The Untold Truth Of Alien

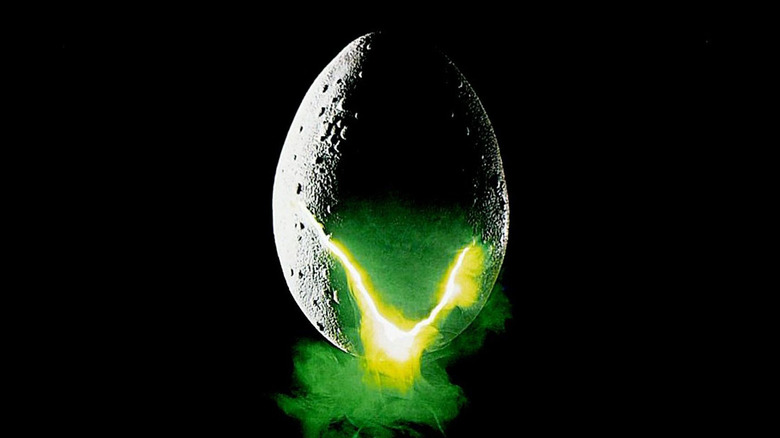

With a list of conflicting influences almost as long as its credits, Ridley Scott's "Alien" is a sci-fi/horror classic—and a balance of volatile components, shaped as by extraterrestrial technomancy into something more frightening than the sum of its parts.

Everybody who worked on the original film as well as the many sequels, prequels, and "Predator" crossover films has had their own idea of what "Alien" is about. Perhaps that's why scholars, sci-fi nerds, cinema aficionados, and film critics alike continue to discover creepy, unexplored channels within this terrifying masterpiece and its "children." Here's the untold truth of the "Alien" franchise, from the birth of the original concept that would become Ridley Scott and Dan O'Bannon's "Alien" to Fede Àlvarez's "Alien: Romulus."

John Carpenter's Dark Star

It all started when John Carpenter approached Dan O'Bannon after a screening of O'Bannon's USC student project "Blood Bath," a seven-minute horror-suspense film about a man who kills himself. (For the curious, "Blood Bath" was anthologized along with other student films by Carpenter, Terry Winkless, Alec Lorimore, and Charles Adair in 2014's "Shock Value: The Movie.") The two set out to make a science fiction movie for Carpenter's master's thesis, which would become the 1974 sci-fi comedy "Dark Star."

O'Bannon was the film's co-writer, editor, special effects supervisor, and production designer, in addition to playing Sgt. Pinback. He also brought irreverent cartoonist Ron Cobb onto the project as part of the special effects team. Ronald Shusett, who would later be credited as co-creator of "Alien," volunteered as editor. Jack H. Harris offered to distribute the movie if Carpenter and O'Bannon would expand it from the planned 20 minutes to feature length, and they agreed.

"Instead of the most impressive student film ever made we had the least impressive professional film ever made," lamented O'Bannon in an interview. Following Dark Star's mixed reception, O'Bannon wanted to do "'Dark Star' as a horror movie instead of a comedy." "While we were in the midst of doing 'Dark Star,'" O'Bannon told Fantastic Films in 1979, "I had a secondary thought on it—same movie, but in a completely different light." He started work on a screenplay called "Star Beast."

You can't always get away with plagiarizing your own ideas, but fortunately, "Dark Star" was such a flop that there was a minimal risk of anyone connecting it to the new project. According to Strange Shapes, after Carpenter and O'Bannon asked to peek in at the audience at a screening, the usher responded, "What audience?" Not many people saw "Dark Star," but future "Alien" director Ridley Scott did — along with visionary filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky — and it left a lasting impression.

Jodorowsky, in fact, was so impressed that he made a late-night phone call to O'Bannon, saying he'd acquired the rights to Frank Herbert's space opera "Dune." With an incomplete "Star Beast" script, no real prospects, and an admiration for Jodorowsky's "El Topo," O'Bannon sold his belongings and moved to Paris to make Jodorowsky's "Dune."

No Alejandro Jodorowsky, no Alien

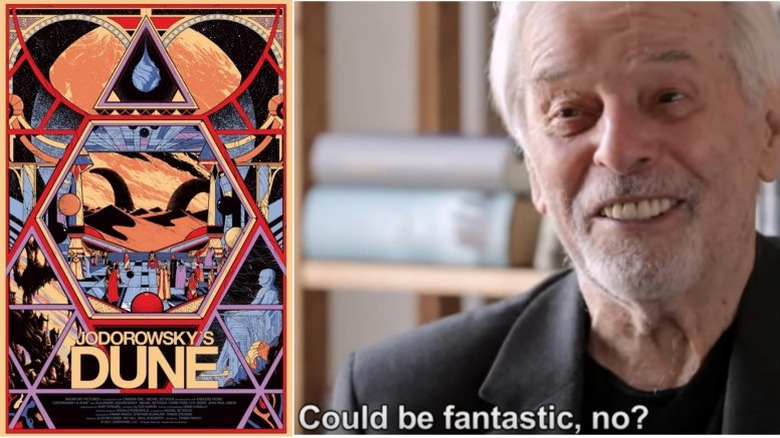

Alejandro Jodorowsky's "Dune," not to be confused with David Lynch's "Dune," is recognized today as perhaps "the greatest movie never made." Jodorowsky had hoped it would be an LSD experience without LSD; unfortunately, he found it impossible to raise enough funding. As detailed in the acclaimed 2014 documentary "Jodorowsky's Dune," "Alien" was one of many successful projects that rose from the ashes of Jodorowsky's ill-fated attempt.

In Paris, O'Bannon met artist Christopher Foss, who'd later do design work for "Alien." When he encountered Foss, "for the first time, [he] saw someone whose stuff [he] liked as much as Ron Cobb's stuff." According to O'Bannon, the screenwriter also met future "Alien" designer H.R. Giger "a couple of weeks before ["Dune"] fell through," and the pair quickly discovered they had a lot in common—including a shared appreciation for H. P. Lovecraft.

Jodorowsky's philosophy of art design, based on collaboration and competition, was revolutionary. He would find his "spiritual warriors," as he called his collaborators, and then put them together in one big room. Later, O'Bannon would use the same strategy to brainstorm about "Alien," bringing together Foss, Cobb, Moebius (who worked on storyboarding), and Giger.

In 1975, while working on "Dune," widely respected cartoonist Moebius adapted O'Bannon's short story "The Long Tomorrow" into an influential comedic sci-fi noir comic, published in 1976 in "Metal Hurlant," the French magazine on which "Heavy Metal" magazine would later be based. Ridley Scott's Blade Runner and William Gibson's novel "Neuromancer" cite "The Long Tomorrow" as a major influence. Oh, and George Lucas borrowed a design from it for the probe droid in "The Empire Strikes Back."

Script-related struggles

Ultimately, Brandywine Productions agreed to produce the film for 20th Century Fox. While Scott was focused on staying under budget, there was another serious drama going on. According to O'Bannon, producers David Giler and Walter Hill plotted to steal his writing credit. Giler has publicly disparaged O'Bannon's screenplay, and he and Hill took it upon themselves to correct what they viewed as shortcomings, cooking up a total of eight rewrites. The screen credits would eventually head to arbitration.

According to Giler, the screenplay required such intensive rewrites that he and Hill "[changed] all the dialogue. Every word of it." (A line-by-line comparison between a later Giler-Hill draft and O'Bannon's original suggests Giler is either mistaken or knowingly exaggerating.) Giler credits his work with Hill for "adding the feminist elements everyone is talking about. [Walter Hill and I] gave the characters texture, functions. In O'Bannon's draft, they were totally different, military types. All men."

We were left with four major aliens, and we're not talking about the so-called "Quadrilogy." There's O'Bannon's expansion of his "Star Beast" screenplay, featuring the xenomorph, the space jockey, and the wrecked ship, but also an elaborate pyramid-shaped egg silo megastructure, no androids, no women, and some space truckers with really outlandish names — Standard, Faust, Melkonis, Broussard, and Roby instead of Ripley. Roby?

Hill and Giler's rewrite introduced Ripley and Dallas and the rest of the gang, a vast corporate conspiracy involving human-looking androids, and a big cylindrical silo — but also, in certain drafts, a time-travel-based plotline featuring Jack the Ripper, Hercules, and Genghis Khan, and, in their favorite draft, a human space jockey and no alien! Then there's the "Alien" that, against daunting odds, Scott and his team somehow made despite the squabbling and confusion.

Finally, there's "Alien: The Director's Cut," Scott's definitive version, which bears little resemblance to O'Bannon's vision. "I didn't write 'play it slow,' which is what Ridley did!" complained the screenwriter. "He played it slow and he was damn lucky that slow worked so well." As Foss told Den of Geek, "Poor old Dan O'Bannon, the bloke whose concept it was, just got absolutely shafted."

The Nostromo almost looked very different

Chris Foss and Ron Cobb were essential to the creation of the Nostromo, the spaceship where all the "Alien" action takes place. After O'Bannon returned, broke, to the U.S., he got serious about completing the "Star Beast" script and getting it made. In short order, he procured funding, assembled a team, and tried to recapture the magic of Jodorowsky's method. "For up to five months Chris and I (with Dan supervising) turned out a large amount of artwork, while the producers, Gordon Carroll, Walter Hill and David Giler, looked for a director," Cobb recalled.

Of course, the problem with adapting an anarchic creative philosophy is that O'Bannon's style was, by Ron Cobb's account, not at all conducive to letting the artists figure things out. "[Dan determined] that I would tackle the interiors of the earth ship Nostromo, while Chris would design the exterior," he continued. "It didn't take long for this [arbitrary] division of labour to become a bit problematic... " O'Bannon had a reputation for being difficult to work with, dating back to his Dark Star days.

In Foss's recollection, O'Bannon looms large. "I was happily beavering away on my designs, and Dan, of course, was practically standing over me... and it all came to nought." His dazzling, spaced-out illustrations ended up in art books, with the producers choosing to use one of Cobb's external designs for the Nostromo. That said, it's obviously Foss-influenced, however grounded in Cobb's "form follows function" philosophy.

Cobb's admiration for Foss is palpable. We can only speculate on what "Alien" would've been if one of Foss' "endless spacecraft designs suggesting submarines, diesel locomotives, Mayan interceptors, Mississippi river boats, [and] jumbo space arks" had been used for the Nostromo, but it seems they were simply too outlandish for the money people's taste.

David Cronenberg cries foul

According to Foss, O'Bannon wrote the chestburster scene following a particularly painful bout of indigestion related to Crohn's disease. O'Bannon "imagined that there was a 'beast' inside him. And that [experience] was exactly where ['Alien's' chestburster] came from." Giger claimed the inspiration was actually O'Bannon imagining the pain bursting out of him and leaving his body. Plausible as Foss and Giger's explanations are, one high-profile writer-director rejects it, crying plagiarism.

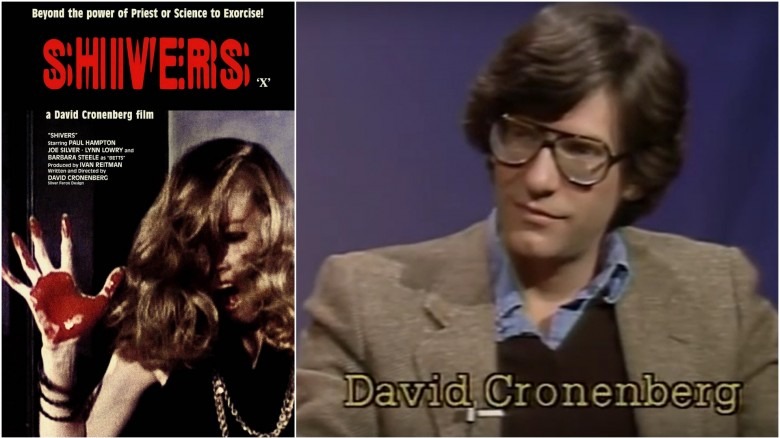

Acknowledging that subtler forms of imitation can be flattering, David Cronenberg takes issue with the xenomorph's similarities to the parasite in his 1975 "body horror" movie "Shivers," first released in the U.S. as "They Came from Within." Based on the awesomely named shooting script "Orgy of the Blood Parasites," Shivers is about "a parasite that lives in you and burns its way out of your body and...jumps on your face and goes down your throat." That could describe the xenomorph in "Alien," but we'd need a little more.

Cronenberg's source regarding the allegations is director John Landis, but Landis's only on-record beef with the xenomorph is with the absurdity of the mouth on its tongue. Nowhere in Giger's designs, the mouth was added by creature effects artist Carlo Rambaldi.

"['Alien'] was more popular than any of [my movies]," the creator of "Shivers" admits. If getting his name in the credits is indeed his goal, as he's said, then maybe he shouldn't also say things like "'Alien' was just a $300,000 B-movie with a $10 million budget." He should probably quit likening Giger's xenomorph to "a man in a crocodile suit who chases a bunch of people around a room," too. Seriously, has Cronenberg ever seen a crocodile?

John Cazale's death impacted the casting

In an alternate universe where John Cazale doesn't get cancer, Meryl Streep stars as Ripley in "Alien." (Perhaps Sigourney Weaver plays the light-hearted version of Lambert from an early draft of the screenplay, a role in which she'd expressed interest.)

Known for his role as Fredo in "The Godfather" and "The Godfather Part II," Cazale appeared in just five Hollywood movies — the other three being "The Conversation," "Dog Day Afternoon," and "The Deer Hunter." Always in a supporting role, Cazale was an "actor's actor." He was also Meryl Streep's romantic partner.

Before Weaver landed the part of Ripley, Streep was on the short list of candidates to be offered the role, but Cazale's 1978 passing derailed those plans. Nobody felt comfortable interrupting her mourning to make the offer.

H.P. Lovecraft would probably see a lot of his work in its take on body horror

Dan O'Bannon called H.P. Lovecraft "the greatest horror writer who ever lived," and certainly, Lovecraft's influence is palpable in O'Bannon's work. Alienness is something to be feared and loathed in Lovecraft's stories — he built a fictional universe around a group of space aliens worshipped as gods by fearful humans.

Like Lovecraft, O'Bannon was morbidly fixated on alienness, body horror, and the grotesque. As fiction writer, critic, and scholar Charles Baxter put it, Lovecraft had "the timid shut-in's phobia of difference, variety, and diversity, with the result that the category of the 'alien' [includes] outer-space creatures, [various ethnic groups] and women."

Lovecraft's most recognizable representative of the terrible unknown is Cthulhu in chains in the submerged ruins of R'lyeh, a character whose imprisonment in the sea is similar to the xenomorph's gestation with in its human host. Cthulhu threatens to break free, breach the surface, and wreak havoc among unsuspecting humans, just like the xenomorph. Lovecraft-inspired horror novelist Stephen King considers Cthulhu to be a nightmarish symbol of angst about sex; O'Bannon and H.R. Giger created the xenomorph in the same disturbing light.

Alien is kind of a big deal in academia

Academia adores "Alien." Media theorists and cultural critics simply can't stop writing about it. There's the demonic parasite who reproduces via indiscriminate facehugging, the indifference of "Mother" to the crew's suffering, Sigourney Weaver's iconic performance as no-nonsense heroine Ellen Ripley, the age-old "are androids people?" dilemma, the secret schemes of a sinister mega-corporation with no regard for the safety of its employees, and so much more. If the grotesque imagery, state-of-the-art special effects (still astounding today), and storied production aren't enough to build a compelling Film Theory thesis, then maybe the feminist undertones, Freudian motifs, and Marxist themes will do the trick.

Attesting to the movie's multifaceted appeal among nerds in high places is the June 2017 book Alien and Philosophy, a collection of essays on all things "Alien." It's heady stuff, but it just goes to show there's more to the xenomorph than a facehugger, a chestburster, and "a man in a crocodile suit."

"Alien's" complexity is the product of the many-headed hydra of personnel who worked on it. The movie changed course repeatedly through rigorous rewrites, O'Bannon's antagonistic relationships with the producers, O'Bannon and Giger's fascination with H.P. Lovecraft, budgetary constraints which effectively scrapped ideas, and a last-minute recasting that brought in John Hurt, whose performance in the "chestburster scene" routinely ranks on lists of best deaths in horror movies.

Carlo Rambaldi's special effects almost sent somebody to jail in Italy

H.R. Giger's designs were one part of the creepy equation, but bringing them to life required the expertise of Carlo Rambaldi, a veteran creature effects artist who was frighteningly good at his work—as director Lucio Fulci knew all too well.

In 1971, Fulci enlisted Rambaldi to provide special effects for his giallo film, "A Lizard in a Woman's Skin." One scene called for the (simulated) mutilation of live dogs, and Rambaldi's effects were so realistic that the Italian courts charged Fulci and the producers with cruelty to animals. They were exonerated only after Rambaldi brought his props into the courtroom and explained how they worked.

There are deleted scenes you might not have heard about

Inevitably, some shots that were filmed for "Alien" didn't make the cut. (In fact, the ending was almost completely different, and much sadder.)

Brett (Harry Dean Stanton) has the bad luck of being pulled up into the elevator shaft, but his death was supposed to be even grislier. He was to be impaled on the alien's tail and have his heart ripped out, or else get his head crushed in the palm of the adult xenomorph's taloned hand and his face eaten. Apparently, many sequences were cut to preserve the "less is more" style that works so well to terrify. Oddly, "only a partial segment of the tail scene survived the editing process and was used during Lambert's death scene," as Scified points out.

Lambert's death is even more haunting because it's completely implied—she's terrified, paralyzed by fear. Her death was filmed for an earlier cut, but it just doesn't work. From the goofy crab-walking alien to the total lack of suspense, it's understandable why this scene ended up on the cutting room floor.

In a scene that's in the director's cut but not the theatrical version, Lambert slaps Ripley. Veronica Cartwright, who played Lambert, was happy to see "they put the hit back in ... Ripley was an [expletive] for not letting [the crew] in."

Sigourney Weaver wanted to play Lambert

Showing just how much the "alien" script changed from day to day, Ripley wasn't Sigourney Weaver's first choice. "Actually the part I wanted to play was Lambert, Veronica Cartwright's part," she admitted in an interview with Danny Peary, anthologized in 1984. "In the first script I read, [Lambert] just cracked jokes the whole time... She didn't crack up until the end." That's night-and-day from the neurotic "sympathetic character" that Lambert eventually became.

According to New Zealand-based NewsHub, Cartwright read for Ripley, even believed she would play Ripley, and learned just prior to the shoot that, in fact, she'd been cast as Lambert. Considering all the hardships that the pre-production team had to deal with, it sounds like Cartwright got a pretty good deal. Then again, according to Cartwright, "I'm in eight of [the nine outtakes included in the 'Alien' box set]. I had a big part in that movie and it was changed."

Hicks was almost played by a completely different actor

Michael Biehn may seem like such a natural fit for Corporal Dwayne Hicks that it's impossible to imagine anyone else playing the character — but he was actually James Cameron's second choice for the role. The part was almost played by James Remar, who had been cast to play Hicks until a drug bust changed that plan.

Remar was in the middle of filming his portion of "Aliens" in London when his apartment was raided by law enforcement, who had been alerted to the actor's hash and heroin usage after taking note of the various individuals who would come by the actor's apartment to "visit." Remar was arrested and subsequently fired from the production.

Cameron filled the role by calling up Biehn, who had played Sgt. Kyle Reese in "The Terminator," salvaging some of Remar's work in long shots and scenes that showed the character from the back. It didn't help Remar's reputation that he had accidentally shot a hole in the wall of one of the film's sets with a prop gun earlier in filming, and the dummy round went right through the "Aliens" set's walls and into those of a set belonging to "Little Shop of Horrors." While Remar recovered and went on to have a solid career as a character actor, he has expressed regret over disappointing those who had helped him get the part of Hicks.

The Alien Queen's behavior was inspired by a specific insect

While the look of the xenomorph queen is obviously based on H.R. Giger's fantastical drawings, her behavior, genesis, and life cycle were decided upon by James Cameron and Ridley Scott. In the end, Cameron actually based the queen's behavior on a real-life insect: the digger wasp.

"In my story, the eggs come from somewhere else. At least that was my theory," Cameron said in the book Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer. "So working from that theory – acres and acres of these quite large eggs, two and a half to three feet tall – I began to focus on the idea of a hierarchical hive structure where the central figure is a giant queen whose role it is to further the species."

He later explained in an interview with the sci-fi magazine Starburst (via Alien Explorations), "One of Alien's great attributes was that it set up a very weird biological process but it has a basis in science fact all the way through like the cycle of a digger wasp which paralyses its prey and injects an egg into the living body to mature." So whenever you see those facehuggers making a leap toward a human head, think of Mr. Cameron and his devotion to scientific reality.

The Space Marines were trained by a real military man

Have you ever wondered how the Space Marines were whipped into shape and prepared for combat? It turns out one of them had previous real-life combat expertise and lent a helping hand to make the corps' marching as authentic as possible. Al Matthews, a Vietnam veteran who served with the real Marines and plays Sergeant Apone in the film, was also enlisted to teach the squadron how to act like actual soldiers.

"Jim (Cameron) asked me to train them, and the main thing I had to teach those guys was never point a weapon at somebody, and never walk around with your finger on the trigger," Matthews told Empire Magazine in 2009 (via Flexible Head). "We use blanks, but they can do some damage." Matthews was definitely the right man for the task, as he had two Purple Hearts to his name in addition to having earned eleven other decorations and awards during his time in the military.

James Cameron hated the beginning of Alien 3

James Cameron definitely isn't alone in hating the beginning of "Alien 3," where Newt (Carrie Henn), Bishop (Lance Henriksen) and Hicks are famously killed offscreen, leaving Ellen Ripley alone and in a hostile situation. In fact, he was quite vocal about how much he hated the way the film begins.

"I thought [killing off Newt, Hicks, and Bishop] was dumb. I thought it was a huge slap in the face to the fans," Cameron said at the 2016 International Comic-Con (via The Playlist). But, interestingly, he doesn't blame the film's director. "David Fincher is a friend of mine, and he's an amazing filmmaker, unquestionably," Cameron added. "That was kind of his first big gig, and he was getting vectored around by the studio, and he dropped into the production late, and they had a horrible script, and they were re-writing it on the fly. It was just a mess. I think it was a big mistake." But despite defending his friend, Cameron made it clear that he never would have made the same choices if he were at the helm.

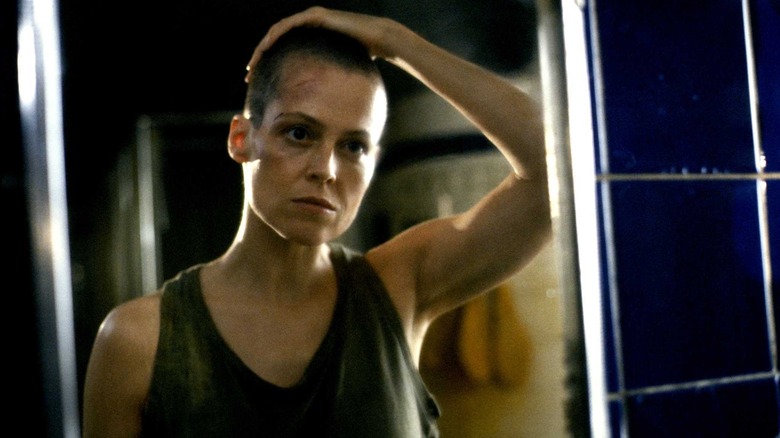

Sigourney Weaver was paid extra to shave her head

In the extremely dark world of "Alien 3," Ellen Ripley must shave her head to comply with the standards of the prison planet Fiorina "Fury" 161, where she has crash-landed, because a lice outbreak has occurred. It turns out Sigourney Weaver might have landed a big payday for going bald; she was reportedly paid $4 million as a base sum to shave her dome for Ripley's long, dark journey into the night.

When principal photography was completed, Weaver moved on to other films and wore a wig while her hair grew back. Unfortunately, the embattled shoot required even more scenes to be re-filmed, forcing her to shave her head again and lose any progress toward her natural hair's return. Thanks to a clause in her contract, she earned a bonus of $300,000 for cropping her locks one more time so they could complete the movie. All in all, not a bad chunk of change for a temporary cosmetic tweak. What's more, Weaver admitted she liked it once it was gone. "It was quite a great haircut. I kind of miss it," she told The New York Times.

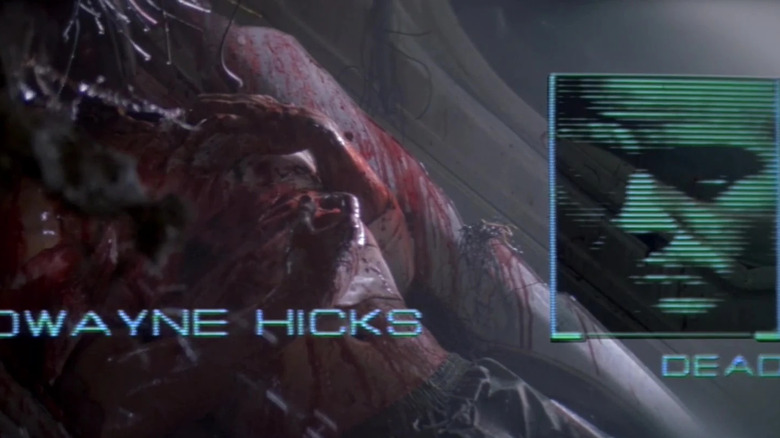

Michael Biehn was actually paid not to be in Alien 3

It's rare that an actor gets paid to stay out of a production, but Michael Biehn was paid actual cash to not appear in "Alien 3." Call it the benefit of having good friends, eagle eyes, and reps who aren't afraid to enforce the limits of a contract.

Biehn learned through the grapevine that a face cast of his visage that had been made for "Aliens" was used to create a dummy to shoot a scene in which a chestburster explodes from Hicks' torso. Suffice it to say, the actor was not happy. "I called my agent up and he called up Fox and said, 'You can't use Michael's image.' They said, 'Okay, we'll get back to you,'" he recounted to Ain't It Cool News. "I got a call from David Fincher saying 'Please, can we just... We'd really like to use your character.' And first of all I was like 'F**k you for not putting me in the movie."

He also nixed Hicks' death by chestburster, so the studio negotiated to use a grainy image of Biehn as Hicks, which is briefly shown onscreen during the finished film — something Biehn was fine with if he got paid.

Sigourney Weaver actually made that trick basketball shot in Alien: Resurrection

"Alien: Resurrection" sees Ripley 8, a clone of Ellen Ripley, coping with life among space pirates. It turns out her existence is partially due to an experimental attempt to breed xenomorphs that might be useful to human life. Unfortunately, as Ripley predicts, chaos breaks loose. But before then, she manages to beat the entire crew in a game of basketball, sinking her final shot through the hoop by tossing it back over her head without looking.

It turns out Sigourney Weaver actually successfully made the trick shot all by herself, even though director Jean-Pierre Jeunet was prepared to bring in a double, per a production diary written by the actor. She practiced for two weeks to pull off the moment, and "by the time we are ready to shoot, my average on the shot is one basket for every six tries," she said (via Den of Geek). Though urban legends have persisted that Weaver made the shot (which Jenet decided to make even longer and thus more impressive-looking) on her first try, it actually took three tries to make the basket — but the end result so impressed actor Ron Perlman that he couldn't hide his expletive-filled reaction, which had to be edited out of the film.

Alien: Resurrection was set to follow a clone of Newt

While "Alien: Resurrection" ended up following a clone of Ripley, the original plan was to follow a clone of Rebecca "Newt" Jorden. After Sigourney Weaver declared herself completely done with the "Alien" franchise once "Alien 3" wrapped, the studio's solution was to build a film about Newt, or so former 20th Century Fox executive Jorge Saralegui explained in an interview with Starburst Magazine (via AVP Galaxy). "We had the notion of having Newt cloned [...] The people at Fox liked the idea enough to say 'Okay, why don't you start working on it and find a writer?' The first and only person I thought of was Joss Whedon."

Under Whedon, the film evolved into a story of an older Newt clone being engineered and then set on Ripley's trail. After the movie was greenlit, however, that evolved into a thirty-page treatment where Newt instead hunts for xenomorph samples. But no matter how excited Whedon and Saralegui were for the idea, 20th Century Fox balked at the notion of doing another "Alien" movie without Weaver. They ended up offering her millions to return, Whedon was sent back to the drawing board, and Newt has remained dead ever since.

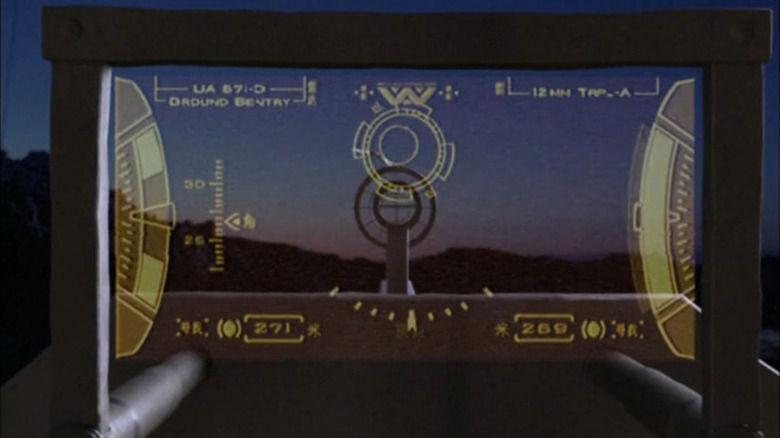

An Easter egg ties Firefly and the Alien universes together

The Whedonverse is, obviously, pretty solidly connected to the "Alien" world. But fans of Whedon's science-fiction series "Firefly" might not have noticed that it's got a subtle Easter egg that pops up in the pilot episode that binds the two universes together all the more firmly.

Take a close look at the heads-up display that flashes onto the screen when Malcolm "Mal" Reynolds (Nathan Fillion) picks up a large gun to fire during the Battle of Serenity Valley. At the top center of the screen, the logo for the Weyland-Yutani Corporation is briefly visible, a reference to the "Alien" franchise's corporation that's nearly exclusively dedicated to making life in the galaxy worse for everyone. A nice little reference and, even more importantly, proof that the universes coexist.

Prometheus was intended to be a direct Alien prequel

Originally, "Prometheus" was designed as a direct sequel to the "Alien" world rather than a prequel. In its embryonic stages, it was titled "Alien: Engineers" — which, naturally, is the white-skinned race featured in the finished film, the architect of the future downfall of humanity. There's no word as to how different this script might have been, but 20th Century Fox decided to take the movie in a different direction, severing many of its direct ties to the "Alien" universe.

Damon Lindelof reworked the script on Ridley Scott's behalf, turning it into a deeper origin story that parallels the tale of Prometheus, who, in Greek mythology, gifts humanity with fire stolen from Mount Olympus. As a result of the retooling, outside of the way it uses xenomorphs and spins a possible origin story for them, there's little connection between "Prometheus," "Covenant," and the main "Alien" series.

Tennessee takes direct inspiration from a famous comedy

Danny McBride's Tennessee bears his distinctive character and attitude in "Alien: Covenant" for an important reason. He's obviously reminiscent of Dallas, captain of the Nostromo in "Alien." But it seems he was also inspired by a completely different movie character — Slim Pickens' Major T. J. "King" Kong from "Dr. Strangelove." The idea mainly came from director Ridley Scott, who explained to McBride that the characters in every "Alien" film are typically whittled down to a certain sort of stereotype due to their tendency to become xenomorph fodder.

"He said he saw Tennessee as an homage to the character Slim Pickens played in 'Dr. Strangelove'"—a Southerner, and something of a child, but not an a******," McBride told The New Yorker. Since Tennessee, unlike Major Kong, lives to fight another day by the time "Covenant" comes to a conclusion, that's quite an interesting bit of source material.

Guillermo Del Toro almost directed Alien vs Predator

Guillermo del Toro is an expert at combining whimsy, dark fantasy, and truly gory and horrifying character designs. This is probably why he was offered "Alien vs. Predator." But he turned it down to make "Hellboy" — a wise decision, as any fan of del Toro's work would tell you. Apparently, he was also in the running for "AVP: Requiem," but, if it was ever in the actual offing for him, he also turned down that assignment.

Producer Jorge Saralegui was reportedly very high on using del Toro, who he was close with, for "Alien: Resurrection," but 20th Century Fox wouldn't bite. In an interview with Alien vs Predator Galaxy, Saralegui said, "It would have been interesting, because it would have been expensive [..] Guillermo doesn't cut corners. But it would have been great." Interestingly, del Toro also turned down directing two "Harry Potter" films to make his "Hellboy" duology — "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban" and "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince."

Arnold Schwarzenegger was offered a cameo in Alien vs Predator

Fans have been highly critical of the "Alien vs. Predator" series of films for quite a while, but 20th Century Fox did try to do something right with the franchise — get Arnold Schwarzenegger to appear in the crossover franchise as his legendary "Predator" hero, Dutch Schaefer. Unfortunately, the timing never worked out for Dutch to return either in "AvP" or his original franchise despite four attempts being made to add Dutch to various "Predator" sequels, be it in a cameo, supporting, or leading capacity.

In the case of "Alien vs. Predator," Schwarzenegger was offered a cameo and agreed to show up if he lost his first run for the office of the governor of California. Apparently, the Governator was never offered a role in "Requiem" — and judging from both audience and critical reactions to that outing, he probably considers himself lucky.

Ridley Scott and James Cameron claimed AVP ruined their changes for an alien sequel

James Cameron has never been keen about any of the "Alien" sequels, but both he and Ridley Scott were upset that the existence of the "Alien vs. Predator" duology — specifically the financial failure of "AVP: Requiem" — meant that their planned "Alien" sequel had to go out the window.

"I think Alien vs. Predator was a daft idea. And I'm not sure it did very well or not, I don't know. But it somehow brought down the beast," Scott told The Hollywood Reporter. Cameron agreed, saying during a Reddit AMA, "Fox went ahead with Aliens vs. Predator and I said, 'I really don't recommend that, you'll ruin the franchise, it's like Universal doing Dracula versus The Werewolf, and then I lost interest in doing an Alien film."

Despite this, Cameron has continued to express a desire to rectify what "Alien 3" did to the characters from "Aliens," but it remains up in the air as to whether or not he or Scott will ever get that chance.

A deleted scene from Aliens inspired the creation for Romulus

Fede Àlvarez is a major horror veteran, and when he was given the chance to create his own "Alien" film, he took inspiration from a deleted scene axed from "Aliens." He noted a bunch of kids running around the space colony, thought about Weyland-Yutani's unscrupulous practices, and decided to make a movie about what it's like to be stuck in space as a young adult.

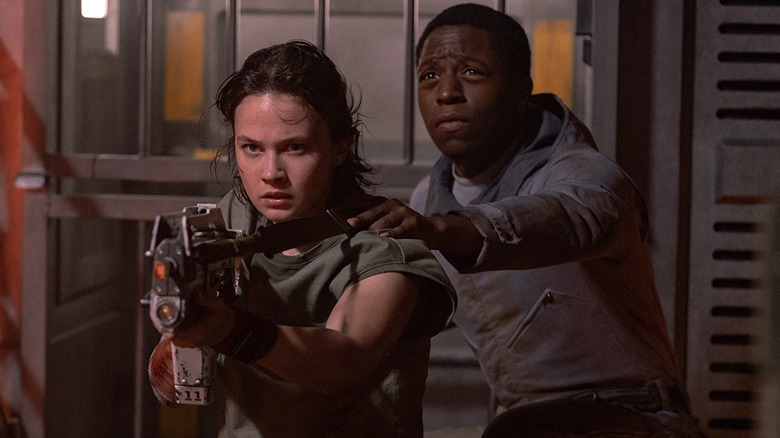

"Once they're in their teens and 20s, they're going to rebel," Alvarez said on Q with Tom Power (via the CBC). "No one's going to be on a planet for 50 years [that] has nothing for you but being a miner or a farmer." He noted that this is a common form of rebellion for most people, who seek new places as they grow. And thus the adventures of Rain (Cailee Spaeny) and her compatriots were born. And, as the box office haul for "Alien: Romulus" proved, audiences were there for it.

The movie's CGI resurrection of Ian Holm was so bad it was fixed for steaming

There was one thing no one seemed to like about the otherwise well-reviewed and audience-approved "Alien: Romulus," and that's the fact that the late Ian Holm, who played Ash in "Alien," had his likeness recreated so he could "play" a new android named Rook. The end result was roundly drubbed by critics and viewers alike due to its poor quality, in spite of the fact that it was produced largely via practical effects and puppetry. Fede Àlvarez took note of thes negative comments and then did something about them.

"We fixed it," Àlvarez told Empire Magazine (via Variety). "We made it better for the release right now. I convinced the studio we need to spend the money and make sure we give the companies that were involved in making it the proper time to finish it and do it right. It's so much better." He later admitted he wasn't happy with the quality of the shots either and felt they were rushed. The end result is an updated version of the film that ended up pleasing most fans.