There's A Horror Sequel Trend That Needs To Die A Quick Death

Decades late to the game, Hollywood is finally seeing horror as the viable moneymaker it's always been. Granted, it's making up for lost time by simply rebooting, sequelizing, or requelizing films it should have paid attention to the first time around, but we'll take what we can get, especially since these installments have been (for the most part) pretty watchable.

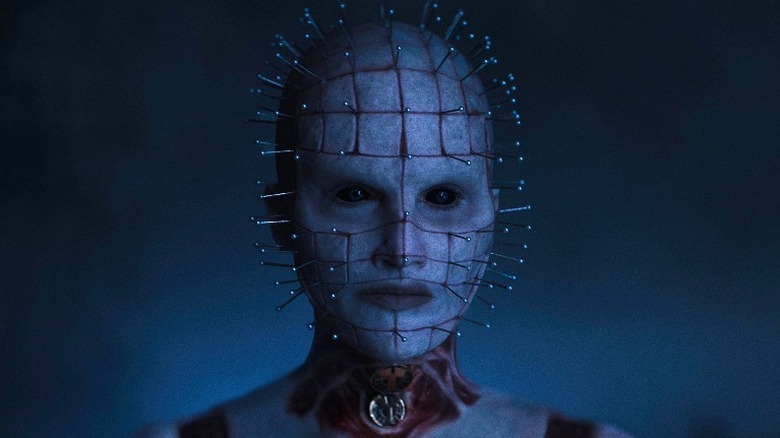

Unfortunately, this fad has come with the secondary trend of giving a reboot or follow-up the exact same title as the film its creatives insist it isn't remaking. The trend not only makes for confusing, cumbersome wording in horror articles (apologies in advance), but directly contradicts the marketing and supposed ethos of non-remakes. To wit: in a September 2022 interview with Entertainment Weekly, director David Bruckner said of his then-upcoming "Hellraiser" reboot: "This is not a remake. I just didn't think you could ever remake the original Hellraiser. It's too much its own thing [...]" Last October, while defending his new "Halloween" trilogy to Games Radar, director David Gordon Green said, "Some people just want to literally watch the original film. You're not going to remake that; you have to do something different." And in an interview with Drew Barrymore (via YouTube), Courtney Cox insisted that "Scream" (2022) was somehow both the fifth installment in the franchise, and a brand-new thing that was therefore "not 'Scream 5 [...] just a new 'Scream.'" Wait, what?

This "X isn't Y, it's just called Y" mantra may be an ultimately harmless sort of gaslighting, but when we break down the all-too-transparent marketing "whys" of this same-name-different-year title trend, its foolishness becomes as obvious as the "inject and spoon-feed commentary, rinse and repeat" formula at play in some of these new chapters.

That isn't This, and vice versa, should be a given

There's a reason James Joyce didn't call "Ulysses" his 1922 novel, "The Odyssey." For starters, it wasn't "The Odyssey," or even a translation or remake thereof, but rather, a modernist reimagining of Homer's epic. And if it had been a kind of sequel or reboot, it still would not be "The Odyssey," because — and here's where things get very obvious and irrefutable — "The Odyssey" is already "The Odyssey."

Similarly — and yes, we very much are comparing seminal horror films to Homer – "Halloween" is already "Halloween." "Scream" is already "Scream." "Hellraiser" is already "Hellraiser." And listen, David Gordon Green, for the love of all that is good and holy in this world, "The Exorcist" (and only "The Exorcist") is already "The Exorcist." Reboots, sequels, and prequels of "The Exorcist," of the sort that Green is currently working on (per Variety) are always welcome. But they are not ever going to be "The Exorcist" in the same sense, on an artistic or cultural level.

One shouldn't have to put "the original ____" in front of classic horror titles to communicate the precise films to which they refer, because their contemporary additions aren't remakes. Yes, "Scream" (2022) — see what we mean about how cumbersome this titling trend is? — tried to convince us that it was a different thing entirely. But since the vast majority of sequels released years after their most recent predecessor are already, by default, also reboots — aka "requels" — all it did was tie a shiny little portmanteau bow around a thing that, again, already existed.

Now that we've established that a film that is not another film shouldn't have the same title as the film it's not, let try to find some logic in all this.

The industry wants us to correlate, not count

It's apparent that, somewhere along the way, Hollywood decided that tacking digits onto sequels made them somehow less appealing (per NPR). What's less apparent is why they decided to drop the reference point (and subtitle) altogether. Have our attention spans grown so very short that we can't read beyond a colon or a dash? If that's the case, throwing the same name at us for an entirely different movie definitely seems like way too much for our wee little consumer brains to handle, so, clearly, this isn't about relaying information to the viewer. There is something this technique lets us know, though, albeit on a more subconscious level.

Nostalgia can be a double-edged sword when it comes to reboots and sequels, but despite "Scream" (2022)'s feigned and over-reiterated rejection of it, it's also their main weapon. Because the original film — and that film's distinct (read: older) social and cinematic context — must already exist in order for an "update" to feel like it's giving us something more immediately relevant and worthwhile, a continuous reminder of "what came before" is a pretty handy means of showing us a new installment's more impressive departures. In other words, relevance is relative, and it needs a basis of comparison. What better way to force the viewer to make that comparison than by giving your film the same name as its less contemporary inspiration?

This trick is particularly useful for films that don't, in the end, actually offer us anything all that "new and improved."

What's in a name? Implied worth

David Gordon Green's "Halloween" (2018), for instance, earned an abundance of praise for its #MeToo relevance and its ambitious (if not fully realized) attempt to explore PTSD. But as reviews in both The Verge and RogerEbert.com note, it's more bogged-down by that commentary than buoyed by it. John Carpenter's "Halloween" is, lest we forget, laden with feminist themes and subtext, but like all the best horror films, it never has to sacrifice story (or scares — a pretty necessary element of horror) for commentary. The two are one and the same, because that's what fear, by proxy, does: it forces us to empathize and relate.

Unfortunately, while "Halloween" (2018) was many things, scary simply wasn't one of them. By calling itself "Halloween," however, it was able to trigger our compare and contrast reflex, and subsequently trick plenty of viewers into thinking it had added to Carpenter's narrative, solely because it was less subtle about its intentions.

Similar things can be said about "Scream" (2022), a film so utterly pleased with itself that it appears to have bought into its own lie. The film offers no new insight or thesis, and is most definitely not a brand-new launch. How in the world could it be, since it includes — and so desperately needs and relies on — the original movie's characters and narrative? Like "Halloween" (2018), it's far more concerned with its dissertation than with being scary (or even entertaining), but calling itself "Scream" makes that dissertation feel more important or relevant than it actually is. One thing it does do well is proactively paint any future criticism it might receive as mere nonsense from The Toxic Fandom, which makes it exceptionally difficult to call out without falling prey to one of the film's "Yeah, but we knew you'd say that" traps. B

ravo, we guess? That still doesn't make you "Scream," "Scream" (2022).

The exception to the rule is Candyman

What's perhaps most frustrating about the trend is that films like "Hellraiser" (2022), "Scream" (2022), and "Halloween" (2018) absolutely could have employed a simple number or subtitle and been just as popular. Were that the case, we might not have seen their directors' names mentioned anywhere near as frequently — read: it's easier to say "Bruckner's 'Hellraiser,'" when comparing it to Clive Barker's, than it is to switch back and forth between using, and not using, a date — but are there actually horror fans out there who pass up the opportunity to see Jamie Lee Curtis reprise her role as Laurie Strode simply because it came with a Roman numeral attached? Of course not. Universal could have called it "Stabby Mask Pumpkin Party XI: The Strodening," and we'd still all have turned out in droves to see it.

There's only one recent reboot wherein calling the film by its original's name isn't a transparent, sloppy marketing strategy, but an important thematic one: 2021's "Candyman," directed by Nia DaCosta. Unlike its fellow reboots and sequels, "Candyman" doesn't simply rely or cash-in on a much earlier film's title — it reclaims it. Thus, rather than refer to the reboot as "Candyman" (2021), we should really refer to it as "Candyman," and leave the parenthetical dating for its dated predecessor, "Candyman" (1992).

In his review of the film, Roger Ebert reviewer Odie Henderson describes one particular scene as follows.

Candyman earns its title

Looking back on the film's trailer, Henderson writes, "That effective short highlighted one of the major themes [Nia] DaCosta and her co-writers Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld put into their script: the endless cycle of violence perpetrated on Black bodies by White supremacy and the system it created. This idea was baked into the 1992 version's tale of Daniel Robitaille (Tony Todd), the original Candyman, but the focus was primarily on the White protagonist's fate." Of the titular character and his meaning, Odie further writes, "Here's an entity whose immortality can only be realized by having his name (and by extension, the memory of his tragedy) spoken into existence."

It's relevant that when talking about the reboot, viewers — like the film's protagonists — must speak that name into existence. What's more, and unlike "Halloween" (2018), "Scream" (2022), and even "Hellraiser" (2022), "Candyman" is a film that can stand on its own. It doesn't need the original in the same way the others do, if at all. Bruckner's "Hellraiser" (See? There he is again!) doesn't connect directly to the original in the same way the other two do, but without the original, there's a whole lot about its narrative that we simply wouldn't know what to do with.

Unfortunately, the sheer ubiquity of this trend means "Candyman" is often lumped in with same-name reboots and sequels that are arbitrary and unnecessary, at best, and arrogant and overreaching at worst.

1, 2, 3, 4, 1 ... but now, 6? That's where we draw the line!

In 2023, we're on the cusp of yet another reboot installment situation. Because even though there was allegedly "not" a "Scream 5," the newest installment actually insists that we call it "Scream 6." All sense has officially gone out the window.

With this in mind, the industry would do well to consider one final point: horror fans aren't naive. We know better than to go up that staircase. We'd never ignore the gas station attendant's ominous warning. And you can't just call something new by the same title, insist that it's somehow simultaneously that thing and a new thing, and expect us to believe in something that so directly and ridiculously defies logic.

Look, we're thrilled that major studios are finally cozying up, however awkwardly, to horror. And we realize we can't expect Grandma to navigate the treacherous ins and outs of emoji use two weeks into getting her first smart phone. But Hollywood, you've gotta stop peeing on our leg and telling us it's "Halloween." It's not "Halloween." It will never be "Halloween." It literally can't be "Halloween," because — again, since we cannot stress this enough — "Halloween" is already "Halloween."

All Green's first installment can ever possibly be, particularly when spoken aloud instead of typed, is "Halloween Twenty Eighteen," and since the instant associations of such a title are already growing foggy less than a half-decade later, we can't imagine those numbers work better for the industry than a descriptive subtitle, or the good 'ol fashioned sequential numbers it apparently thinks it's above using. This much we know: these titles are certainly not working for us horror fans, or for anyone who knows how to count, read, watch a movie, or accept reality.