The Real-Life Tragedy Behind Twilight Zone: The Movie

In 1983, fans of Rod Serling's classic TV series The Twilight Zone got an unexpected treat: a big-budget feature film revival, made up of four segments directed by the absolute hottest directors of the day (or any day, really). The flick is still regarded warmly for its many delights, not the least of which was its killer prologue, featuring Dan Aykroyd and Albert Brooks as motorists on a stretch of lonely road late at night. Three of its four segments were remakes of classic Twilight Zone episodes, and two of those can safely be singled out as among the scariest, most bizarre stories to ever appear in a PG-rated movie: you had Joe Dante, right smack in between The Howling and Gremlins, offering up his take on the all-powerful, malevolent little boy from "It's a Wonderful Life," and Mad Max director George Miller putting John Lithgow through the terrors originally experienced by William Shatner in "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet." Oddly, the only segment that failed to land was the one directed by one of the film's producers, the great Steven Spielberg — a retelling of the little-remembered episode "Kick the Can."

The first segment was the only one to tell an original story, and it, too, was helmed by one of the movie's producers and its driving creative force, An American Werewolf in London director John Landis. Unfortunately, that segment would become the basis for one of the greatest tragedies in the history of the motion picture industry — one that carried ripple effects which linger to this day. This is the story of the real-life tragedy behind Twilight Zone: The Movie.

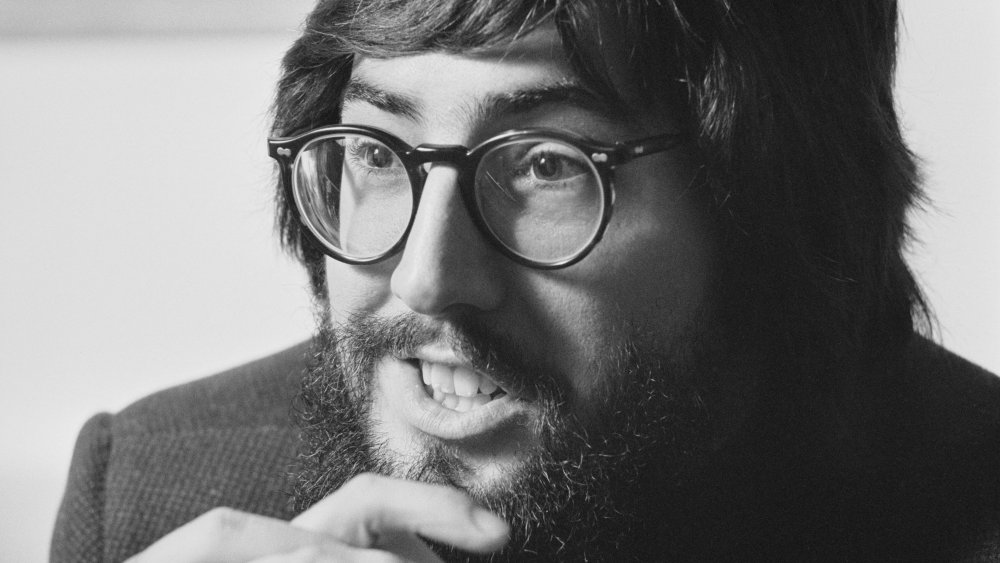

The fateful segment starred Vic Morrow and was directed by John Landis

Landis also wrote the original story for his segment, titled "Time Out," and for his lead actor, he went with old school Hollywood star Vic Morrow — who was known for playing tough guys like mafioso Dutch Schultz in 1961's Portrait of a Mobster and Sergeant Chip Saunders on the ABC drama series Combat!, which ran for five seasons from 1962 to 1967. Morrow was a perfect fit for the role of Bill Connor, an unrepentant racist first seen making his friends extremely uncomfortable with a drunken rant in a bar. Bill has had a rough day; he was passed over for a promotion at work in favor of a co-worker who, of course, happened to be Jewish. But when he leaves the watering hole, his night gets a heck of a lot worse.

Bill suddenly finds himself in WWII Germany, pursued by a pair of SS officers intent on detaining him for the crimes of not having any papers and not speaking German. He narrowly escapes — only to find that his circumstances have not improved, as he's now a Black man in the Jim Crow South. After another detour through Vietnam, in which he's fired upon and pursued by American soldiers who see him as a Viet Cong, Bill's nightmare journey ends where it began — in Germany, where he's being hauled off to a concentration camp in a packed boxcar. As the train pulls away, he realizes he can see the bar he'd left earlier outside, and his friends looking for him... but they can't see him, nor can they hear his pleas for help. As it often is in the Twilight Zone, justice was served with a heavy dose of irony for Bill Connor — but that wasn't the way the segment was supposed to end.

Vic Morrow and two children were killed in a gruesome accident on set

The segment was originally to see Morrow's character redeemed by a heroic act of rescue: saving two Vietnamese children caught in the midst of a bombing raid by American forces. The key scene involved Morrow racing through a shallow swamp in a mocked-up Vietnamese village, pursued by a helicopter, with a child under each arm: young actors Renee Shin-Yi Chen, who was 6 years old, and Myca Dinh Le, who was 7.

The filming of the scene took place around 2:30 in the morning, and it utilized a real helicopter, piloted by Vietnam veteran and ace stunt pilot Dorcey Wingo. There are conflicting accounts of what went wrong and how, but what is known is this: a series of special effects explosions were set off in the vicinity of the copter's tail end, which damaged both of its main rotors, and caused the rear rotor assembly to become completely disconnected. As the horrified crew looked on, the copter began to spin and descend uncontrollably; despite his best efforts to rein it in, there was only so much Wingo could do with no rear rotor. A panicked Morrow dropped Renee Chen into the water, and he was reaching out for her when the aircraft landed on top of the three actors. Renee was crushed by one of its skids, while Myca and Morrow were both decapitated by the still-spinning main rotor blades. All three actors died instantly; Landis frantically called for the cameras to stop rolling, and told the entire crew to drop whatever they were doing and go home immediately.

The child actors were hired in violation of California law

There were a number of factors that led to the tragedy, mostly in the form of a series of questionable decisions made by Landis and his producers — the first of which was the way in which the children were hired in the first place. Informed by the film's casting agency, Fenton-Feinberg Casting, that California child labor laws did not permit children to work past a certain hour, Landis was faced with a quandary: completely rearrange his shooting schedule, or find another solution. Perhaps sensing trouble, Fenton-Feinberg soon revised its stance: since the parts in question were not speaking ones, the children would technically be extras, and could not be hired through the agency at all.

Undeterred, Landis asked producer George Folsey to find him two children to use for the scene, and Folsey reluctantly agreed. Since he was circumventing the normal casting process, Landis may have felt emboldened to make another crucial decision: he decided to leave the kids' names off the call sheets, and to pay their parents, who were aware that their children were being employed illegally, under the table. Production assistant Cynthia Nigh would later assert that she heard Folsey crack a joke which rang with ominous foreshadowing: "We'll probably all be thrown in jail for this!"

Some involved had grave concerns about the shoot, including the pilot

On the early morning of the shoot, more than a few of those on set — including Wingo, who, remember, had flown combat missions in Vietnam — expressed their concerns over using pyrotechnics in conjunction with a low-flying helicopter. While capturing a shot that took place just before the fateful scene, a rigged explosion in the water went off too close to Chen for comfort, getting dust in her eyes and causing her to tear up; this caused her father to ask Folsey if the action sequence they were planning would put his child in any danger. "No, not dangerous," Folsey replied. "Just a loud noise."

During the next shot, which was from inside the copter's cockpit, unit production manager Dan Allingham sat next to Wingo in the co-pilot's seat. During that shot, the pyrotechnics were too close to the copter for Wingo's comfort, and he told Allingham to take it up with Landis, which Allingham said he would. On the ground, fire safety officer Richard Ebentheuer was watching, terrified, and he expressed his fears to his superior George Hull. When Hull likewise told Ebentheuer to take his concerns to Landis, Ebentheuer became borderline enraged and actually cursed at his boss, then uttered a dark and prophetic proclamation: "The helicopter will be on the ground!" After landing, Wingo was discussing the heat of the pyrotechnics with assistant camera operator Randy Robinson when Landis overheard their conversation. Smiling mischievously, the director offered a response that was as truthful as it was chilling: "You ain't seen nothing yet."

John Landis and others were charged criminally

The ensuing accident cast a grim pall over the film; while discussions were had about whether to excise the segment altogether, in the end, it was kept. The scene in the Vietnamese village was deleted, as were the onscreen appearances of the children; the narrative was modified through careful editing, and Morrow's skillful performance was a highlight of the finished film when it premiered in theaters to mixed reviews on June 24, 1983. Lukewarm critical notices, though, were the least of Landis' problems.

In 1984, Landis, Folsey, Wingo, Allingham, and special effects supervisor Paul Stewart were hauled before a grand jury which would eventually indict them on charges of involuntary manslaughter, resulting in a trial that began in 1986 and would go on for nearly ten months. The trial made national headlines throughout that year and the next, and it carried grave implications not just for those charged, but for the future of the motion picture industry. It was the first time that a director faced criminal charges for actions taken on the set of a film, and while Landis was adamant that there was no way the disaster could have been foreseen, the testimony of some of those at trial would paint a different picture. In fact, a whole array of different pictures would be painted at trial — for as far as those involved were concerned, there was plenty of blame to go around.

The legal proceedings were a years-long blame game

In journalist Stephen Farber's 1988 novel about the case, Outrageous Conduct, it was noted that one of the critical decisions made by the prosecution would come back to haunt them: they chose not to indict Landis, Folsey, or Allingham for their illegal hiring of the children, crimes of which they were absolutely guilty, in order to focus on their case for involuntary manslaughter. Farber also noted that from the trial's outset, it was very clear that the "above-the-line" defendants, Landis and the two producers, and the "below-the-line" defendants, Wingo and Stewart, were not going to be forming a united front.

All five defendants had their own attorneys, and Landis' tactic of pleading ignorance — essentially saying that his below-the-line employees such as Stewart and Wingo had failed to give him accurate information — did not sit well with the attorneys for those parties. At one point, Wingo's lawyer Eugene Trope bitterly turned on Landis, saying, "The responsible party here is the director-producer, and I think Landis is trying to shift the blame off to anyone and everyone he can." Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge Brian Crahan, who was presiding over the trial, seemed to agree, to an extent. On April 23, 1984, he dismissed the manslaughter charges against Folsey and Allingham, but upheld those against Landis, whom he said "set up, among other things, the combination of circumstances which, in the final seconds of filming, caused death and destruction," as well as Stewart, whom he called "the ultimate arbiter of the special effects," and Wingo, whom he said "knowingly hovered his helicopter at such close alignment to the explosions as to create a known risk of harm to anyone within the danger zone of the crash." Folsey and Allingham were still charged with criminal negligence.

John Landis was anything but contrite during the proceedings

Aside from his relentless casting of blame in any direction but his own, it was noted early and often by journalists covering the proceedings that Landis was not exactly contrite over the whole thing, and in fact often appeared to consider the grand jury proceedings resulting in his indictment and the trial itself as one big hassle. His demeanor before that grand jury was one of impatience and arrogance; for example, when pressed by District Attorney Gary Kesselman as to the chain of command in ensuring that stunt shots with coordinated special effects would be captured safely, Landis insisted that the buck stopped with Stewart and Wingo, who — as "experts" — should have worked out all of the details without the need for him to even be in the loop. When Kesselman pointedly began, "The final authority in terms of camera, actor positions, helicopter, or whatever on that set..." Landis interrupted him with an outburst. "Is not mine!" he shouted. "Because if I ask an actor — [if] I said, 'Would you please take your hand and stick it in this garbage disposal,' the actor is going to say, 'Of course not.'"

Taking the stand during the trial, Landis didn't change his combative approach, insisting that he only hired the children illegally because the shoot would be taking place late at night (and not because he didn't think the labor board would allow him to shoot the scene as planned because of the danger), and that he had believed the shoot to be completely safe. When prosecutor Lea D'Agostino suggested that if that were the case, Landis might have no trouble filming such a scene again, the director simply freaked out, shouting, "I would not film it again!" — while still refusing to concede that the shoot had been inherently dangerous.

The criminal trial resulted in acquittals all around

Amazingly, after months of poring over the details of the horrendous accident and hearing all five defendants blame anyone but themselves, the jury returned verdicts of not guilty on all charges on May 29, 1987. In the end, the twelve jurors appeared satisfied with the conclusion that an unnamed special effects technician — whose immediate superior was Stewart, and who had not been charged — essentially caused the accident by setting off pyrotechnics without first visually locating the helicopter.

The acquittal did not result in Landis suddenly discovering his contrition. The Monday following the verdict, he appeared on Good Morning America to decry his "thoroughly dishonest and political prosecution," and in a subsequent interview with the Los Angeles Times, he called D'Agostino "Grotesque, an aberration. She is very unimportant. What is important is the Los Angeles district attorney's office spending this kind of money pursuing something that they know damn well is bogus."

Steven Spielberg ended his friendship with Landis over the incident

Landis and Spielberg had been associated with each other long before Twilight Zone: The Movie; up-and-coming members of the "New Hollywood" movement at the time along with directors like Martin Scorsese and Brian De Palma, the two were buddies, and had publicly acknowledged their friendship by way of their films. Landis popped up in a small cameo in Spielberg's 1979 war comedy 1941 (which had been a lukewarm financial success and a pretty major critical flop), and Spielberg had returned the favor by appearing in a small but memorable role as a government employee in Landis' 1980 film The Blues Brothers (which had been a smash hit).

Landis' behavior on the set of Twilight Zone, however, broke that friendship for good. Strangely enough, this may have been the case even if the fatal accident had never occurred; it's been reported that Spielberg took serious issue with Landis' use of live ammunition on the set, an egregious safety hazard that was confirmed during the trial.

Careers were destroyed because of the incident, but Landis recovered

As one might expect, the tragedy had serious professional consequences for many of those involved. In a 1988 Los Angeles Times article exploring the aftermath of the accident and trial, Wingo noted that the FAA had tried to revoke his pilot's license, which he kept only after five arduous years of appeals conducted while under a cloud of controversy. Two camera operators, Roger Smith and Stephen Lydecker, saw their careers essentially go up in smoke; Lydecker claimed that he had been pegged as a "troublemaker" for being among the first to publicly suggest that the accident could have been prevented, and Smith shared a similar experience. "It's the same old story," he said at the time. "They all say they want you to be safety-conscious, but if they think you're too safety-conscious, they're afraid of you. There's definitely a double standard in the industry."

Landis, however, landed squarely on his feet. The Times piece was published just a couple months after the release of his smash hit comedy Coming to America (which the Twilight Zone jury had gotten to see a special preview screening of at Landis' invitation, a move that raised quite a few eyebrows), and he would continue to produce and direct for film and television. The Times quoted Desmond Ryan, a columnist for the Philadelphia Inquirer, who pointed out the severity of that double standard Smith had mentioned. "In most walks of life, [the accident] would have led to [Landis'] swift and irretrievable fall from grace," Ryan wrote. "Landis' career has suffered no setback in Hollywood — a town that is historically lenient toward the sins of people whose pictures make money."

The tragedy changed the way movies are made

If there is a silver lining to the tragedy, it's that it probably helped to prevent similar incidents in its aftermath. Warner Bros. executive John Silvia became bent on whipping industry safety standards into shape after the accident, and to that end, he created a committee tasked with creating new standards for the use of aircraft, smoke effects, pyrotechnics, and any other potential hazard that might possibly come into play on a film set. The committee collected these standards into a series of so-called "Safety Bulletins" which eventually became the manual known as the Injury and Illness Prevention Program, which is revised constantly and revisited every time there's an on-set mishap causing serious injury or death (via Slate).

Of course, filmmaking is a tricky and complicated business, and as is the case with many industries, there's probably no way to completely eliminate every possible hazard. But before that horrifying accident on that summer morning in 1982, there were virtually no standards to speak of — and while the tragedy that befell Morrow, Chen, and Le probably could have been prevented, there's no telling how many similar tragedies it ultimately helped to prevent.