The Untold Truth Of Close Encounters Of The Third Kind

In 1977, Star Wars changed science fiction forever. Before George Lucas' cinematic classic, science fiction meant one of two things — cheap, quickie cash-ins or prestigious, cerebral movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey. Star Wars used the resources of the second to hit the simple pleasures of the first, taking the action and special effects to new heights and combining them with a clear, simple story full of iconic moments and characters.

If it was the first movie of a new era, maybe Close Encounters of the Third Kind – released just a few months later with Steven Spielberg at the helm — was the last of an old era. Or maybe it was a bridge between them.

There aren't many effects sequences in Close Encounters, but they're every bit as mind-blowing as anything in Star Wars. The main focus is on the story of ordinary people touched by alien phenomena — family man Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss), single mother Melinda Dillon (Jillian Guiler), and French scientist Claude Lacombe (legendary director Francois Truffaut). The near-plotless progression of their journeys stands in the gap between the sci-fi blockbusters of the post-Star Wars world and the personal, meandering '70s movies that Star Wars' success ran out of business.

It was a long journey to bring this story to the screen, full of strange phenomena in its own right. Here are a few of those untold tales.

Spielberg wanted Steve McQueen to star in Close Encounters of the Third Kind

Close Encounters is a true ensemble piece, closer to Nashville and the other talky classics of contemporary director Robert Altman than a modern sci-fi blockbuster. But among all these characters, the most essential is Roy Neary, whose obsessive search for answers — sometimes inspiring, sometimes frightening — is the heart of the whole story. So picking someone to play him was absolutely key to the film's success.

In The Making of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Steven Spielberg and Richard Dreyfuss list a number of '70s stars considered to play the part of Roy. And these actors were so varied that it suggests Spielberg really didn't know who his hero was when he started making the film: Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, and Al Pacino. In fact, Spielberg's first choice was an icon of a whole other era — Steve McQueen, the stoic, blue-eyed star of '60s classics like Bullit, The Great Escape, and The Magnificent Seven.

However, when Spielberg met McQueen in a bar to talk things over, the star admitted he couldn't play Roy because he couldn't cry on camera. Spielberg wanted McQueen so much he offered to cut out the crying, but McQueen insisted that was the best part. He said it almost made him cry reading it, but he knew he wouldn't be able to deliver that emotion on film.

Teri Garr got the role from a coffee commercial

It's hard to imagine Dreyfuss' performance would've been nearly so great if he didn't have Teri Garr to play off of. As Roy's wife, Ronnie, Garr delivers a relatable, frighteningly intense performance that makes the breakdown of the Neary family truly heartbreaking.

Garr had already proven herself as an accomplished comic actress in both movies and TV, most memorably as Inga in Young Frankenstein. But none of those roles caught Spielberg's attention. Instead, he noticed her in a commercial for MJB Coffee. In The Making of, Spielberg explains, "I said, 'My god, there's a typical American suburban housewife.' ... I had no idea she was such a gifted actress and comedian. ... I just liked her in the commercial. She was full of these little quirky moments — 30 seconds to sell coffee and also distinguish yourself as a complete personality, and as your own personality, I thought that was amazing, what she did with such economy."

Fortunately, someone on the set was more familiar with Garr's work outside that commercial. She offhandedly mentioned one of her earliest bit parts in a movie called Red Line 7000 to co-star Francois Truffaut. As it turned out, that was one of the last movies directed by one of Truffaut's idols, Howard Hawks. Garr was shocked to learn Truffaut knew exactly what she was talking about, and he could even tell her exactly what scene she was in and recite her one line word for word!

Spielberg had to call a mathematician to convince John Williams

Close Encounters reunited Steven Spielberg with composer John Williams, who he'd met on his feature debut, The Sugarland Express, and who would score nearly all the director's future films. Williams has a unique knack for iconic themes — you can probably hear the cues he wrote for Harry Potter, Star Wars, Jaws, Superman, and Raiders of the Lost Ark just looking at those titles. The five-tone piece the aliens use to communicate in Close Encounters is just as immediately unforgettable as any of them. But it took some doing to get there.

Williams and Spielberg had many arguments over how many notes to use. Williams thought it would be easier to write seven or eight, but Spielberg insisted on limiting it to five to make it seem more like a brief greeting than an actual melody.

After trying hundreds of five-note combinations, Williams was ready to give up, sure he'd exhausted every possibility. But Spielberg wouldn't take no for an answer, so he called up a professional mathematician to ask how many possible combinations existed. The mathematician came back with an answer in the hundreds of thousands, which seems to have squashed Williams' objection pretty quick. The composer finally came up with the notes that made it to the screen — in his words, "In exasperation ... we finally said, 'I guess that's it, it must be the best we can have.'"

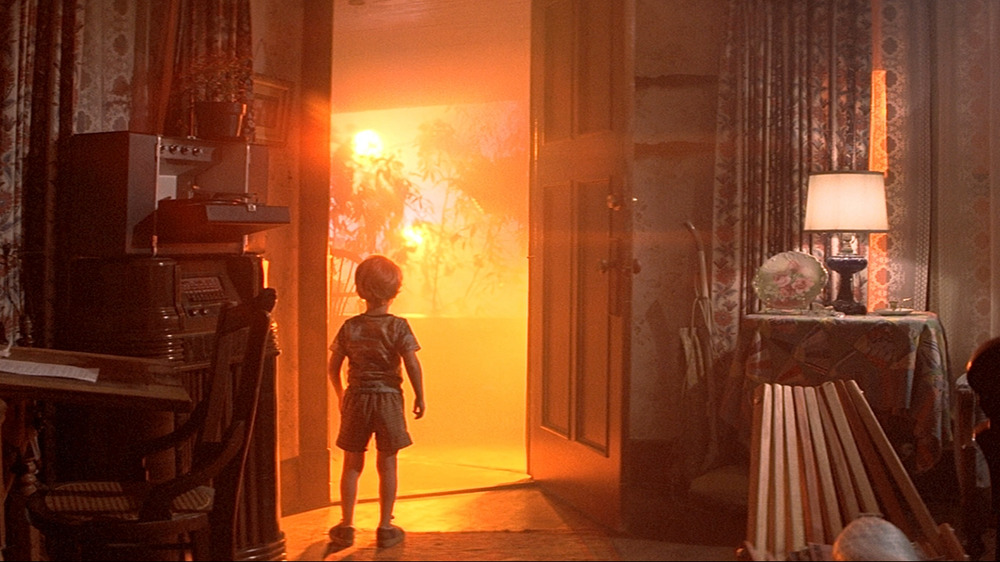

Spielberg had to be creative to get a toddler to act

In addition to its main players, Close Encounters also features Barry, Melinda's child who's abducted by aliens. Spielberg picked young Cary Guffey for the part — so young, in fact, that he was in a movie before he'd ever seen one.

As you'd imagine, it took a little imagination to get such a natural performance out of such a small child. In one early scene, Barry reacts to an alien presence somewhere offscreen. To get the appropriate sequence of reactions, Spielberg hid two crewmembers, one dressed as a clown and the other as a gorilla, under cardboard boxes. The costumed crewmembers then came out one at a time to get the right shocked reaction. Then, to get Guffey to smile, the makeup man — who'd befriended him — took off the gorilla mask to reveal his face. As Spielberg says in The Making of, "You can't do that twice."

To get Guffey's face to light up when the spaceships landed, Spielberg put a present on a stepladder and slowly unwrapped it in front of him, which is why he shouts, "Toys! Toys!" which wasn't in the script.

Guffey didn't always get the message, though. To film the ending, where the aliens return him and then leave the planet, Spielberg told him to act like he'd never see his friends again. But since Guffey had been separated from his real-life friends throughout the shoot, he thought Spielberg meant he really would never see them again and started crying real tears. Fortunately, that was just what the scene needed.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind had a massive set

At its heart, Close Encounters is a small movie about ordinary people wrapped up in a big movie about visitors from another world — a very big movie, as it turns out. At the time, the landing site for the mothership was the largest indoor set ever built. Spielberg had a vision of a military base thousands of feet long, big enough for the UFOs to use as a landing strip. After a global search, he found the only place that could house this monster was an abandoned base in Mobile, Alabama, one that the Air Force had used to build blimps in World War II. Even that wasn't quite big enough, so the crew extended it further, with scaffolding that stretched eight stories high.

Filming in such a big set caused some equally big problems. In a giant metal enclosure in the heart of the South, full of high-wattage stage lights, temperatures could reach as high as 140 degrees Fahrenheit. And designer Joe Alves tells a story in The Making of, saying, "We would have these unbelievable summer storms. ... I heard this crack of thunder, and I walked deep into the set. And suddenly a little pinhole of light appeared. And then it got bigger. And then it just exploded." Half the whole hangar blew off in the storm in the middle of the shoot and went flying off into the air.

The early spaceship designs went commercial

Many critics have dismissed Spielberg as one of the most childishly sentimental filmmakers to have ever come out of Hollywood, and even the man himself admits that he's embarrassed by how optimistic his vision for Close Encounters was. But at one point, he considered showing off a more wickedly cynical, satirical side with the designs of the alien spaceships. He had an idea that the extraterrestrials would try to make earthlings feel at ease by disguising themselves as comforting, familiar images. And by studying the Earth, they would've gotten the idea that the best way to do that would be flying in giant corporate logos.

To get this and other ideas off the ground, Spielberg poached talent from 2001: A Space Odyssey — specifically special effects wizard Douglas Trumbull, since he was the only one who lived in Los Angeles. In The Making of, Trumbull shares some early sketches based on this concept, including two ellipsoid crafts that would intersect to form McDonald's' golden arches, two others that could line up to form the Chevron logo, and an orange globe based on the 76 gas station franchise.

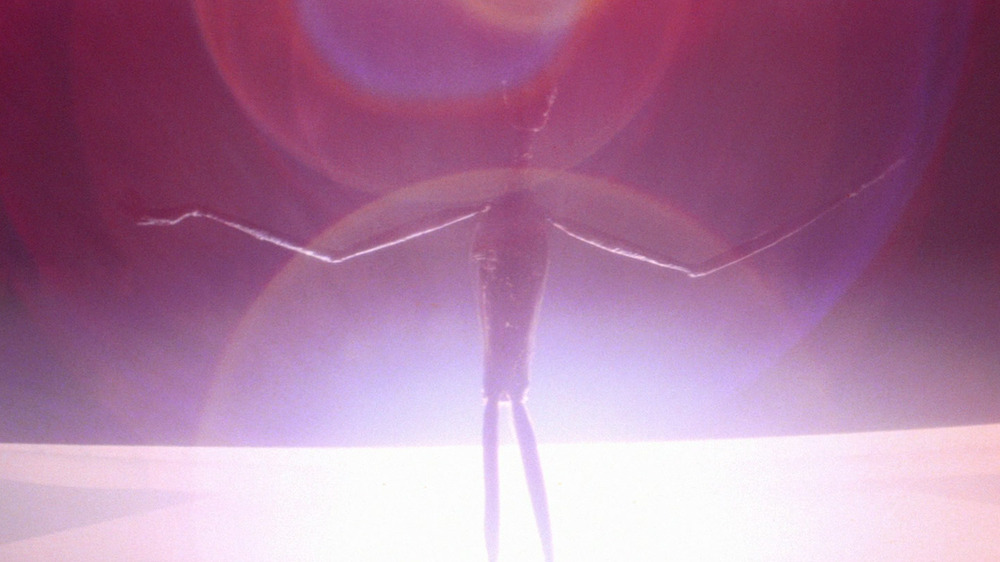

The mothership almost looked totally different

If there's one thing people think of when they remember Close Encounters of the Third Kind, it's the mothership, an unthinkably massive UFO all lit up like the world's coolest Christmas tree. But Spielberg originally imagined taking the exact opposite approach — a matte black spaceship without any lights at all, less a presence than an absence. Or as Spielberg himself put it, "A hole in the heavens, blanking out the stars."

But then he went to Mumbai to film the scene of the Indian crowd singing the alien tones. To get to and from the set every day, he had to drive past a huge oil refinery, covered in lights, tubes, and pipes. And yeah, the sight radically changed his idea of the Close Encounters mothership. He described his new vision as "a city in the sky," and he gave the brief to Star Wars designer Ralph McQuarrie. Special effects man Douglas Trumbull took that description seriously, saying he wanted those pipes and tubes to "subliminally suggest scale by looking like New York skyscrapers." To make the neon lights inside the miniature model visible, the crew — even Spielberg himself — had to pitch in and drill hundreds of little holes in all those tubes.

Barry had to wear ballet slippers for a very practical reason

Spielberg has said Close Encounters was revolutionary for suggesting for the first time that alien visitors might actually be benevolent. But what really makes the movie so unforgettable is the ambivalence of their intentions. They may want to peacefully communicate and share their wisdom in their own inscrutable way, but their presence is played for horror all through the film's first half. And we never really do understand what they want or whether the turmoil they've caused Roy, Melinda, and their families was worth it.

At the end, the aliens release everyone they've ever abducted, including pilots from World War II and some people who may be even older, but none of them have aged a day. They also reunite Melinda with Barry. This caused an acting challenge for little Cary Guffey since the ship's gangplank was made of slick glass. To keep him from falling flat on his face, he had to wear ballet shoes, and in The Making of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, he recalls that, as a four year old boy very concerned with making sure everyone knew he was a boy, he was not happy about it at all.

Spielberg had some weird ideas about the Close Encounters aliens

After making audiences wait two hours to see the aliens, Spielberg definitely wanted to deliver when they finally appeared. He didn't want to just do men in rubber suits like every other filmmaker, so he came up with a unique idea to make the extraterrestrials' movements look truly alien — orangutans in spandex suits. And then he went one step further and put them on roller skates so they'd look like they were floating down the ramp.

It went about as well as you'd expect. The handlers would push their orangutans down the ramp, and then the orangutans would jump right back into the handlers' arms. Spielberg says it was "almost like a taffy pull" as the cycle kept repeating, and the handlers would try to push the orangutans out again, and the orangutans would jump back to them again as soon as they'd let go, even as more handlers ran in to get the big apes down the ramp. Once they finally got an orangutan down the gangplank, it immediately ripped its rubber head off and threw it away and started roller skating backwards. Finally, after five minutes, Spielberg realized this "wasn't gonna work."

The crew went through many other plans for the aliens

Getting the aliens to the screen took a lot of brainstorming. After the orangutan fiasco, Spielberg tested 70 enormous marionettes with the puppeteers standing above them on scaffolding. But with all the lights shining on all those strings — 500, by Spielberg's count — there was no way to keep all of them from showing up on film.

In the end, Spielberg went with people in suits after all. But to keep the idea of alien movements, he cast a team of little girls, trained to move gracefully by a professional dancer, and he padded their costumes to "reshape the configuration of their bodies a little bit so they wouldn't look too human."

But there were still more ideas to try. Spielberg shot the footage in slow motion so the aliens would look like they were buzzing around like flies when it was played back at normal speed. He encouraged the girls to shuffle their feet and wave their hands to accentuate the effect and hired professional mimes to move slowly around them as the "normal-speed" technicians. But after months and months of takes, Spielberg was never able to get it to look like anything but sped-up footage of little girls moving at normal speed and adults moving very slowly.

E.T. was born on the Close Encounters set

If Close Encounters doesn't have the high esteem it did when it came out, that may be because Spielberg himself overshadowed it with his masterpiece of alien contact, E.T. the Extraterrestrial. There are many similarities between the two movies, from the realistic portrayal of Midwestern, suburban life and the evocation of childlike wonder to the designs of the aliens and their ships. So it may not surprise you to learn we never could've had the one without the other.

In Steven Spielberg: 30 Years of Close Encounters, the director details the moment that E.T. came to him, right there on the set of the earlier film. "I thought, 'Wait a second, what if that extraterrestrial didn't go back on the ship? What if it was a foreign exchange program and the astronauts ... go up on the ship with Richard Dreyfuss in exchange for one extraterrestrial staying behind as an ambassador in good faith?' And I began to think about — should I change my movie right now? And then I thought, that notion really jives with this imaginary friend concept I've been working on all my life."

The two ideas combined into E.T., and along the way, the alien ambassador turned into a little lost creature trying to find his way home. So it turns out we all have Spielberg's mind wandering on the set of Close Encounters to thank for one of the greatest family movies ever made.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind's controversial new scene

Close Encounters of the Third Kind opened for the 1977 holiday season to enormous financial success and universal acclaim. But it still wasn't finished, at least not the way Spielberg wanted it to be.

He thought it would take until the next summer to complete, but his bosses at Columbia needed a hit. They were facing bankruptcy and worried that getting Close Encounters out by Christmas was the only way to save the studio. So Spielberg and his crew had to rush the film across the finish line to meet their due date.

Spielberg says he came back to Columbia once the box office had done its work nearly two years later to ask for more time to recut and reshoot Close Encounters. Columbia agreed, but they wanted some big, flashy reveal to justify the expense. They wanted the inside of the mothership.

It was a painful decision. Close Encounters got its power by depending on the imagination to fill in the details. But Spielberg agreed to film that unnecessary scene in exchange for the scenes he thought were necessary. In 30 Years, Spielberg calls it "a deal with the devil," and he says, "I didn't want to see it."

Spielberg finally got the deal he wanted decades later with a third edition that restored these scenes without the inside of the mothership. But no matter what form it's in, Close Encounters of the Third Kind remains a timeless classic.