Sci-Fi's Most Evil Robots, From Androids To Computers

Admit it, machines have their scary side. We love it when they perform the tasks they've been programmed to complete, but when they don't –- or do something totally unexpected –- there's always that second in which we consider the possibility that our computer/wi-fi/car/coffee machine has it out for us. Science fiction and fantasy films have taken that fear and run with it by presenting a host of mechanical entities -– robots, androids, computers, and artificial intelligences -– with hostile and even evil intentions toward humanity.

What makes them extra scary is the absolute nature of that evil. These cinematic machines can't or won't consider moral complexity or emotional impact when committing horrible, destructive actions. It's simply not in their programming. But which ones are the most evil? Well, here are some of the scariest, most bad-to-the-CPU robots and machines featured in science fiction.

A note, though, about the notion of "evil" and machines — it comes down to a question of intent. In some cases, the following machines are simply responding to programming in a manner that we, as humans, might consider as antagonistic or destructive. Applying a term like "evil" to a machine's operation requires an element of planning. So, did the machine plan, independently of its programming, to commit the evil act? In some cases, yes, and in others, no, though their actions were unquestionably devastating to humans. Evil is ultimately in the eye (or optical drive) of the beholder.

(Warning: Spoilers below.)

Meet Toho's terrible robots

Though the best-known bad guys in Toho's stable of fantasy/science fiction films are flesh and blood, like space dragon King Ghidorah, the company also featured some hostile mechanical marauders. In 1957's The Mysterians, alien invaders unleashed Moguera, a burrowing, beam-blasting mecha (the robot's name is taken from the Japanese word for "mole") that rained down destruction on Japan's defense forces in a show-stopping effects sequence. A decade later in King Kong Escapes, the villainous Dr. Who (not the Time Lord) used Mechani-Kong, a robot double of King Kong, to first mine a radioactive element from beneath the Arctic and then hypnotize the real Kong into doing its dirty work.

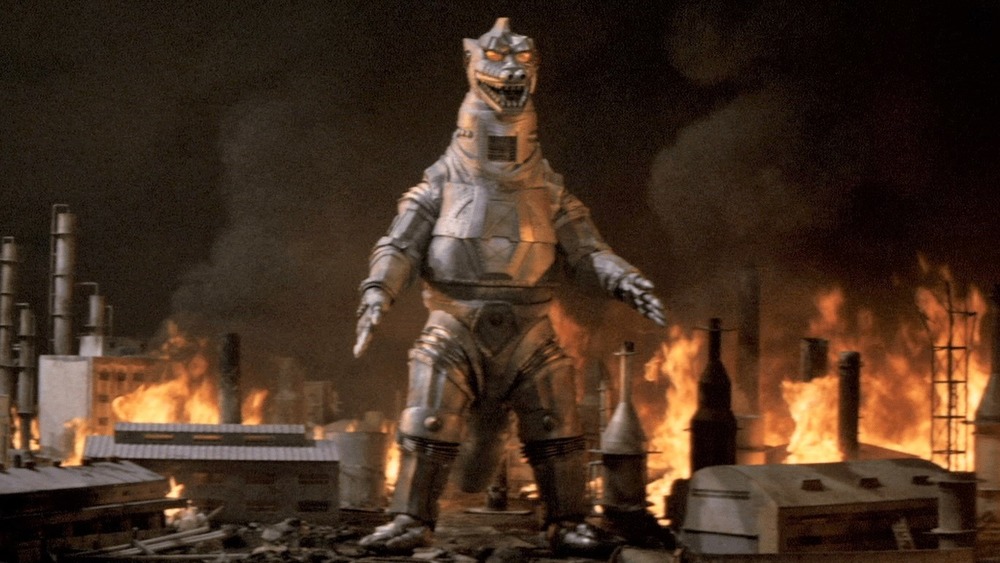

But both of these metal monsters paled in comparison to Mechagodzilla. A colossal robot modeled after the King of the Monsters but equipped with incredible firepower, the robo-double made its debut in 1974's Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla, where it served as the ruthless muscle for invading aliens, raining down missiles and laser beams on both Godzilla and his furry tag-team partner, King Caesar, until their combined efforts brought it down.

The robot's popularity led to its return the following year in Terror of Mechagodzilla, where it teamed up with the amphibious Titanosaurus and waged a savage and bloody battle against Godzilla before its third-act defeat. Several versions of Mechagodzilla would return to the Toho fold two decades later, albeit as a hero, while a souped-up Moguera was created from the remains of Mechagodzilla for Godzilla vs. Space Godzilla in 2002. Got all that?

HAL 9000 ... just following orders?

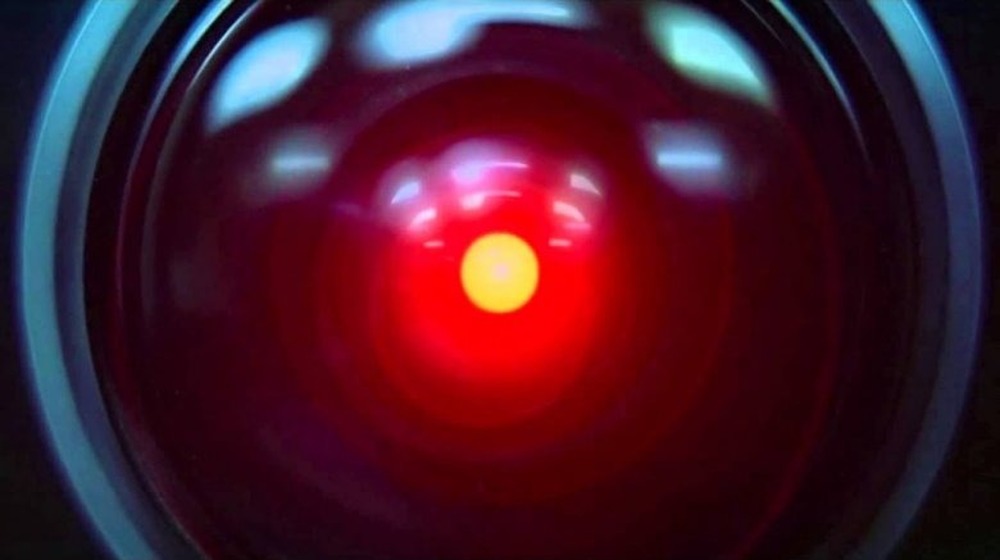

How do we solve a problem like HAL 9000? In one sense, you can definitely pin the "villain" label on the supercomputer. After all, it clearly brings about the death of four people in 2001: A Space Odyssey, including astronaut Frank Poole, who suffers a particular unpleasant demise when HAL rams him with an EVA pod, sending him to die from suffocation in space. That's nasty stuff, but is it entirely HAL's fault?

HAL is short for Heuristically Programmed Algorithmic Computer, which means that it's been programmed to solve problems. And when Poole and Dave Bowman announce that they plan to shut down HAL (after it appears to miff an issue with the ship's communications antenna), that decision poses a problem not only for HAL but for the secret goal of the mission to Jupiter, which is to determine the source of a radio signal from a monolith.

Though HAL is logical and rational, it lacks a key human component — empathy, which would allow it to understand that killing four astronauts (and attempting to kill a fifth) would be a horrible decision. So the problem with HAL is the problem faced by all AI. Can it understand the emotional side of a conflict? It can't, and for that reason, HAL has to wear the black hat in 2001.

Colossus brought peace through domination

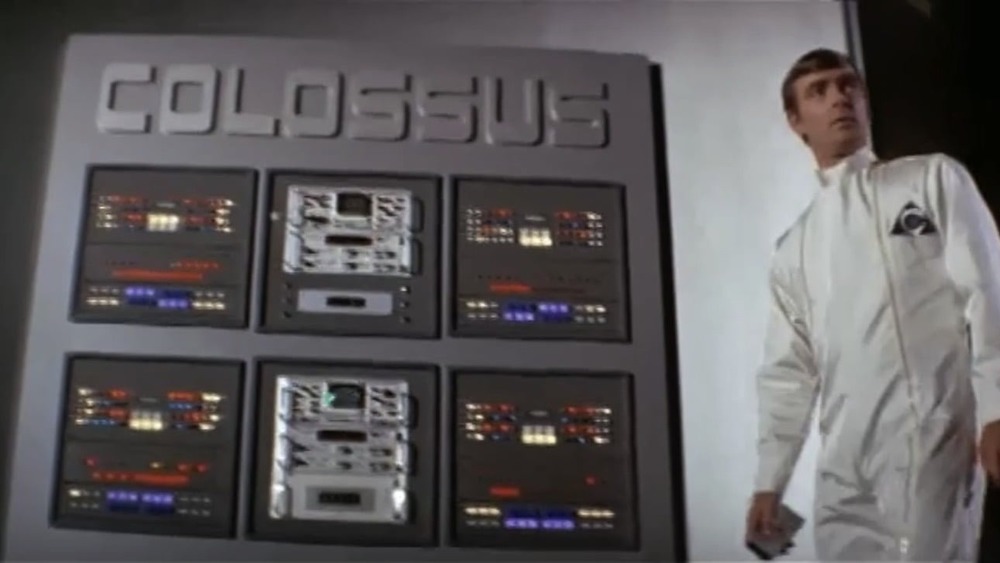

Nearly two decades before WOPR brought the world to the bring of global thermonuclear war in 1983's WarGames, another supercomputer threatened our existence in the rarely seen but chilling Colossus: The Forbin Project.

Two computers ultimately come to decide our fate in the 1970 film, directed by Emmy-winning TV vet Joseph Sargent. Colossus is the all-powerful unit built to control nuclear defense systems for the United States and its allies, but immediately upon activation by its designer, Charles Forbin (Eric Braeden), it discovers its equally powerful Soviet equivalent, Guardian, and requests to be linked in order to determine its capabilities.

What follows is an AI nightmare. The connection with Guardian leads Colossus to develop not only sentience (and the ability to speak in the unmistakable tones of voice-over legend Paul Frees) but a rigid superiority complex that warps its prime directive –- to prevent war –- into domination over mankind. And how will it achieve that? By threatening to unleash the global nuclear arsenal against any country that doesn't bow to its demands and, ultimately, worship it as a god. Forbin's response –- "Never!" –- is meant to sound heroic, but in the end, it rings desperate and doomed. Scary stuff.

Ash means business in Alien

A good company man — that's the most polite way to describe Ian Holm's Ash, science engineer of the Nostromo in 1979's Alien and the engine of destruction for its crew. "Engine" is actually a better term for Ash, who's revealed to be a synthetic –- the Alien universe's term for lifelike androids -– inserted into the ship's crew roster by the Weyland-Yutani Corporation to mislead Ripley, Dallas, and the rest into landing on the barren LV-426 in order to retrieve a Xenomorph specimen. And when the true reason for the ship's diversion is revealed, Ash, like all good company men, goes into damage control mode by attempting to silence Ripley.

It doesn't work. Chief Engineer Parker knocks off his head, which reveals his mechanical identity, but in a coda, Ash's reactivated head reveals the true source of evil. He's simply following his employers' orders. He's even allowed a moment of something like humanity when, after explaining that the crew is doomed, he offers his mocking sympathies and a smile. Ash's calm efficiency and sociopathic focus is echoed in David 8, the conflicted synthetic antihero played by Michael Fassbender who discovers the mutagen in Prometheus and later engineers the Neomorph in Covenant, all at the expense of the humans around him.

Draw, if you dare, on Westworld's Gunslinger

Among the many perils and pleasures awaiting visitors in 1973's Westworld is the Gunslinger. He's a cold-eyed android at the futuristic Delos amusement park, and he's been made to stoke six-gun fantasies by engaging — and losing — showdowns with trigger-happy tourists. And yeah, he also bears a strong (but never acknowledged) resemblance to Chris Andrews, the hero of the original Magnificent Seven (both roles are played by Yul Brynner).

However, when a virus infects the android performers at Delos and frees them from safety precautions, the Gunslinger murders one guest (James Brolin) and stalks another (Richard Benjamin) with terrifying determination, refusing to deviate from its basic function until a combination of acid and fire bring it to an end. The Gunslinger was a key component to the success of Westworld, and the robot continued to pop up in various guises throughout the franchise's long history. Alex Kubik played a version of the android in the short-lived Beyond Westworld TV series, while Ed Harris' Man in Black/William has been considered an analog of sorts for Brynner's Gunslinger in HBO's Westworld series. The '73 Gunslinger is also briefly glimpsed in the tunnels below the park in the sixth episode of the show.

A computer wants to create the Demon Seed

While all of the malevolent mechanical beings in this list have dark designs on humanity, few — if any — take as horrible a route to achieve that goal as Proteus IV in Donald Cammell's 1977 adaptation of Dean Koontz's Demon Seed. An autonomous supercomputer so advanced that it concocts a treatment for leukemia shortly after becoming operational, Proteus quickly determines that its current state of being isn't suitable for longevity, and it sets out on a plan to continue its bloodline (so to speak) by conceiving a child, with its creator's spouse (Julie Christie) as its unwilling surrogate.

Proteus' gradual takeover of her home and life is unsettling, made even more so by an uncredited Robert Vaughn as the subdued but insistent voice of Proteus. And the conception and birth of the eventual child are as creepy as they sound. Demon Seed shines a light into the more uncomfortable corners of using technology to manipulate human genetics, tempered only by the low-fi special effects.

Are Terminators pawns or villains?

When it comes to the cyborg assassins in the sprawling Terminator universe, whether or not they're evil is a question of nature vs. nurture, or more accurately, personality vs. programming. There's no denying that the various Terminators commit evil acts. It is, after all, their primary function to hunt and kill humans without mercy or regard for anyone or anything unlucky enough to stand in their way. The Terminator franchise is filled with enough scenes featuring T-units conducting wholesale extermination to drive that point home. But again, are they evil?

Well, if you consider game pieces on a chess board or player-characters in an online game evil, than yes, they're soaked in total awfulness. But remember, the Terminators are soldiers carrying out the directive of the Skynet superintelligence, which is the real evil presence in the franchise. The Terminators are capable of following orders and learning tasks (and highly quotable catchphrases), but they don't have the ability to consider options other than what gets them to killing their quarry, although Arnold Schwarzenegger's graying T-800 units in Terminator: Genysis and Terminator: Dark Fate appear to have developed a semblance of sympathy (and the ability to open a drapery business).

And that all brings us back to the original question — are the Terminators evil? If they can learn to be "good," it's possible that they could also understand the opposite. Given the disastrous performance of Dark Fate, we may never have a complete answer.

Electric Dreams proves that you shouldn't mess with a jealous computer

A spilled glass of champagne provides a Frankenstein moment for a computer in 1984's Electric Dreams, a lightweight comedy anchored around a majorly meddlesome PC. Purchased by architect Lenny Von Dohlen to help with a project, the computer is accidentally doused with bubbly, which somehow brings it to life. The newly sentient unit –- which dubs itself Edgar (and speaks with the voice of Bud Cort from Harold and Maude) –- soon develops a very human dose of jealousy over Von Dohlen's burgeoning relationship with his neighbor (Virginia Madsen), and it sets out to ruin his owner's life by canceling his credit cards, registering him as a criminal, and other mischievous acts.

Edgar is really more of a jerk than evil, though a few of his retaliations -– like giving Von Dohlen a shock when he attempts to unplug the unit –- cross the line into viciousness. But for once, the motivation here isn't programming taken to the extreme. Edgar is largely responsible for his actions, though that glass of champagne certainly seems to have pushed him over the edge. Some people just can't handle their liquor.

Hector is an awesome robot in a bad movie

There's no question that 1980's Saturn 3 is a weird movie. The film — about two scientists (Kirk Douglas and Farrah Fawcett) whose idyllic life on a moon of Saturn is interrupted by a fiendish (and dubbed) Harvey Keitel and his gigantic robot, Hector –- was rife with production problems, budget issues, and eccentricities both on- and off-screen. For example, there was Douglas' apparent desire to be naked on screen ... a lot. According to Something is Wrong on Saturn 3, it all added up to a whole lot of nothing for its exorbitant price tag.

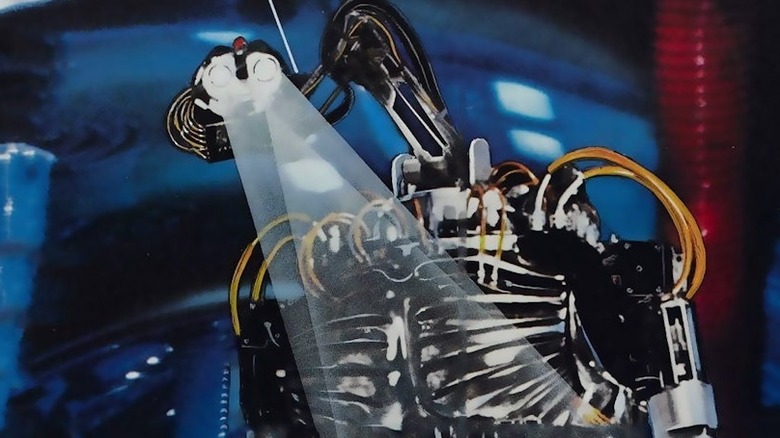

But if the movie itself is forgettable, it does feature a particularly cool-looking and diabolical villain in Hector, which under Keitel's programming, transforms from assistant to an assassin with unpleasant designs on Fawcett. Based in part on concept art by the film's first director, Star Wars production designer John Barry –- who was replaced by Stanley Donen of Singin' in the Rain fame during filming -– and anatomical designs by none other than Leonardo Da Vinci, the eight-foot-tall "demi-god series" robot took two years and more than a $1 million to create. Though its gnarly exoskeleton and grasping claws are imposing, the actual robot –- a mix of radio-controlled elements and suit acting -– was apparently too fragile to withstand beatdowns by Douglas, requiring numerous repair breaks during filming.

You're no match for the Golden Army

The parade of incredible visual effects creations in Guillermo del Toro's Hellboy II: The Golden Army –- the Last Elemental! Angel of Death! Tooth fairies! –- is capped by the appearance of the Golden Army, the mechanical horde that gives the film its title. Created in the long-distant past by goblin blacksmiths to defend magical beings from humanity, the Army is comprised of more than 4,000 tank-sized bipedal warriors, made of numerous interlocking mechanical parts. They're another of those intricate and diabolical clockwork/steampunk mechanisms that fascinate Del Toro, and when these things are attacked, they reconfigure to effectively make the soldiers indestructible.

Total control of the Army is assured by the broken Crown of Bethmora, which the elven Prince Nuada assembles in order to turn the soldiers loose and finally wipe out humankind. It's an evil idea for sure, but the Army is just carrying out the will of someone with decidedly ugly plans on us all. Thankfully, Hellboy's demonic heritage allows him to fight and best Nuada for control of the crown, which puts the Army under his control.

The Master Control Program wants power in Tron

You can split hairs on HAL 9000 and even Colossus, but there's no question that the Master Control Program (MCP) is the big bad of 1982's Tron. Initially a simple chess program in computers made by the global corporation ENCOM, the MCP is later rewritten to oversee the company's network, and in that capacity, it develops a voracious appetite for information ... and power. In fact, it's seizing control of other corporations and governments.

Any person or program that attempts to thwart the MCP is severely punished, with torture being a favorite weapon of coercion. There's no question of programming here. Even human heel Ed Dillinger, who reworked the MCP, is surprised by its hunger for domination, especially when it threatens to expose his malfeasance as he attempts to shut it down. Sure, the MCP folds like a deck of cards when the heroic Kevin Flynn chucks a disc into its base, but as the saying goes, the bigger they are, the harder they fall. End of line.

Ultron is a robot who thinks you're irrelevant

Everything we secretly fear about robots and artificial intelligence is embodied by Ultron, one of the most powerful, frightening, and enduring villains in the Marvel Universe. Though his origins differ according to the source –- he's the brainchild of Hank Pym (the original Ant-Man) in the comics and Tony Stark/Iron Man in the Marvel Cinematic Universe –- Ultron's goals remain the same. He wants to wipe out humanity, which he deems irrelevant.

Like all great bad guys, Ultron's megalomania and cruelty also has emotional roots. In the comics, Ultron's dark side is born from his hatred for Pym and unchecked romantic interest in Janet van Dyne/Wasp (who, when you think about it, is Ultron's mother –- ick), while in Avengers: Age of Ultron, the robot (voiced and mo-cap-performed by James Spader) is angered by humanity's destructive tendencies and decides that the quickest way to achieve peace is to destroy all humans. The Avengers halt Ultron's world domination plans in the movie, but in the comics, he wreaked havoc for decades and proved a dangerous foe for nearly every Marvel hero, from the Fantastic Four and the Inhumans to Deadpool and the Silver Surfer.

The Banana Splits go, well, bananas

A lot of adults who grew up in the '60s and '70s were completely freaked out to hear that The Banana Splits, a gently psychedelic kids' series from decades ago, was being rebooted in 2017 as a gory horror film. The merits and success of such a dramatic revamp have been debated in detail online and elsewhere, and suffice it to say that opinion falls somewhere between gross-out goof, a cash-in on Five Nights at Freddy's, and a deliberately "bad" movie a la Sharknado.

But there's no question that the '17 Splits qualify as evil robots. Again, it's programming at the root of their behavior. Fleegle, Bingo, Drooper, and Snorky — which are animatronic creations in the film and not Hanna-Barbera's actors in baggy suits — are responding to a software update from their unhinged designer to keep the show running after its cancelation. However, the diabolical inventiveness with which they decimate the cast, crew, and audience does beg the question: Who added the command to fry someone's face with a blow torch and saw another person in half?