Here's Why The Simpsons Season 34 Premiere Takes On Conspiracy Theories

The 34th season of "The Simpsons" — the longest-running scripted series on American television — premiered on September 25. As usual, it tackled an all-too-relevant social ill with humor, balance, and poignant commentary.

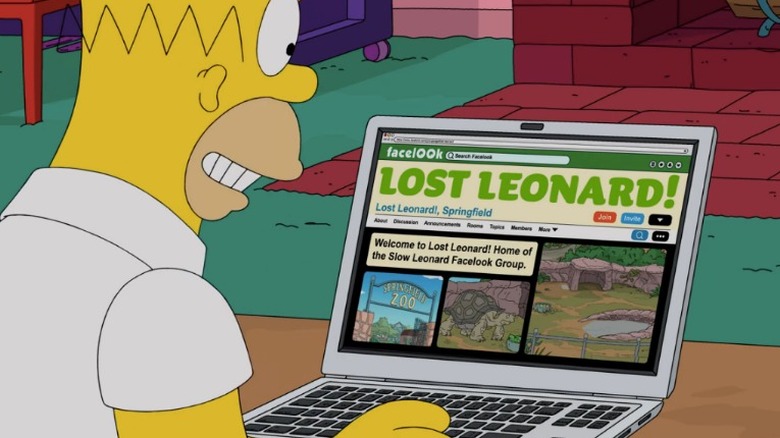

In "Habeas Tortoise," Homer (Dan Castellaneta) is ashamed after his neighbors very publicly come down on him for saying something dumb at a town hall meeting. In his isolation and dejection, he turns to "Facelook," where he finds comfort, encouragement, and a sense of community and confidence with a group of internet sleuths trying to crack the case of the supposed disappearance of the Springfield Zoo's Slow Leonard, a 150-year-old tortoise. Curiosity quickly devolves into conspiracy, and the instantly tight-knit group's "there are no bad ideas" ethos evolves (just as quickly) to include and promote even the zealous and violent. Meanwhile, Homer's family looks on helplessly as his identity becomes irrevocably intertwined with the group and their increasingly confused and dangerous beliefs and schemes.

In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, executive producer Matt Selman shared his thoughts on the episode's approach and purport — and on the evolution of the conspiracy theory itself and its place in society — and made clear that the point was not simply to poke fun, but to investigate and demonstrate how such a volatile evolution comes to pass.

Habeas Tortoise tackles the complexity of conspiracy

"Ultimately," Selman told the outlet, "people just want to feel like they're part of a community of people that respect each other ... they've been told they're dumb, so they formed these very intense communities with very intense specific belief systems." It's a motivation the episode makes abundantly clear: "Oh my god," Homer notes with astonishment and delight: "A group of anonymous cyber sleuths don't think I'm an idiot!"

This revelation is the catalyst for the episode's events, Homer's spiral, and, according to Selman, the crux of what the premiere seeks to unravel. "We're trying to explore the emotional dynamic of how conspiracy cults become so fervent," he said, adding, "Obviously we're making fun of conspiracy-theory social-media fervor. But at the same time, we wanted to have a relatable [episode] about the human element of it all."

The Slow Leonard group's collective and contagious belief in its own worth is at the heart of the psychology behind these theories' appeal, as a study from the University of Kent explains. "[Conspiracy theories] help to uphold the image of the self and the in-group as competent and moral but as sabotaged by powerful and unscrupulous others," it reads. "If this is the case, we can expect conspiracy theories to be particularly appealing to people who find the positive image of their self or in-group to be threatened (Cichocka, Marchlewska, & Golec de Zavala, 2016)." This effect is also on full display in the episode ...

As always, The Simpsons' social commentary is layered

"Do you know how scary it is in this climate to be a dumb white man," Homer asks. Each time he proposes an idea, he's met with a shower of approval and reinforcement in the form of positive emojis. It's an overt but layered demonstration of the show's motivation. On the one hand, it shows, as Selman says, "Empathy for why people feel so connected to these groups;" on the other, it exposes the artificiality and narcissism behind that connection.

Of course, "The Simpsons" can't help but give viewers an open window to accompany a closed door, and "Habeas Tortoise" is no exception. In the end, we learn that the company that makes the bulletin boards, thumb tacks, and universally-recognized red yarn that Homer and his theorists use to display their connections really is involved in some nefarious plotting: "Maybe the real conspiracy," Selman told EW, "is people are getting rich off selling conspiracies online."

The series' ability to cloak context and critical perspective in the guise of humor — and to balance its critique with often overlooked insight — goes a long way toward explaining its 33-year run on network television. "Conspiracies used to be entertaining," Selman explained, "[Now] what used to be kind of funny mental exercises are helping to unravel civilization."

By making them entertaining once more, "The Simpsons" Season 34 premiere shines a light on one of the most insidious elements of 21st-century connectivity, all without engaging in the kind of aggressive, counterproductive shaming Selman strove to avoid.