breaks down into a brawl.

The song, "Dance at the Gym," is played with a near-manic energy beyond that of the original movie, and the new dancing has extra energy to match. The dance is where Spielberg's direction, and the cinematography from Janusz Kamiński, really takes hold. The limited confines of the gymnasium and the lack of vocals in "Dance at the Gym" force the focus squarely on the dancing. Spielberg treats the dancers with the same respect and dedication as the stuntmen in any "Indiana Jones" movie, drawing attention to their incredible talent with long takes and sharp camera movements that heighten the dancing just like the best of his action/adventure movies.

When Maria and Tony notice each other and make an instant love connection, racial tensions be damned, the production design kicks into overdrive, with the lighting changing to reflect how the world simply looks different when you're in love. This sense of romantic whimsy underscores most of Tony and Maria's scenes and elevates "West Side Story" beyond a mere remake of its source material, but a brand new interpretation of a timeless love story.

Tony and Maria, 'Maria,' 'Tonight'

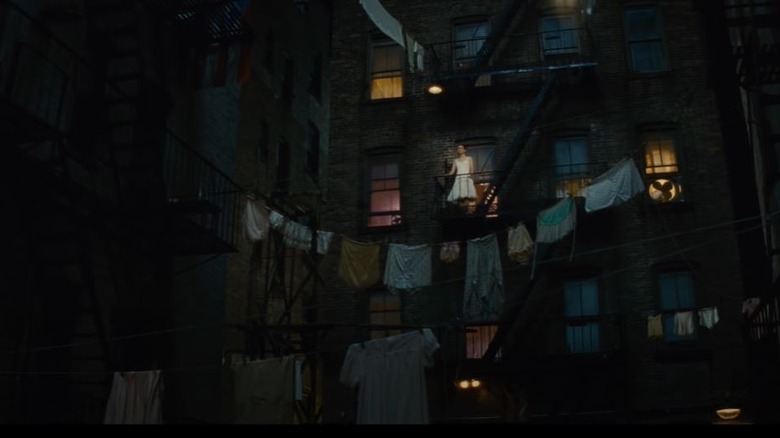

The whirlwind romance between Tony and Maria is cemented by two songs: "Maria," a notoriously difficult solo number for Tony, and "Tonight," a duet between him and Maria, sung in the show's version of the classic "Romeo & Juliet" balcony scene.

For "Maria," Ansel Elgort's serviceable performance is enhanced by Spielberg's stellar direction and creative use of visual effects, which accentuate the beauty that surrounds people in love — even if they're currently in a rundown slum scheduled for demolition. He doesn't throw himself into the dramatic nature of the lyrics like he should, but he doesn't ruin the movie either. Still, his style of "wannabe Brando" subtle acting doesn't really mix with the theatrical nature of a high-energy musical like "West Side Story." Fortunately, Elgort fares much better when paired with actors who raise his energy level. "West Side Story" marks the film debut of Rachel Zegler, and she's exceptional as Maria — a young woman who won't let love pass her by, even if her family disapproves. Their duet of "Tonight" is swoon-worthy.

Unfortunately, one of the film's weaker scenes comes in the form of Tony and Maria's subsequent date the next day. When Tony pours his heart out about once nearly beating another boy to death, Elgort's acting lacks soulful remorse — or, really, any emotion at all. Nevertheless, it's a crucial scene that sets up one of the film's biggest changes from the original, during the rumble.

The gun: mutually assured destruction

One of the biggest changes in the film from the 1961 version is the path of the gun that's ultimately used to kill Tony. In the 1961 movie, Chino just kind of has the revolver, and it doesn't appear onscreen until he uses it in the last several minutes of the story. Here, the gun is purchased by Riff and the Jets to make sure they have their bases covered in case the Sharks bring a gun. The shopkeeper from whom they purchase the gun draws a parallel between their gun and the omnipresent danger (especially in 1957) of nuclear annihilation. Riff thinks he's buying a "deterrent," but the seller makes reference to "mutually assured destruction." Deterrence is the idea that if both sides build up enough of an armory, each side might be too intimidated to escalate violence against each other ... but mutually assured destruction is the notion that they could just as easily wipe each other out for good with their so-called deterrents.

During the rumble, Riff gives Tony the gun, "just in case," but it's discarded during the battle. While the gang members flee from the carnage they unleashed, Chino sees the six-shooter lying on the ground and picks it up, setting the stage for the film's final, tragic showdown.

'Cool'

Between the original Broadway show, the 1961 movie, and now the 2021 version, the song, "Cool," is used differently across all three versions. Originally, it was sung by Riff to keep the other Jets calm in the lead up to the rumble. In the first film, it is sung by the remnants of the Jets after the death of their leader in said rumble. This time, it is sung by Tony as he tries to get Riff to surrender his gun and keep the rumble from escalating into a war.

While Ansel Elgort is an inconsistent presence throughout the film, Mike Faist is absolutely perfect as Riff. While he lacks Russ Tamblyn's gymnastic dexterity from the 1961 movie, his singing, acting, and dancing are all fantastic. Most importantly, his natural chemistry with Elgort elevate their scenes together, preventing Tony from fading into the background as Elgort has no choice but to keep up with Faist's energy level. As a result, "Cool" is one of the best scenes in the movie, since it features a brand new scenario between the two best friends as they dance/fight over the gun that will ultimately spell Tony's doom. It's exciting, tragic, and the dilapidated boardwalk setting adds an extra visual flourish to the moment.

The Rumble

In all versions of "West Side Story," the rumble ends the same way: With Bernardo and Mercutio (the musical's analogues to Tybalt and Mercutio, respectively) dead on the floor after Tony tries in vain to prevent the fighting. This time around, there are some twists to the proceedings, with Tony slicing off a bigger piece of the action than before.

Usually, the climactic fight between Riff and Bernardo kicks off when the latter insults and hits Tony, who is only trying to stop the fighting. This time, Tony doesn't stick to his pacifist intentions, and when Bernardo goads him, he puts up his dukes and engages the Shark in one-on-one combat. Tony wins the fight, and the victory is all the more impressive since this version of Bernardo is a trained boxer. However, before delivering the finishing blow on a subdued Bernardo, Tony is reminded of the boy he beat nearly to death and how he might do the same — or worse — to Bernardo, and stops the fight.

Unfortunately, this leaves an enraged Bernardo to whip out a switch blade and rush the erstwhile Jet leader with a renewed vigor, at which point Riff steps in with a blade of his own. From here, things play as expected, with Bernardo accidentally killing Riff, and Tony killing Bernardo in retaliation.

'I Feel Pretty'

After the rumble, Maria is shown working at the Gimbels department store, eager to see Tony again — especially because she naively believes he was able to defuse the tensions between the two gangs. She doesn't know that he failed and killed her brother, Bernardo. In her unwitting ignorance, she breaks into song and sings "I Feel Pretty," a beautiful solo number about being young and in love, with the rest of the world just melting away.

In the 1961 movie, the song is moved up in the story, placed before the rumble. It's likely the decision was made either to keep the tone from getting too light so soon after the rumble, or to spare Maria from destiny's cruel joke. But with the new movie restoring "I Feel Pretty" to its place from the original show, it adds an extra layer of bittersweet tragedy to the song. Maria's life has been changed forever, and it's about to get even worse, but she doesn't know it yet. This way, when she finds out the truth from Chino, the revelation is even more heartbreaking.

'Somewhere'

Rita Moreno, who played Anita in the 1961 movie, returns for the remake as an actor and Executive Producer, this time playing a new character, Valentina. She's the wife of Doc, the owner of the drug store where Tony works, and effectively takes his place in the narrative. As a Puerto Rican woman married to a white man, she has a unique perspective on the events that unfold, and she sees the budding love between Tony and Maria as something that, while fraught with danger, could bring peace to the dueling gangs.

When she learns of the deadly rumble, Valentina is devastated. She knows firsthand of the potential of love, but she also knows that hate can be such an overwhelming force. As she looks at pictures of herself and her husband, Doc, she breaks into "Somewhere," one of the most beautiful songs from the musical. The song laments the hatred and violence that surrounds Tony and Maria, but with Valentina singing it, it becomes an anthem for interracial love. Valentina and Doc surely had their own "West Side Story," and they were lucky enough to make it through with their lives and their love intact. Tony and Maria would not have the same good fortune.

Chino's rage

Chino is something of a non-entity in previous versions of "West Side Story." He's in something of an arranged marriage to Maria, but she's not interested in him romantically — though she has no personal grudge against him. He's the one who tells Maria that Tony killed Bernardo, and then shows up again at the end to shoot Tony. He's more of a plot device than an actual character.

The new movie give purpose to Chino, with more care and attention paid to his characterization and motives. Actor Josh Andrés Rivera imbues Chino with a sheepish charm. He appears more prominently in many scenes, such as the dance, where he shows off his less-than-impressive, but nonetheless adorable, dance moves. After the rumble, Chino picks up Riff's gun and runs off alongside the rest of the Sharks. He is the focal point of a new scene where he laments the death of Bernardo, his best friend. While the other Sharks wish for a full-scale war against the Jets, Chino decries their selfish pride and calls his dead friend a fool who allowed his own pride to drag him into an early grave. Nevertheless, he sets out to avenge his fallen friend, knowing full well such an act will cost him his soul in the eyes of God, and his freedom when the cops catch him. He's aware of his pride, but he can't escape it.

The ending

After Maria and Anita reconcile, or at least reach an understanding, Anita goes to Doc and Valentina's drug store to tell Tony to wait for Maria to arrive so they can run away together. But when Anita arrives, she is accosted by the Jets, who have become an angry, ravenous mob of young monsters who attempt to sexually assault her. Valentina rescues her and shames the Jets into disbanding, with one member lamenting, "We're done." Alas, the damage is already done, and Anita calls Valentina a race traitor before lying that Chino has killed Maria.

When Valentina tells Tony, he loses control and runs into the night, begging for Chino to finish him, too. Elgort's acting in this scene lacks the gut-wrenching pain of Richard Beymer from the original, which undercuts his relief when he sees Maria, who has finally made it to Doc's. In the 1961 movie, the sight of Maria is enough to snap him out of his stupor, a moment that is present, but somewhat lessened in the new movie.

Still, even the most ardent detractors of Elgort's acting would be hard-pressed not to shed a tear when Chino shoots Tony as Maria helplessly watches. After Tony dies in Maria's arms, Maria snatches the gun from Chino's hands and threatens to shoot him, the Jets and Sharks, and herself, because "I can kill, too, because now I have hate!" It's a brutal declaration, and Rachel Zegler's intensity matches that of Natalie Wood from the original film. Moved by her words and finally understanding the consequences of their actions, members of both gangs respectfully carry Tony's body away while the cops arrive to arrest Chino.

Suffice to say, it's not a happy ending, and Maria's survival deprives "West Side Story" of the conclusiveness of "Romeo & Juliet," since the Jets and Sharks must now live forever with the knowledge that their petty hatred destroyed a love that had the potential to be more powerful than any street gang.