How The Wizard Of Oz Is Actually Much Different Than The Book

Today, it seems like any movie adaptation of a popular intellectual property comes saddled with the inevitable albatross of fan sentiment. From social media to fully-fledged fan campaigns, filmmakers are forced to make a choice between addressing fan ideas (hello, John Krasinski as Reed Richards!) or ignoring it at their own peril.

This kind of fan feedback was likely the last thing on the minds of those who adapted L. Frank Baum's popular children's book "The Wizard of Oz" for the 1939 release that transformed cinema. At the time, Baum's four-decades-old novel was a beloved classic — but nevertheless, the film's director(s) and writers (many of which were uncredited) were not shy about transforming the tale.

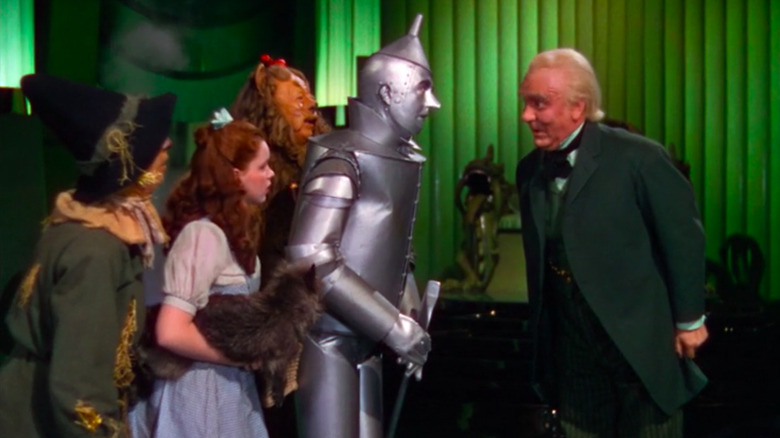

The basic elements are the same: A girl from Kansas is transported via cyclone to a strange land where there are good and wicked witches, a brain-coveting scarecrow, a tin woodman determined to acquire a heart, a cowardly lion desperate for courage, and an all-powerful wizard whose reputation precedes him. However, the details — including the timeline, the addition of several characters, and the adventures of Dorothy Gale (Judy Garland) were changed significantly from the book.

The end result? Although both the book and movie remain iconic works, they exist as very different experiences. Below, a breakdown of the key areas where they diverge.

Dorothy's age is inconsistent

Both the book and movie of "The Wizard of Oz" contain plenty of vivid imagery. There are beautiful landscapes, vibrant colors, and unique characters described or seen in both versions of the story. Even the flat gray of Dorothy's Kansas home is strikingly evocative. But there's one detail neither the book nor the movie mention: Dorothy's age. While Baum's intention in failing to divulge her age may have been to ensure any young reader could see themselves in her, he still includes some hints, such as frequently referring to Dorothy as a "little girl." Plus, the illustrations by W.W. Denslow that accompanied the book when it was initially published make Dorothy look very young. Based on that, it's safe to assume that Baum intended Dorothy to be a prepubescent child.

In contrast, Judy Garland was 16 when she played Dorothy in the movie, and even though efforts were made to make her seem younger (including designing youthful costumes and having the character behave in innocent and immature ways) she still looked like a girl well into adolescence. As a result, while the 1939 film seems to want viewers to see Dorothy as a youngster, Garland's enduring image frequently conveys a petulant teen, not an immature child.

The movie includes several characters in Kansas that aren't in the book

Outside of the brief first chapter and (even briefer) final chapter, the "Wizard of Oz" book barely spends any time in Kansas. Baum dedicated the bare minimum of words to establishing the bleak lives of Uncle Henry and Aunt Em, explaining how the antics of Dorothy's dog Toto helped protect her from the impact of their depressing existence. The movie, on the other hand, puts greater emphasis on Dorothy's life before the twister carries her, Toto, and her house away to Oz — introducing the actors and characters who will soon mirror themselves in this visual medium — and it also introduces several characters who aren't in the book.

The film opens with nearly 20 minutes of its hour and forty minutes in Kansas, using that time to establish Dorothy's positive relationships with Aunt Em (Clara Blandick) and Uncle Henry (Charley Grapewin), as well as farmhands Hunk (Ray Bolger), Zeke (Bert Lahr), and Hickory (Jack Haley), the dreadful Miss Gulch (Margaret Hamilton) and huckster fortune teller Professor Marvel (Frank Morgan). With all this additional time spent establishing Dorothy's backstory, when she gets to Oz, the audience has an easier time understanding those who love her and the sentiment that there's "no place like home."

In the book, the Good Witch of the North and Glinda are two different people

In both the book and the movie of "The Wizard of Oz," there are two wicked witches — of the East and West, respectively. And in both versions, when Dorothy lands in Oz, she's greeted by a good witch, however the two stories don't agree on who she is. According to the book, it's the nameless Good Witch of the North, but in the movie, it's Glinda (Billie Burke), also designated as the Good Witch of the North. Yet, in the book, Glinda is actually the Good Witch of the South, and Dorothy doesn't meet her until she goes to find her in the concluding chapters.

By combining the two characters, the movie eliminates the need to introduce another character late in the story and ensures Glinda is a reliable force for good throughout. However, this also creates a bit of a plot hole: Glinda gives Dorothy the magical ruby slippers at the beginning of her time in Oz but doesn't reveal they have the power to bring the girl home until she has been through many trials and tribulations, leaving open the question of why Glinda held out on Dorothy for so long. It's like if Obi-Wan handed Luke that lightsaber on Tatooine, but never showed him how to turn it on.

In the book, the Good Witch of the North has no idea what the shoes can do, so it's more understandable that Dorothy only completes her long quest in Oz when she meets Glinda at the end of the book.

In the book, Dorothy doesn't meet the Wicked Witch of the West until much later

In the movie version of "The Wizard of Oz," the Wicked Witch confronts Dorothy almost from the moment she lands in Oz; the only reason she doesn't take the girl out is because Glinda protects her. But the fact that Dorothy's house killed the Wicked Witch of the East and that Glinda then gives Dorothy her ruby slippers and, by extension, the magic they contain, means there are multiple reasons for the remaining Wicked Witch to strike out at the child. In fact, she gets very close to eliminating Dorothy and her friends several times, even before they make it to her castle.

In the book, Dorothy doesn't meet the Wicked Witch until much later. In fact, the only reason she and her friends seek out the witch, who has one eye and lacks the movie Witch's famously green skin, is because the Wizard of Oz demands they kill her in exchange for the various prizes he claims he'll grant them. Plus, the book Witch's power is mostly the result of the influence she has over other creatures. Most of her direct contact with Dorothy involves enslaving the girl and then devising ways to acquire her magical shoes. In the movie, however, the Wicked Witch's magic is a lot more powerful and her agenda quite a bit more deadly, and the personal nature of her vendetta against Dorothy makes her substantially more terrifying.

The movie turns the book's silver shoes into the famed ruby slippers

The ruby slippers that Dorothy wears throughout the movie version of "The Wizard of Oz" are arguably the most famous prop in film history. Yet, they weren't in the book.

While the Wicked Witch of the East sported a pair of magical shoes that are given to Dorothy after her demise, Baum described them as silver shoes. And while Glinda magically places the ruby slippers on Dorothy's feet in the movie, in the book, the Good Witch of the North hands the silver shoes to Dorothy after the Wicked Witch of the East's body literally crumbles away in the sun.

In addition, while the shoes in both the movie and the book are the key to getting Dorothy back to Kansas, the ritual is slightly different. Both require Dorothy to click her heels together three times, but in the book, Dorothy has to specify where she wants to go — "Home to Aunt Em!" — and then take three steps to get there. In the movie, Glinda tells her to utter the far more eloquent words "There's no place like home," while clicking her heels. Either way, once Dorothy's back in Kansas, her special shoes seemingly disappear.

The movie skips the Scarecrow and the Tin Man's origin stories

The movie version of "Oz" is stuffed with memorable songs, including those sung by the Scarecrow (Ray Bolger) and Tin Man (Jack Haley). But the songs don't tell us much about how they came to be, instead emphasizing that the Scarecrow wants a brain and the Tin Man wants a heart. While this establishes their motivations for going with Dorothy to see the Wizard, it eliminates the intriguing backstories Baum described in the book.

The Scarecrow's origin involves him being made by a Munchkin farmer, who then learned he was terrible at scaring crows; the magic that brought him to life is never specified. The Tin Man's origin, meanwhile, is much more horrifying.

The Tin Man was once a regular man who was a professional woodchopper. After becoming engaged to a Munchkin girl, the old woman she lived with asked the Wicked Witch of the East to prevent the marriage. So the Witch enchanted the Tin Man's axe, leading him to cut off his own arms, legs, and head. Each time, his mangles, severed body part was replaced by a tin version — until eventually he was entirely made of tin.

In the process of all this, he lost his heart and no longer cared about the Munchkin girl. That is some rough stuff for a kids' story, so it makes sense that the movie left it out.

The deadly poppy fields are one of several obstacles

In the movie, Dorothy's journey to see the Wizard of Oz is fairly straightforward. Sure, she encounters some adversity: she tangles with some ornery apple trees, dodges a fireball from the Wicked Witch of the West, and is momentarily terrified by the Cowardly Lion. But by far the biggest obstacle she and her friends face is the field of red poppies that the Wicked Witch enchants to put Dorothy to sleep. A counter-spell by Glinda soon eliminates the somnambulant spectacle, however, and the group makes it to their destination relatively unscathed.

Dorothy doesn't have nearly as easy a time in the book. After the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion join her quest, the group has to chop down a tree to make it across a vast ditch, even as they're charged by a pair of Kalidahs, vicious animals with the head of a tiger and the body of a bear, They then have to build a raft to make it across a wide river, where the current causes them to drift far away from the yellow brick road, forcing them to walk miles back along the river's edge once they make it to the other side. The quartet also encounters a sleep-inducing field of poppies — but it's not due to an enchantment. Instead, it's a natural property of the flowers, another of the many ways the book's version of Oz is more dangerous than what we see in the movie.

The Emerald City and the Wizard are presented differently

Dorothy and her friends make it to the Emerald City in both the book and the movie, but their experiences there aren't nearly the same. In the film classic, the group has trouble entering the city and are scolded by the Guardian of the Gate for ringing the out-of-order doorbell. In the book, the group easily gains entrance, but instead of being let in immediately, they are taken to a room where the Guardian of the Gate fits them with green-tinted glasses that they aren't allowed to take off as long as they're in the city.

In both the book and the movie, the Emerald City is impressive; one of the most eye-catching images in the film, however, is only in the latter.

The Horse of a Different Color, a horse who regularly changes color, is one of the more whimsical, unforgettable special effects in the film (and particularly innovative for its time); the horse is also completely unique to the movie. Meanwhile, the group spends several days in the Emerald City in the book and each of them sees the Wizard separately. In the film, the Wizard appears as the hologram of a giant head; the Wizard changes appearances in the book, with each member of the quartet seeing a different version of him, from a giant head to an attractive woman to a huge beast and even a ball of fire.

The book includes a lot more talking animals

The Cowardly Lion plays a major role in both the book and movie of "The Wizard of Oz," although in the book, he's just an ordinary lion who happens to possess the power of speech, rather than the anthropomorphic kind who can walk on two legs. Also in the book, Dorothy and her friends meet many more talking animals than the Lion. Before they get to the Emerald City, they encounter a kindly talking Stork who helps them rescue the Scarecrow from the river and a group of field mice, who help them rescue the Cowardly Lion from the field of poppies after the Tin Man saves their queen from a wildcat.

Meanwhile, when the group goes to find the Wicked Witch of the West, she sends a pack of talking wolves and then a murder of talking crows after them, as well as a swarm of bees that don't talk but buzz loudly. When that fails, she sends the flying monkeys. Although the flying monkeys are also seen in the movie, in the book not only do the monkeys talk, they're also not the Witch's henchmen but at the mercy of a charm that forces them to obey the Witch's commands because she possesses an enchanted Golden Cap. If that weren't enough, after the group defeats the Witch, they find themselves in a forest where they encounter a meeting of all sorts of talking animals.

The movie changes how the Wizard grants wishes

Adults and savvy children who read the book or watch the movie of "The Wizard of Oz" will understand that the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion already possess the things they want the Wizard to give them. This is something the Wizard knows too — so in both versions, he grants the trio's wishes in superficial ways that imbue them with the belief that they have the attributes they covet. However, the items he chooses to give them to accomplish this are different.

In the movie, the items are all external. To prove the Scarecrow has a brain, the Wizard gives him a diploma; to prove the Tin Man has a heart, he gives him a ticking heart-shaped trinket; and to prove the Cowardly Lion has courage, he gives him a medal with "courage" engraved on it. In the book, the items are all internal. The Scarecrow's brains are a mixture of bran, pins, and needles that the Wizard stuffs into his head, the Tin Man's heart is silk cut into a heart shape that he places inside his chest by cutting out a piece of tin, and the Cowardly Lion's courage is a potion the Wizard tells the beast to drink. Given the complications of taking off real actors' heads and carving holes in their chests, the movie's decision to adjust this part of the book while retaining its basic meaning makes a lot of sense.

Dorothy explores much more of Oz in the book

In the "Wizard of Oz" film, Dorothy's journey to the Emerald City is fairly efficient; even with her side trip to melt the Wicked Witch, she's only in Oz for a few days. In the book, however, Dorothy spends significantly more time in the magical realm, exploring more comprehensively. This is especially true in the final chapters of the book, when the group seeks out Glinda.

The journey on the page is filled with new adventures for Dorothy and her friends. They find themselves in a land of people and structures made of fragile china; they travel through a forest where the Cowardly Lion uses his newfound courage to defeat a giant spider; they traverse a rocky hill guarded by men who knock the travelers off the path with their flat heads; in the South, they see the Quadling country Glinda rules over, defined by people and buildings adorned in red.

In fact, one of the most striking things in the book is the way Baum color codes the various lands of Oz. In both the book and movie, the Emerald City is green, but in the book, the other lands adhere to a specific color as well. In addition to the Quadlings' red, the Munchkins favor blue, and the Winkies in the land of the Wicked Witch of the West love yellow.

By the end of the book, the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion each have their own kingdoms

Before the Wizard of Oz flies off in a hot air balloon in the book and movie, he leaves the Scarecrow in charge of the Emerald City. But there is some deviation in the overall assignments.

In the film, the Wizard appoints the Tin Man and Cowardly Lion as the Scarecrow's assistants. In the book, he explains that ruling a kingdom isn't a group activity. Instead, the Tin Man and Cowardly Lion have plans to lead kingdoms of their own after Dorothy leaves. The Tin Man confesses that the Winkies asked him to take over as ruler in the West after Dorothy killed the Wicked Witch, a position he plans to fill.

Before killing the giant spider that was menacing the forest animals the group encountered while traveling to see Glinda, the Cowardly Lion secured a promise that he would be appointed king if he rid the animals of their problem. While the movie alludes to the Cowardly Lion's ambition in the song "If I Were King of the Forest," in the book his desire for a kingdom comes to fruition, as does his desire to return to the Forest — the place the book's Cowardly Lion indicates he's most comfortable.

The movie and book disagree about whether Dorothy's adventure is real

Perhaps one of the most noteworthy changes in the "Wizard of Oz" movie is the question of whether Oz and Dorothy's adventure really occurred. In the book, Baum confirms that everything in both Oz and Kansas are absolutely real. This is made clear by the fact that Uncle Henry has to build a new house to replace the one the twister blew to Oz.

In the movie, Dorothy wakes up in her bed in Kansas with her aunt and uncle worrying over her, suggesting that she hit her head during the cyclone and her time in Oz was just a very elaborate dream. To make it even more obvious that Oz was pure fantasy, Dorothy soon realizes that all the characters in her life in Kansas outside of Uncle Henry and Aunt Em were also in Oz, even as Dorothy insists the place is real. And the movie further emphasizes that it was all a dream by only crediting the actors who played characters in Kansas and Oz by the names of their characters in Kansas, leaving it up to a sharp-eyed audience (who, don't forget, couldn't freeze-frame anything in 1939) to realize that the three farmhands are the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion, Miss Gulch is the Wicked Witch of the West, and Professor Marvel is the Wizard.

The most famous lines from the Wizard of Oz don't appear in the book

"The Wizard of Oz" includes some of the most recognizable lines in film history. From "I've a feeling we're not in Kansas anymore" to "I'll get you my pretty ... and your little dog too!" and from "Lions and tigers and bears, oh my!" to "There's no place like home," these lines have been quoted over and over again.

Even people who haven't seen the movie know "The Wizard of Oz" is the source of these quotes. Yet, people might be surprised to learn that these famous words weren't composed by L. Frank Baum, but by the writers responsible for the movie's screenplay: Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, and Edgar Allan Woolf (along with more than a dozen uncredited writers).

While there are several places where the movie briefly quotes the book directly, most of the dialogue (and all of the songs) were composed specifically for the film. So while the book of "The Wizard of Oz" remains a classic, the movie has made its own significant and separate cultural impact. This is also true of some of the design elements of the film, including the Witch's green skin and Dorothy's ruby slippers, now more closely associated with "The Wizard of Oz" in many people's minds than the one-eyed Witch and silver shoes that Baum specified in the book.