2001: A Space Odyssey Facts That Are Out Of This World

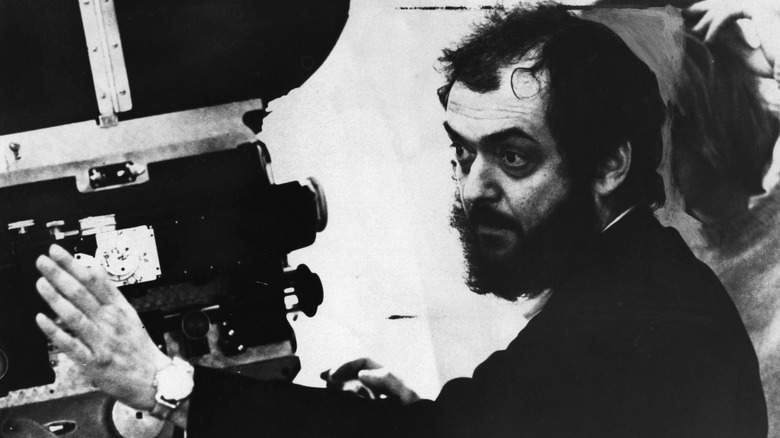

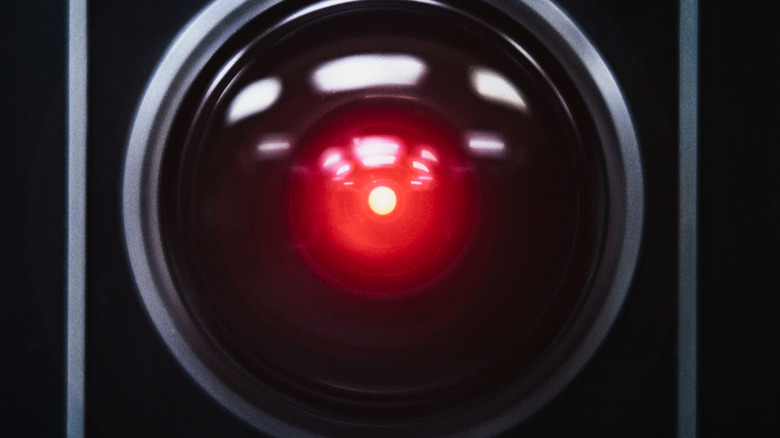

Images from "2001: A Space Odyssey ” exist in a movie space reserved for iconography like Indiana Jones' whip or Princess Leia's hair buns. It's so well known, movie fans who've never seen the film could probably look at HAL 9000 and recognize the little red-eyed computer is part of something truly timeless. The movie, directed by the legendary Stanley Kubrick, depicts humanity's interactions with aliens at separate points in human evolution. However, it's probably best remembered for its showdown between a pair of astronauts and a murderous sentient computer.

The movie's heady themes, stunning visuals, and clinical precision impacted filmmaking like a rock hurled into a placid pond. Its ripples are still making waves in the industry today. Not surprisingly, it took a lot of work, creativity, and luck to produce a movie at the scale of "2001." In fact, at multiple points in production, industry folks wondered if Kubrick and company could ever get the movie wrapped (via Vanity Fair).

Luckily for us, they completed the movie and delivered not only one of the best stories put to the silver screen, but also some of the wildest production legends. Read on to find out more about the galactic undertaking that led to one of the greatest movies of all time.

The script's long journey

Throughout his career, Kubrick clearly enjoyed adapting novels into movies. He drew upon source material ranging from pop-fiction like Stephen King's "The Shining" to more serious college English class fare like Vladimir Nabokov's "Lolita." Like many of Kubrick's other works, "2001" is based on prose. Unlike the other adaptations, the novelization of "2001" was written alongside the film's production.

Kubrick, inspired to write a movie about space travel and the possibilities it might present for the human race, linked up with sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke to work on a story together. Kubrick optioned some of Clarke's short stories and the two men agreed to work together to collaborate on a story that Clarke would turn into a novel while Kubrick turned it into a movie (via The New Yorker).

While both Clarke and Kubrick were creative geniuses in their own right, they had a hard time actually finishing the film's official screenplay. According to a 1966 New Yorker profile on Kubrick and his Herculean effort to bring "2001" to the big screen, Kubrick estimated that he and Clarke spent "an average of four hours a day, six days a week," writing the script. However, the film's release was delayed until 1968 and a Vanity Fair feature confirmed that some of the plot's "sticking points" were worked out on set. Whether there was a definitive method to the writing madness or not, Kubrick, Clarke, and company wound up with an impressive story.

An atmosphere shattering lunch

Clarke and Kubrick first met one another to discuss "2001" in 1964 at a — get this — Trader Vic's location in New York City (via Vanity Fair). For the unfamiliar, Trader Vic's is an international chain of tiki-themed restaurants and bars. Like the rest of their establishments, the since-closed New York location was decked out with gaudy island decorations and offered a bevy of tropical themed drinks.

A Vanity Fair deep dive into the making of the movie describes a successful first meeting between the two creatives. It explains that even though Clarke and Kubrick met for lunch they wound up in a conversation that stretched to eight hours. The exact details of the meeting are lost to time, but it's fascinating to think about the irony of such a cheerfully kitschy locale serving as the birthplace of "2001." Chain restaurants are a decidedly earthbound setting, yet one housed the conception of one the most cosmic movies ever made. It even sounds like a joke Kubrick might've included in a movie.

Insuring an alien encounter

The narrative thrust behind "2001" is the idea that sooner or later, humans are going to have a close encounter of the third kind. It was a timely question — during the movie's early production in 1964, a NASA space probe named the Mariner 4 was on its way past Mars (via The New York Times). Kubrick was so confident the discovery of extraterrestrial life was imminent, he began to fret that NASA would encounter something on the Red Planet before his epic was finished. Worried at the possibility of losing creative license on a story about NASA pilots meeting alien intelligence in deep space, Kubrick decided to check if he could take out an insurance policy on his own story.

In his book, "Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece," author Michael Benson explains that Kubrick found a company that would offer him insurance, Lloyd's of London (via The New Yorker). In the end, Kubrick purchased the policy, even though it came with a galactic price tag. While the human race is yet to definitively meet extraterrestrials, it's safe to say Kubrick was definitely a believer. He and Fox Mulder would've gotten along swimmingly.

Optimism for all mankind

Kubrick found his first enormous hit directing 1960's "Spartacus." He followed that success with a black comedy about the existential threat born from the nuclear arms race, "Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb." It's a funny and devastating satire that's often imitated, but has never truly been repeated.

In a 1966 profile on the director for The New Yorker, author Jeremy Bernstein explained that Kubrick had been inspired to make "Dr. Strangelove" after researching nuclear defense policies and taking them to their "extreme limits." Spoiler alert — the world blows up at the end of "Dr. Strangelove." For proof of Kubrick's pessimistic outlook on the dangers of nuclear war, Bernstein quotes the director saying, "The nuclear strategists who make up all those war scenarios are never as inventive as reality, and political and military leaders are never as sophisticated as they think they are."

Bleak stuff for sure, but it's entirely in line with the central thesis of "Dr. Strangelove." However, Bernstein argued that Kubrick found "limited optimism" in the space race. Kubrick felt the opportunities presented by space exploration and alien contact just might save the human species from itself. His belief in the power of space exploration is all over "2001." From its beautiful soundtrack to its depiction of man's divorce from earthbound technology, Kubrick clearly thought that mankind's ventures into space were full of intriguing potential.

Designing the future

Depicting the future on screen is no easy feat. In order to create a future audiences may find plausible, Kubrick created a think tank to speculate as accurately as possible. In a profile on the director, The New Yorker tallied up Kubrick's pre-production ensemble: 35 artists and designers, a special effects team more than 20 strong, and several consulting scientific advisers. This platoon of forward thinkers worked to ensure the designs of everything — from spaceships to wardrobes to cutlery — might be futuristic in a totally believable way. They definitely had some success.

The film's images are stunning and Kubrick and his design crew even picked a few aesthetics that are still popular to this day. For example, in a feature on the film's lasting impact in The New Yorker, writer Dan Chiasson noted the movie's use of Arne Jacobson flatware, a brand made famous by the movie that's still bought and sold today.

Clearly, Kubrick's attention to detail paid dividends. While many filmgoers may not remember a full, detailed play-by-play of the movie's sprawling plot, they'll likely remember the hyper specific aesthetic Kubrick curated to bring his vision to life.

Faking gravity

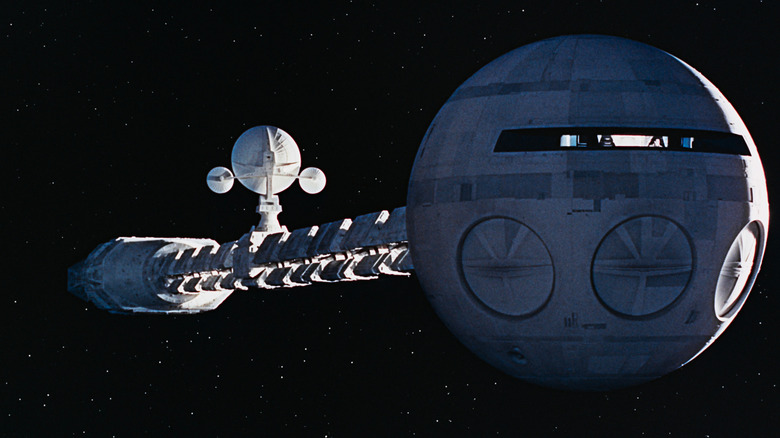

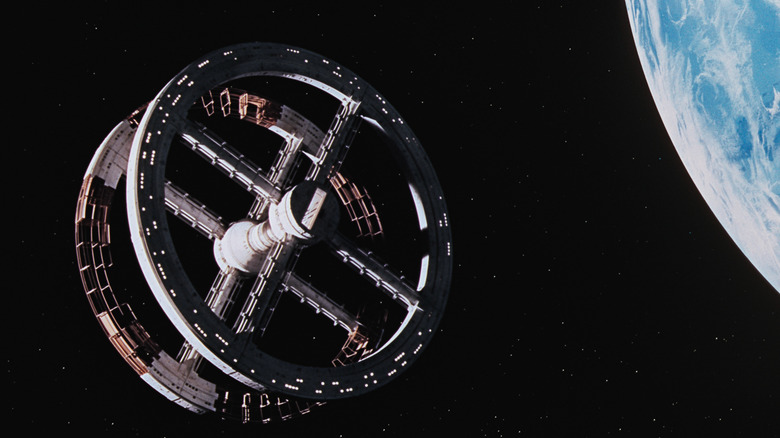

One of the movie's most iconic features is the "Discovery One," the NASA exploratory vessel headed to Jupiter in search of an alien radio signal. In the film, Kubrick handles the spacecraft's introduction with a level of care usually reserved for human protagonists. Its grand design fills the screen as it drifts slowly into frame. Then the movie cuts to the ship's distinctive interior: a centrifuge decorated with beds, work stations, a dining table, computers and more.

Kubrick — along with contemporary spacecraft designers — felt long voyages through space (like the one depicted in "2001") would require artificial gravity to keep astronauts healthy (via The New Yorker). Many also agreed — including Kubrick — that gravity could be easily created with the aid of a centrifuge. So, Kubrick hired an engineering company to build one. The finished product could spin up to three miles an hour (which didn't create enough force to keep things pinned to walls, but did create amazing visuals), cost $300,000 (before inflation), and came in at about 38 feet in diameter (via The New Yorker).

The end result is not only one of the most interesting sets ever designed, but a wonderful symbol for Kubrick's ultimate vision. Like "2001" itself, the centrifuge set is large, expensive, man made, and very hard to forget.

A classical soundtrack

The music that soundtracks "2001" is hard to forget. Its legendary opening number — Richard Strauss' "Thus Spoke Zarathustra" — is largely inseparable from the film's title sequence. But what makes the soundtrack so special? In an episode of her podcast, "I Think You're Interesting," Vox's Emily St. James interviewed Michael Benson, who literally wrote the book on the making of the film (via Kirkus Reviews). During their conversation, they broke down what made the soundtrack stand out against other sci-fi works.

The answer, largely, lies in Kubrick's decision to use existing classical pieces instead of an original score. Benson explains the studio wanted an original score because new music coinciding with a big movie's release meant more revenue possibilities for the company backing the film (via Vox). However, Benson went on to explain that Kubrick was convinced the film should be scored with existing classical pieces.

In the end, Kubrick humored the studio by meeting with a composer named Alex North. North went so far as to record an entire score, and didn't find out that Kubrick didn't use a single note of his work until saw the film. While Kubrick's lack of communication is jarring, his soundtrack choices are phenomenal. The classical music pairs with images of humanity's possible future to create something almost timeless.

A timeless cast

Anyone who hasn't seen "2001" may be surprised to discover the movie was made entirely without any Hollywood marquee names of the '60s. Kubrick forewent hiring bankable names like a Henry Fonda or a Steve McQueen (even though the studio backing the picture, MGM, hoped he would cast someone like Fonda in one of the speaking parts). Why?

A retrospective on the film in Vanity Fair argues that Kubrick didn't cast a recognizable actor in "2001" because he viewed "brand-name movie-star charisma as counterproductive" to his vision of the 21st Century. As it turns out, Kubrick was correct. As central astronauts Dave Bowman and Frank Poole, Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood feel strikingly real. This is likely due in part to not just their talent, but to Dullea's status as an up and comer and Lockwood's small TV career. Neither of them carries the baggage of being inextricably linked in the audience's minds with any previous iconic roles. Other directors could take note: when aiming for something timeless, don't cast the face of a generation.

A death defying single take

In one of the film's most tense sequences, astronaut Dave Bowman finds himself locked outside of the Discovery One in a small maintenance pod. Bowman considers leaving his pod, spacewalking to the main ship, and climbing back inside, but he doesn't have his helmet. To get back into the ship without suffocating in space, Bowman fires himself through the pod's escape hatch into an open airlock. It's an ingenious scene that only runs about 90 seconds in total. In fact, the shot of Bowman launching into the open airlock is even shorter. However, that single shot was extremely dangerous.

A 50th anniversary feature in Vanity Fair explained how the shot was created. Actor Keir Dullea had to dive headfirst through breakaway boards from a platform two stories above the airlock set, falling down toward an upward-tilted camera to convincingly create the illusion that he was launching through weightless space. For safety, he was secured with a single rope connected to a pulley.

What made the stunt lethal? An enormous film camera was positioned at the bottom of the airlock set to capture the image in a single take. If something had gone wrong, Dullea would've crashed directly into the camera. When asked if there had been any other safety precautions besides the rope and its grip, Dullea said if the grip let go of the rope, he would've been dead. It's a lot to go through for a shot, but it is a stand out set piece in a movie full of them.

The dawn of man was hard to recreate

The "Dawn of Man" sequence that kicks off "2001" may be one of the boldest ways a science fiction movie has ever opened. In a wordless ten-minute sequence, Kubrick and company recreate primordial Earth to present the concept of extra terrestrial beings jumpstarting the evolution from ape to human. Famously, the sequence ends in an incredible transition when an ape tosses a bone tool into the air and it turns into a satellite orbiting earth.

Vanity Fair reported that Kubrick originally tried to film the sequence on location in Africa, but eventually wound up creating the set in a soundstage in Britain with a technique known as front projection. The burgeoning camera system allowed creatives to project photographic vistas directly into their shot.

But new cameras weren't the only trick up Kubrick's sleeve. The dynamite design team created credible "simian man-ape" costumes. However, despite their best efforts, the sequence went largely ignored come awards season — somewhat ironically, the Best Costume Design Oscar went to "Planet of the Apes." According to Vanity Fair, the "2001" team felt a certain amount of bitterness at losing to the hammier "Apes” costumes. While both movies are iconic sci-fi offerings, the "Dawn of Man” sequence is an underrated bit of film wizardry.

MGM's big gamble

While "2001" went on to become the biggest box office earner of 1968 (via Variety), MGM took a bit of a gamble when it originally decided to back Kubrick's project. In a making-of feature on the movie, Vanity Fair reported that Kubrick first sent MGM Arthur Clarke's 250 page draft "film-story" — in other words, the official screenplay wasn't completed — and President Robert O'Brien still agreed to back the filmmaker's vision.

Given the film's many delays, it's safe to assume O'Brien's confidence may have been tested along the way. Vanity Fair noted that MGM's original press release for the film claimed that "2001" should be ready for release by 1966. The movie was delayed until 1968, and in '66 the movie's budget increased from $6 million to $7 million. In the end, the film cost MGM around $10 million, almost double its initial budget (via Variety).

Even though the film eventually went on to find success over the course of its release year, Vanity Fair noted that the saga concluded with a shareholder revolt in which O'Brien was ousted as president. Not every gamble pays off equally, but images from "2001" like Dave's space walk are a pretty high reward.

A collaborative Kubrick

It's no secret that Stanley Kubrick earned a reputation as a bit of an obsessive control freak. Publications from IndieWire to the BBC have all offered various points of view on Kubrick's legacy and professional reputation as a director who liked to steer every aspect of a production. In his 1966 profile of the director, New Yorker writer Jeremy Bernstein described the way Kubrick inspected every prop, costume, and design choice no matter how small or seemingly trivial. This includes okaying a space age cup to be featured briefly in the film's space station sequence and asking a designer to redo a prop lion's tongue for looking too "phony."

While Kubrick's zealous commitment to details is unquestionable — the man even requested a set of human embryos from a biological supply company to ensure the film's cosmic baby was accurate (via Vanity Fair) — it's hard to know exactly how he behaved on set.

Plus, tales of collaboration on set between Kubrick and his actors definitely complicate his difficult reputation. For example, since the movie's script was unfinished at time of filming, actor Gary Lockwood suggested HAL 9000 learns to read lips (via Vanity Fair). The audience discovering the evil computer can read lips is arguably one the film's most memorable moments, and it was born of teamwork. While Kubrick's often regarded as the auteur's auteur, it's interesting to consider how much of his best work was done by putting heads together instead of standing alone.

Unflattering criticism

Even though "2001" is widely regarded as a stone cold movie classic today, initial reactions from movie critics were not particularly kind. Legendary movie critic Pauline Kael said the film was "ponderous" and "blurry" in her review for Harper's. In The New York Times, critic Renata Adler said the movie's "uncompromising slowness" rendered the film "hard to sit through without talking."

However, even with the film's eventual success, Kubrick was clearly bothered by the early negative press. In a 1968 interview with Playboy (via Vanity Fair), Kubrick expressed his annoyance, saying, "New York was really the only hostile city." He went on in the interview to blame the sensibilities of New York City's "lumpen literati" for their own aversion to his movie's sincere expression of grandeur and cosmic wonder.

While the movie certainly marches along to its own deliberate pace, it's safe to say "2001" has aged much better than its initial reviews. Today, for example, it holds a top 20 spot on the American Film Institute's "100 Greatest American Films of All Time" list.

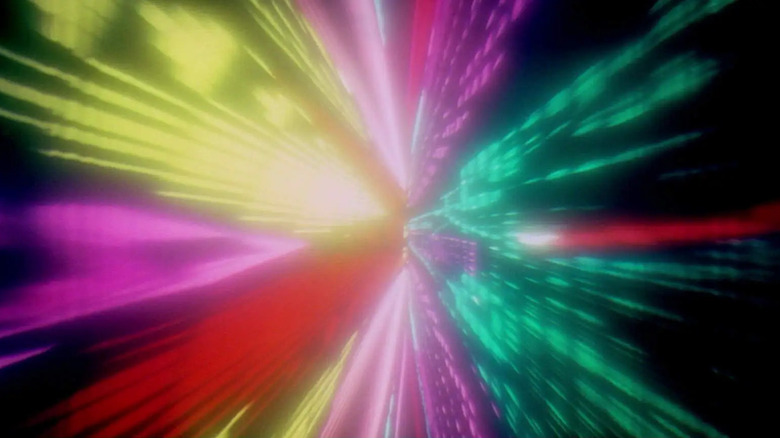

Marketing to the hippies

"2001" may not have been an immediate hit with mainstream audiences, but it definitely gained cult status with hippies. In fact, it was so popular with pillars of the '60s counter culture community (college students, rockers, aspiring artists) that The New Yorker's 50th anniversary retrospective even argues that it may have been a hippie audience that saved the film from obscurity.

Supposedly, fans of the film imbibed psychedelic drugs in sync with Dave Bowman's trip through the visually stimulating wormhole at the climax of the film. MGM's marketing gurus eventually got wind of the phenomenon and added a new tagline to posters: "The Ultimate Trip" (via The New Yorker). But word of mouth and "ultimate trips" weren't the only things bolstering the film's popularity. It also received endorsement from '60s (and eternal) rock legends like David Bowie and John Lennon. Lennon, specifically, liked it so much that The New Yorker reported he claimed to have seen it every week during its initial theatrical run.

A sun-sized impact

"2001: A Space Odyssey" not only inspired a generation of filmgoers to look up and wonder about the future, it also inspired tons of today's best filmmakers. For the movie's 50th anniversary, IndieWire collected thoughts from a collection of famous filmmakers on Kubrick's master entry to the sci-fi canon. That this list included praise from directors like Steven Spielberg, Claire Denis, Christopher Nolan, James Cameron, George Lucas, Ridley Scott, and Alfonso Cuarón should be no surprise to any film fan aware of Kubrick's lasting impact on the medium. For example, Christopher Nolan (famous for making smart spectacles like "The Dark Knight" and "Interstellar") called Kubrick "inimitable."

However, the impact of 2001 lives on outside of the elite of blockbuster filmmakers as well. A 50th anniversary retrospective in Vulture credits the film for opening up possibilities for headier, more complex sci-fi in the indie realm (think Alex Garland's "Ex Machina"). Any sci-fi movie about nefarious artificial intelligence made since 1968 owes a debt to the original murderous computer HAL 9000. Clearly, Kubrick went on his own odyssey to complete his vision. In the end, he may really have introduced audiences to new cosmic possibilities — at the movies and beyond.