The One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest Ending Explained

In the decades since One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest debuted in 1975, it's become widely accepted as one of the greatest movies of all time. Also one of the most well-regarded book-to-film adaptations in cinematic history, the screenplay honors Ken Kesey's original '62 novel of the same name, even with some fairly significant changes.

The film centers around the Oregon psychiatric hospital ward overseen by the nefarious Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher), who shepherds her charges in the most oppressive and damaging way possible. In walks Randall Patrick (Mac) McMurphy, a con man faking insanity to avoid incarceration, who locks horns with Ratched and becomes hellbent on causing an uprising among the patients in the ward. Unbeknownst to him, more dangers await him in the hospital than he ever faced during his numerous prison and work farm stints.

Throughout the film, viewers get a realistic look at some of the inhumane treatment psychiatric patients faced at the time — some of which is sadly still prevalent today. Mental health care is still a widely underfunded and misunderstood field that often leads to mediocre and sometimes damaging care.

Given the film's mental health and treatment themes, the ending can be hard to understand without knowledge of the time period, the history of abnormal psychology, and the analysis of the many symbols the movie incorporates. So who is this Mac character, and did his revolution actually make a difference? What was Chief trying to accomplish in his final scenes? And how does Nurse Ratched represent women in the 1960s? What does it all mean? This is the One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest ending explained.

Who prompted Billy's death?

Content warning: Death by suicide.

Billy Bibbit (Brad Dourif), the soft-spoken boy with suicidal ideations, doesn't just die by suicide in the film: Ratched coerces him into it. When Mac throws a party on the ward with two sex workers, he encourages Billy to make his move on Candy (as he'd expressed interest in her during the boat trip). Candy (Mews Small), who's likely used to her clients treating her like garbage, seems genuinely flattered when Billy stutters out compliments, and their excursion in the supply closet appears to be more than just a job. But that doesn't matter to Nurse Ratched.

Ratched knows precisely what she's doing when she eviscerates the self-confidence that Mac has been trying to bolster in the young man, making him feel shame for his actions. Instead of addressing the situation in any healthy or helpful way, she threatens to tell his mom — and the dam holding back Billy's self-loathing breaks. As someone who likes to get a rise out of her patients during therapy, Ratched delights in setting off the conditions that landed him in the hospital to begin with.

While her end goal may not have been for Billy to die, she knows her manipulation will finally set Mac off and allow her to regain some semblance of control over the ward. To her, Billy's suicide is a casualty to get what she wants: A reason to lobotomize McMurphy, and to use Billy's death as an example of what happens when you rebel. Billy deserved better.

Sex is punishable

Every time someone has sex (or mentions it) in the film, the characters in Cuckoo's Nest get punished, whether it's on the ship when Mac goes below deck with Candy and the patients panic and almost crash the boat, or the way Ratched gets manipulative and hostile any time someone brings up sex during group. In Billy's case, his punishment is death when he loses his virginity to Candy.

This is an outdated TV and film trope that is especially prevalent during periods when society frowns hardest upon expressions of sexuality. In 1963, when the film is set, the hippie movement was just beginning, continuing through 1975, when the film debuted. Along with the idea of peace and making strides to end the Vietnam War, embracing sexuality was a huge aspect of the movement — which was one reason some other parts of society shunned the hippie lifestyle. Characters like Ratched, who are completely unwilling to embrace change, represent the idea that sexuality or promiscuity are punishable, reflecting a major bias of the time (one that still continues today).

Patients fall victim to the system

At the end of the film, Ratched wins and Mac loses. Chief represents the one small victory that McMurphy's attempt to liven the ward brings, but everyone else falls right back in line with the status quo that Mac desperately tried to change.

No one fights back, and Ratched uses electroshock and lobotomies as weapons rather than cures. Sefelt says after Mac has been missing for a while, "McMurphy has escaped. They were taking him through the tunnel. He beat up two of the attendants and escaped." When Mac disappears after attempting to strangle Ratched for her role in Billy's suicide, it's easier for the patients to delude themselves into thinking that Mac escaped. This way, they can continue revering him as a legend. It's comforting that escape is possible, even though they don't plan to do it themselves.

When Harding assures Sefelt that Mac is upstairs getting punished, he and the rest of the patients are quick to deny, and everyone's asleep when the orderlies drag him back to the ward after his lobotomy. In the film, it's unclear if the rest of the ward even finds out what really happened to Mac, but when the credits roll, Ratched and her dominion over the ward have won. All the patients except Chief are still there, and Mac's revolution was largely for nothing. The idea that the patients have no control over what happens to them is underscored by the ending, and the hospital hasn't helped anyone.

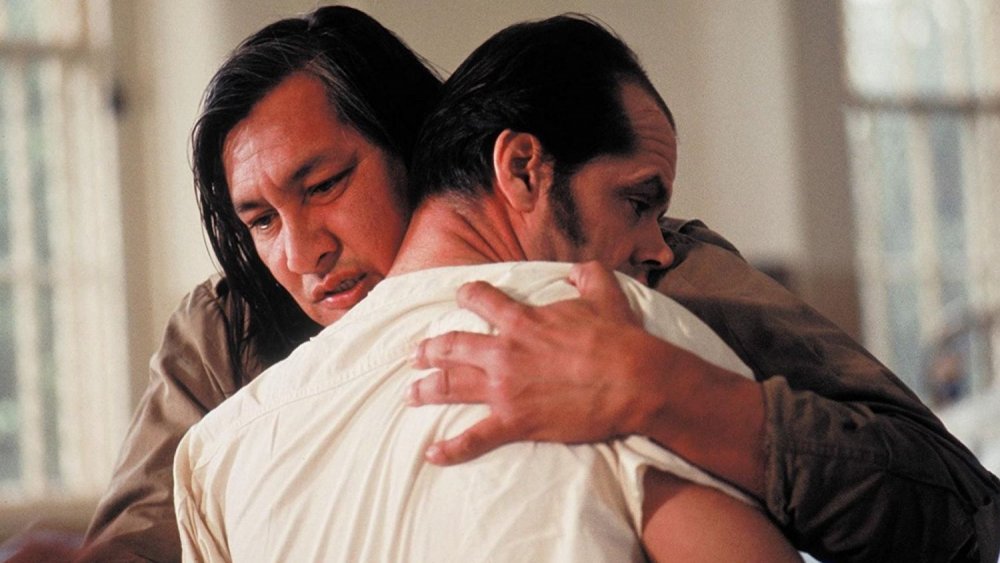

A heartbreaking mercy kill

Out of all characters on Ratched's ward, McMurphy impacts Chief the most. By watching Mac refuse to take anything lying down, Chief learns how to be as "big" in his actions as he is in stature — and he feels like he owes that to McMurphy. Without the con man giving him the confidence to talk and break free from the ward's toxic environment, Chief would still be silently sweeping the hospital floors at the movie's close. Chief knows that someone like McMurphy — who is so full of life — would never want to live after being lobotomized. Being a prisoner on Ratched's ward was hard enough for Mac without being a prisoner in his own body.

Chief understands that feeling better than most, as he lived for years silently taking insults, cut off from socialization, and going through the monotonous motions without feeling like he could be himself. Witnessing McMurphy forced into that type of existence is too much for Chief. After a goodbye hug, Chief makes the choice he believes McMurphy would make for himself by suffocating him with a pillow. The scene is hard to watch, as Mac's body involuntarily fights back. But Chief succeeds, and he finally feels like he's done all he can do on the ward, later escaping Ratched's reach. Whether he did the right thing or made a call that wasn't his to make is up to the viewer.

Chief honors Mac

Mac's entire existence in the ward represents freedom and self-empowerment. While his presence in the film version of the story doesn't have the long-term impact on most patients than he would have liked, his refusal to give up and his quest for freedom fuels the plot. There are several ways that Chief can escape the ward, but he picks the most dramatic way possible — and Mac would have loved it.

When McMurphy tries to pick up the control panel in the tub room earlier in the film, he fails, but he still makes an almost ridiculous effort to move it. While he's red and out of breath from his pointless attempt, he says "But I tried, didn't I?... At least I did that." In Mac's opinion, no one in the ward ever does anything to help themselves or change their situation. And at this point, he doesn't have a firm grasp on the risks involved with patients standing up for themselves (which he sadly learns), but amid his schemes to swindle them out of money, he does care about his fellow patients.

As one final way to honor his fallen friend, Chief succeeds in ripping the control panel off its stand, chucking it out the window to make his escape. He reaches the freedom Mac strived for while trying something new and succeeding. Even if he failed, Mac would have been proud that he tried, but Chief finally felt "Big," and he acted on it.

Ratched faces no consequences

Despite directly playing a hand in Billy Bibbit's suicide, Ratched faces no consequences for her actions — including lobotomizing a patient whose crime was lashing out the woman primarily responsible for the death of his close friend. Ratched's victory in the ward highlights the stigma that surrounds mental health patients. A larger problem in the mental health industry, even today, is the failure to listen to and respect psychiatric patients, who deserve to have a say in their care.

Earlier, Ratched throws a fit when McMurphy dares to ask which medicine the orderlies are giving him. But anyone has a right to know what they're putting in their bodies. It's the staff's job to work with the patients to determine, as a team, what medicine is helping, if the medication is doing more harm than good, or if the side effects are too much to bear. Instead, she just threatens them if they ask questions, whether the pills are helping or hurting.

Ratched has the entire ward hardwired to do her bidding, and no amount of patient lobotomies or deaths seem to lead her to face any kind of reckoning. Because who is anyone going to believe? The decorated war nurse or the psych patients? The situation underscores a major problem with mental health care.

Cuckoo's Nest demonizes successful women

Nurse Ratched may not be the ward's doctor or anyone with a significant level of authority, at least on paper. Yet she manipulates the staff through fear just as much as she plays god with her patients. No one stands up to her, even when they can see that there's something wrong. Ratched holds all the cards for who gets released and who gets life-altering procedures: Nothing on the ward happens without her say-so.

It wasn't until the feminist movement in the '60s that working women in the U.S. rose to significant numbers. While a significant number of single women were in the workforce in 1930, only about 12 percent of married women worked. That number rose to about 50 percent by 1970. After picking up various jobs while men were serving in World War II, married women found purpose in employment, and many fought to keep working after the war ended and their husbands returned. Many men weren't thrilled with this and campaigned to keep "women in their place" as homemakers. Given this stigma, it's not a shock that the film depicts working women in a harmful manner.

With the context of the time period, fans can interpret Ratched's power-hungry manipulation of the ward as a fearmongering depiction of all of the awful things that can happen when a woman is in charge. Patients frequently accuse Ratched of taking away their manhood when they rant to each other — a point further driven home by the shot of Ratched smiling after forcing Mac into a lobotomy.

Lobotomies in real life and Cuckoo's Nest

Imagine getting a Nobel Prize for inventing a procedure that would go on to leave 50,000 patients in the U.S. alone either dead or virtually comatose, with very few "successes.'" Egas Moniz held that honor in 1949 when he modified earlier attempts at brain alteration procedures to create the leucotomy. One year later, Walter Freeman took the surgery to the States, renaming it the "lobotomy" and using what was essentially an ice pick to go through the eye instead of drilling through the head. While it looked a lot less messy, the results were the same. Often touted as a "miracle cure," the horrific procedure forced on McMurphy at the end of the film was supposed to help patients control their emotions. Spoiler alert: It mostly took them away entirely.

In an interview with Life Science, medical historian and NYU Langone Medical Center professor Dr. Barron Lerner described the procedure, referring to the after effect as "mental dullness." He noted that most patients "could no longer live independently, and they lost their personalities." The doctor explained that doctors could maintain control of overcrowded wards by handing out lobotomies to unruly patients: precisely what happens to McMurphy. Lerner praised One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest for its accurate depiction of the procedure, noting that movies tend to exaggerate things like this, but that the portrayal in Cuckoo's Nest is "disturbingly real."

Why the subject of lobotomies still mattered

While the novel takes place in the '50s, the movie is set one year after the novel was released. The book debuted during the height of the lobotomy's acceptable use, while the film is set just as hospitals were phasing out the procedure. Walter Freeman performed his last lobotomy in 1967, five years after the film takes place. By the time the movie was released in 1975, he'd been dead for three years. So why was this story still important to tell?

Writer Ken Kesey's time working as a nurse's aid at a psychiatric ward at a veteran's hospital in 1960 inspired the idea for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. That same year, Dr. Freeman performed a lobotomy on the youngest patient ever to receive one — a 12-year-old boy named Howard Dully. Luckily, Dully survived the procedure with his motor and speaking functions intact, growing up to become a bus driver.

As reported by NPR, Dully said, "If you saw me, you'd never know I'd had a lobotomy." He followed up the statement with a chilling sentiment: "But I've always felt different — wondered if something's missing from my soul." According to his father, before getting the lobotomy, Howard's stepmother tried multiple doctors before finding Freeman. They all told him he "was a normal boy." Unmoved by their answer, she sought out a doctor who changed the child's life forever.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest tries to change a broken system, even now

Lobotomies were dwindling by the time Kesey wrote the One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest novel, and were banned in the U.S. when the film was released, but the message was clear. Far too many patients are subjected to life-altering procedures in psychiatric wards — and both families and facilities have far too much say in forcing patients to undergo irreversible procedures they don't want.

We see it when Ratched manipulates Billy with details she shouldn't share about his care, even to his family. We see it when the nurse forces Mac into electroshock and a lobotomy. We see it in the way the hospital staff uses fear of these procedures to control the ward. We see time and time again that staff cares more about power and dominance than the patients' actual health. The shock of how cruel and ineffective the lobotomy "treatment" was adds a poignant and powerful ending to get readers and viewers to care about mental health and poor treatment ramifications.

Hospitals still face massive overcrowding. Patients often have to wait days, weeks, or even months for a bed in a ward or even an appointment — even for severe cases of suicidal ideation and conditions like schizophrenia. While the lobotomy has been outlawed in the States for decades, a modern version called psychosurgery is still performed (albeit rarely) today. Mental health care has come a long way since the '50s. However, there's still more work to do.