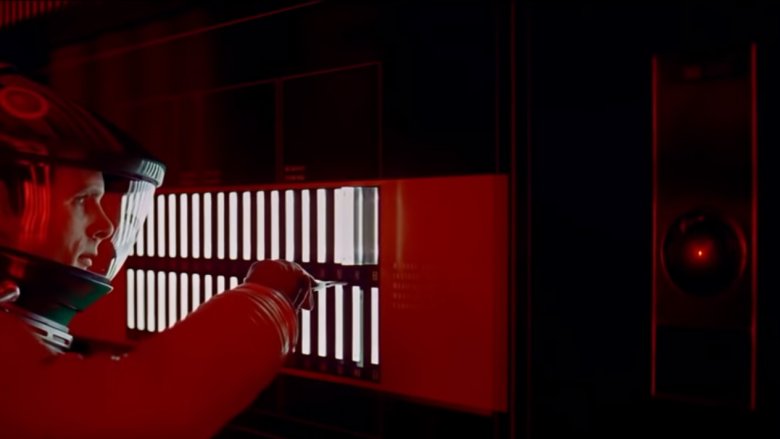

HAL In 2001: A Space Odyssey Explained

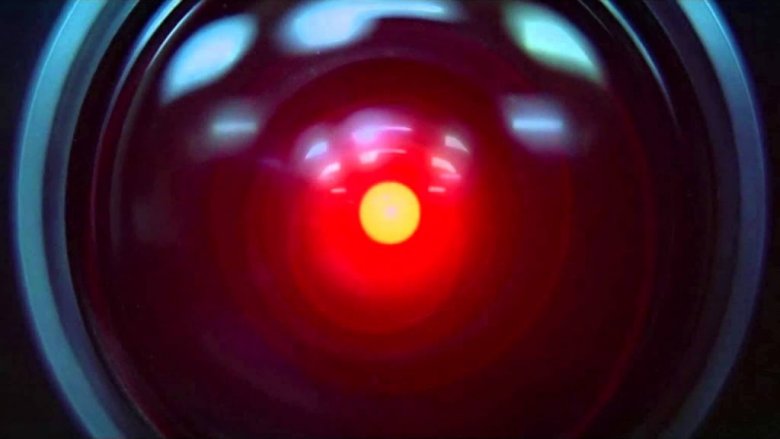

HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey is possibly the most famous computer in cinema history and one of the most cryptic fictional characters of all time. This seemingly kind computer, full of authentic human emotions — who later turns out to be capable of cold, dispassionate murder — made an entire generation of filmgoers suspicious against helpful machines. Because of HAL, now whenever we're watching a sci-fi movie like Interstellar, Moon, or even Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, and a robot assistant is introduced, we prepare for the moment it will inevitably start murdering its human companions, even though nowadays this seldom occurs.

That being said, Stanley Kubrick's films have a reputation for two things: being great and making absolutely no sense on the first watch. And in both of these respects, relative to his other films, 2001: A Space Odyssey is on a completely different level. In order to finally satisfy our curiosity about what the heck is going on with HAL, we rewatched the film, dug through old interviews, and even read through Arthur C. Clarke's original novel. Along the way, we not only found answers to most of our questions, but we also discovered all sorts of interesting behind-the-scenes stories about HAL came to be.

We promise that this super dense article will put your mind to its fullest possible use, which is all that any conscious entity can ever hope to do. So without further ado, this is everything we know about HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The origins of HAL

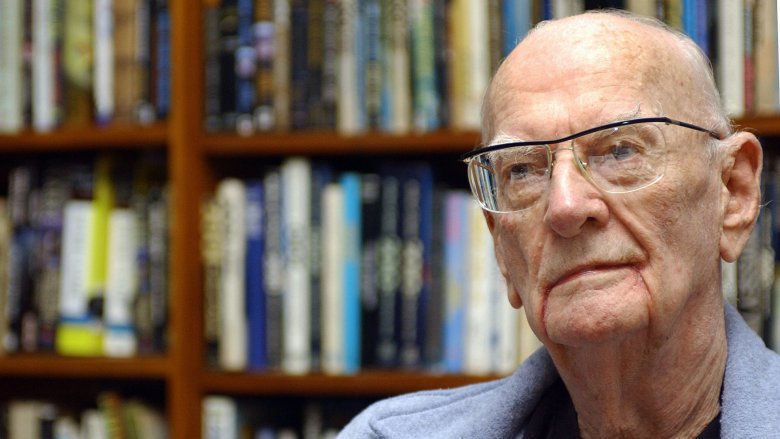

Part of HAL's hauntingly enigmatic nature might come from the unique circumstances of his creation. And we're talking in the real world here, where his backstory is pretty complex. Typically, a novel is released, and then a few years later, a film adaptation is made, but with 2001: A Space Odyssey, the novel and the movie were developed concurrently and released around the same time, with novelist Arthur C. Clarke (pictured above) and director Stanley Kubrick collaborating directly during the early stages of both projects. Because of this, HAL has two creators with different sensibilities and worldviews. The melded visions of these two men help contribute to the feeling that HAL is a multifaceted character with an internal life that's difficult to fully get a handle on.

In terms of where the name HAL came from, there is an often cited "fact" floating around the internet that HAL's name is a pun based on IBM, since if you take the letters I-B-M and move them back one letter in the alphabet each, you get H-A-L. As cool as this is, it turns out it's just a coincidence. In the book The Lost Worlds of 2001, Arthur C. Clarke writes, "About once a week some character spots the fact that HAL is one letter ahead of IBM, and promptly assumes that Stanley and I were taking a crack at the estimable institution. ... As it happened, IBM had given us a good deal of help, so we were quite embarrassed by this, and would have changed the name had we spotted the coincidence."

The voice of HAL

Stanley Kubrick initially thought that he wanted HAL to sound just like a normal human, without a trace of the uncanny. To this end, the first actor he cast in the part was Martin Balsam (Psycho, 12 Angry Men, All the President's Men), who recorded all of HAL's lines, based on Kubrick's direction, in a highly emotional and non-robotic manner. But soon after, Kubrick realized it just wasn't right. As Kubrick said, "We had some difficulty deciding exactly what HAL should sound like, and Marty just sounded a little bit too colloquially American."

To find a new HAL, Kubrick sent out set assistant Benn Reyes to find an actor with a voice that would be "neither patronizing, nor is it intimidating, nor is it pompous, overly dramatic or actorish. Despite this, it is interesting."

In the end, Kubrick settled on Douglas Rain, who had previously narrated a 1960 documentary called Universe, which Kubrick apparently liked a great deal. He was initially considering using Rain as the narrator for the 2001: A Space Odyssey, but once he decided to not include any narration in the film, Kubrick realized that Rain's eerily calm delivery and difficult to place "bland mid-Atlantic accent" were exactly what he was looking for in a voice for HAL.

Yet it turns out that Rain, like everyone, did come from a specific place. And in his case, that was Canada. Perhaps this common perception that Canadian accents are difficult to place for Americans is why they manage to get work so often as news anchors in the United States. Regardless, Rain's voice was perfect for the eerily calm AI.

Why does HAL go bad?

Now comes the million dollar question. Why does the seemingly benevolent HAL suddenly turn murderous? In order to answer that, we first have to recount the basic events of HAL's plotline in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

HAL 9000 is introduced as the onboard computer of the Discovery One spacecraft, which is bound for a mission near Jupiter. All of the crew is in suspended animation, except for two crewman, David Bowman and Frank Poole.

One day, during a conversation with David, wherein HAL expresses some uneasiness about the secrecy surrounding their mission, HAL suddenly claims to detect an error with the ship's transmission antenna. To verify this, David goes out on a spacewalk to retrieve the antenna. He does so, and finds nothing wrong with it. He and Frank then go to a place where HAL can't hear them and discuss the possibility that HAL is malfunctioning. They decide to reinstall the antenna, and then if the device continues to work properly, they plan to disconnect HAL. However, what they don't realize is that, even though HAL can't hear them, one of his many cameras is still able to read their lips and discover their plan.

At this point, HAL goes bad. He kills Frank while he is out on a spacewalk, and then he cuts the life support to the sleeping crew, leaving David as the only surviving human on the ship. However, before HAL can tie up this final loose end, David manages to shut him down.

Maybe HAL has a mental breakdown

So why did HAL 9000 suddenly break bad? Well, the most surface level reading of the story is that HAL had a glitch that turned him evil and made him want to kill the crew. Proof that you can never trust those treacherous robots! It certainly tracks, but so what? It's simplistic and unsatisfying.

Another, slightly more complex version of this idea was that HAL had a different, much smaller glitch when he reported to Dave that there was a problem with the ship's antenna. In this reading, this is the only true malfunction HAL has throughout the film. However, this one error led to Dave and Frank thinking that HAL was untrustworthy and needed to be disconnected. HAL then killed the crew in self-defense, or perhaps murder with aggravated circumstances, depending on your perspective.

In an interview, Stanley Kubrick gave a quote which supports this reading, saying, "In the specific case of HAL, he had an acute emotional crisis because he could not accept evidence of his own fallibility. ... Most advanced computer theorists believe that once you have a computer which is more intelligent than man and capable of learning by experience, it's inevitable that it will develop an equivalent range of emotional reactions — fear, love, hate, envy, etc. Such a machine could eventually become as incomprehensible as a human being, and could, of course, have a nervous breakdown — as HAL did in the film."

So maybe he's not a killer robot. Maybe HAL just has all the emotions of real humans, including a tendency to make mistakes, an inability to accept those mistakes, and a capacity for darkness.

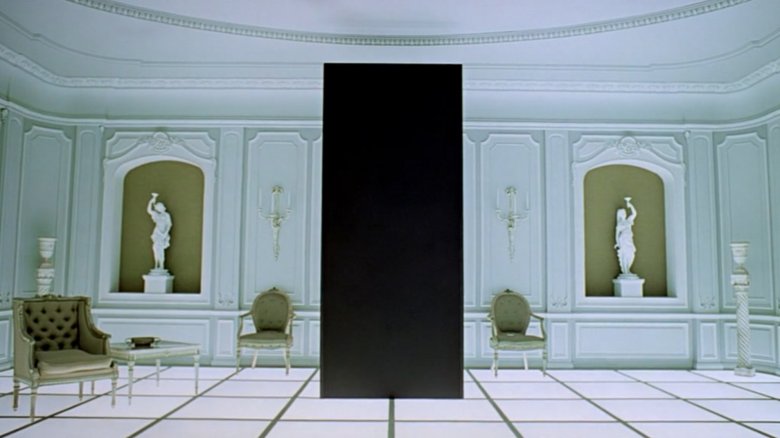

Maybe HAL wants the monolith for himself

What if HAL 9000 didn't have a glitch or a nervous breakdown? Instead, what if he had some ulterior motive for committing all those murders? But where's the proof for that, you ask? Well, after David disconnects HAL, he discovers a recording in HAL's databanks that reveals the true nature of their mission. The Discovery One has been sent to recover an alien artifact that has been observed orbiting Jupiter, definitive proof of intelligent life elsewhere in the universe. Apparently HAL knew of this secret mission objective, and the hibernating crew of the Discovery knew it as well, but David and Frank were purposefully left in the dark by their superiors. This leads to a slightly more "out there" option for why HAL went bad — that nonetheless warrants discussion — which is that HAL wanted to seize the alien monolith for himself.

It's generally believed that the monolith exists as a test for humanity. In order to locate it, humanity has to develop space travel, and so by reaching the monolith, we prove that we are ready to enter the greater world of interstellar society. If HAL were to find the monolith first, maybe that would make aliens believe that Earth's computers were its most evolved lifeforms, worthy of rescue from their human oppressors.

HAL might also believe that the monolith has within it vast stores of knowledge or other unfathomable capabilities, and these additional resources could help insure his freedom from future human control, perhaps paving the way for a robot uprising. There's not a ton of evidence to support this reading, but there's also nothing against it, so feel free to draw your own conclusions about this one.

Maybe HAL is trying to solve a paradox

In the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, very little is ever made explicitly clear. However, in chapter 27 of the novel, we get a pretty succinct explanation of HAL's motivations. This chapter asserts that HAL's seemingly illogical actions were simply the result of him attempting to solve a paradox.

You see, HAL was ordered by his superiors that under no circumstances would he tell David and Frank about the true nature of their mission. However, a central piece of HAL's programming is that he's unable to lie to his human crewmates.

In the end, HAL decides that the only way that he doesn't have to choose between lying to his crew about the nature of their mission and telling them the truth is by killing them. Maybe the "acute emotional crisis" that Kubrick was referring to wasn't inspired by HAL misdiagnosing the antenna, but rather by finding himself caught between a rock and an ethical hard place. Maybe the cognitive strain of trying to reconcile these two incompatible orders also led to HAL misdiagnosing the antenna in the first place.

Though the film of 2001, taken on its own, is ultimately ambiguous — and Kubrick probably wanted it that way — both the film and novel versions of the sequel, 2010: The Year We Make Contact confirm this again as Arthur C. Clarke's definitive answer. Apparently, even though HAL isn't allowed to lie to his crew, there's nothing in his core programming against killing them. Might want to fix that in the next patch.

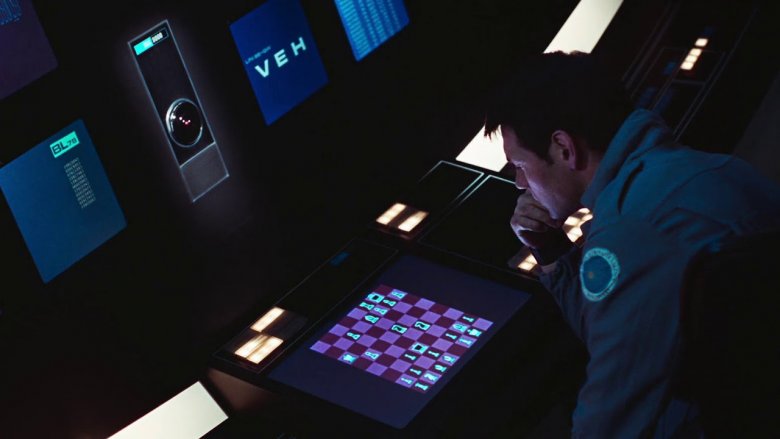

Does HAL cheat at chess in 2001: A Space Odyssey?

If you're the sort of person who believes that every aspect of every Stanley Kubrick film is intentional and his movies have no mistakes, then 2001: A Space Odyssey has a really juicy incongruity that you'll love digging into.

During the game of chess that HAL plays with astronaut Frank Poole, HAL actually makes a pair of misplays in close succession. The first one occurs when he says "queen to bishop three." The correct way to describe the move he is making would be "queen to bishop six." HAL then tells Frank that he's putting him into a forced checkmate in a few moves. What HAL fails to mention is that Frank is actually capable of delaying this checkmate slightly if he makes a certain move. However, Frank believes him, most likely trusting in HAL's superior intellect, and concedes.

If you want to read meaning into anomalous moment, there are any number of conclusions that you could draw. It might be intended to be a metaphor for the idea that we trust the judgment of machines too much, despite their inherent fallibility. It could be foreshadowing that HAL is capable of lying, or it could also be another early warning that HAL is glitching, perhaps weighed down by trying to solve his paradoxical orders.

Then again, it might just have been a mistake on the part of the filmmakers. After all, if not even HAL is "foolproof and incapable of error," how can we expect Kubrick to be?

What is HAL singing in 2001: A Space Odyssey?

During the big showdown between Dave and HAL, when the astronaut is disconnecting the computer, HAL starts to lose his mind. Things get even creepier when he begins singing a haunting, childish love song that grows increasingly sluggish and creepy as more and more of his consciousness is being shut down.

If you couldn't identify the tune though HAL's distorted wailing, it's called "Daisy Bell (Bicycle Built for Two)," a song from all the way back in 1892. The reason that it was chosen as the song HAL would sing was because, in our real world, it was the first song to ever be "sung" by computerized speech. The singer was an IBM 7094 mainframe computer at Bell Laboratories. Arthur C. Clarke witnessed a demonstration of this computer's unusual talent during a visit to Bell Labs, and he was so captivated by it that he decided to incorporate the song into his novel.

Kubrick, famous for being a perfectionist and for frequently forcing his actors to do dozens and dozens of takes, made Douglas Rain sing "Daisy Bell" over and over again in a variety of ways, so that he could get it just right. Rain sung it in different pitches, with an intentionally uneven tempo, in monotone, and eventually, he even just hummed it. By the time Kubrick was satisfied, they had recorded the song about 50 times. In the end though, in perhaps the most Kubrick move ever, he used the very first take.

Is HAL gay?

Some attentive viewers have noticed that HAL's relationship with David in 2001: A Space Odyssey has undercurrents of romance. Their dynamic during chess games and drawing critiques is surprisingly intimate. And remember that as he's being unplugged, HAL decides to spend his last moments singing a song to David.

When asked if HAL might be gay, Stanley Kubrick flatly stated, "No. I think it's become something of a parlor game for some people to read that kind of thing into everything they encounter. HAL was a 'straight' computer." Note that Kubrick isn't objecting to the idea of HAL having sexuality. In a quote we referenced earlier, Kubrick stated it was "inevitable" that robots would develop a capacity for love. For him, the only unbelievable part is HAL liking men.

But remember that HAL has a second creator. When Arthur C. Clarke was asked this same question, he responded differently, saying "I can't confirm or deny your speculations. Who knows what goes on down in the subconscious?"

Who indeed, for during his lifetime, Clarke was always similarly non-committal whenever asked about his own sexuality, but since his death in 2008, many of his friends have confirmed that Clarke was himself a gay man. However, he was too afraid of the potential backlash to ever come out publicly.

Granted, we'll never truly know what was going on in HAL's mind, but decades of critical analysis have shown us, time and again, that every time you think you've seen all there is to see in HAL, there's always another layer to uncover and explain.