Everything The Jurassic Park Franchise Gets Wrong About Paleontology

Much like little Tim Murphy, a great many people go through a period in their youth in which they're obsessed with dinosaurs. When "Jurassic Park" stomped into theaters in 1993, all of us were kids again as we gazed slack-jawed at the impossibly realistic, long-extinct great beasts on the screen. The film (and to a lesser extent, its many sequels) was so awe-inspiring, that a new generation of paleontologists was compelled to enter the field because of "Jurassic Park" (per NPR).

Ironically, many of those who became dinosaur experts learned the objects of their fascination weren't portrayed so realistically in the franchise after all. But Michael Crichton, who wrote the 1990 novel and co-wrote the screenplay, and Steven Spielberg, who directed the beloved adaptation, can't be blamed entirely for the film's plethora of inaccuracies. To be fair to the filmmakers (who were also advised by real-life paleontologists, per Smithsonian Magazine), some of what we know now about dinosaurs hadn't been discovered as of 1993. And since the movies themselves are more like a mash-up of tense adventure, horror, and thrills, it's probably best to think of Isla Nublar's creatures as something more akin to the monsters in a monster movie instead of actual animals that roamed the earth millions of years ago. Nevertheless, this is what the franchise gets wrong about paleontology and related sciences.

Jurassic Park is a misnomer

"Jurassic Park" is a great-sounding title for a book or movie; it's just not a very accurate name for a theme park that's home to mostly dinosaurs from the Cretaceous period. Before we get any deeper into the faulty science behind the film series, we should establish that not every big, dead reptile from the distant past is even a dinosaur, per Earth Archives. This is an oversimplification, but generally, pterosaurs flew through the air, dinosaurs walked the land, and plesiosaurs lurked in the water.

The majority of the species that are featured in the movies — Ankylosaurus, Gallimimus, Mosasaurus, Oviraptor, Pachycephalosaurus, Parasaurolophus, Quetzalcoatlus, Spinosaurus, Therizinosaurus, Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops, and Velociraptor — are from the Cretaceous period, which lasted from about 145.5 million to 65.5 million years ago. The Jurassic period spanned from about 199.6 million to 145.5 million years before our current geological era. That means truly Jurassic species like Apatosaurus, Allosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Dilophosaurus would never have crossed paths with ones from the Cretaceous.

The various species cloned by InGen — from all over the globe and separated by more than 100 million years in some instances — would've required enormously different climates, habitats, and food chains to survive. Isla Nublar isn't quite diverse enough to accommodate the entire Mesozoic era's flora and fauna, and that's to say nothing of the chaos that would (and did) ensue when species that didn't evolve together are trapped on an unfamiliar island.

DNA doesn't last millions of years

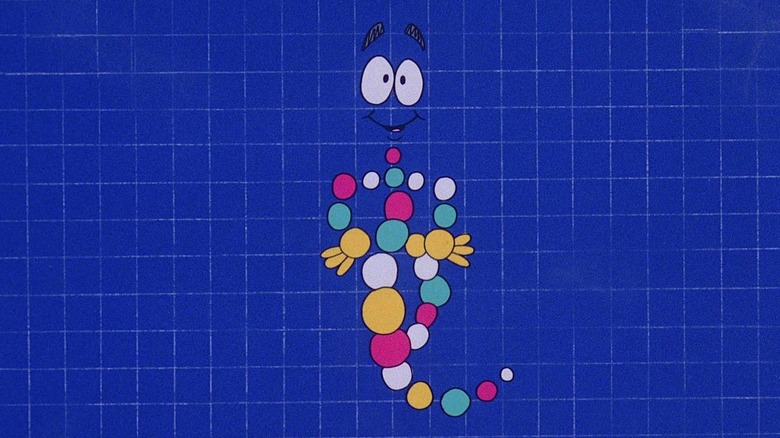

Dr. Hammond (Richard Attenborough) gives doctors Alan Grant (Sam Neill), Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern), and Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) a pre-grand opening tour featuring an introductory video starring the animated Mr. DNA (Greg Burson). He explains to the bewildered scientists and the audience how InGen's cloning process works. Dino DNA is extracted from prehistoric mosquitos preserved in amber, then genetic information from frogs completes the genomic code.

There's just one problem. DNA doesn't last for tens or hundreds of millions of years. The oldest DNA on record is from a mammoth found in Siberia that's believed to be around 1.6 million years old (per Nature). That mammoth's genetic strands were kept intact not by a bloodsucking bug in amber resin but by three teeth covered in permafrost. Prior to this discovery, the oldest known DNA belonged to a horse from about 560,000 to 780,000 years ago (per Nature). That's a long time, but it doesn't get us back to even the Cretaceous period by a long shot.

Scientists have calculated that DNA has a half-life of 521 years (per Nature), which means that genetic sequences would barely be readable even in a perfectly preserved fossil after about 1.5 million years (the mammoth find pushed this type of research to its limits, per Nature). They'd completely disintegrate by 6.8 million years — still about 10 times too quickly to bring back a dinosaur — which makes Hammond's dream of cloned dinosaurs, sadly, impossible.

That's not a prehistoric mosquito in the amber

We've already touched upon the fact that InGen's cloning process wouldn't actually work, but even if it could, Dr. Hammond wouldn't be able to siphon any dinosaur DNA from the insect that's trapped in his amber staff. In the first "Jurassic Park," the species of mosquito that's depicted in the lab is a Toxorhynchite, more commonly known as an elephant mosquito (per Mail Online). It is the biggest known species, which is probably why filmmakers chose it, but unfortunately for InGen's technicians and Hammond's investors, it's the only mosquito that feasts upon fruit and nectar instead of blood. The one the props department picked is also a male; we can tell from its hairy antennae. That presents yet another issue. Among all the other species of mosquitos, only the females suck blood with their proboscises. Thus, Hammond's mosquito is doubly unsuited for DNA harvesting.

Furthermore, the real bug is a crane fly (per Insider), designed by the prop team to emulate a millennia-old mosquito. Prehistoric mosquitos did exist, some concurrently with dinosaurs, so at least that part of Hammond's theory holds up (per The London Economic). However, discoveries of fossilized specimens dating back that far happened too late to inform the production design of "Jurassic Park" (per Smithsonian Magazine).

Those aren't Velociraptors

The dinosaur species that really got a publicity boost from the "Jurassic Park" movies was Velociraptor (sorry, Dr. Grant, their name means "swift thief," not "bird of prey"). But the real-life dinosaurs are thought to have been much different.

These late-Cretaceous theropods, which belong to the Dromaeosaurid family, were really only about the size of a turkey. Like our modern-day fowl, they were at least semi-covered in feathers. Fossils reveal bony quill knobs on Velociraptor's forearms, and other small Dromaeosaurs like Microraptor have been found with their feathers well preserved (per The Natural History Museum). "Jurassic Park III" doesn't correct for Velociraptor's scale, but it does add some scant feathers, though to the head and not the limbs.

Despite their size, they still would've been intimidating. Velociraptor did have large claws, including a sharply curved one on its second toe that was probably used to pin down prey, and they may have been relatively smart. Species like Velociraptor are the ancestors of modern birds, and birds are surprisingly intelligent (per National Geographic). But they definitely couldn't have coordinated and opened doors as they do in "Jurassic Park." Filmmakers surely supersized Velociraptor to make it properly terrifying, but in the years around and following the movie's release, raptors as big as Blue and even larger have been discovered and classified, such as the Utahraptor, which measured up to 23 feet long (per Smithsonian Magazine). That means creatures of Blue's size did exist; they just weren't Velociraptors.

T. rex's appearance and behaviors are inaccurate

Tyrannosaurus rex isn't just the king of the dinosaurs. He (well, she, according to InGen's cloning rules) is the Mesozoic era's most A-list celebrity, so it makes sense that T. rex gets the most iconic scene in the entire franchise. Filmmakers got closer to the truth with this late Cretaceous North American apex predator. T. Rex really was a hulking beast that could grow to more than 40 feet in length and weigh up to 7 tons (per the Carnegie Museum of Natural History). Its mouth had 60 serrated teeth that measured up to 6 inches long, with a bite force of about 12,800 pounds ... the strongest of any land animal ever (per Smithsonian Magazine).

Some paleontologists believe T. Rex had feathers, too (per the American Museum of Natural History). That doesn't make this enormous carnivore any less deadly, just stranger-looking. Scientists don't know for sure what dinosaurs would've sounded like, but between the fossil record and computer modeling, their best guess is that they made vocalizations closer to those of reptiles or birds (via CMNH).

T. Rex was a much better hunter than "Jurassic Park" gives him credit for, however. During its attack, Dr. Grant tells the kids to stand still because T. rex has poor eyesight. But skulls show that T. rex had binocular front-facing eye sockets (per the University of Oregon), which means it had superior vision and would've easily detected the humans right in front of it.

Dilophosaurus couldn't do that

One of the more visually arresting dinosaurs in the "Jurassic Park" franchise is Dilophosaurus. Famously, it takes out Dennis Nedry (Wayne Knight) as he's trying to smuggle DNA out of the park in a shaving cream can. It's also the species that puts an end to maniacal Biosyn CEO Dr. Lewis Dodgson (Campbell Scott) in "Jurassic World Dominion." Like T. rex, the movies made Dilophosaurus more and less scary than it would have been in real life.

As cool and cinematic as that big, retractable frill around its neck is, there's no evidence to suggest this early Jurassic therapod had one (though it did have a crest). There's also no evidence to support that it was venomous (per Science). Animals that do have poisonous saliva also have teeth with specialized grooves in them through which the venom travels, and fossilized Dilophosaurus teeth have no such grooves (per Science).

So a real Dilophosaurus couldn't have entranced then spat on Nedry the way the one in the movie did, but it still could've easily killed him. That's because this predator, which lived about 193 million years ago, was actually one of the largest of its time. It's medium-sized compared to later theropods like T. rex and Spinosaurus, but it still would've dwarfed Nedry at about 20 feet long and three-quarters of a ton (per National Geographic). That's much bigger than the ones depicted in "Jurassic Park," which are smaller than average humans.

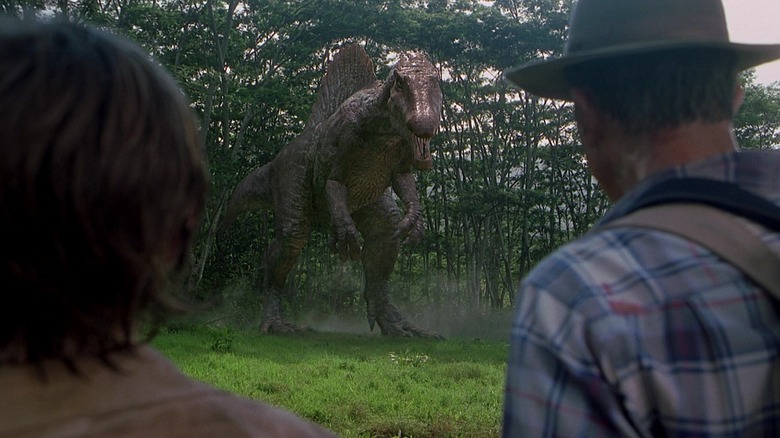

Spinosaurus deserved more respect

"Jurassic Park III" tried to one-up the T. rex the only way it could (until "Jurassic World" creates hybrids, that is): with an even bigger predator — Spinosaurus. Then "Jurassic World Dominion" introduced Giganotosaurus, which the film twice claims is the largest land predator of all time. Giganotosaurus may have been a little longer than T. rex on average at over 40 feet, though the fossil record is incomplete there (per the Natural History Museum). But Spinosaurus measured closer to 60 feet and looked even larger thanks to the tall dorsal sail upon its back, making it the longest land predator of all time and a great choice for a villain (per the Natural History Museum).

The film's physical depiction of Spinosaurus is pretty spot on. Its lifestyle, however, would've been drastically different. In the film, Spinosaurus stalks the main characters, who are only alerted to its presence because it swallowed a satellite phone that rings ominously whenever it approaches. But in reality, this theropod — which lived about 95 million years ago in what's present-day Egypt — would've spent most of its time at least partially submerged in water (per the Carnegie Museum of Natural History). Everything we now know about Spinosaurus suggests that it was an aquatic hunter. That crocodile-like snout and sailfish-like sail, plus webbed feet, shark-like teeth, and bones built for swimming all point to an affinity for prehistoric fish.

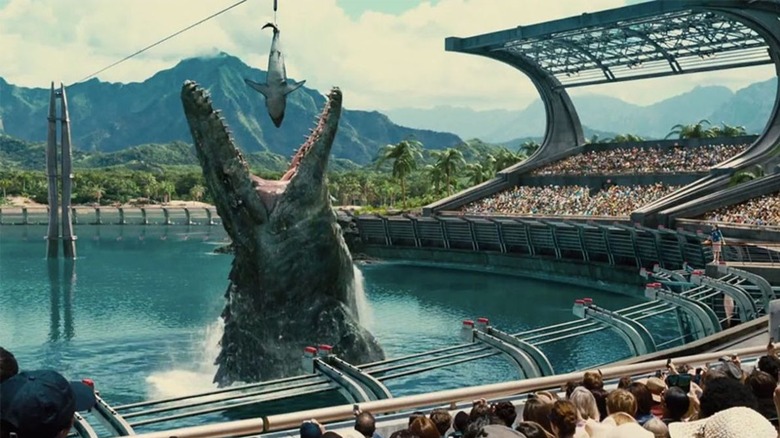

Mosasaurs weren't quite that big

By the time the fictional Jurassic World park opens to the public, InGen has cloned a Mosasaur, which it keeps in a stadium-sized Sea World-like tank. Crowds are at once astonished and horrified as the prehistoric ocean dweller emerges from below the surface to swallow a great white shark as though it's a mere goldfish. Mosasaur — which isn't actually a dinosaur — was big ... but not that big.

One would've stretched about 56 feet long (per LiveScience). The creature we see in the tank in "Jurassic World" and in the opens seas at the start of "Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom" appears to be even larger than a blue whale – the modern world's largest animal — when compared to the shark it's being fed. This is confirmed in "Jurassic World Dominion" when a wild one is seen swimming with two blue whales and is about double their size.

The reverse is true. Mosasaurs were only a little more than half as long as blue whales, which themselves can reach nearly 110 feet, (per LiveScience). But their overall body mass was much smaller; blue whales tip the scales at 200 tons (per National Geographic). The sea beast in the movies is also covered in armored plates with a flat paddled tail. A real Mosasaur would've been a little shorter and significantly thinner with a caudal fin and no armor, more like a snake (via the Philip J. Curie Dinosaur Museum).

Therapods couldn't move their wrists like that

In one of the film's most tense moments, Tim (Joseph Mazzello) and Lex (Ariana Richards) hide in one of the park's industrial kitchens while a pack of raptors searches for them on the other side of the door. Doctors Grant (Sam Neill) and Sattler (Laura Dern) assure the kids the raptors won't be able to open it. Then, clawed fingers pull down on the handle, and a sliver of light appears. Regardless of whether or not Velociraptors had the mental capacity to solve such a problem, their skeletal systems probably wouldn't have allowed them to. Velociraptors — and all therapods — have palms that permanently face each other (per Science News).

Theropods are the bipedal, carnivorous dinosaurs from which our modern-day birds evolved (per the University of California, Berkeley). Something all theropods seem to have in common is those inward-facing wrists. We know this because multiple fossilized tracks have been uncovered in which the impression left behind millions of years ago is that of the edge of a hand and not a palm print (per Science News). This is true whether the animal in question is walking or resting. If a dinosaur could take a load off by balancing on its flat palms, it would. In the "Jurassic Park" films, most theropods' hands are frequently in the wrong position. Furthermore, while Velociraptors may have had some wrist mobility, it likely wouldn't have been enough to operate a door handle (per LiveScience).

Heavy dinosaurs probably couldn't run

So far, we've focused on the "Jurassic Park" franchise's carnivores, but there are mistakes in the way its hypothetically cloned herbivores are brought to life, too. Some of them are minor; for example, the dinosaurs would've walked with their tails up instead of dragging (per The Guardian), and the headgear of Sinoceratops is ever so slightly off (per the Natural History Museum). But the most consequential error is that most heavy dinosaurs (especially long-necked sauropods, tank-like quadrupedal dinosaurs, and even the T. rex) probably weren't capable of running, as they often do from each other in the movies and from the volcanic eruption in "Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom" (per The Independent).

As dinosaurs evolved into the Jurassic period, more quadrupedal species like Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, and Stegosaurus began to appear (per The Guardian). By the Cretaceous period, Ankylosaurus and Triceratops were thudding their way around the forests. Researchers are debating about the speed of huge predators like the T. rex currently, with some claiming that it couldn't run faster than 12 mph (per National Geographic).

We don't know for sure; perhaps in the case of rapidly-approaching lava, heavy quadrupeds would've found a way to pick up the pace. But with the exception of natural disasters, most large dinosaurs wouldn't have had much use for running anyway. Some researchers say the force of their own weight while running would've crushed their bones (per National Geographic).

InGen never explains prehistoric plants

Though the "Jurassic Park" movies tend to highlight the showier carnivores, per capita, there are more herbivores on the premises, as those species tend to live in herds. All those plant-eaters need to eat, too, and paleobotanist Dr. Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern) is particularly curious about how InGen managed to bring back ferns and other foliage from millions and millions of years ago. They never really explain the process to her in the film, and her concern shifts to the toxicity of the plants that John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) keeps around because they look pretty.

Though the park's scientists couldn't have used the mosquito-amber process they used for the dinosaurs, it is possible to clone extinct plants (per NYU). Researchers brought back palm trees from more than 2,000 years ago by using genetic material from preserved seeds, and more recently, they revived a 32,000-year-old flower from a frozen seedpod (per My Modern Met). But again, 32,000 years is a blink of an eye compared to 65.5 million. The expiration date of DNA would prevent the flora upon which dinosaurs snacked from ever being reproduced.

Cloning plant life, though, might be more disastrous in the long run than dinosaurs on the loose. Invasive plant species, per the U.S. Forest Service, can spread quickly and threaten any ecosystem as they choke out native vegetation. As Dr. Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) would say, even if we could, it doesn't mean that we should.