The Best Slow Burn Movies

There are a few things in life that require patience and are also special enough to be worth the wait. Dessert, for example. Sunsets. And sometimes, the slow but calculated realization of a meticulously plotted film. A slow burn gives extra meaning to the intense climax toward which it builds, juxtaposing it with the overarching tone for added suspense and impact. There is more opportunity to learn a character's motivations, become delightfully bewildered by red herrings, and begin to itch for closure.

If someone cautions you to avoid a movie because it's slow, don't write it off too quickly. While many films don't really go anywhere and take their time getting there, not all slow films are created equal. To say that the journey is the destination in these slow burn films would be to miss the point: The journey and the destination are each a work of art in and of themselves, and every minute of both is worth the watch — and the wait.

(So if you're still waiting to see them, use caution: Spoilers may follow.)

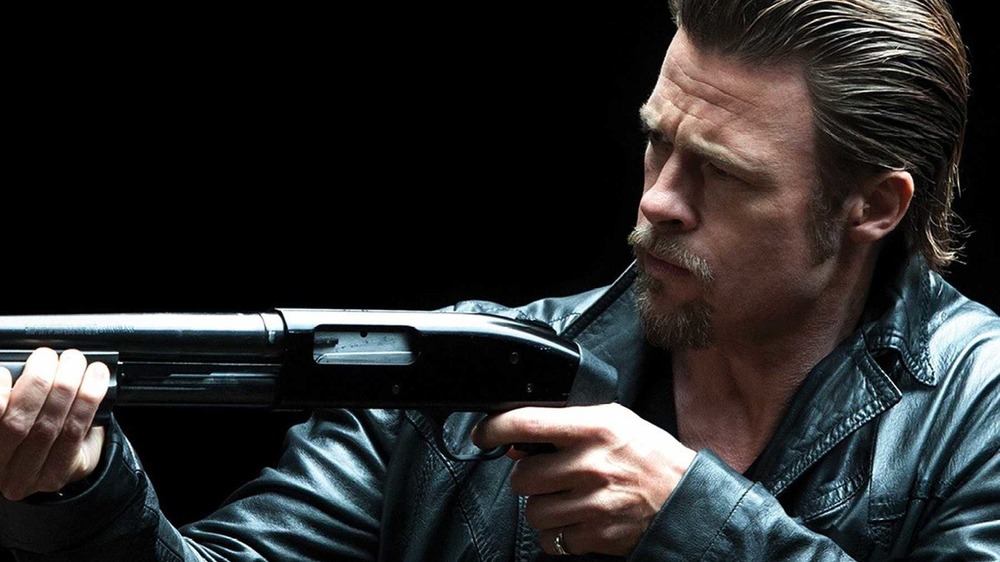

Killing Them Softly with a smoldering Brad Pitt

The 2012 neo-noir Killing Them Softly admittedly doesn't start out soft, but after the first incident in which three characters pull off an amateur heist that leads to their ultimate targeting by the mafia, the fuse burns slowly. The cadence of the movie stands in direct opposition to the style of killing espoused by Brad Pitt's character Jackie Cogan, who speaks the words of the film's title.

Jackie prefers "killing them softly," from a distance and with no warning, so that there is no time for the victim to experience fear or pain. The film, however, takes the opposite approach, stringing the audience along as it takes advantage of Pitt's natural talent for slowly-smoldering intensity.

The window we get into Jackie Cogan's "philosophy" behind killing is an uncommon one in more high-profile crime thrillers, and it reflects the care — and time — director Andrew Dominik takes in delving more deeply into the realities of society, as well as its members whose clandestine dealings and high-octane, aberrant lifestyles often keep such insights opaque to audiences who lead more mainstream lives.

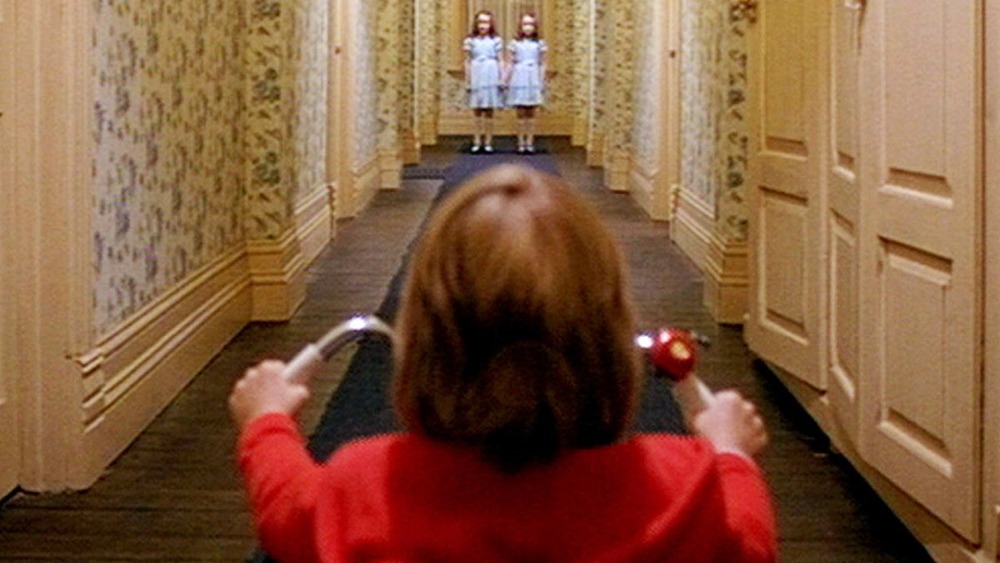

The Shining slowly gets under your skin

The protracted descent of Jack Torrance into madness is what makes the 1980 horror film The Shining iconic in the genre. There are numerous moments designed to jar viewers throughout the film's lengthy 144-minute runtime, like the classic twin-girls-appearing-in-the-hallway gimmick or the famous point at which Jack hacks through a door with an axe snarling, "Heeeeere's Johnny!" at his fleeing family.

But unlike other horror films, The Shining doesn't primarily rely on regular jump scares. Instead, Kubrick establishes mundane visual motifs and places them at intervals, such as Danny Torrance riding his tricycle down the halls or long shots of the Overlook Hotel. These and the infamous intertitles, which outline increasingly shorter segments of time, add some of the only syncopation to the unbalancing monotony of isolation.

As Jack devolves, so does the notion of time: The title cards begin specifying particular moments without a larger context. "4 pm," reads one title card, but on what day? We suspect that the latter parts of the film take place within the same day, but there is no way to be sure. The unmatched suspense that keeps us engaged derives not only from not knowing what's going to happen or when, but from not really knowing when anything is happening at all.

Drive takes you on a leisurely trip

Though Ryan Gosling's taciturn getaway driver sure speeds around, the pace of his story in 2011's Drive is much more measured. Gosling's character remains unnamed throughout the film, credited only as Driver, and the plot development is in many ways just as withholding. While the tale is peppered with incidents of gang violence, the central element of the narrative is, ironically for a character with no name and only rarely a voice, the complexities of the relationships that Driver develops.

Both the romantic and action elements of the story seem subdued on purpose, like the low hum of an idling engine before a getaway car takes off. What separates this film from the wider genres of crime and action is that the relationships feel real. Driver's interpersonal connections do not exist simply as plot devices, though they are invariably influenced by the perilous circumstances of his life. Because of the time the film takes to develop this unnamed man and his motivations, the stakes of survival and revenge are that much higher because we, Driver, and those he cares about are all in the same car.

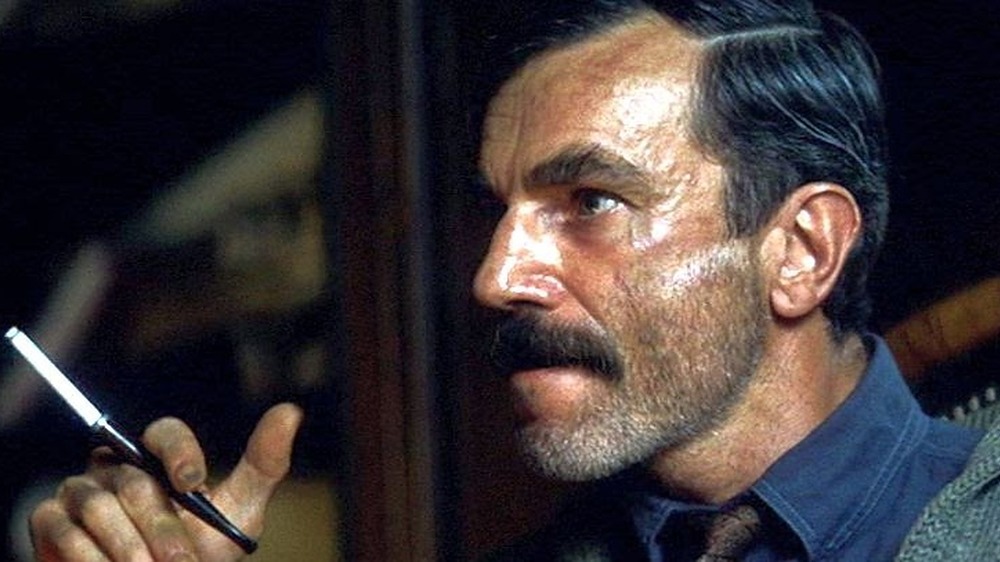

The simmering horror of There Will Be Blood

The operative word in the title of Paul Thomas Anderson's 2007 oil boom period piece There Will Be Blood is definitely the word "will." The level of suspense is so high that fans and reviewers have called it a horror film, which may appear an odd designation for the complex series of relationships and incidents that define the life of ruthless, but sometimes inexplicably sympathetic, prospector Daniel Plainview.

The "horror" arises from the haunting complexities in the development of Plainview, whom Anderson told American Cinematographer magazine was partially modeled after the archetypal figure of Count Dracula. "I just had it in my head, underneath it all, that we were making a horror film," he admitted, comparing Plainview's story to that of a car crash from which we just can't look away.

Unlike a car crash, though, Plainview's story unravels slowly as we drill "underneath it all" for the horrors of the human psyche. The final conflict between prospector and preacher is years in the making, and delivers spectacularly on the titular promise.

2001: A Space Odyssey spans all time and space

Few fires burn more slowly than the flames of civilization across the eons of the universe. For the first several minutes of Stanley Kubrick's 1968 science fiction masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey, there is no dialogue whatsoever as the landscape of early Earth unfolds. To say that the film escalates slowly is an understatement: It begins before the human race evolved and extends to an indeterminable time in its distant future.

For a film that condenses the history and future of human civilization and beyond into 142 minutes, 2001 takes its time, capturing the astronauts, whose story the bulk of the film tells, with beautifully executed slice-of-life shots.

Sufficient tension and mystery (thank you, homicidal but well-meaning HAL-9000 computer) keeps the audience interested until the final sequence unfolds. Astronaut David Bowman travels through a multi-dimensional gate in space and time into a vastly accelerated life-death-rebirth cycle: transformation as a metaphor for human transcendence. The film's unique pace allows its audience to transcend time in its own way as well.

Rosemary's Baby keeps you awake with fear

The suspense of pregnancy can be overwhelming: Will the child be a boy or girl? Will the baby be born healthy and on time? Is your infant secretly the spawn of Satan placed in your womb supernaturally through the efforts of a malicious coven of witches that includes your neighbors and your husband?

There's no "what to expect when you're expecting" book to guide the titular mother in 1968's Rosemary's Baby through such a pregnancy, and the film itself turns a new page on traditional expectations of psychological horror to create something truly unique from conception to climax. As Variety noted, the film "holds attention without explicit violence or gore." In fact, the most violent part of the movie occurs within the first few minutes, when a young woman and new friend of Rosemary's named Terry falls to her death from a seventh-floor apartment.

The death of Terry, a recovering drug addict taken in by Minnie and Roman Castevet, sets the stage for their involvement with Rosemary and her pregnancy, culminating in a gripping psychological tug-of-war that reveals them as members of a Satan-worshipping coven.

Rear Window shows only what Hitchcock wants you to see

Alfred Hitchcock is known as the Master of Suspense, a prolific filmmaker with a penchant for deliberate, systematically executed thrillers that never failed to get under the skin of the audience. His films do not shy away from the more violent or classical aspects of genres like horror, instead using them to augment the creeping, psychological peculiarity at the core of his films.

In 1954, Hitchcock put on one of his best displays in Rear Window, which film criticism luminary Roger Ebert called "the thriller equivalent of foreplay." The scope of the exposition, in large part limited to what we can see through the eyes of the wheelchair-bound protagonist who believes he has witnessed a murder through his rear window, makes the audience painfully aware of the slow-burn pace.

This precise execution creates a sense of suspense that borders on desperate impatience. The audience, like Jeff, feels as though it is trapped, and feels a profound sense of release when the pieces come together in the final confrontation. Though Jeff does get pushed (non-fatally) out of his window during this climax, the moment symbolically puts the "free" in free-fall.

Winter's Bone takes its icy time

Life in the isolated rural society shivering in the Ozarks of 2010's Winter's Bone demands a lean, economical approach to survival. Director Debra Granik, who adapted the film from the eponymous 2006 novel by Daniel Woodrell, takes this practice to heart in the construction of her film as well — a movie that, as Roger Ebert puts it, "doesn't live above these people, but among them."

The dialogue is often as sparse and unforgiving as the landscape into which it is spoken, but a little goes a long way as we watch Ree Dolly, played by Jennifer Lawrence, desperately try to track down her estranged father (or his remains) in order to satisfy the bail bondsman. More than simply a study in the character of a region, Granik orchestrates what is essentially a take on noir with the typical urban element subverted. Ree searches for answers in true detective fashion, tracking down leads sequentially through characters who each add a unique layer of acute tension and overall complexity.

Taxi Driver is a slow ride to hell

One of the most common elements of these slow-burn films is that of a complex protagonist, often an anti-hero, whose questionable choices and motivations don't quite neutralize the allure of rooting for them. A purposefully paced movie is the perfect opportunity to explore the nuances that might be overlooked in a more fast-moving, action-packed film where a more traditional protagonist thrives.

While Martin Scorsese directs Robert De Niro impeccably in his character Travis Bickle's infamous spiral into madness, 1976's Taxi Driver is more than just a case study in the sneaky nature of insanity and obsession, which is where the parallels often drawn between Scorsese's film and 2019's Joker originate from. Taxi Driver does not conflate inner insanity with outer. Rather, as global as it is deeply individual, the film plays upon the inextricable nature of the two, exploring themes ranging from existentialism to corruption through the lens of a taxi driver growing increasingly disillusioned with the human condition . . . or maybe just his own life . . . or both.

The Witch gradually casts its shocking spell

There are only a handful of jump scares in The Witch, a folklore-inspired period horror film from 2015 and the first feature directed by Robert Eggers. It follows a family banished from a Puritan community for religious dissent, and their encounters with a demonic force in the woods near their isolated dwelling. The suspense builds slowly and steadily to a horror more intimate than supernatural.

One of the biggest jump scares comes when a witch appears inside the shed where William has locked his children, but this moment serves almost as a red herring for the true showdown, which comes the next morning when eldest daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) must tearfully kill her own mother in self-defense.

This pivotal moment highlights the fact that much of the suspense revolves not around the family's fear of the occult, but their fear of each other. Their devout religious convictions would have them believe that evil lies within, that "natural" original sin is more threatening than anything "supernatural." The film slowly builds up the dynamics between Thomasin, her siblings, and her parents in order to eventually tear them all down, a destructive collaboration between humans and their demons.

It takes a while to unlock the mysteries of Chinatown

Six years after the release of Rosemary's Baby, Roman Polanski directed another chilling feature remarkable for its premeditated sense of pace as a vessel for an intense plot. The screenplay by Robert Towne is often cited as one of the best of all time, a master class in structure and characterization.

It is no wonder that the film takes so much time and care in its storytelling, because the script is multi-layered and complex. Inspired by the California water wars of the turn of the 20th century, a series of conflicts between the interests of the agricultural community and the city of Los Angeles over water supply, the film is rife with subterfuge both political and personal. Family and marital history exposes elements of political conspiracy only for the reverse to transpire.

In fact, the film packs in so many clandestine themes that it's a wonder it is not more rapid-fire.

The Lighthouse keeps its terrors in the shadows

Robert Eggers strikes again with his 2019 psychological horror film The Lighthouse. The "slow descent into madness" theme should sound familiar by this point, but doing it well is still an impressive feat. Every one of the film's 109 minutes, telling the story of an aging lighthouse keeper and his apprentice, is steeped in disconcerting mythological and psychoanalytical imagery that is in turns violent and erotic.

The personal demons of the two men spur them toward madness, aided, it seems, by some sort of supernatural force present on their remote island. The 1.19:1 aspect ratio is our window into hallucinations and morbid flashbacks on the part of Robert Pattinson's Ephraim Winslow, and alcoholism and obsession on the part of Willem Dafoe's Thomas Wake, who is infatuated with the light over which he keeps watch and believes that seagulls house the souls of reincarnated sailors.

The Lighthouse is unique in that the gathering delusion, while individual to Winslow and Wake, is so magnetic because it's also shared. The exacerbating nature of their relationships to each other and themselves, exposed through dilatory vignettes by lantern-light, causes their mental state to spiral downward exponentially like a wild tumble down lighthouse steps.

Enemy will have you seeing double

You've heard of self-obsession, but Jake Gyllenhaal's character(s) in 2013's Enemy explores this concept, only slightly removed: Gyllenhaal's opening character Adam discovers an actor named Anthony who appears to be his physical double (even down to their scars) and begins to stalk him. After a tense encounter, Anthony returns the favor. The apprehension and hostility grow as the two become more and more involved in each other's lives, Anthony with seemingly more malicious intentions as he conspires to take advantage of the unique vulnerability of sharing your physical identity with another.

Enemy doesn't spend precious time answering questions, like whether the duality is simply the tortured psychological invention of a man having an affair. Instead, the film's surreal tone presents a slow but dizzying puzzle of the subconscious as freely absurd as the furthest reaches of our minds. We don't often think of identity as a form of intimacy, but director Denis Villeneuve and Gyllenhaal urge us to question that.

Parasite is a classic bait and switch

The 2019 black comedy Parasite develops so temperately that for most of the film, viewers may wonder why it is also classified as a thriller. As the struggling Kim household attempts to convince the affluent Park family that each of them are unrelated professionals coincidentally linked through a network of recommendations for employment, the film appears to be not so much a thriller as a quirky yet bizarrely insightful portrayal of class divisions. The "thrills" are more zany than high-stakes.

Then, with only a fraction of the 132-minute runtime to go, the intensity ramps up, jolting the audience unceremoniously out of a manufactured sense of security. We (too late for the impending whirlwind) only realize we have been conditioned when the Kims discover the former housekeeper and her husband subsisting in the Parks' basement. What amounts to a turf war ensues in two parts, first a violent false climax between the two families, then a bloodbath between the interests of all on the idyllic occasion of a birthday party.

Both versions of Suspiria take their time to terrify you

The original 1977 Suspiria left some incredibly large dancing shoes to fill on an empirically-proven difficult stage for remakes, from the alluring glow of the iconic red lighting to the aversive gore of the film's many deaths. Though Rotten Tomatoes notes that it's "not for everyone," the fact that Luca Guadagnino's 2018 reimagining is more polarizing than its predecessor is an achievement in itself. It is more homage than remake, paying tribute, and shining on its own, by deliberately subverting some of the original elements.

Instead of starting out saturated like the original, the more recent iteration opts for muted tones that make the climactic scene all the more striking. Beyond aesthetics, the film's approach to suspense is completely upended: In a visceral early scene, the undercurrents of witchcraft at the dance academy are exposed nearly right away. While the original film takes its time illuminating the evil behind the scenes, concluding only moments after the coven is confirmed to the audience and protagonist, the modern interpretation lays the groundwork early so that it can take its time choreographing a much deeper lunge into the coven's machinations and more fully develop Susie (Dakota Johnson) for the role she will play in them.