The Best Courtroom Scene In Law & Order: SVU Season 9

While recent seasons of the long-running "Law & Order: Special Victims Unit" have concerned themselves with ripped-from-the-headlines subjects such as "Me Too," Black Lives Matter, and the law's efforts to address advances in technology, Seasons 5 through 9 often concerned themselves with both the fall-out of 9/11 and the war in Iraq. These just so happen to be the first four seasons starring Diane Neal as legendary A.D.A. Casey Novak, a character who had her work cut out for her when she stepped in to replace the long-beloved A.D.A. Alexandra Cabot (Stephanie March). Though Novak, like Sam Waterston's Jack McCoy before her and Raúl Esparza's Raphael Barba after her, brought her share of ambitious cases to trial, she was at her most memorable when endeavoring to hold the seemingly untouchable accountable.

Such is the case in the A.D.A.'s best courtroom scene from Season 9. In the aptly titled "Harm" (Episode 5), Novak charges a doctor who helped create the torture techniques used on military prisoners in Iraq with criminally negligent homicide. After a former detainee's death is linked to the torture he suffered while in captivity overseas, Novak alleges that, as a doctor, the defendant should have foreseen that the long-term effects of her techniques could directly contribute to and ultimately result in death. Since the techniques were conceived of in New York (and not Iraq), Novak is able to bring the case to trial by citing continual jurisdiction.

What follows is one of the series' most memorable and poignant trials to date.

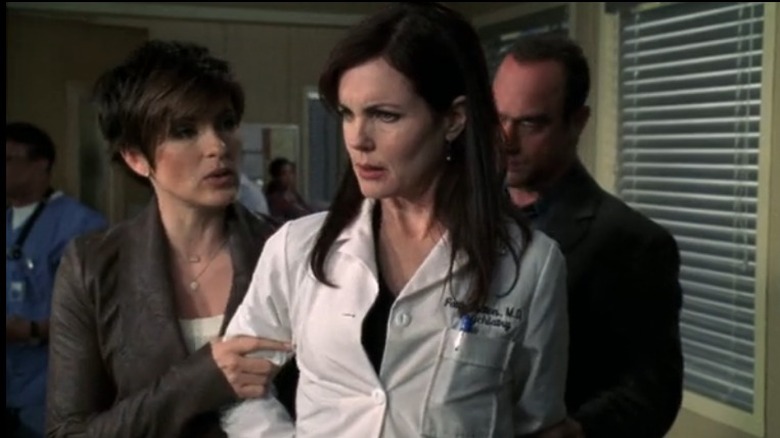

Melinda Warner teams up with Novak to take down a war criminal

In "Harm," a former U.S. soldier murders both a former innocent Iraqi prisoner and a victim's advocate — Jarreth J. Merz's Haroun Abbas and Liz Morton's Kate Simes, respectively — after he discovers Kate has been encouraging Haroun to speak out publicly about the long-term physical and psychological damage caused by his treatment overseas. Since the murderer's employer, a military contractor called Helios, helps him flee the country and escape prosecution, Novak's only means of seeking justice is to go after psychologist and physician Faith Sutton (portrayed by a pre-"Downton Abbey" Elizabeth McGovern).

Though Haroun technically died from a hypothermia-induced cardiac arrhythmia after being subjected to a prolonged ice bath, M.E. Melinda Warner (Tamara Tunie) maintains that he'd have survived his encounter with his torturer in New York had it not been for the underlying heart disease caused by the abuse he suffered in Iraq.

Warner's presence in the courtroom always makes for a compelling trial, but in "Harm," the personal and professional disgust she feels toward her colleague's participation in such cruelty only adds to the impact of her testimony. It also helps the already-relevant and timely storyline speak even more directly to the moral, ethical, and ideological questions at the heart of the episode's real-life inspiration.

Harm holds lasting relevance

When "Harm" first aired on October 27th, 2007, America was only just beginning to come to terms with its now widely-publicized torture of detainees at the Abu Ghraib prison camp (as reported by CNN). The nation caught its first, graphic glimpse of the events there only three years prior, and only one year prior, even more photos from the same place and time period began circulating, just months before the U.S. transferred its last prisoner and finally relinquished control of the camp over to the Iraqis in September of 2006. In the end, the outlet explains, 11 U.S. soldiers were convicted for their participation in the crimes, while several others received reprimands rather than charges. Though a civil lawsuit was filed against military contractor CACI Premier Technology in 2008, it would be another dozen years (that brings us to 2021) before The Supreme Court finally gave a ruling that allowed the case to proceed.

Suffice it to say, "Harm" is no less relevant now than it was when it first aired, and Novak's approach to trying the good doctor remains as compelling as ever, not least of all because it draws so heavily from reality. In 2004, the New England Medical Journal found that "the medical personnel who helped to develop and execute aggressive counter-resistance plans thereby breached the laws of war [outlined in the Third Geneva Convention]," after noting that "The conclusion that doctors participated in torture is premature, but there is probable cause for suspecting it." Nevertheless, to-date, no doctor has been legally held accountable for their participation in war crimes (via CNN).

Novak's does, and doesn't, win her case

Like all doctors, Sutton swore an oath to "first, do no harm" (hence the episode's title). Despite this, she actively participated in punishments she knew, Novak claims, would cause lasting psychological and physical harm — arguably, the very definition of torture as defined by The Geneva Convention. During the trial, Sutton puts up her best "you want me on that wall, you need me on that wall" defense, and although the courtroom scene ultimately ends in a mistrial (after Sutton dramatically saves a juror's life), the argument isn't enough to free her from all consequence.

This is part of what makes the episode, and its epic trial scene, so brilliant. "Harm" holds a participating doctor accountable in a way that real life did not (and has yet to), but it stops short of giving us an idyllic, unrealistic portrayal of justice. Sutton isn't found guilty of criminally negligent homicide, but she is condemned by her peers on the Medical Review Board, who (like the NEMJ) don't buy the blatantly contradictory argument that a physician isn't acting as a physician, but as a combatant, when they provide medical advice and instruction to the military.

In her meditation on another epic Novak episode (the one where she attempts to subpoena Donald Rumsfeld), The Cut's Opheli Garcia Lawler writes, "['Special Victims Unit'] put the avatars of the people who hurt us on trial — and it let viewers imagine a world in which incompetent and uncaring leaders propagating a war we probably weren't supposed to be in were almost forced to answer for their decisions." Season 9's best courtroom scene stands out not only for its immediate and lasting relevance, but for its credible and societally cathartic attempt to do just that.