Attack On Titan: The Biggest Differences Between The Anime And The Manga Ending Explained

Contains spoilers for "Attack on Titan"

The "Attack on Titan" franchise has finally drawn to a close — for pretty much the third time. The long-running anime adaptation of Hijame Isayama's long-running manga series of the same name wrapped up its epic tale of life during wartime — and giant killer humanoid monster time — in November 2023, with an 85-minute episode that concluded the series that began in September 2013. Both the anime and manga are about the heartache caused by the cycles of so-called "peace" and war — and the moments of love and connection that blossom within that cycle.

The manga's ending in May 2021 created a hotly divided "Attack on Titan" fandom, prompting a public apology from Isayama at Anime NYC's 2022 convention. But would the ending of the anime suffer the same fate? Fans had years to wait and see, along with a promise from Isayama that things would be the same — but different.

Does the long-awaited ending of the anime adaptation stack up to what is, for many, their first and favorite manga? Does it continue to polarize fans? Or does the anime ending improve upon what some have decided is tragic manga perfection, and others see as a rushed, bleak, and nonsensical justification of genocide and out-of-nowhere love stories? Read on to find out, as we rumble through "Attack On Titan," and the biggest differences between the anime and the manga ending explained.

The time skip provides context

A major difference between the "Attack on Titan" anime and manga is how the show tells the ending of the same story. Instead of totally changing major events, the anime provides greater context for the world at war in "Attack on Titan." Though the years-long time skip occurs between the end of Season 3 and the start of Season 4, it provides emotional fuel for the finale.

Four years pass between those key seasons, and when things start back up we see something that changes everything: Life from the perspective of the so-called "enemy." Marley (and the Marleyans) have been Eren and all Eldians' enemies from the jump. But a closer look at the Marelyans' actual lives under tyrannical rule shows that bad guys are in the eye of the beholder. The action after the time skip humanizes the enemy for some of Eren's friends and fellow fighters — but more importantly, for anime viewers.

This new understanding of life behind enemy lines affects the ending of the "Attack on Titan" anime. While both the manga and anime endings are emotionally resonant (and ultimately, kinda bummers), the anime ending's handling of many more minor characters' storylines and the true motivations of Marleyans brings additional poignancy and heartbreak to Eren's final choices — and the new world he leaves to his friends and enemies alike.

The power of dove

The "Attack on Titan" manga was such a hit, readers couldn't wait to snap up new books as they were released. Sometimes they really couldn't wait, and both official production lines and unofficial English scans lost something key in translation. This led to the manga line — and widespread meme — "Eren becomes dove (crying)". As hilarious as this bad translation may be, it also undercuts the point of Eren's possibly literal closing-act transformation in both the manga and the anime.

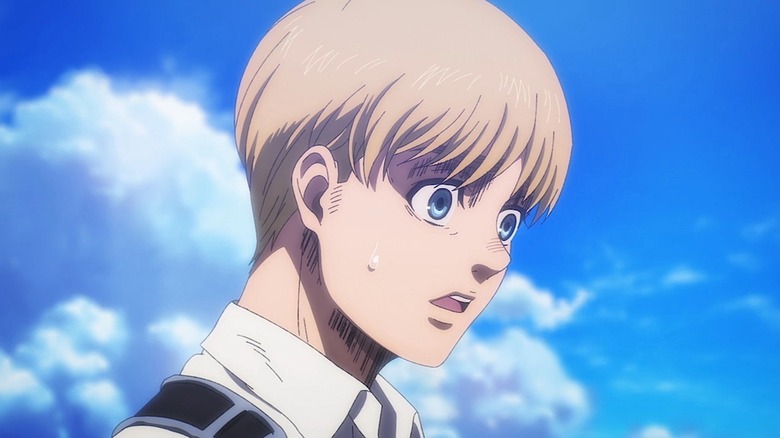

Perhaps because the anime had the manga's translation issues to learn from, Eren's "transformation" into a bird after meeting his end at Mikasa's hand is heartrending in the anime. The episode slips through time (much like the manga) to show Mikasa and Eren's final moments of happiness together, and viewers get a look at what love between than could really be like as well as how it started. We're reminded of the scarf a much younger Eren wrapped around Mikasa's neck to keep her safe.

When Mikasa crashes back into reality, she makes the choice to save what she can of the world rather than her love. It's off with Eren's head — and off with Mikasa's heart. But as Mikasa weeps under the tree over doing what she had to do, a bird appears and wraps her in the scarf one more time. Mikasa is moved, and feels like whatever good left in Eren has manifested for her in this action. The moment has real emotional weight — but as far as memes go, it leaves much to be desired.

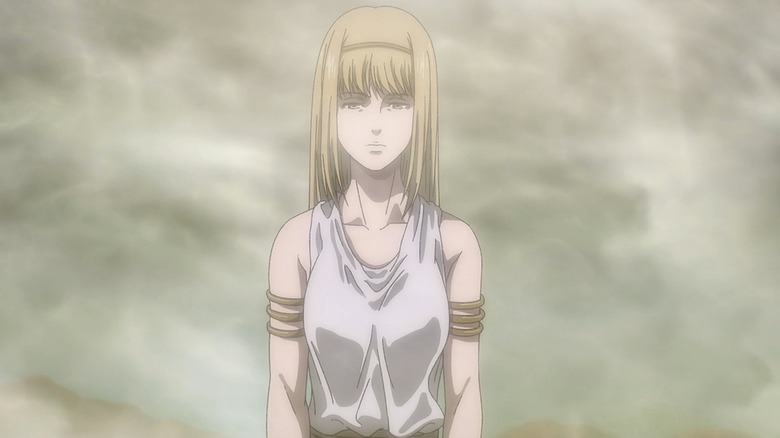

Ymir is still confusing but in slightly different ways

Both the "Attack on Titan" manga and anime tell sprawling stories, with a massive cast of characters. But both iterations of the same story have a deeply broken history at their hearts. In the "Attack on Titan" anime, this rotten root lies in the story of Ymir, and the heartbreaking trap of "love" and abuse with King Fritz.

The ending of the anime shows Ymir in the past, not just being abused by King Fritz, but learning to interpret her terrible treatment as love for him. Because her plans to take herself off the board are thwarted by Fritz, he is able to enslave her and use her powers for destruction. In the manga, Ymir has moments where she makes it clear her "love" for Fritz doesn't run deep, and is an act of survival. But in the anime, the longing and wounded shots of Ymir watching King Fritz with his other lovers really blur the line.

In both anime and manga, Ymir's storyline is delicate and deranged. But in the ending of the anime, a more direct line is drawn between Ymir being unable to break the cycle of abuse and toxic love, and Mikasa. Viewers see Mikasa having the potential to become very much like Ymir, if she chooses to spare Eren out of love. But instead of the cycle repeating through another generation, Mikasa slays Eren. While this leads to an epic smooch with his severed head, it also is shown to give Ymir a sense of freedom — even if only in flashback.

The 10 Years scene is played more for heartbreak

Let's not mince words: The "Attack on Titan" manga had so much story to tell, and so quickly, for a ravenous empire of fans — that maybe some things got rushed in the process. One such storyline, per many fans, is the love story angle of Eren and Mikasa. While always hinted at in both manga and anime, the anime version of their love story feels a little less breakneck than in the manga. The ending of the anime also reframes what, for many, came off as big-time incel vibes in the manga.

One of the most pivotal scenes in the ending of "Attack on Titan" in both the manga and anime is the final conversation between Eren and Armin Arlert. The friends have been through hell and back, and so has Mikasa. But when Armin asks what kind of life Eren wants for Mikasa after he's gone, Eren's rageful response is confusing. Was he grieving? Behaving like a spoiled brat? Or a heartbroken boy on the verge of self-mockery?

In the anime, Eren's frustration is more clear – he hates that he is a "slave to Freedom" and that his genocidal tendencies mean he can't get the girl. It isn't that he hates the girl himself, and his hope that Mikasa never moves on from him — at least not for 10 years — is vocally and emotionally played clearly as a heartbroken boy who knows he is helpless to lose everything. A heartbroken genocidal maniac boy, but still.

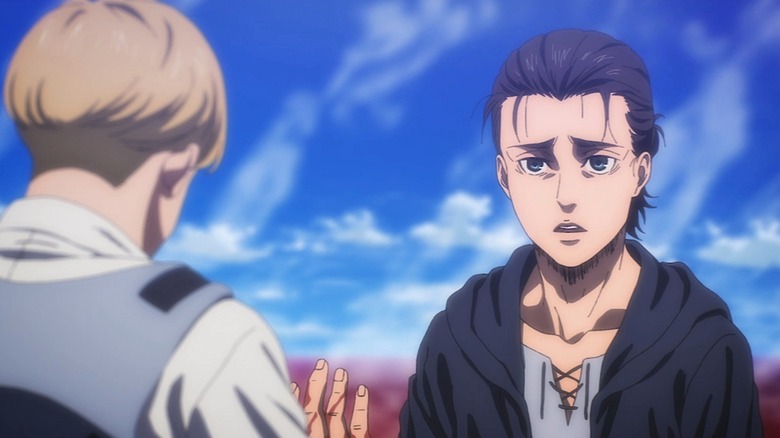

Armin thinks the Rumbling isn't the way

The big conversation between Armin and Eren at the end of "Attack on Titan" is a key scene in the ending of both the anime and manga. A lot of micro-clarifications were made in the anime ending to make up for the disastrous way the manga was received. The most clear-cut difference in the anime and manga version of this conversation between the two friends and broken warriors is that Armin actively, clearly disapproves of Eren using the Rumbling in the anime story.

Genocide is one of the worst evils there is, and "the Rumbling" is a disturbingly soft name for it. Both the anime and manga of "Attack on Titan" go to great (and often confusing) lengths to explore why Eren feels pushed to commit such an act, and what the stakes are for it. Those stakes change in both versions of the story, but the most clear change in regard to the Rumbling is Armin's full-throated disapproval of it in the anime.

In the anime, Armin points out that genocide isn't going to solve their problems or stop war forever. Eren also admits his own plan is basically the worst, but he hasn't been able to come up with better options. Armin is furious with this, which is a big difference from his contradictory — even conciliatory — reactions in the manga.

An important thank you is significantly different

The major differences between the ending of the "Attack on Titan" anime and the manga aren't the result of drastically different scenes or all-new storylines. The most significant changes in the anime story come from minor adjustments in dialogue and tone, and this is never more emotionally impactful than in the final anime conversation between Armin and Eren.

Whether memes, bad bootleg English translations, or imprecise writing are to blame, Armin's line thanking Eren for massive genocide didn't sit well with most readers of the manga. In the manga, Armin ultimately seems to thank Eren for doing the Rumbling for the sake of his friends — so they can be seen as heroes and live in a time of peace. While a generous reading can take this manga line as Armin forgiving his friend for his atrocities because he knows Eren is doomed anyway ... it still reads rough.

The anime shifts Armin's thank you to Eren to be more about showing him what life beyond the walls could be like — literally and figuratively. This is done in heart-wrenching visual style in both forms of the story, but the anime version also features powerful voice actors whose hearts are breaking in the moment. Armin thanking Eren for showing him what could be possible in their world, both good and bad, is perhaps more in line with Isayama's original intention for the scene, and a sign of growth for all the artists involved in making it.

Armin's guilt is expanded in the anime ending

It's hard being the bad guy in an epic series. "Attack on Titan" is full of characters to care about and stories to tell, but at the end of the day, it's Eren's story. Whether you consider him a villain or a tragic hero, Eren does a lot of terrible things in the series — but he doesn't do them alone.

The manga doesn't make a head-on admission of this, but the ending of the anime sort of does. The change occurs in another small exchange within the key scene of Armin and Eren's final talk. Eren weighs the full horror of what he has done in an attempt for freedom — and also because, apparently, he wants to. It's a lonely moment, and instead of letting him bear it alone, Armin admits he is responsible for some of those terrible acts himself — and that Eren isn't just a bad guy all by himself.

Though people are usually joking around when they say "see you in hell," Armin pretty much means it when he says it to Eren in the anime ending of "Attack on Titan." This is different from the manga's ending, where it seems like Armin has separated himself from Eren's horrifying actions. The anime shows Armin being disgusted and angry with Eren, but also with himself.

Diplomacy and destruction

The anime ending of "Attack on Titan" is, like the manga ending, a real kick to the heart. However, the anime gives a glimmer of hope to the proceedings by playing into the emotional differences in Armin and Eren's approaches to peace.

Eren truly seems helpless to the idea that he must destroy life to create peace. Armin, though guilty of violence as well, longs to use diplomacy instead of destruction in his pursuit of a better, more unified world. In the ending of the anime, this is shown both by Armin's heartfelt insistence that Eren's doomed way isn't the only way — and, after Eren's death, when viewers see Armin actually engaging in diplomacy.

While the audience has seen some Marleyan characters humanized via the episode following the time skip, Armin goes so far as to engage in outreach with the Marleyans. A world is in the process of being rebuilt after Eren's antics, and Armin is ready to help create a coalition that crosses old boundaries. The train and letter scene shows the start of what could be a long career of communication for Armin, all in the attempt to put some of the ideas he pressed on doomed Eren into practice. Armin's efforts clearly help achieve peace for at least a little while.

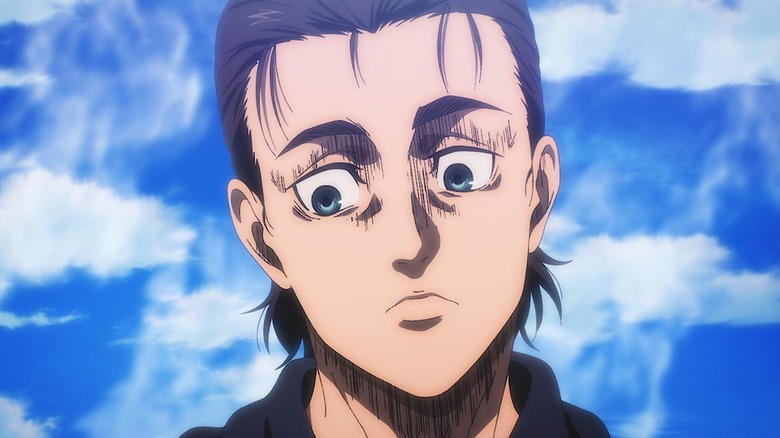

Eren's madness seems more pronounced in the anime

Eren's sanity slipping and time traveling takes a serious toll on him in the ending of both the anime and the manga of "Attack on Titan." Eren seems genuinely tortured by experiencing all timestreams at once, and seeing him in kid form with Armin and young adult form with Mikasa, contrasted with him in his end-times form with present-day Armin ... we kind of get where he's coming from.

The changing stakes of the Rumbling also seem to have had an effect on Eren. At one point, the Rumbling is said to save the future of all humanity by destroying a percentage of the world beyond the walls. Then, when Eren and his friends discover there's more of humanity left than Paradis, the Rumbling doesn't seem like the only solution.

Still, Eren feels it's his fated solution. His future memories make him convinced it is the only way, even when his friends (and those post-time-skip scenes) attempt to show him that the enemies they're fighting are just as human as they are. Eren is operating deep within the sunk cost fallacy of revenge, and his motivations are as tangled and confused as his own experience of time. While this is also true of the manga ending, it is potently disorienting in the anime.

Paradis lost

While the manga ending of "Attack on Titan" did show some of what becomes of Paradis after Eren loses his head and attempts to initiate the Rumbling, the anime expands on that future. Primarily, this is achieved through a static shot over the course of many, many years.

The mainstay of this shot, much like its corresponding panel in the manga, is the tree Eren always slept under. It is also the site of his final resting place, and where viewers watch Mikasa bury her slain love. Years, then decades pass. Grass grows and flowers bloom, and a cycle of peace begins. We watch Mikasa grow old, and return to the grave with her own family. Later, it appears she is laid to rest there as well, with flowers in her hands.

Beyond the tree, and even more years later, we see the cycle of peace and war shift into something sinister. A futuristic city is built up in Paradis, and all too soon it is being shot apart with weapons from above. While these panels are similar to the manga, the weight of time, change, and cycle are played out for longer — and to more bittersweet, heartbreaking effect.

The anime has a more clear theme

People being compelled to hate each other, even though they can love one another, is a major theme the manga and anime versions of "Attack on Titan" explore. However, the ending of the manga split fans, with many confused as to why a genocidal maniac was both celebrated by his friends and also unsuccessful in his "mission."

Some fans think the ending of the manga was subtle, and just didn't directly spell out the themes of the series. The anime version puts a finer point on the same themes of the manga, but also seems to be less ambiguous about Eren's so-called sacrifice. It's hard to think his affair with the dark side and attempt to engage the "Rumbling" was worth it — especially if war was bound to return to Paradis, in one form or another, one day.

The relentless cycle of near-endless war with brief peace haunts every aspect of "Attack on Titan." While the anime ending doesn't blatantly spell out that Eren died a supervillain for no reason, it still shows that Eren's complicated desire to cause the Rumbling doesn't actually solve anything — although the anime's ending is less thematically ambiguous than the manga. It also gives viewers a sense, depending on their interpretation, that a new, better hope might be possible with this next cycle — perhaps if a character like Eren actually listened to the counsel of his friends in his darkest moment, and didn't get ready to rumble, after all.

The medium impacts emotions differently

Reading and watching something are two entirely different experiences, with limitations and benefits to each. That's why it's hard to compare manga to anime. What's interesting about "Attack on Titan" is that, due to Imayasa being involved so intimately with both interpretations of his story, and the fact that the two versions are separated by several years, he and his team had the opportunity to adjust the epic ending for the screen.

According to an interview with The New York Times, Isayama always knew the ending he would give both the anime and manga, and even after the original iteration tanked with many fans, he felt compelled to keep it. He might have grown as a writer and storyteller enough to give more nuance, shade, and poignancy to his tragedy — but he also grew to struggle under the burden of his art.

Isayama told The New York Times, "I was tied down to what I had originally envisioned when I was young. And so, manga became a very restrictive art form for me, similar to how the massive powers that Eren acquired ended up restricting him." Much of the manga is accurately represented in the anime. However, perhaps just because of the shift in mediums, the anime is able to let the emotional beats of the story play out longer onscreen, as well as augment those moments with actors' living, breathing performances.