Biggest Mistakes House Of The Dragon Can Avoid

After several attempts at a spinoff prequel never got off the ground, "Game of Thrones" fanatics got some good news recently when filming resumed on the prequel series "House of the Dragon" after a positive COVID test on set. But even the most die-hard fans of the show have to be wondering if the new series, set hundreds of years before the events of "Game of Thrones," will fall victim to the now infamous mistakes of the original.

Even though the first six seasons of the show were largely praised by critics and beloved by viewers, the shortened final two seasons made so many mistakes that the words "Game of Thrones" now prompt conversations about what a missed opportunity it was, instead of it being a landmark achievement for fantasy television. Here are some of those mistakes, ones that "House of the Dragon" would be wise to avoid.

Avoid "sexposition"

A common tip for writers in any medium is "show, don't tell." In short, you want to avoid exposition dumps where characters explain their histories and motivations out loud, because it slows down the narrative and feels artificial. The writers of "Game of Thrones," presented with a vast amount of information from the books they needed to get across to viewers, were unable to avoid many such scenes where characters just tell each other this sort of information, so they split the difference and showed a whole lot of nudity to spice it up.

Critics coined the portmanteau "sexposition" to refer to this phenomenon, and rightfully pointed out that in addition to not really solving the "show don't tell" problem, the nudity was often gratuitous and served no storytelling purpose for the characters involved. Sex worker Ros ended up involved in three different versions of the same scene, having to listen to Tyrion Lannister, Theon Greyjoy, and Petyr Baelish go on and on about their family histories and motivations while she was just trying to get through a day's work.

Instead of distracting viewers, sexposition was just a way for "Game of Thrones" to be lazy in two ways at the same time, whereas "House of the Dragon" has an opportunity to be more thoughtful and fluid from the beginning.

Don't rely on flagrant sexual violence and assault

This point has been made many of times, but "Game of Thrones" had a real sexual assault problem. George R. R. Martin's books, and the show adapted from them, allegedly sought to portray a way of life accurate to that of this world's Middle Ages, which were certainly cruel times to be alive.

But in the last several years, a real reckoning has taken place with the way we depict sexual assault and the treatment of women in stories and on screen. How much needs to be shown to achieve the artistic effect you're looking for, and how do you stop short of unwittingly glorifying it? This conversation was reflected in "Game of Thrones" criticism for its over-reliance on it, as a small chorus of detractors bothered by Daenerys being sold as property in the pilot grew to a roar by the time the same fate befell Sansa in Season 5.

It's a delicate balance, and one that "House of the Dragon" would be best served to avoid as much as possible. Even though the Targaryens on the whole had some particularly shocking customs from a modern perspective, it's easy to imply events and focus instead on the psychological effects of such treatment in the service of character, rather than gratuity.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Avoid needlessly graphic violence

Not to keep sounding like a scold, but a little off-screen violence goes a long way. Remember the cop getting his ear cut off in "Reservoir Dogs"? Everyone does, because it was horrifying, impactful — and none of it was seen on screen.

No one expects a "Game of Thrones" spinoff to concern itself with the intricacies of successful diplomacy, of course, but there's a difference between depicting the brutality of war and lingering closeups of torture and gore. For 8 seasons, "Game of Thrones" walked the line between the violence that viewers expected of any good swords and sorcery epic, and just plain cruelty for cruelty's sake in its choices. This applied to the choice of acts shown on screen (like the pregnant Talisa Stark being stabbed repeatedly in the belly) or just off screen (like the burning of the young Shireen Baratheon).

"House of the Dragon" may be tempted to push the boundaries even further — after all, it's adapted from a book called "Fire & Blood." But it would do well not to rely on senseless, constant acts of extreme violence, because eventually that either drives viewers away or creates viewers who become harder and harder to truly impact unless you just keep escalating.

Commit to consistent travel times

Maybe "House of the Dragon" can settle something once and for all: How long does it take to get around Westeros? In early seasons, we spent multiple episodes with the Stark family as they made the weeks-long journey from Winterfell to King's Landing. The travels of Arya and the Hound, or Jamie and Brienne seemed to last entire months. But by the last two seasons, characters were popping up everywhere with little to no warning. At one point, Varys is seen in Dorne and then across the sea in Mereen in the same episode. Did he teleport?

Defenders of the show say the pacing and timeline merely adjusted to the much busier plot of the later years, but that doesn't explain the episode "Beyond the Wall," when Gendry sent a raven from the Wall to Daenerys at Dragonstone, who then flew to the rescue, all in the span of one day. Director Alan Taylor even admitted to Variety in 2017: "We were aware that timing was getting a little hazy."

As "House of the Dragon" will be focused on Targaryens entrenched in power at King's Landing, well before the events of "Game of Thrones," it will perhaps be a little less travel-centric. But even though many major characters will have dragons, it would behoove the show to be consistent. Even just in its opening credits, the vast sprawl of Westeros was an important part of the appeal of "Game of Thrones," the physical distance made it feel like a whole world we were discovering. If the spinoff can find a reasonable way to depict how long it takes to get around, it could avoid another distraction it doesn't need.

Avoid incoherent character development

It's hard to rank the most disappointing things about the end of "Game of Thrones." Opinions might differ on the particulars of the plot, like who ended up on the throne, the fate of the white walkers, and so on. But one thing all fans agreed on is that too many characters made abrupt, maddening decisions that weren't earned by the storytelling thus far.

The biggest example was Daenerys Targaryen's snap decision to become a murderous tyrant, although one could argue that the seeds were always planted for this reversal and it was just badly executed. But many characters seemed lost as soon as the showrunners ran out of source material from the books. Tyrion went from a cunning, ruthless schemer for the first five years of the show to Daenerys Targaryen's rather useless Hand, ineffectually worrying as he made blunders and couldn't stop her descent into madness. His brother Jamie seemingly evolved from a villain to a more righteous, caring individual — only to throw it all away and go back to his sister. Even the decision to make Bran the king came completely from left field, as nothing in his story foregrounded any yearn for leadership, or a destiny beyond becoming the mystical seer known as the "Three Eyed Raven."

"House of the Dragon" has an opportunity that "Game of Thrones" did not: Since it's set hundreds of years before the events of its predecessor, it is already known where each character starts and ends up, in a broad sense. So the writers and showrunners should feel freed, able to concentrate on giving each of them consistent traits that evolve through cumulative, lasting changes.

Focus on the journey, not the destination

The early success of "Game of Thrones" only seemed like it was due to the plot. Sudden deaths, surprising twists and turns, these are hallmarks of many great shows. But as the last two seasons reminded us, a dense plot can be as much a burden as a blessing.

So much had to happen, in such a condensed amount of episodes, that it made it clear the real appeal of the show in the earlier years was its deep cast and patient storytelling. Characters went on journeys and developed relationships despite deep-seated resentments and gruff exteriors. Plot twists had real suspense to them because they had buildup, and happened to characters that spoke to each other with subtext and emotional inflection that seemed true to life. By the end of "Game of Thrones," it was an entirely different show where the characters spoke stiffly and exposition-heavy at nearly all times, as if they were narrating the "previously on" segment instead of living their lives.

Let that be a lesson to "House of the Dragon" — in the age of intense internet scrutiny, episode recaps and trending twitter topics, you're not going to satisfy everyone no matter what happens in the plot of your show. So make sure the experience is vivid, true to the characters, and has enough room to breathe.

Respect the source material

In terms of source material, "House of the Dragon" will be on completely different footing than "Game of Thrones." Instead of five entire novels and a conspicuously-missing final two volumes, the showrunners of "House of the Dragon" will be adapting only about 60,000 words of Martin's "Fire & Blood." So they'll have a much smaller amount to adapt, in one sense, but at least a concrete story to adapt with a known ending, in terms of who ends up in power and who lives or dies.

In any case, they should learn from "Game of Thrones" and show a little more respect for the text. Many of the biggest problems with the show's endgame were borne from small differences that had a snowball effect. The character Tyrion allies himself with, Aegon Targaryen, didn't exist in the show, so he became a passive advisor to Daenerys instead. Beric Dondarrion dies in the books semi-resurrecting Lady Catelyn Stark, who becomes the wraithlike Lady Stoneheart — in the show, none of that happens and he dies in an anticlimactic manner much later in Season 8. Television is obviously its own medium, and changes are inevitable to a degree, but "House of the Dragon" needs to have clear, deliberate purpose in making its changes.

Lighten it up a little bit

Granted this complaint is mostly about a single episode of "Game of Thrones," but it was a universal one. After a series-long buildup to the epic battle with the undead in "The Long Night," it was too dark to see! Viewers could hardly make out the show's only dragon vs dragon sky battle, and had trouble telling who lived or died during the dimly lit chaos for much of the episode. Cinematographer Fabian Wagner was even forced to defend the episode to TMZ, claiming that the show "has always been very dark and a very cinematic show," and recommended that fans turn off all the lights in their room to help.

It was one of the most memorable disappointments of the show, especially after the earlier seasons often avoided giant battle scenes when the budget was lower. So hey, "House of the Dragon": maybe have your characters wait until sunrise for any epic, climactic showdowns that are essential to your story.

Keep all seasons the same length

The length of the first six seasons of "Game of Thrones," at ten episodes apiece, could be considered too short for the amount of story they had to tell. But by all accounts, showrunners David Benioff and D. B. Weiss did a laudable job balancing multiple plot threads spread out over dozens of main characters, all further separated by vast distances, to tell a compelling, coherent story to that point. The show became such a massive success, in fact, that HBO would have seemingly been willing to keep it going forever.

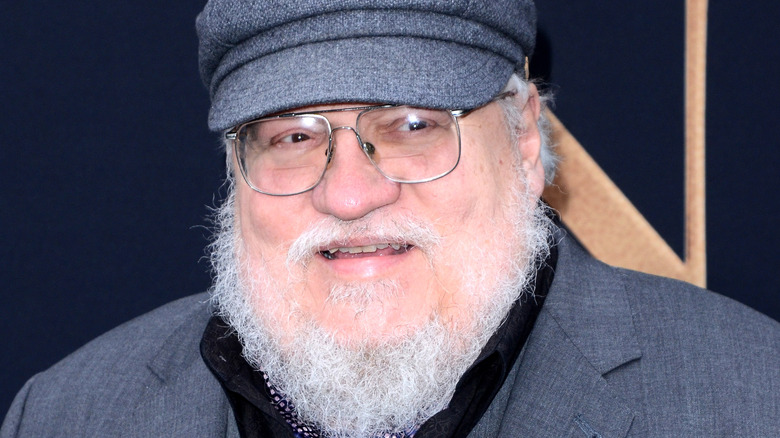

But Benioff and Weiss wanted to move on with their lives, and negotiated to wrap up the show with two shortened seasons instead. Author George R. R. Martin, much like the shows fans, didn't understand why. "We could have gone to 11, 12, 13 seasons," he told Variety, "but I guess they wanted a life."

The shorter seasons meant that no matter what, the portentous, chaotic endgame of a complex story would have a lot less runway to make its landing than the show had when it took off. "House of the Dragon," if it becomes successful enough, would do better to maintain a consistent season length.

Have lots of dragons, obviously

This might seem like it goes without saying for a show called "House of the Dragon," but dragons had better be prominently featured. By the time "Game of Thrones" arrived at its finale, the show was down to one dragon out of its original three. For a while, we rarely saw Drogon, Viserion, and Rhaegal on screen all at the same time, as the show gradually had to increase its budget for more and more CGI. The final seasons had some occasionally satisfying dragon battles, but they largely existed on the show as an allegory for "the nuclear deterrent," according to George R. R. Martin (via Vulture).

Dragons have so much more potential than as flying weapons of mass destruction. Here's hoping the new HBO spinoff borrows a page from the "How To Train Your Dragon" franchise and gets into the day-to-day life of a dragon-filled household. What do they eat? Do they have distinct personalities? How do they communicate so intuitively with their Targaryen riders? How does it affect warfare when both sides have multiple dragons?

"House of the Dragon" should have far more opportunity for dragon-on-dragon battle action than "Game of Thrones" lone episode with one, as the undead Viserion fought his brothers in "The Long Night."

Commit to fantasy elements

The biggest casualty of the rushed conclusion of "Game of Thrones" were all of the magical and fantasy elements. For all the scheming and speculating about the Iron Throne, fans were left with dozens of unanswered questions about basically every supernatural element of the show. Why did we spend eight seasons dreadfully anticipating the arrival of an army of the undead, only for then to all fall over when the Night King took his eyes off the ball? What was the metaphysical significance of Bran's transformation into the "Three-Eyed Raven," other than to reveal a key plot detail from the past? What was the deal with the Children of the Forest? Did anyone turn out to be the "Prince that was Promised," or was that just a red herring?

It's not that "House of the Dragon" has to have concrete answers to the metaphysical issues it may bring up — after all, ambiguity is half the fun of fantasy storytelling. But the show would be wise to avoid drastic, abrupt reversals in the priorities of its storytelling. The white walkers in "Game of Thrones" were a wonderful allegory for the larger existential threats humanity ignores while it squabbles over power and politics — climate change, for example. But hey, maybe Arya can get the drop on climate change while it's distracted, too.

Avoid obvious "plot armor"

A huge reason that "Game of Thrones" became so popular in its first several seasons was the idea that no character is safe from death. Nearly every story suffers from a little bit of "plot armor," a cynical name for the expectation that you can always tell certain characters are too central to the story to die.

Indiana Jones might face certain death a half dozen times in two hours, but these threats are robbed of a certain amount of drama by his name being in the title of the movie. With its shocking beheading of Ned Stark in the next-to-last episode of Season 1, "Game of Thrones" announced loudly to the world that it stood in defiance of the convention. It bolstered that reputation in a huge way with several of our ostensible "heroes" biting it suddenly in Season 3's Red Wedding, and continued to shock with surprising deaths and twists each season.

At the end of Season 5, however, showrunners got cocky and decided they had earned such a reputation for chaos they could pretend to kill off Jon Snow. The (still) most recent volume of the books, "A Dance with Dragons," ends with a cliffhanger as Jon Snow is stabbed by his own men in a mutiny. The showrunners took that cliffhanger and ran with it, showing Jon Snow definitively a corpse. Fans of both books and the show didn't buy it, however: As one of the few remaining point-of-view characters and potential heir to the throne, everyone was pretty sure he wouldn't be dead for long.

"Plot armor" cuts both ways — sometimes you waste too much time threatening a character everyone knows won't die, other times minor characters survive when they have no right to. Near the end of the show, viewers were primed for the Battle of Winterfell in the episode "The Long Night" to have major casualties, but instead only Jorah Mormont fell as dozens of other more dramatic deaths were magically avoided despite the scale of the undead. No one is saying it's easy, but it is a lesson for "House of the Dragon": if you're going to call attention to the pervasive threat of death, you have to stay even more steps ahead of your audience than usual.