The Ending Of True Grit Explained

Joel and Ethan Coen's 2010 film "True Grit" would seem to be one of the celebrated indie duo's more straight-forward films. Based on Charles Portis' Western novel, the story of young Mattie Ross and her quest for vengeance against the man who killed her father had been told on screen once before in 1969. That well-remembered version stars Kim Darby as Mattie and John Wayne in his Oscar-winning role as Rooster Cogburn, the ornery, one-eyed U.S. Marshal she hires to track the killer. To tackle this remake, the Coens enlisted some ringers (and several future Marvel Cinematic Universe stars), including Hailee Steinfeld as Mattie (in a breakthrough Oscar-nominated performance), the Dude himself, Jeff Bridges, as Cogburn, and Josh Brolin, star of the Coens' Oscar-winning neo-western "No Country for Old Men," as the murderous Tom Chaney.

While the film is darker and grittier than the John Wayne version, its differences mostly come from being a more faithful adaptation of Portis' novel, which centers its narrative around Mattie rather than Rooster. Her quest to apprehend Tom Chaney is both a literal and spiritual trek through the wilderness; in many ways "True Grit" is as much of a religious film as the Coens' previous effort, 2009's "A Serious Man." Its themes of violence and retribution come together in an ending that favors Mattie's journey over plot mechanics, which might leave viewers with some unanswered questions. Here is the ending of "True Grit," explained.

Mattie and the cave

The film's climax finds Rooster single-handedly charging Lucky Ned Pepper (Barry Pepper) and his gang on horseback while Mattie holds Tom Chaney at gunpoint with her father's pistol atop a mountain. She fires, killing Chaney, but the force of the recoil sends Mattie flying into a narrow cave tucked into the side of the mountain. Trapped, she calls for help, while a nest of rattlesnakes pours out of the chest cavity of a nearby skeleton. Rooster and the effete Texas Ranger LaBoeuf (Matt Damon) come to her rescue, but not before a rattlesnake bites her hand.

Taken at face value, it's a terrific action sequence that neatly ties up Mattie's pursuit of Chaney. But the scene also works on a metaphorical level as a rebirth of sorts for Mattie, who until now has seen herself apart from the worldly, violent likes of Rooster and LaBoeuf. Now, having taken a life herself, she is plunged into darkness and infected by a poison that slithers out from a dead man's heart. She's pulled from the cave and rescued, but not without leaving a piece of herself behind — the girl who fell into the cave is someone different than the one who came out.

Rattlesnake treatment

When Rooster sees the snake bite on Mattie's hand, he uses his knife to make an X-shaped incision around the fang marks and sucks out the poison. He puts her on her pony, Lil' Blackie, and makes a desperate ride through the night to reach civilization, or at least close enough for Mattie to get proper treatment, as rattlesnake venom can be fatal if left untreated.

The film is correct about the danger of rattlesnake bites as well as their symptoms, and Rooster is right to ride as fast as he possibly can. Untreated bites can cause irreversible organ damage within hours and death within days. Rooster's treatment methods are accurate to the period, and actually fairly tame and common sense compared to some wilder remedies from that era, though modern advice discourages both cutting the wound and attempting to suck the poison out, recommending keeping the afflicted area immobilized and underneath the heart as the most effective way to halt the spread of venom.

Lil' Blackie

During that midnight ride, Rooster pushes Lil' Blackie too hard, and the pony collapses in distress. Rooster puts the animal out of its misery with a bullet to the head while Mattie cries out in anguish. It's a shocking scene, not just because of the explicit (though safely staged) violence against an animal, but because it shows a different facet to Rooster's nurturing side; he's willing to ride a horse to death to save Mattie, and put it down rather than let it suffer. Then he takes Mattie in his arms and runs the rest of the way, finally the father figure he was destined to be from the start, guiding a child through the dark.

The death of Lil' Blackie also serves the film's theme of Mattie's coming of age. The scene in which she acquires the pony is one of "True Grit's" more comedic moments, as she talks circles around the livery owner Col. Stonehill (Dakin Matthews), negotiating first a refund of $300 for three ponies that her father bought before his death, and then a sale of $10 to buy one of them back. It's a delightful early scene, showcasing not only Steinfeld's excellence in the role, but also Mattie' precociousness. She speaks with the confidence of an adult, but she is still a child, evident when she gives the pony an obvious name with two different diminutives. His death represents her putting away childish things.

Old Maid Mattie

Fans of the John Wayne version of "True Grit" may be most surprised by the inclusion of an epilogue set 25 years after the events of the rest of the film. After Rooster manages to run Mattie to safety, a fade to black takes us to the year 1903, just over a quarter-century later, with an adult Mattie now played by actress Elizabeth Marvel, whose voice we heard at the start of the film. After losing contact with Rooster for many years, she receives an invitation to meet him in Memphis, where he will be performing in a Wild West stunt show alongside former cowboy outlaws Cole Younger and Frank James.

In her narration, Mattie describes herself as an "old maid," with a reputation for being eccentric. The most striking thing about her now, however, is that she is an amputee. Her life was saved after the snakebite, but not her arm, which was removed up to the elbow, an effect captured on film with a combination of digital effects and an amputee stand-in for Marvel. The missing arm is symbolic of the toll that her vengeance took, a spiritual wound made flesh, but more interestingly, it marks her as kin to the one-eyed Rooster — both surrogate father and surrogate daughter have had the world take pieces of them away.

The Younger-James Show

Rooster Cogburn and Mattie Ross are fictional characters, but Cole Younger and Frank James were very real, and they did indeed operate a Wild West show for a brief time in 1903, long after the death of their infamous gang leader, Jesse James. The Younger-James gang's exploits have been depicted on film many times, from Walter Hill's "The Long Riders" to Andrew Dominik's "The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford." As the American frontier era came to a close at the end of the 19th century, many famous Western figures took advantage of audiences' newfound nostalgia for the cowboy days by forming touring companies and stage shows (most notably "Buffalo" Bill Cody, who began his famous Wild West show in 1883).

When Mattie journeys to the Memphis fairgrounds to reunite with Rooster, she is met by Younger (Don Pirl) and James (James Brolin in an uncredited cameo). Unfortunately, the two aged outlaws have bad news for her: Rooster died while they were on tour in Arkansas, and was buried there. Mattie thanks Younger, who stood up to greet her, for the information; she looks James, who remained seated, up and down and remarks, "Keep your seat, trash."

Confederate graveyard

In the fairgrounds scene, Younger informs Mattie that Rooster died of a condition he referred to as "night hoss." This is, as far as any record shows, not an era-specific term used to describe any known affliction, and appears to be an invention of Portis' novel. It may be referring to a nighttime restlessness brought on by alcohol, which would certainly make sense for Rooster, but the "night hoss" might also refer to Lil' Blackie and some lingering illness brought on from the night he saved Mattie's life.

Younger also mentions that Rooster was buried at the Confederate graveyard in Jonesboro, Arkansas. This bit of dialogue confirms what was implied in an earlier scene when Rooster and LaBeouf argue over what each did during the Civil War. Rooster was indeed a Confederate soldier, and one who rode, alongside Younger, with the guerilla battalion of William Quantrill. While the federal government founded national cemeteries for the burial of Union soldiers not long after the Civil War, for decades the burial of Confederate soldiers fell to local governments, women's groups, and veterans' associations. While acts of Congress allowed for the marking of Confederate graves and the construction of a Confederate monument at Arlington National Cemetery at the turn of the century, it wouldn't be until 1914 that Confederate soldiers were allowed to be buried at national cemeteries in the South.

Rooster's coffin

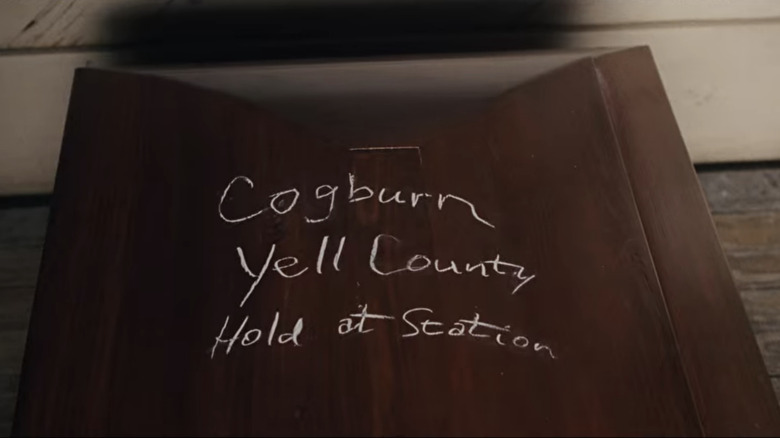

But Mattie, ever head-strong and accustomed to getting her own way, will not abide Rooster laying to rest in some Civil War cemetery. She orders his coffin exhumed and shipped to her home in Yell County, Arkansas, where he is re-interred alongside her father in the family plot. His new gravestone dryly refers to him as "a resolute officer of Parker's court," which is the context in which Mattie first knew him. Much like a child who only knows a parent through their own experience, for Mattie, Rooster is nothing but the man he was in those few days they spent together. None of his life before or after her is even worth remembering.

The sequence of Rooster's reburial shows his coffin being loaded onto a railcar with its destination written in chalk. If that moment strikes viewers as familiar, it is because the Coens used a nearly identical shot at the start of the film, when the body inside the coffin was that of Mattie's father. By repeating the shot here, the Coens underline Rooster's importance to Mattie, and the way she forced him, at times against his will, into a fatherly role.

Wither LaBeouf?

In the Coen Brothers' "No Country for Old Men," a major character is killed offscreen. In "Fargo," a secondary character (who is nonetheless important to the plot) is killed offscreen. It isn't that the Coens are trying to mess with the audience (well, maybe a little bit), so much as that the plot and narrative elements that they prioritize are not always those an audience might expect. In "True Grit," much is made of Mattie's quest to bring Tom Chaney to justice — specifically, justice in Arkansas for the murder of her father. The problem is that Chaney is also wanted in Texas, and at a substantial reward, for a different crime, which is where Matt Damon's Ranger LaBoeuf comes in. Mattie is adamant that Chaney face trial in Arkansas, while LaBoeuf is likewise adamant that he will be extradited to Texas, and Rooster feels that justice is justice no matter where it happens.

This is a significant sticking point for Mattie and a question to be answered by the film ... until it isn't. After he and Rooster rescue Mattie from the cave, LaBoeuf is never seen again. Grown Mattie even notes in her narration that she doesn't know if LaBoeuf is alive or dead. Presumably he took Chaney's body back to Texas to claim his reward, but we'll never know for sure. At the end of the day, the resolution of this plot point was not as important to the Coens as Mattie's spiritual journey.

Leaning on the everlasting arms

Mattie's dialogue, especially at the start of the film, is littered with Christian allusions and turns of phrase. It's a vision of the world that the rest of the film both rebuts in the form of a lawless wilderness ruled by violence and confirms in Mattie's survival of that wilderness and that violence. The Coens are experts at infusing their films with irony and sincerity at the same time — often in the same scene. One of their best tricks for maintaining this balance in "True Grit" is through Carter Burwell's orchestral score, which adapts a number of Christian hymns that would have been new and popular at the time of the film.

Burwell makes excellent use of E.A. Hoffman and A.J. Showalter's composition "Leaning on the Everlasting Arms," which serves as Mattie's unofficial theme song. It pops up throughout the film, most notably in the scene when Mattie and Lil' Blackie ford a rushing river to catch up with Rooster and LaBoeuf, and at the film's end, when Mattie leaves Rooster's grave to the sounds of Americana singer Iris DeMent's 2004 recording. The song's lyrics, inspired by a passage in the book of Deuteronomy, describes God's grace as a pair of arms keeping the singer safe and protected through life. Mattie loses that feeling of security when her father is killed and finds it again in Rooster Cogburn, but more importantly, the epilogue shows us that she has found that strength in herself.