The Real-Life Paleontology Feud That Made It Into The Lost World: Jurassic Park

The "Jurassic Park" franchise is, well, a monster: It has five films with a combined worldwide box office haul of over $5 billion, four dozen video games, a few water rides, a Lego miniseries, and even a live show. The latest on-screen property, the DreamWorks-produced Netflix show "Jurassic World: Camp Cretaceous" just finished up its fourth season, and the third part of the "Jurassic World" trilogy, "Jurassic World: Dominion," is scheduled for release in June.

Whether you call it ironic or prescient, what began in the original movie as a side-eye wink at cynical merchandising has long since hatched from its adorable little lunch pail, jumped the fence, and began stomping across the pop culture landscape. The transmedia sci-fi universe owes its existence to Steven Spielberg's 1993 hit "Jurassic Park." There are plenty of explanations for the phenomenal success of the original movie: There's Spielberg, of course, delivering his first monster movie since "Jaws"; a magnificent score from frequent Spielberg collaborator John Williams; groundbreaking CGI effects that still blow people away almost 30 years later; and well, it is dinosaurs after all — tapping into something primal in all of us, something everybody remembers being obsessed with at some point in their childhood.

Above all else, the franchise owes its success to the strength of the source material: two novels by Michael Crichton, a writer who had a knack for spinning cutting-edge scientific fact into hugely popular speculative fiction gold.

The real science behind Jurassic Park

Crichton's novel "Jurassic Park," published in 1990, provided the source concepts for the entire "Jurassic Park" universe. The author has had over a dozen of his novels adapted for film, including "The Andromeda Strain," "The Terminal Man," and "Coma." As with all his projects, Crichton did a great deal of hard research before putting pen to paper on "Jurassic Park" and its sequel, "The Lost World" (via Smithsonian Magazine).

While undoubtedly taking outrageous liberties for artistic effect, there is some serious science hiding behind (or at least inspiring) the movies. Genetic engineering, gene splicing, DNA editing, and cloning are all thriving disciplines in the 21st century. "De-extinction" efforts to bring back long-dead species may be closer to success than many people realize (via The New York Times), and corporate ownership of genetic information, or "biobanking," is a genuine bioethical controversy.

The scientific basis for a theme park of dinosaur clones may be a stretch, but the original movie did employ reputable dinosaur experts as advisors (via ThoughtCo). One ongoing controversy among paleontologists involving the true nature of the T. Rex even made it on-screen in 1997's "The Lost World: Jurassic Park."

Dr. Burke in The Lost World: Jurassic Park is based on a famous paleontologist

Dr. Robert Bakker is one of the world's most famous paleontologists, having published numerous popular books, including "The Dinosaur Heresies" and "Raptor Red," a novel depicting a day in the life of a Utahraptor. Dr. Jack Horner, also a renowned paleontologist, discovered and named a genus of dinosaur and is known for his contributions to dinosaur growth research (via ThoughtCo). Dr. Bakker believes T. Rex was a predator, while Dr. Horner believes it was a scavenger. Both men were technical advisors for Spielberg on the original "Jurassic Park," and their disagreement manifested into bloody mayhem on-screen.

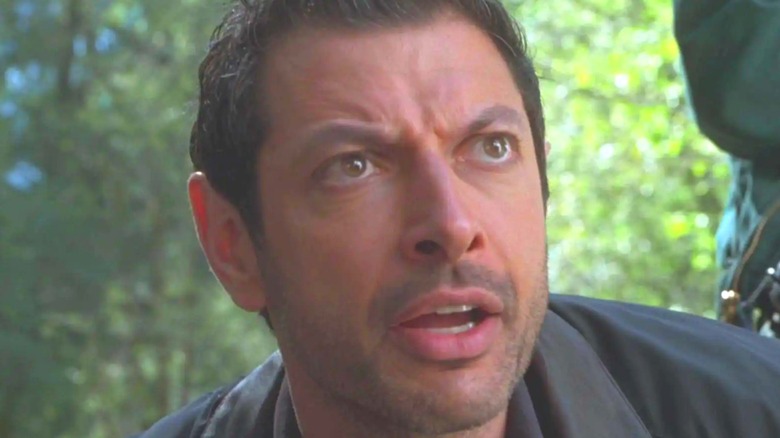

A character in "The Lost World: Jurassic Park," bearded dino expert Dr. Robert Burke, was based directly on Dr. Bakker. Burke hides behind a waterfall when fleeing from a Tyrannosaur. But when he gets scared by a snake, Burke slips and the hungry T. Rex pulls him out of the waterfall, rips off his arm, and polishes off the screaming doctor in a gush of blood. The whole scene was instigated by Jack Horner as a friendly dig at his colleague Dr. Bakker. Spielberg added the character of Dr. Burke, and his death scene, as a favor to Horner (via Empire).

When Dr. Bakker watched the film, he immediately recognized himself in Burke and clearly took the scene in the friendly spirit it was intended, saying, "I told you Rex was a predator!"