Cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel Opens Up On Cherry And Da 5 Bloods - Exclusive Interview

The Apple TV+ film Cherry sees the Russo Brothers taking a break from the superheroic exploits of the Marvel Cinematic Universe to tell a more intimate story about one man's descent into opioid addiction. As such, you might expect it to be less visually imaginative than their work on films like Avengers: Endgame. While there is certainly a shortage of CGI-rendered space tyrants in Cherry, however, it does come with an arresting visual style that makes bolder use of cinematography than one might expect out of a character study.

Much of that aesthetic can be credited to cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel, working directly with the Russos for the first time after shooting the action-packed Extraction, which the brothers produced. Sigel has been plying his trade in Hollywood for over two decades, shooting for acclaimed directors like George Clooney, Stephen Soderbergh, and Spike Lee. His work on Cherry imbues the film with a distinctive visual identity that shifts over time in step with the emotional and psychological journey undertaken by the title character, played by Tom Holland.

We sat down for a chat with Sigel to discuss how he shot some of Cherry's standout scenes, working with Spike Lee on Da 5 Bloods, and what we can expect from his next project, the Channing Tatum-directed Dog.

Newton Thomas Sigel talks working with the Russo Brothers on Cherry

What's it like working with the Russos? How did they approach creating a visual style for Cherry?

Well, I think Joe and Anthony really haven't gotten a lot of credit for some of the very strong visual ideas that they have. Marvel has certain demands. The audience has certain expectations in those movies that lead you in one direction, I think, or in a certain direction that has a certain prescription. And I think by going on to Cherry, they really were looking to get back to a lot of the roots where they began in filmmaking, which was more of an indie kind of a flavor. Even as they got into television, and things like Community, their episodic work always had that sort of edgy, indie spirit. I think for them, Cherry was a time to really play.

And I think the fact that it was shot in Cleveland, that it was a story very close to their own experience growing up, they just felt really free to let their imagination run wild. For me as a cinematographer, that was fantastic, because while they knew that they wanted a certain kind of bold solution to some of the more outrageous elements of the story, they were very open to and actually encouraging of me to give them ideas of execution for the thematic ideas that they were playing with.

That was very rewarding, and it's one of those things where I learned early on that one of the great things about the clarity of their vision was that, when you did throw out an idea, you'd get a response and you'd know very early on whether it was a direction you were going to go or not. One of the things I've learned as a cinematographer is that if something is not clicking with a director, if there's something that is rubbing them the wrong way or that doesn't sit right, you don't push it, you move on and you don't have any emotional attachment to that idea. With the Russos, when you did give an idea, you could tell when they were going to embrace it.

So I always wanted to be clear and confident in the ideas that I put out to them, because I knew that if it clicked, it was going to be in the movie. And so, as you put out your riskier, more outrageous ideas, and you see the response, that kind of gives you a guide as to if we're moving in the right direction or not. I think every movie has to find its voice and no matter how much you think it's all there in the screenplay, the minute you start putting images and sounds to those ideas, the film very often takes on a whole new life, a whole new voice.

Can you offer an example of one of those riskier ideas that gestated between you and the Russos?

Well, we talked about basic training. For them, they always thought that basic training was a chapter; it was a section that they called "absurdism," that there was a kind of absurdity to it. For me, it was how to bring that about, but also understand the severity of the decision that he made joining the army, understand the fact that even though he finds out that Emily, his love, is not leaving him or is not leaving Cleveland, and he didn't have to join the army. It's too late, he's made the choice and he's boxed in.

So we move in the aspect ratio, and we moved it into a 166, a more square aspect ratio than in the rest of the movie. We also know that this decision, instead of letting him be this slightly more passive traveler of life that he is when we meet him in the opening of the movie, being in the army is going to put that situation right in his face.

And you can't walk away from it. You can't blink, you can't decide you're not going to do it on Thursday. So we chose to do it all with one lens, all the same focal length, a very wide lens. By using that lens, it almost demands that you're very, very close to the actors. So that whole section was done with one lens, most of it right in the face of the actors, and I think that was an idea that when I proposed it to them, I needed to be sure it would work because they took it and ran with it.

Newon Thomas Sigel on Cherry's ecstasy scene and finding the humor in darkness

Other than the chapter structure, which you've talked about before in terms of the book, what did you take from the novel to influence the look of the film?

I'm not so sure I took anything from the novel, other than the sense of irony. The book is very bleak, much bleaker than the movie really, in many ways. The one way that, for me, I got through the book and that I could not be totally devastated by it was this sense of irony, this sense of being able to look at the absurdity of life. Humans are... we're tough, we're cruel to each other. We're cruel to ourselves, we're self-destructive, we destroy our planet. So it's a very hard world to exist in if you don't have some humor and some kind of ability to look at the most tragic elements of life with a touch of irony and a touch of humor, and it gets you through. It's what got me through the book, and I think it's what we try to imbue the film with, was this notion of irony.

One of the sequences that was particularly striking was the ecstasy scene. We've seen drug use and the effects of it portrayed onscreen for decades. How did you approach coming up with that look and feel for that particular sequence?

Well, what I thought was interesting was that, at the beginning of the film, he's a young college student, he's kind of naive, he's got issues. He has a lot of anxiety. He takes Xanax and he runs into these kids who give him ecstasy. When he goes to the party, this is after his initial meeting with Emily in class and outside the classroom at school, this is like, what a blessing he's crossed her path again, and he's completely infatuated with her. So what we wanted to do was find a way to have him, in this sort of drugged-out state, see Emily, begin to talk to her, and then as he does, for her to sort of ground him, like bringing him back down, almost like a balloon that's floating away and she's grabbed the string and she's pulling it down.

So the infrared was done with an infrared camera and a color camera, and they're shooting the same image in a 3D rig. What that did for us was, it allowed us to go from this completely infrared state where he's really sort of tripped out, and then as he meets her and in the course of the conversation, the color begins to come back in and it begins to bring the balloon back down to earth, and her warmth and her radiance brings his color back into him. By the end of the scene, it's relatively normal.

Our editor Jeff Groth did a great job, too, of working with these little pieces I shot to kind of step outside the narrative, conversational dialogue that was happening and put you into the internal, subjective thought bubble of Cherry. You see it in these infrared shots of him touching her jacket, and you see it even on Emily, when as the dialogue progresses, there's a closeup of her that is completely non-verbal, but the dialogue is still going on. That's a technique that I find very effective, and I really liked the way that Jeff and the Russos put that together.

How much do the actors you're shooting affect how you approach styling the film visually? Once you know, okay, Tom Holland is my star, a lot of this is going to be centered around him, how does that affect what you do?

You know, I'm really driven by the story more. If a particular actor brings something that is so uniquely theirs, that it's like, oh my God, now that we have Tom Hardy in the role, it's going to be a different kind of movie, then maybe you start to rethink it. But my ideas for the execution of the visual storytelling really are coming straight out of the script and the conversations with the director. Maybe sometimes you can see with a particular actor certain ideas, how well they're working and maybe for this particular actor, you goose a little more this way or that way. But I don't find that an individual performer changes the way I would do a scene or a movie.

Bringing Da 5 Bloods to life with Spike Lee

What was it like working with Spike Lee on Da 5 Bloods? He's a director who has an iconoclastic style visually. What was it like going into that project?

Well, it was really interesting. It's been quite a few years for me, as I've kind of rolled from one movie to another. So to go from Bohemian Rhapsody, which is this wonderful, bittersweet story of Queen, to India and Thailand for Extraction, where you're just full-out adrenaline rush, to Spike's Da 5 Bloods, where you're back at war, but you're really there to understand what that meant and what that meant to America, what it meant to the Black experience. Spike, I've known a long time, I've done commercials with him, he developed a style very much his own that changes from film to film, but a lot of the DNA of it has been there for a long, long time, going all the way back to Do the Right Thing, or maybe She's Gotta Have It.

So, it was great. Spike is very extremely decisive. He works very quickly, but the good thing about that is it inspires a lot of confidence in the cast and crew, because he so clearly seems like he knows what he wants. I think probably one of the biggest learning curves for me in the movie was that he really saw it as an ensemble piece. It was Da 5 Bloods. So it just more and more got geared toward group shots, three shots, five shots, and he wasn't looking for that closeup.

So that made it very interesting. It was a very interesting bit of storytelling, I thought. But also, the subject matter is so powerful and it was such a novel way to show it — not novel if you like The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, I suppose, but to take The Treasure of the Sierra Madre... my first time around it was taking it to Iraq with Three Kings, and now I'm taking The Treasure of the Sierra Madre to Vietnam with Spike Lee, so clearly those themes have served us well.

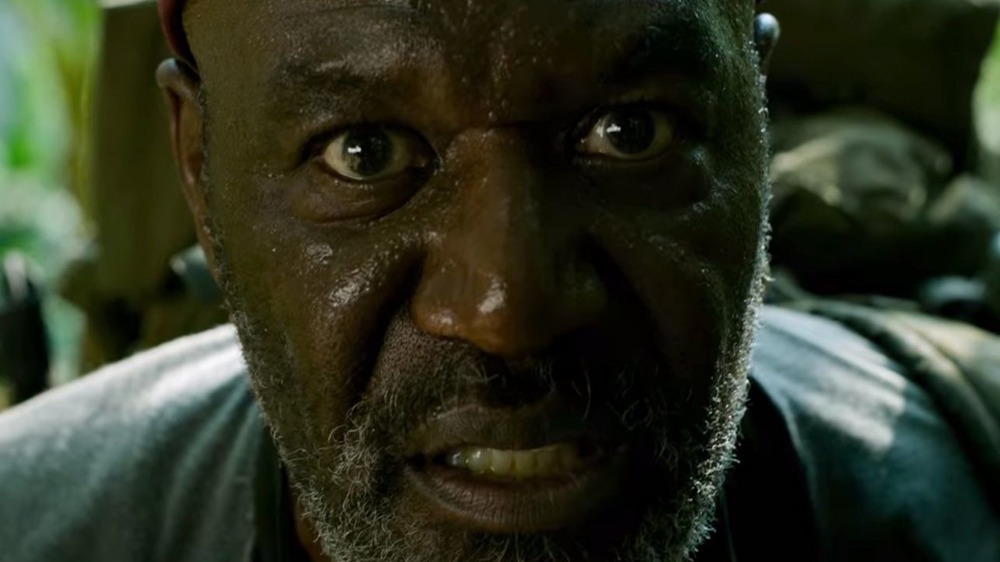

It's interesting you say that about the ensemble, because one of the most striking shots from that movie is Delroy Lindo's monologue, where it's just him and just his face.

Well, Delroy's an amazing performer, and you could see as the movie progressed that, as much as it was ensemble, and it was designed as an ensemble piece and even titled such, it really was Delroy's story in many ways. He really started becoming the heart and soul of the movie. I think it's part of what makes that soliloquy so potent, is that you've spent so much time in this group and you've spent so much time with them as a group that all of a sudden, while they're off still as a group, you have this one lone wolf that is looking right in the camera and pouring out his heart and soul to the point where finally, when he looks up to God and comes down to see the ghost of Norman. That soliloquy was extraordinary. You could tell on the day that you were filming something really unique and spectacular.

Newton Thomas Sigel on Channing Tatum's directorial debut, Dog

Is there anything you can tell us about Dog, the upcoming project you're working on with Channing Tatum? It's his directorial debut.

It's about a dog. [Laughs] No, Dog was great, man. Like everybody else, I got shut down in the middle of a show when COVID hit, and Dog's my first time back to battle, and Channing and his partner Reid Carolin directed it. You never know, when an actor's going to direct a film, what does that mean, especially when he's starring in it. But I've got to tell you, it was such a wonderful experience because first of all, Channing and Reid are really tight. They go way, way back. The story was a very personal story for him because Channing had a dog named Lou that was everything to him, and it died right around the time when he was having some family issues as well. The death of the dog, I think, really impacted him very profoundly.

That led to a documentary that he and Reid made called War Dogs, which was about these dogs that are trained to help the servicemen overseas, and it sparked a whole story in them and they wrote it and we shot it. It was just so much fun. It was just one of those experiences where you really enjoy going to work, and you like the guys, and you have fun with them. Some of these are... they just kick you in the gut every day. Some of them, you just wake up in the morning and you're really glad to be heading off to work.

So Dog was a really good experience in that way. I think it's going to be a really good movie, and it deals with a very serious subject, but I've got to say, and in a very different way than Tom, but Channing Tatum is one of those actors that is really instantly likable on screen. He's just one of those guys that you want to root for. And he's funny. He's very funny, just naturally.

So I think when you see the movie it's going to, in a very different way than Cherry, have a certain absurdist humor to it, and it's going to make dealing with a tough subject more palatable. I'm looking forward to it, and for me, it was a much lighter movie than some of the other ones I've been doing lately. I think at this time the world could use a few uplifting moments.

Is there a different approach when you're working with someone who doesn't have a lot of directorial experience, versus some of these guys who've been around and are more familiar with the filmmaking process?

I found that every director is so radically different in terms of how much they're about the camera, how much they're about the actors, how much they're about the writing and the words. And I try to fill in the gaps. I just try to figure out where I can fit in and make it whole, and with Channing and Reid, I think they looked at me a lot for how we were going to shoot it, like the style of the shooting and cameras, lenses. But that's not to say that they just said, "Where are you going to put the camera, Tom?"

I think they both have a very keen eye. Channing has an amazing fine art photography collection. There's a keen acuteness of composition and imagery. It was great because they had confidence in me to help them figure out how you're going to tell the story with the camera, and yet they were great collaborators in finding those great frames and those great visual ideas. So yeah, the last few years have been such a blessing. Man, it's been great.

You've worked across a lot of different genres, from war films to superhero films. What genre of film do you find the most challenging, or what are the unique challenges that you see out of each of those things?

Well, they all have their own challenges, obviously. I don't really do much comedy, like traditional comedy. I think comedy is very hard in the sense that it's got to be funny. When they do these test screenings of films, they're so subjective, but the one time when I find that they're not subjective and that when an audience response is absolutely the most valid thing is in a comedy. You go and you sit in a theater with 500 people and something's supposed to be funny, and nobody's laughing. No matter how funny you think it is, guess what? It's not funny. So, that's a genre that I think is challenging in a very different way, and it's just not one that I've ever really... I've only done a very few, and they're definitely not sort of the top of my resume, as we say.

I think things like science fiction have a huge challenge, because they're world-building, and when you build that world, you have to make it believable or you have to sell it. I think doing something like a Freddie Mercury story is very challenging because you want to get it right, but you also want to make it dramatic and you want to figure out when it's okay to take some poetic license and when it isn't.

I think every genre has its challenges, just like every aspect of cinematography does. On Monday, I start a new show, and it's day exterior, and my biggest challenge will be that the sun, if it even decides to come out, I have been told it will not stay in one place. So I have to deal with that all day long because in my movie it has to stay in one place. What are you going to do?