Angela Lansbury's 12 Best Films Ranked

The entertainment world lost a titan on Oct. 11, 2022, when actress Angela Lansbury died at age 96 (via Variety). Born in London in 1925, Lansbury moved to the United States as a teen, where she studied acting while working as a singer and cabaret performer. Her very first film role, in the 1944 thriller "Gaslight," earned her an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress, the first of three Oscar nominations she would receive. That alone would have made Lansbury's career one for the history books, but she remained a star of stage and screen for nearly eight decades. She won six Tony awards, including a lifetime achievement award in 2022 (via People), and helped transform musical theatre through her collaboration with Stephen Sondheim on works like "Gypsy" and "A Little Night Music." On television, she was best known as full-time novelist and part-time detective (or perhaps the other way around) Jessica Fletcher on the long-running CBS series "Murder, She Wrote," for which she received 12 consecutive Emmy nominations.

Lansbury was one of very few entertainers to be beloved not just across different media, but across generations. Children who loved her in 1944's "National Velvet" may have had children of their own who knew her best from 1971's "Bedknobs and Broomsticks," and then perhaps grandchildren who recognized her as Mrs. Potts from "Beauty and the Beast." A consummate professional, she kept working to the very end; her final film credit is Rian Johnson's "Knives Out" sequel "Glass Onion," a clear descendent of "Murder, She Wrote" and other star-studded whodunits. In honor of her passing, let's take a look at the 12 best films of Angela Lansbury, ranked.

Bedknobs and Broomsticks

The 1971 Disney film "Bedknobs and Broomsticks" takes place in 1940, as a trio of London war orphans is put into the reluctant care of a mail-order witch. Eglantine Price (Lansbury) is studying witchcraft via correspondence classes to use her magic to help fight the Germans, but when the school shuts down before she gets her final lesson, she and her new wards travel back to London to investigate. It turns out that the school's "headmaster" is nothing more than a charlatan (David Tomlinson) who had no idea that the spells he was selling — pulled from an old book of magic — were real. Together, they travel to a wondrous island full of animated animals to find the final spell and thwart a German platoon bent on invading Britain.

If the film feels a bit like "Mary Poppins" with a dash of "The Sound of Music" thrown in, well, you're not wrong. Based on a pair of novels by Mary Norton, production on the film originally began in the early 1960s when negotiations for the rights to "Mary Poppins" stalled out, utilizing much of the same creative team, including composers Richard and Robert Sherman, that would eventually work on "Mary Poppins" (per a 2009 interview with Richard Sherman). Reviews at the time compared the film unfavorably to that Julie Andrews classic, but it has a manic spirit all its own, and Lansbury brings a prickly charm to her witch-in-training. If anything from Disney can be considered a cult classic, this would be it.

Till the Clouds Roll By

A star-studded revue disguised as a biopic, MGM's 1946 production "Till the Clouds Roll By" is ostensibly the true story of Broadway composer Jerome Kern, but its real purpose is to stuff as many musical numbers performed by the biggest stars of its day as it can into a two-hour runtime. Lena Horne sings "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man" from "Show Boat" and "Why was I Born?" from "Sweet Adeline," while Judy Garland has three musical numbers (directed by husband Vincente Minnelli apart from the rest of the production) all to herself. Dinah Shore and Cyd Charisse both drop in for a song or two, and Frank Sinatra provides the film's climactic performance of "Ol' Man River."

Lansbury has just one number early in the film, as Kern (Robert Walker) is working to make a name for himself as a songwriter in London. A visit to the carnival provides the inspiration for "How'd You Like to Spoon with Me?" The song is a 1905 novelty tune that Lansbury performs as part of a musical revue, entering the stage from atop a giant swing and flanked by male chorus dancers. It's a small bit, but one that shows that Lansbury — just 21 at the time — was an immediate star.

The World of Henry Orient

The New York City of continental concert pianist Henry Orient (Peter Sellers) is one of glamor, sophistication, music, and extramarital affairs. It's in many ways a young person's fantasy of adult life, which is why upscale Manhattan latchkey kids Val (Tippy Walker) and Gil (Merrie Spaeth) become obsessed with him, ignoring the troubles in their own life by interfering with Henry's from afar. But when Val's neglectful mother Isabel (Lansbury) discovers that her daughter has been spying on a grown man, she confronts Henry — only for the two of them to embark on an affair of their own.

Director George Roy Hill's 1964 film was billed as a madcap Peter Sellers comedy; "meet two junior-size misses and one king-size nut!" the poster screams. But Hill brings a strong sense of autumnal melancholy to this tale of two girls growing up too fast, who can see the world of adults but can't quite grasp what it means. Lansbury shines as a woman with the opposite problem as her daughter, who got older but never grew up. Making a splash in her first scene with a low-cut shiny party dress, the role of a sexy, promiscuous older woman feels like a departure for her, but that may be because of our longstanding image of her as the matronly Jessica Fletcher. "The World of Henry Orient" is a reminder of Lansbury's range as an actor, and of the fact that she wasn't born a grandmother.

The Company of Wolves

But when Lansbury was a grandmother, she excelled at the task. Take Neil Jordan's 1984 fantasy film "The Company of Wolves," based on the writings of novelist Angela Carter (who co-wrote the screenplay). The young teenage girl Rosaleen (Sarah Patterson) visits a house out in the country and has a restless night full of dreams in which she is a fairy tale character living in a faraway time with her grandmother (Lansbury). Granny tells her frightening stories of wolves with "fur on the inside," intended to keep her wary of danger, but when an actual werewolf (Micha Bergese) comes calling, Rosaleen discovers that the old stories haven't prepared her for the seductive reality.

There's a lot going on in the film; like Carter's fiction, it plumbs the subconscious depths of tales like "Little Red Riding Hood" and the way they give voice to deep-seated fears of female sexuality and the threat of male violence. In this context, Granny is not just a wise storyteller, but a woman who has lived in the company of wolves herself and lived to tell about it. Rosaleen's dreamscape is a mishmash of different bygone eras; Jordan punctuates its lowkey dread with some truly gruesome transformation scenes, as when longtime Jordan muse Stephen Rea rips his skin off to reveal a sinewy wolf skeleton underneath.

The Harvey Girls

In the 1880s, businessman Fred Harvey began to staff his popular "Harvey House" railway stop restaurants and hotels with women, placing ads in newspapers across the Northeast and Midwest for educated women between the ages of 18 and 30 with high moral character. Hundreds of women answered the call over the years, drawn westward by a spirit of adventure and the promise of a generous salary ($18.50 a month, plus room and board). The so-called "Harvey Girls" became synonymous with the restaurant chain, and in 1946 were immortalized by George Sidney's nostalgic Western musical "The Harvey Girls," in which a jilted mail-order bride (Judy Garland) falls in with a group of young women traveling to open up their own Harvey House on the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe line.

The women's plan to open a new restaurant in town, one that provides clean, friendly service to all patrons, puts them at odds with the local saloon, a rough joint where showgirls dance the can-can every night. The leader of the showgirls, Em (Lansbury), quickly sniffs out that Susan (Garland) is not just a professional rival but a romantic one too, as they both have eyes for saloon owner Ned Trent (John Hodiak). As in "The World of Henry Orient" nearly two decades later, Lansbury clearly relishes the chance to vamp it up as a "bad girl" and gets a couple of fun songs courtesy of Johnny Mercer, although her singing voice was dubbed over by singer Virginia Rees.

Gaslight

The term "gaslighting" has become so widely used in recent years that many people don't even realize that it is in reference to a stage play turned movie thriller — and still others will cleverly try to convince people that there was no such film. Based on a 1938 play by Patrick Hamilton and previously adapted for film in 1940, 1944's "Gaslight" stars Ingrid Bergman as Victorian-era opera singer Paula, who moves back into her deceased aunt's London home with her dashing new husband Gregory (Charles Boyer). Soon, however, she begins to experience strange goings-on: items going missing, the sound of footsteps coming from the sealed-off attic space, and the occasional dimming of the gaslight lamps as if the lights were being turned on elsewhere in the house. Gregory insists that this is all in her head; could Paula be losing her mind, as her mother did, or is there something more sinister going on?

Of course, the modern usage of the film's title gives away the answer: Paula is being manipulated for nefarious purposes by Gregory, which isn't even the man's real name. Lansbury co-stars as Nancy, Paula's new housemaid who, while perhaps not fully in on Gregory's scheme, seems more than willing to lean into the idea that Paula is mentally unstable. According to a Variety story from 1943, a 17-year-old Lansbury was spotted at a party by the film's co-screenwriter John Van Druten, who encouraged her to screen test for director George Cukor. It was her first film role and would earn her first Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress.

The Long, Hot Summer

William Faulkner's Mississippi comes to vibrant, sweltering life in Martin Ritt's 1958 drama "The Long, Hot Summer." Adapted from three unrelated short stories, the film stretches across the eponymous season as handsome drifter and accused barn burner Ben Quick (Paul Newman) gets entangled with the wealthy Varner family: Overbearing patriarch Will (Orson Welles), insecure son Jody (Anthony Franciosa), and beautiful but standoffish daughter Clara (Joanne Woodward). Ben's entrance into their lives throws the entire family into chaos; secrets and recriminations bubble to the surface, and long-buried passions roar back to life. Will sees himself in Ben, and before long he has invited the young man to live in their house and work at the family store in town, spurring jealousy and rage in Jody. Clara, meanwhile, wants little to do with Ben, but finds her cold fish fiance (Richard Anderson) looking worse and worse by comparison.

Lansbury plays Minnie Littlejohn, owner of the local boarding house and Will's longtime mistress who dreams of having dinner with him at a reasonable hour, rather than having him sneak in her back door after dark. Her role is surprisingly small, living on the sidelines of a film that primarily serves to showcase Newman and Woodward at the height of their beauty and charisma. But she and Welles, both playing older than they are and both in a fallow moment in their careers, have a great lived-in feel for their characters and one another, even selling the film's tacked-on happy ending.

The Picture of Dorian Gray

1945's "The Picture of Dorian Gray" was Lansbury's third film appearance and resulted in her second Oscar nomination. As music hall singer Sybil Vane, she quickly falls in love with handsome young aristocrat Dorian Gray (Hurd Hatfield) thanks to a soulful conversation about youth, aging, and a Chopin prelude. But when Dorian coldly breaks off their engagement in pursuit of pleasure above all else, a devastated Sybil takes her own life. Little did she know of Dorian's dark secret, the magic wish he had made to keep his body young and handsome, while a portrait in his attic grows decrepit and deformed, not just by the passing years, but by the evil deeds Dorian commits. Rather than change his ways after the death of Sybil, Dorian sees that the magic works and that he can live without responsibility or consequence, growing ever more debauched.

Based on the novel by Oscar Wilde and directed by Albert Lewin, the film also stars George Sanders as a hedonistic nobleman who encourages Dorian's worst impulses, and Donna Reed as Dorian's fiancee, who nearly suffers the same fate as Sybil did many years before. As Dorian, Hatfield might as well have been a portrait himself; his pale face and eerily still performance make him feel like a movie monster and make Lansbury all the more vibrant and alive by comparison. Years later, she would reprise her song from the film, "Goodbye Little Yellow Bird," on an episode of "Murder, She Wrote."

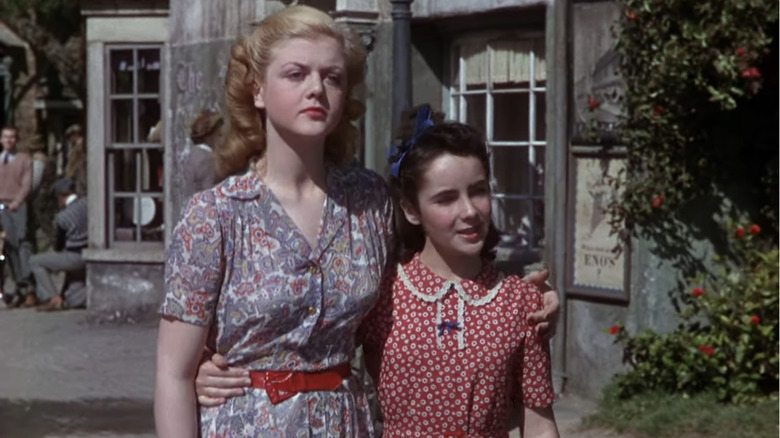

National Velvet

A few months before "The Picture of Dorian Gray" premiered, Lansbury made her second film appearance in the classic children's story "National Velvet," playing the older sister of breakout star Elizabeth Taylor. Taylor, who was 12 years old at the time, plays Velvet Brown, a horse-crazy young girl living in a small English town who comes into the possession of a spirited but untamed horse named "the Pie." She enlists a bitter ex-jockey (Mickey Rooney) with a mysterious connection to her mother (Anne Revere) to help train him for the greatest horse race in the nation, the Grand National, but when the jockey they hire to race Pie lacks conviction, Velvet takes the reins herself.

More than the size of the part, which isn't much, Lansbury's role here is notable as the only time she ever really played a young girl on screen. Despite being just 17 when cast in "Gaslight," she was never really a "child actor" as we think of the term; all of her early roles with the exception of "National Velvet" are very much adult parts in mature films. As Edwina Brown, she does well as always, but the film belongs to Taylor, who gives a star-making performance. "National Velvet" and "The Picture of Dorian Gray" were up against each other at the 1946 Oscars; Revere won Best Supporting Actress for playing the wise Mrs. Brown, beating out her on-screen daughter Lansbury.

Beauty and the Beast

In the midst of creating one iconic character on television with Jessica Fletcher, Lansbury created an entirely different iconic character on film, voicing enchanted teapot Mrs. Potts in Disney's 1991 classic "Beauty and the Beast." The story of a bookish French beauty (Paige O'Hara) held prisoner by a vain prince trapped in the body of a hideous beast (Robby Benson), it is in a way the first film of the so-called "Disney Renaissance" of the 1990s, proving that the artistic and commercial success of 1989's "The Little Mermaid" was no fluke. Lansbury lends her Broadway pipes to Alan Menken and Howard Ashman's brilliant songs, from a verse on the showstopper "Be Our Guest" (featuring Jerry Orbach doing his best Maurice Chevalier as lusty candelabra Lumiere) to singing the heartfelt title song.

Lansbury would reprise her role as Mrs. Potts several more times over the years, in the direct-to-video sidequel "The Enchanted Christmas" and in video games such as the "Kingdom Hearts" series. She also performed the title song at the opening of Disneyland Paris (then known as Euro Disney) in 1992 and at the Oscars that same year, where the film was nominated for Best Picture and won Best Original Song. In the following years she would narrate and host a number of Disney specials, including a segment in "Fantasia 2000," becoming a real-life ambassador of "Disney Magic" in a way the company had not had since the death of Walt Disney in 1966.

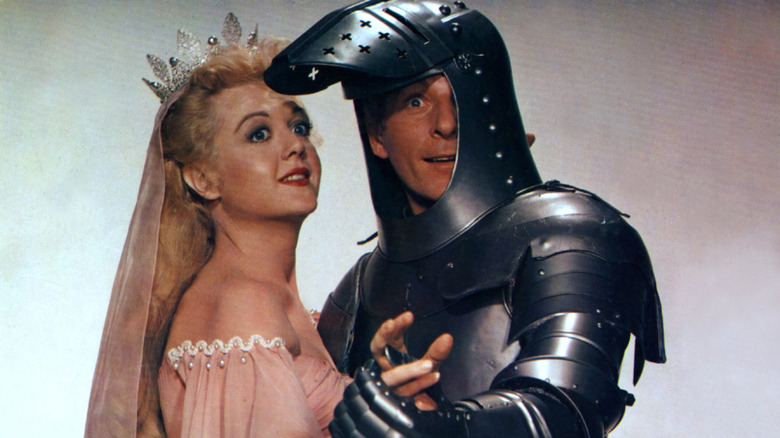

The Court Jester

Danny Kaye sends up the entire medieval swashbuckler genre in 1955's "The Court Jester," a madcap parade of mistaken identities, secret identities, false kings, swordfights, and weird tattoos on babies. Kaye stars as Hubert Hawkins, a follower of famed English outlaw the Black Fox (Edward Ashley) and his band of rebels, who are fighting to restore the monarchy to its rightful heir, a baby with a birthmark on his backside shaped like a purple pimpernel. The man who currently sits on the throne is Roderick the Tyrant (Cecil Parker), a pretender who plans to shore up his claim as king by marrying his daughter Gwendolyn (Lansbury) to a boorish lord. When Hubert and fellow Black Fox rebel Maid Jean (Glynis Johns) encounter an Italian court jester on his way to the castle, they knock him out and send Hubert in his place.

And that's not even the half of it. The film, written and directed by Bob Hope collaborators Melvin Frank and Norman Panama, has a lot of fun with sending Kaye off in multiple directions at once, as in the scene when a hypnotized Hubert romances Lansbury's pouty princess, believing himself to be a great lover and fighter, only for the spell to be broken anytime someone snaps their fingers. As with many parodies, the film was a flop when it was first released, despite solid reviews, but has grown in stature over the decades as one of Kaye's best and a bright spot in an otherwise underwhelming era of Lansbury's career.

The Manchurian Candidate

Despite being twice nominated for an Academy Award in her first three films, Lansbury's on-screen career had its ups and downs. A particular down period was for much of the 1950s, when, despite bright spots like "The Court Jester" and "The Long, Hot Summer," most of her films were uninspired and she was turning more and more to television work. Her fortunes changed, however, starting in the early 1960s, first with the William Inge adaptation "The Dark at the Top of the Stairs" and then with 1962's "The Manchurian Candidate." John Frankenheimer's classic of political paranoia, about a former Korean War POW (Laurence Harvey) brainwashed to be a sleeper agent and his former commanding officer's (Frank Sinatra) quest to save him, remains a taut and incisive thriller, one that proved unfortunately prescient — not just because of the wave of high-profile assassinations that came later in the 1960s, but also the conspiratorial thinking that it brought along.

Lansbury plays the film's main villain, the duplicitous Eleanor Shaw, who uses her son Raymond (Harvey) as a literal weapon against her political enemies. The mechanics of Eleanor's plan — to get her husband (James Gregory) nominated for Vice President, then have Raymond shoot the presidential nominee, allowing his step-father to assume the presidential nomination and institute a communist-friendly authoritarian dictatorship once in office — is perhaps overly complicated, but her performance is a thing of Freudian beauty: motherly and seductive, nurturing and deadly, all at once.