Small Details You Missed In Enola Holmes 2

One of our favorite Holmeses is back! As everyone knows, there is no shortage of reimagined tales of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's famous consulting detective, but in 2020, Netflix gained success with a new member of the Holmes clan: young Miss Enola, little sister to Mycroft (Sam Claflin) and Sherlock (Henry Cavill). Based on the books by Nancy Springer, Enola Holmes is a precocious sleuth in her own right, using her wit and moxie to get her through even the most precarious dilemma, be it caused by a cutthroat on her tail, or simply her own shortcomings in the finer points of conventional society etiquette. When we last saw her, Enola (Millie Bobby Brown) had thwarted a killer and their plot to keep voting rights out of the hands of those silly women, and now she's back with an all-new mystery to solve and more women to empower. In "Enola Holmes 2," the action is fast-paced and the stakes are higher than ever, so fans caught up in the whirlwind of this charming sequel might miss some details upon their first viewing. We're going to take a look at some, but be warned: SPOILERS ABOUND!

The important parts are true.

"Enola Holmes 2" opens with a title card: "Some of what follows is true. The important parts at least." This cheeky introduction, which appears on screen for no more than four seconds, is easily dismissed as a fun, lighthearted way to maybe make the film seem weightier than it is. If it's even noticed at all. Since "Fargo" in 1996 boldly lied, "This is a true story," — a meta joke the Coen brothers threw in to amuse themselves — no one has been able to take that statement from a feature film without the recommended daily allowance of sodium (via Decider). So it would be completely understandable if people overlooked this small detail until the end of the film, when a photo of the real Sarah Chapman is displayed, accompanied by the information that she led the first worker's strike by women for women, and improved working conditions for all. That shocking realization that "Hey, the important parts WERE true," inspires the viewer to want to start watching it again from the beginning. Brilliant strategy, really.

The Little Match Girls

When little Bessie Chapman (Serrana Su-Ling Bliss) tells Enola, "We're Match Girls, ain't we," it may have perked the ears of a few history buffs, but most people — particularly Americans — probably never learned about the London Match Girls Strike of the late 19th century. As in the film, the phosphorous handled by the (mostly female) workforce of the match factories was unsafe, infecting, and in many cases, killing those who habitually inhaled the dust and vapors given off by the chemical. Also factually represented in the film is the look of someone infected with this phosphorous poisoning. Although the movie reveals the company villains are intentionally mislabeling the epidemic killing their workers as a typhus outbreak, it doesn't actually tell what the true disease was. It shows, however.

As Enola goes "undercover" in the match factory, walking into work with Bessie, a young woman in front of her is barred from entering because of what the foreman sees in her mouth. As she turns to look at Enola, we see her jaw is extremely swollen, her face disfigured slightly as a result. This is an actual real-world prognosis of the effects of working with the white phosphorus – an affliction called "Phossy Jaw" for the way it attacks and deteriorates the jaw bone, causing pain, abscesses, inflammation, necrosis, and eventually fatal brain damage (via All That's Interesting). Interestingly, typhus, which is spread by biting insects in close, filthy quarters, manifests itself most often as a rash, a fever, and severe pain in the muscles and joints (via WebMD). So there were even more loose threads than Enola realized, just waiting to be pulled.

Additionally, "The Little Match Girl" is a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, the moral of which is to be charitable and take care of those less fortunate than you (via Lit Bug). From Enola to Tewkesbury (Louis Partridge) to the very philosophies of Sarah Chapman (Hannah Dodd) and Eudoria Holmes (Helena Bonham Carter), "The Little Match Girl's" theme is very much in line with that of "Enola Holmes 2."

There's no such thing as unskilled labor.

In the factory, Bessie installs Enola in the station next to her and quickly demonstrates the procedure for getting the matchsticks into the boxes. Her movements are practiced and smooth as the dozens of tiny sticks seamlessly transition from the long straight line of the comb into the 15-centimeter package with which we're all familiar. Just as she says to Enola, it looks plenty easy when she does it. Enola, who is sometimes socially clumsy but overall a highly capable young woman in almost every respect, lays the matches along the comb and already we can see things aren't right. It's not as smooth and straight a line as Bessie's, so naturally, when Enola goes to gather them up to their box, her hand movement snags, she pulls too hard in the wrong direction, and everything goes flying.

This will cost her a penny out of her eventual pay, the foreman promises. This small interaction conveys so much information: that the working conditions are unreasonable, that these workers are under the thumb of their employers, that they're in constant fear of stepping out of line or making even a tiny mistake because they can't afford to lose a cent of their income, and that there's no such thing as unskilled labor — it's a myth used to pay people low wages, to insist that they are expendable. But it no doubt took these ladies months, if not years, to become so proficient at what they do.

Don't be fooled by the tediousness of the task. Yes, businesses could get rid of one worker and replace her with someone else off the street, and maybe the new worker would eventually grow to be as good as or better than the one they let go, but it would be months and months of lower production and lost product before they would find out, which is why they traditionally tried to pass those costs off to the labor force. As Sarah and Enola helped the workers see, though, (and as Holmes matriarch Eudoria tries to instill in her daughter) many voices joined as one can make quite a lot of noise.

Red-tipped matchsticks

When Enola is searching the owner's office in the factory, she comes across a box of matches with red tips instead of the white tips they're boxing downstairs. Since Mr. Lyon (David Westhead) reveals it's been two years that "typhus" has been killing his match girls –- coincidentally over the same two years Mr. McIntyre (Tim McMullan) praised the factory for the increased profits garnered from going from red matches to white — it's extremely unlikely, and therefore highly suspicious, that Mr. Lyon would still be using the older, red-tipped version. Matches were a daily necessity in the 19th century, for light, for heat, for smoking, and for cooking, and thus in very high demand (via Medium). A tiny box of 30-50 matches would hardly last more than a couple of weeks at the outset. Mr. Lyon must have kept a cache of safer matches somewhere for his personal use.

In addition, Mr. McIntyre walks the factory floor covering his nose and mouth with his handkerchief, intent not to breathe the deadly vapors. This indicates that both men knew the fatal effects of the white-tipped matches, and also provides additional context for the boardroom conversation Enola hears only snatches of. Mr. Lyon and Mr. McIntyre are discussing being bled dry, and only after the facts of the case come to light, is it clear that the conversation was about how they were being blackmailed about their role in those girls' deaths.

The Game has feet

Even the most casual fan of the stories of Sherlock Holmes knows the phrase "The game is afoot," so it's a nice inclusion here when, upon realizing she's accepted her first (or second) real case, Enola says those same words in her narration of events. Later, after a setback of some seemingly bad poetry and nowhere else to turn, Enola has a bit of a breakthrough and excitedly exclaims, "The game has found its feet again." It's a lovely little moment that connects her to her brother, yet firmly establishes her own quirky, youthful personality and the joy she experiences in her sleuthing. Sherlock is rather staid and matter-of-fact in drawing his conclusions, a trait that vexes Enola from time to time (especially if he deduces something quicker than she did), but Enola is her own person. Flashbacks to her mother's instructions frequently remind us that Enola was always encouraged to follow her own path in life, but it's small, subtle characterizations like this that show she has.

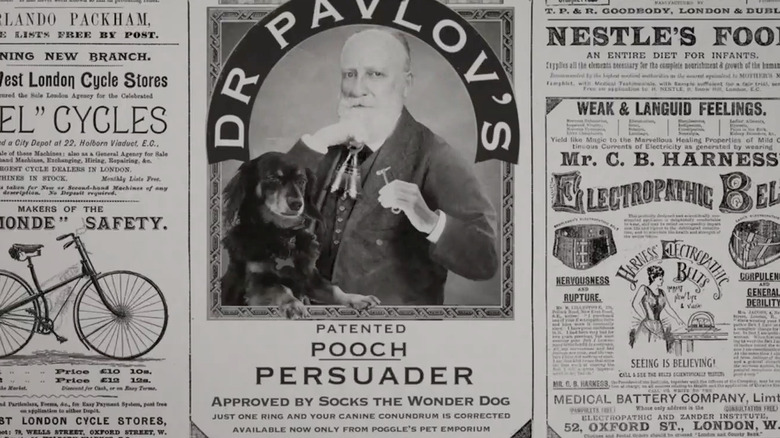

Dr. Pavlov's Pooch Persuader

When describing the feeling of being a detective and finally sussing out an answer to a mystery, Enola compares it first to a dressmaker finishing a skirt. She's actually never done that, though, so she reverses course and instead compares it to training a dog to sit.

Over this narration, the audience is presented with a small animation of what's meant to be a Victorian-era advertisement. Eagle-eyed observers will note this ad is for "Dr. Pavlov's Patented Pooch Persuader, approved by Socks, the Wonder Dog. Just one ring and your canine conundrum is corrected. Available now only from Poggle's Pet Emporium."

Right around the same time as the Match Girl Strike, Dr. Ivan Pavlov was performing his first experiments on conditional responses in dogs — those learned reactions in animals now coined Pavlovian Responses after the famous doctor. It's a fun little nod to the time period, and in the end credits, the ad has been updated, just as the experiments evolved and expanded over time. Dr. Pavlov's Patented Pooch Persuader is "now with two bells."

The history of Superintendent Grail?

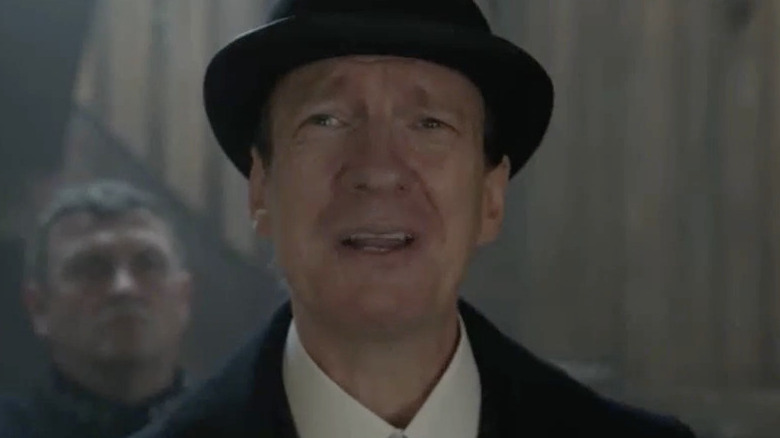

Even without the tell-tale sound of the steel tip of his cane, heard following Enola down a dark street just a couple scenes earlier, Superintendent Grail is an obvious danger to our heroine the first time we see his face. He emerges into the secret lodgings of Sarah Chapman with a menacing glower that only gets more intimidating the longer the scene goes, as circumstances look worse and worse for Enola and the dying woman she found. Luckily Enola escapes his clutches for the moment and flees to Sherlock's flat on Baker Street, but when she mentions Grail's presence to him he says, grimacing, that they have a history.

Events of "Enola Holmes" and "Enola Holmes 2" take place before the Conan Doyle tales, as evidenced by the fact that Sherlock has not yet met his trusty companion and chronicler Dr. Watson, so whatever "history" Sherlock has with Grail is not canon and has not come up in the "Enola Holmes" films. There is, however, a history with the actor.

Superintendent Grail is played by none other than David Thewlis, Professor Remus Lupin of the "Harry Potter" franchise, and Ares of "Wonder Woman" and "Zack Snyder's Justice League." Naturally, Henry Cavill's Superman was also in "Justice League," and while the two didn't have any connection in the film, it's still a fun bit of trivia. In the "Harry Potter" films, however, Lupin goes up against Helena Bonham Carter's Bellatrix Lestrange quite a few times. While she seems to get the better of him once again in "Enola Holmes 2," at least this time it's she who's in the right and he who is the villain.

Clothes switching

In the first "Enola Holmes" film, the young detective twice offers five pounds to a nearby boy to switch clothes with her. Allowing for the fact that the boy in question doesn't actually have to put on her dress, she is essentially asking for the opportunity to disguise herself in their garb. The exchange is never captured on screen, but Enola is next seen in both cases wearing the boy's clothes, so obviously, her plan worked well enough. It would be predictable and somewhat tired to insert this same scheme, with this same structure, into the sequel, which is why what they actually did is so great.

Enola has shown up in Sherlock's flat, dressed as a boy, hiding from the police. With exasperation, he sighs, "Dare I ask?" She breaks the fourth wall to give the camera a knowing grin, then the action cuts back to the previous scene. Enola is running from policemen wielding billy clubs. She finds herself, naturally, hanging from a roof in a perilous position as the rain gutter is about to detach and crash itself and Enola both to the ground. Through the window, however, there is a boy eating a bowl of soup. She asks him for a favor. Another hard cut and we see, not Enola back in her boy clothes, but the boy, in a tracking shot up his body, admiring his new dress and all the possibilities swimming behind his eyes. Is "Drag Race: Victorian British Empire" a thing? Somebody call RuPaul.

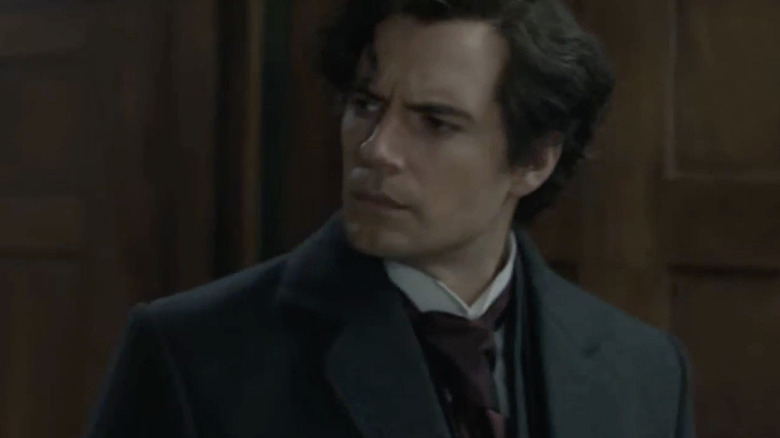

You have very recognizable shoulders

Despite some more recent entries into the compendium of the character, Sherlock Holmes was never meant to be a particularly sexy man. He's quiet, pensive, hyperlogical, socially awkward, misanthropic, and almost relentlessly single-minded when working a case. He isn't funny or charming or even amusing, really, unless you enjoy being told why the scuff marks on the fronts of your shoes indicate you're moonlighting as a cat burglar but not a very good one. As written, Sherlock Holmes is a bit of a dud. Brilliant, sure, but he's not going to make you laugh, much less swoon.

Suffice to say, however, that Henry Cavill is considered to be a bit of a dish. There are numerous pictures, memes, TikToks, and Instagram stories devoted to thirst trap photos of his physique, big sculpted shoulders included. So when Sherlock breaks into the tea rooms late at night and Edith (Susan Wokoma) says the only reason she didn't break his legs was that she recognized his shoulders? She is speaking for all of us in that moment.

Your mother sounds very different to mine

In "Enola Holmes," Tewkesbury is about to get his hair cut off with a knife by Enola, who is sharpening it on a stone. He asks where she learned to do that and she tells him it was her mother. He says, "Your mother is very different to mine." It's a touching moment when the two seem to bridge the gap of their differences a little, respecting and admiring them and maybe being a little envious of the life the other led. The exchange is a building block in the foundation of their relationship, carefully laid out in the film so that by the end, and into the sequel, their feelings for each other have been earned.

In "Enola Holmes 2," themes of independence and finding one's own way have been overtaken by themes of community and forming bonds with others, so when Sherlock comes to Edith for help — a desperate move such an isolationist would never have contemplated before — it's indicative of his own growth as a character, and his own willingness to form alliances and networks of aides, just as his sister is doing. Edith agrees to help him, saying, "Like my mother always said, 'Those who can turn to others when they're in need are the truly brave amongst us.'" Sherlock, who was raised by the same Eudoria Holmes that insisted Enola be self-sufficient, responds, "Your mother sounds very different to mine." Using this parallel phrase to the one in the first film again underscores the similarities between the siblings, and indicates the first few bricks laid in the foundation of Sherlock's own journey towards relationships of camaraderie, trust, and assistance.

Moriarty is an anagram

When Mira Troy (Sharon Duncan-Brewster) is revealed as the mastermind behind the blackmail and the devilish fiend that's been toying with Sherlock on a "merry dance" around the city, Sherlock outs her as her alias, Moriarty, and the film helpfully animates the letters he decoded earlier, unscrambling to spell out her name. However, the indication that Moriarty is an anagram is in plain sight long before this.

When Enola is at the ball, and Sherlock is at the same time deciphering the dance steps of his chase around the city, he puts a letter at each location on his map. When each location has been labeled, the letters spring to life and move around to spell out "Good to meet you, Sherlock Holmes." The camera then zooms in on the final note, the one indicating the single account where all of the missing money is being redirected, and each number of the account is assigned its correct letter. The result is "MORIARTY." However, if all of the other letters had to be unscrambled to come up with Sherlock's greeting message, it simply follows that this answer would be an anagram as well. Just before the midway point in the film, viewers with the sharpest skills will have their answer.

Additionally, Moriarty is an iconic villain, but the move to reveal Moriarty as a woman is always a little more cutting, a little bolder, than to keep him a man. The reason for this is exactly the reasons laid out by Mira Troy in "Enola Holmes 2." Women have no power, no station, no advantage. Even if they have minds sharper than everyone else (at this declaration, Enola and Sherlock hilariously give each other matching incredulous looks), they are relegated to the background, to the role of the subservient. It's not quite as stunning or as impressive a Moriarty reveal as that of the TV show "Elementary," which may never be bested, but the way Duncan-Brewster makes a meal out of her big scene, and especially the way she chews on that word "fun," is positively thrilling to watch. She's a Moriarty you could see people getting behind, even believing in. She's a Moriarty that might actually be a worthy rival.

The inevitable arrival of Dr. John Watson

Dr. Watson showing up at Sherlock's door at 4:00 p.m. on Thursday instead of Enola (10 seconds after "Enola Holmes 2's" end credits start, so don't be too quick to exit the stream) isn't that much of a surprise, truth be told, but it is a delight. Any allusion or connection of these stories to the canonical ones boosts their relationship in our minds. The "Enola Holmes" films seem more "true" to the original work, and therefore more legitimate on their own perhaps. What is surprising about Watson's arrival, however, is that Enola's been setting it up since her very first visit to Baker Street.

After running into a drunk and disorderly Sherlock outside of a London pub, Enola drags him back to his lodgings and witnesses firsthand the state of disorder in the rooms. Before leaving the next morning, she suggests the possibility of a flatmate, to help prevent any further descent into this cluttered and unkempt existence. The assumption, of course, is that she means herself. By the end of the film, when this time Sherlock is suggesting a meeting of the minds, Enola offers instead the olive branch of friendship and arranges a meeting with him that Thursday at 4:00 p.m. The assumption, again, is that she will be Sherlock's friend, but if you watch closely you notice that she simply offers up a time to him and he agrees, like she's had this planned. Enola didn't plan to meet with Sherlock on Thursday, happen to meet Dr. Watson in the interim, and set him up to be Sherlock's flatmate. Instead, she must've met him sometime earlier, arranged for Watson to be at Baker Street at 4:00 on a Thursday, and then made sure Sherlock would be there at the same time. She's a clever girl, his sister, and Sherlock's amused smirk at Watson's insistence that he had his information from "the young lady" correct, lets us know how fond he is of her cleverness.

End credits Easter eggs

As the end credits begin, they are designed to look like newspaper pages being turned. Then, there is a short scene that takes place at 4:00 p.m. on Thursday. Following that short interlude, the credits resume and are displayed on illustrated title cards designed in the style and manner of Victorian-era advertisement clippings, a cute nod to the era and to the aesthetic of the film. We see an image of the Paragon stage, and then Dr. Pavlov shows up again. After that, though, as the title cards switch from one set of crew members to the next, the illustrations become somewhat more personal.

Jack Thorne, who is credited as one of the people behind the story, is depicted as a boxer nicknamed "The Nib," another word for the tip of a pen. Nancy Springer, upon whose novels these films are based, appears next, in an ad for "Springer's Silver Fountain Pens, fine writing implements for the scholar and scribe." Producers are depicted as perfumers, milliners, confectioners, barristers, naval outfitters, bookbinders, florists, and, for some reason, sardine magnates. That's a thing, right?

Obviously, this was one last bit of fun for the filmmakers to include in a movie that's filled with tiny details audience members will only pick up after multiple rewatches. In fact, we'd better fire it up again to see what we missed.

"Enola Holmes 2" is streaming now on Netflix.