Every Coen Brothers Movie Ranked Worst To Best

Over the past 30-plus years, Joel and Ethan Coen (better known as the Coen Brothers) have become one of the most prominent filmmaking duos in the history of cinema. They've managed that feat by funneling a fearless, fiercely original energy into a near-unimpeachable slate of films comprised of quirky, intelligent, and artistically bold stories across every genre imaginable.

Whether they're trudging through the dusty trails of the Old West, the snow-covered landscapes of the Dakotas, or the hallowed backlots of Hollywood's Golden Age, the Coens always push themselves into unknown territory, and deliver uniquely off-kilter, feverishly idiosyncratic visions of worlds — whether past or present — not wholly dissimilar to our own. While it's all but impossible to find a genuine black mark among their work, Coen Bros. movies are not all created equal (would that it were so simple). With that in mind, here's our list of every Coen Bros. movie ranked worst to best.

18. The Ladykillers

Prior to 2004, Joel and Ethan Coen had spent two decades making a name for themselves by crafting a series of inventive, wildly original films unlike anything anyone else in the movie biz was making. Of course, at that point, all ten of their movies had been original concepts written and directed by the brothers themselves. That changed when they signed on to remake a campy Brit-crime flick from 1955 called The Ladykillers.

That's a decision they likely regretted. While their adaptation of The Ladykillers is often gorgeous to look at (thanks to their frequent director of photography, Roger Deakins), nothing much else works. The comedy falls flat. The moral quandaries are simplistic at best and pandering at worst. Tom Hanks' turn as a would-be Southern gentleman/scoundrel is as distracting as his absurdly over the top coif and dental prosthetic. There's really not much else to say about The Ladykillers except that it's a rare genuine misfire, that sometimes a lukewarm to terrible critical response is completely on point, and that the Coens are usually at their best when working with their own material.

17. Intolerable Cruelty

Now that we've got the Coens' one genuine misfire out of the way, let's spend a moment with its near-fabulous but ultimately middling predecessor, Intolerable Cruelty. For those who don't recall this occasionally riotous little crime picture, it stars George Clooney as a divorce lawyer and Catherine Zeta-Jones as a gold-digging dilettante about to dupe a billionaire oil baron. There was real hype around Intolerable Cruelty before its release, because it re-teamed the brothers with Clooney, and marked their first go at applying their skewed worldview to the screwball romantic comedy genre.

Sadly, they just missed the mark. While Intolerable Cruelty features one of George Clooney's all-time greatest line readings, the chemistry between Clooney and Zeta-Jones is palpable throughout, the film is bogged down by labored plotting, thinly-drawn side characters, and a third act that twists one too many times for comfort. Like an unsatisfying marriage, Intolerable Cruelty is — occasional outbursts of charm and hilarity aside — mostly dull and plodding, and it's a relief when it finally ends.

16. Hail, Caesar!

Throughout their career, the Coen Bros. have categorically refused to work within a singular cinematic genre. They've jumped and combined genres with such uncanny agility over the years that the words "the Coen Brothers" now intone a cinematic genre all its own; one born of outlandish characters, crackling dialogue, pitch black humor, and a non-Hollywood approach to style and story. An anthology film of sorts spread across the backlots of a film studio in the 1950s, Hail, Caesar! saw the Coens packing all those elements into a Hollywood fable about the studio system of old.

Told through the eyes of a "studio fixer," the movie dabbles in just about every film genre you can conjure — musical, western, period epic, crime, comedy, political drama, and even a decidedly complicated chamber piece — into one single film. While that approach gives the film's more than estimable cast ample room to deliver serious laughs, there's just a bit too much going on for any one storyline to resonate the way you'd expect with a Coen film. That ultimately leaves Hail, Caesar! dancing on the stronger side of the brothers' lighter works — which still makes it better than most movies that get released.

15. Burn After Reading

Most filmmakers never make a movie that can be considered a legitimate masterpiece, and the ones who do almost never immediately follow one masterpiece with another. Joel and Ethan Coen are not unlike most filmmakers in that regard — i.e. Barton Fink was followed by The Hudsucker Proxy, Inside Llewyn Davis was followed by Hail, Caesar, and No Country for Old Men was followed by Burn After Reading.

Not that The Coens' espionage-tinged caper comedy isn't an intriguing addition to their oeuvre. It very much is, and features a screenplay that somehow ranks among both the darkest and funniest they've ever written — not to mention stellar performances form the likes of George Clooney, Frances McDormand, John Malkovich, Tilda Swinton, and a marvelously over-the-top Brad Pitt. To be honest, if Burn After Reading had been released anywhere else in the Coens' filmography, it would likely rank higher on this list. Unfortunately, the film was released a year after their nihilist opus No Country for Old Men, and while it's occasionally brilliant (and well worth a revisit), it still comes across a bit shallow in the company of such lofty fare.

14. The Hudsucker Proxy

With its hard-to-love characters, its dialogue that verges on annoying, its absurdist plot, and a twist of the fantastical that never quite feels at home within the Coen-verse, The Hudsucker Proxy (co-scripted with their old pal Sam Raimi) is undoubtedly one of the most maligned and forgotten films in the brothers' filmography. That's a shame, because a closer look reveals well-drawn characters, brisk dialogue, and a giddily absurdist plot (about the invention of the hula hoop). In short, The Hudsucker Proxy might be the most misunderstood film the Coens have made to date.

We're not gonna hard sell you on the film though, mostly because we're sure if you've seen The Hudsucker Proxy, you've already forged some very specific opinions about it. If that's the case, we'd encourage you to give this impassioned, wholly original fantastical comedy another swing of the hips, because there's a lot more going on here than you think — in particular a boldly adventurous, endlessly fascinating performance from Jennifer Jason Leigh. If you've yet to see The Hudsucker Proxy, track down a copy immediately, and enjoy falling head over heels for this oddball classic.

13. True Grit

When the Coens first took a shot at a remake with The Ladykillers, they got more things wrong than right. Luckily, they learned from the experience, and when the duo set out to remake a bona fide Western classic, they managed to get just about everything right. The film in question is, of course, the Coens' 2010 remake of the John Wayne classic True Grit.

It took some serious chutzpah to tackle a film held in such high esteem by cineastes and novices alike. The Coens wisely didn't try to reinvent the wheel, allowing their True Grit narrative to unfold in pretty much the same fashion as the original, with a young woman hiring a fading gun-hand to help track down the man who killed her father.

It also helps that the brothers didn't use the original Duke vehicle as their primary source, opting instead to mine Charles Portis' novel as the inspiration. They then dressed the story up with their own narrative and stylistic flourishes, pulled brilliant performances from Jeff Bridges and Matt Damon (not to mention a show-stopping turn from then-newcomer Hailee Steinfeld) to deliver not just a great remake of a classic film, but one of the best remakes ever produced.

12. The Man Who Wasn't There

If The Hudsucker Proxy is the most misunderstood film in the Coens' body of work, it's only because The Man Who Wasn't There is a film all but beyond rational comprehension. That's not necessarily a bad thing. Part noirish thriller, part metaphysical mystery, and part scathing indictment of capitalist culture, TMWWT casts Billy Bob Thornton as a dispirited, sub-verbose barber who thinks his ship has come in when a charismatic stranger offers a chance to invest in a new fad called "dry cleaning."

From that unusual setup, the brothers spin one of the weirdest stories they've ever concocted, and deliver a wholly original neo-noir thriller fit for the modern age. The film is bolstered by Roger Deakins' stark black-and-white photography and a career best turn from Thornton (who smokes more than he talks here). That being said, the film's meticulous pacing and cast of patently unlikable characters make The Man Who Wasn't There a film that's almost impossible to love. But it's just as impossible to hate, and if you embrace The Man Who Wasn't There's eccentricities, you might find it's not quite as out there as it seems — at least until the spaceship shows up.

11. The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

If their staggering body of work has taught us anything, it's that the Coen Brothers have no shortage of original stories to tell, that they want to tell them all no matter how big or how small, and that they're always willing to push themselves into new territory. So it was that when the pair announced they were working on a Western anthology for Netflix, a whole new world seemed to open up. First and foremost, it was the first time the Coens had looked to a streaming service for one of their projects, and also because said project — titled The Ballad of Buster Scruggs — was thought to be their first crack at an original series.

That series turned out to be a single, sprawling, Western anthology film composed of six disparate tales of the west. Some are funny, others dramatic, and a couple are downright heartbreaking. In true Coen fashion, those elements are often at play within the same story (if not a single scene), making The Ballad of Buster Scruggs a giddy and galvanizing cinematic experience wholly unique to the Coens' work, even if it isn't quite coherent enough to rank among their very best.

10. Miller's Crossing

Though crime and criminals factor into nearly every Coen Brothers film, they've made just one legitimate gangster flick. In case you were wondering, Miller's Crossing is a near-flawless gangster epic, and it's the only one they'll ever need to make.

Set in a bustling, prohibition-era metropolis, Miller's Crossing follows the chief advisor (a cooler than cool Gabriel Byrne) of a mob kingpin (the inimitable Albert Finney) as they try to navigate the shifting tides of a particularly nasty turf war. Of those tides, we'll say that they never lead quite where you'd expect, that the stakes are nothing short of life and death for everyone involved, and that saying any more would spoil the fun of watching Miller's Crossing.

What we can say is that of the Coens' 29 produced writing credits, Miller's Crossing stands as some of their finest work, that their use of language throughout the film makes it as much fun to listen to as it is to watch, and that as great as Byrne, Finney, John Turturro, and Jon Polito are in Miller's Crossing, it's at its best when Marcia Gay Harden's Verna commands the screen.

9. The Big Lebowski

It's a harrowing mistaken identity crime thriller about an average dude trying to replace his rug. It's a campy comedy classic about a fish out of water who gets in way over his head in the seedy underground of the San Fernando Valley. It's a character study about an aging stoner whose ambition in life is to smoke grass, drink White Russians, listen to Creedence on repeat, and occasionally hit the bowling alley for league play. It's also one of the greatest cult films ever made, one of the most quotable scripts ever produced, and the cherry on top of a decade that saw Joel and Ethan Coen come into their own as filmmakers with trippy, insightful, endlessly re-watchable (and award-winning) works like Miller's Crossing, Barton Fink, and Fargo.

Look, there's really not much we can say about The Big Lebowski that hasn't been said already. You either abide The Big Lebowski as the masterfully envisioned madcap stoner epic masterpiece that it is or, well, you're just wrong. And yes, of the Coens' many meditative genre mashups and cinematic experiments, The Big Lebowski is the one that ties their entire filmography together.

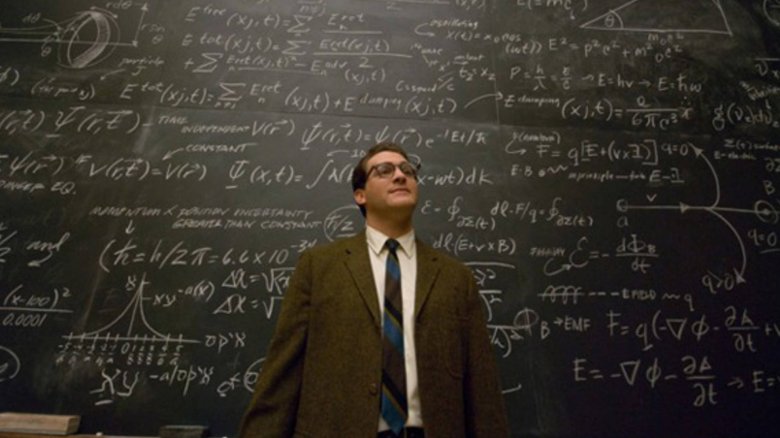

8. A Serious Man

Like crime and criminals, religion has often found its way into the Coens' films. With their caustic Judiastic farce A Serious Man, The brothers put faith front and center, and deliver a seriously complicated religious parable about a Jewish physics professor searching for meaning as his life falls apart around him.

Watching a man's entire life crumble hardly sounds like the formula for great comedy. And yes, there are scenes in A Serious Man almost too cringeworthy to sit through. But even in the film's heaviest moments, the Coens twist the dagger of levity just enough to keep it from becoming a blunt trauma sort of drama.

They're aided in that endeavor by a dexterous performance from Michael Stuhlbarg, who wades his character through the film's complex moral quandaries with the comedic timing of a Marx Brother and the patience of Job. A Serious Man may test your patience too, but if you grew up in the Jewish faith, the film — with its winking in-jokes and scores of Judaic details — will hit extremely close to home. Don't worry, the Goys will also find a few hearty laughs and pearls of wisdom in this oft-overlooked gem as well.

7. O Brother, Where Art Thou?

In 1941, Preston Sturges directed a largely unheralded film called Sullivan's Travels about a Hollywood director living as a hobo in hopes of understanding the plights of the poor. Problem is, he's using the experience as material for a depression-era drama he's titled O Brother, Where Art Thou?

While that film-within-a-film isn't really the inspiration for the Coens' 2000 film of the same name, one can't help but notice their O Brother, Where Art Thou? is a depression-era tale about penniless escaped convicts perilously traversing the American South in search of a fabled treasure. In reality, the Coens claim Homer's epic poem The Odyssey as the film's source material, though they also claim to have never read the poem itself.

That's okay, because the batty, beautiful, alterna-musical they crafted — featuring winning turns from George Clooney, John Turturro, and Tim Blake Nelson — is a timeless, hilarious southern fried epic in its own right. It finally brought the Coens' off-kilter sensibilities to the mainstream, and its bluegrassy soundtrack became a legit cultural phenomenon. Just FYI, O Brother, Where Art Thou? also remains a high mark creatively and commercially for the Brothers Coen.

6. Fargo

If O Brother, Where Art Thou? finally landed the Coen Bros. squarely in the mainstream, Fargo is the film that launched them in that direction. That's a bit surprising, as it's also one of the darkest films they've made. But if there's one thing certain about modern movie audiences, it's that the only thing they love more than a cheap laugh is a bleaker than bleak crime drama soaked in blood and served up with at least a hint of folksy Americana.

A tragic tale of a kidnapping scheme gone unimaginably wrong against the icy backdrops of North Dakota and Minnesota, Fargo features all of those things in spades. It also features a razor sharp, Oscar-winning screenplay and an Oscar-winning performance from Frances McDormand to boot — not to mention equally praise-worthy work from William H. Macy, Steve Buscemi, and Peter Stormare. While Fargo is one of the Coens' more serious cinematic ventures, it still features their signature dark humor, vibrant language, colorful characters, and of course, brutal outbursts of violence. It all comes together to make Fargo one of the most uniquely Coenesque movies ever made.

5. Raising Arizona

Savvy filmgoers had the Coens on their radar for almost a decade prior to Fargo's release, and Raising Arizona — their bonkers screwball masterpiece from 1987 — is what got them there. Set against the barren, dusty vistas of a desolate desert town, Raising Arizona tells the story of a career convict (Nicolas Cage in a giddily unhinged performance) and a police officer (an inspired Holly Hunter in a rather rare comedic role) who, in the face of fertility troubles, decide to lighten the load of furniture tycoon Nathan Arizona by kidnapping one of his newborn quintuplets.

Raising Arizona only gets crazier as that improbable narrative unfolds... which maybe raises a few questions. For instance, is Raising Arizona a comedy of errors about lovable kidnappers almost getting away with a heinous crime? Yes. Is it a Reagan-era parable about trickle-down economics and prison reform gone haywire? Depends on your own political beliefs. Is Raising Arizona a radically idealistic farce that heralded the arrival of a bold new cinematic vision? Yes. It's also crazy in all the best ways, and if you don't believe that, you simply cannot call yourself a Coen Bros. fan.

4. Barton Fink

Though many of the Coens' films are tied together by thematic elements and a fiercely loyal stable of collaborators, none of their films are directly connected narratively. There are, however, Coen Bros. films that feel a little more connected than others, and of those, none more directly influenced each other than 1990's Miller's Crossing and 1991's Palme d'Or-winning meta masterpiece Barton Fink.

What's the connection? As the story goes, while writing Miller's Crossing, the brothers hit a creative wall so fierce they put the project on hold. In hopes of kickstarting their creative juices, they conceptualized a new film centered around a character created specifically for John Turturro. And so, from the vast creative void that is writer's block, a wildly original, scathingly satirical, pseudo-mystical masterpiece was born — a masterpiece about, of all things, a writer facing a devastating creative block, not to mention a full-fledged metaphysical crisis of identity that may or may not directly involve the devil incarnate. Simply put, Barton Fink is a haunting look at the life of the creative mind the likes of which moviegoers had never seen before, and possibly even since.

3. Inside Llewyn Davis

One of the prevalent themes throughout the Coens' career has been their whole-hearted embrace of tragically fallible central characters — characters so beautifully flawed that viewers can invariably see part of themselves in each, no matter if they're the good guys, the bad guys, or some messy mixture of both.

Llewyn Davis is manipulative, self-centered, and maybe not as talented as he believes himself to be. He's also a charming, intelligent, intensely likable guy who sings and plays adequately and usually at least tries to do some semblance of the right thing. He is, in fact, the very definition of "messy mixture," and that's what makes Inside Llewyn Davis such a fascinating experiment in character.

It helps that said character is played with equal parts charm, swagger, and crippling insecurity by Oscar Isaac in a star-making turn. It also helps that Llewyn Davis is maybe the most skillfully-scripted protagonist the Coens have ever envisioned. Watching Isaac portray such an identifiable, beautifully flawed character is enough to make Inside Llewyn Davis worth a look. That the music, the settings, and the supporting characters are crafted with equal skill and care is what makes Inside Llewyn Davis one of the Coens' most memorable works to date.

2. Blood Simple

History has taught us that fledgling filmmakers are all but doomed to get everything wrong on their first movie. Joel and Ethan Coen didn't get the memo. While it's hard to believe that they made their feature debut over 30 years ago, it's harder still to believe just how much they got right with that debut film. What's truly mind-blowing is just how well Blood Simple holds up decades after its release.

Make no mistake, Blood Simple is still every bit the biting, brutal, exactingly scripted, and exquisitely photographed noir-soaked thriller it was upon its release. It still features an all-time best screen debut from a young Frances McDormand, who's matched every step of the way with maniacally sleazy work from Dan Hedaya and a villainous turn for the ages from an against-type M. Emmet Walsh. It also still boasts one of the great match-cuts in cinema history, and its menacing, white-knuckle finale will still leave your palms sweaty as it feverishly unfolds before your eyes. So yes, Blood Simple is one of the most staggeringly assured debut films ever produced, and it remains one of the Coen Brothers' best. Period.

1. No Country For Old Men

From top to bottom, their films are possessed of a certain literary quality, but prior to 2007's No Counter for Old Men, the closest the Coens had ever come to a proper literary adaptation was O Brother, Where Art Thou?'s extremely loose take on The Odyssey. As they did with their feature film debut, the brothers managed to get things right and then some with their first literary adaptation.

They chose an absolute beast of a book to adapt, as it happens. Written by legendary scribe Cormac McCarthy and possessed of stark Western themes, bracingly barren wit and a next-level sort of Gothic nihilism, No Country for Old Men seemed tailor made for The Coens' peculiar sensibilities, particularly a wild nihilistic bent that plays in one way or another through all of their films.

Sensibilities aside, the Coens took the bones of McCarthy's No Country for Old Men and ran with them, delivering a high-minded art film dressed up as one of the great crime/chase thrillers cinema has ever seen. Along they way, they pulled startlingly sparse performances from Tommy Lee Jones and Josh Brolin, and an iconically villainous (and Oscar-winning) turn from Javier Bardem. In short, No Country stands as the crowning achievement of Joel and Ethan Coen's career in film, not to mention a nihilist masterpiece to end them all. It also happened to net the Brothers their one and only Oscar for Best Director.