The Ending Of The Life Before Her Eyes Explained

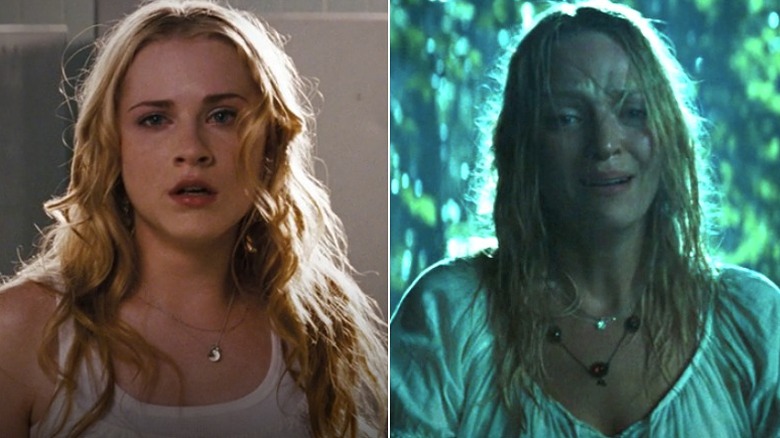

Vadim Perelman's "The Life Before her Eyes," which hit theaters in 2007, explores the complicated dance of trauma and mundane life. It also places specific focus on female relationships, especially the fears, struggles, joys, and dilemmas particular to teenage girls. The film accomplishes this by exploring two distinct stories, both belonging to the same woman: We follow teenage and adult Diana Adams (Evan Rachel Wood and Uma Thurman respectively) as she moves through life. Given the film's not-necessarily surprising twist ending, this back-and-forth approach makes sense.

So, what exactly is the ending of "The Life Before Her Eyes" — and what does it mean? Essentially, teenage Diana survives a school shooting at the age of 17, not long after making the decision to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. We meet adult Diana on the 15th anniversary of the event, and aside from her understandable preoccupation with memories of that day, her life seems pretty idyllic: she's married to the college professor she had a crush on in high school, teaches art history at a local college, and has a precocious, unrealistically darling nine-year-old daughter named Emma (Gabrielle Brennan).

Despite all she went through in her teens, it appears Diana's life has turned out well. Of course, all is not well, and not everything is as it appears — on multiple levels.

The Life Before Her Eyes' twist isn't intended as such

Evan Rachel Wood's Diana is your archetypal rebellious teenager: she smokes, she has sex, she acts out without fully understanding why — she even, at one point, becomes pregnant by her much older boyfriend (played by pre-superstardom Oscar Isaac), and struggles both with her decision to terminate the pregnancy and with the effect it has on her body.

Uma Thurman's reserved, nervous, and maternal Diana bears little resemblance to her teenage self, ostensibly in response to all she went through in her youth. Over time, we see a number of cracks begin to form in Diana's idyllic adult life. Her own daughter begins acting out, her husband may or may not be having an affair, and with the memorial of the shooting coming up, she's more and more overwhelmed by her survivor's guilt.

We learn that during the shooting, the gunman cornered Diana and her friend in the girls' bathroom, and asked the teens to choose which one of them would get to live. It's assumed that Diana's friend sacrificed herself, but the film eventually reveals that although Diana's friend did initially step up, it is Diana who dies after volunteering to be shot.

The film ends on a twist, but not one the audience isn't meant to see coming. On the contrary, the narrative goes out of its way to force viewers to question what they're accepting as the present-day, and it does so with an eye toward reiterating its ultimate theme.

Duality is its own character in The Life Before her Eyes

Vadim Perelman's use of duality in the film ranges from subtle to intentionally heavy-handed, and goes a long way toward queuing the viewer in to what's really going on. In addition to its dual structure, the film sets up its characters and events in contradictory pairs. Teenage Diana's best friend Maureen (Eva Amurri), for instance, is god-loving, academically-minded, and cautious.

The friends represent the age-old, binary depiction of women in literature and film — a point they themselves make, in case the audience missed it. "The virgin and the whore," Maureen says at one point — "this fall on the WB." In a sense, this is the story's way of telling us that Diana couldn't possibly have been the one to survive: the "whore," as we all know, must be punished for her sins. Furthermore, Diana's traumatic experience undergoing an abortion is contrasted with her experience in the school bathroom. In the former, she must decide whether or not she's ready to create a life; in the latter, she must decide whether or not she's ready to forfeit her own.

The film's repeated references to reality and imagination are another means by which Perelman foreshadows his reveal. In adult Diana's lecture on Gauguin's "Vision of the Sermon," she says the artist "doesn't believe in any demarcation between the real and the imagined," while teenage Diana's conversations about God with her churchgoing friend often revolve around the difference between what's real and what our mind convinces us is real.

In Perelman's film, the answer is in the title

When Diana first falls for the professor we're meant to believe she ultimately marries (Paul, portrayed by Brett Cullen), it's during a lecture he's giving on the ability to "author our own destinies." In the lecture, which acts as a summarization of the film's twist, Paul instructs his audience to "begin to be now what [they] will be hereafter" by having the courage to imagine their future, and pick out the life they want from "all the possible lives that pass before [their] eyes."

This, of course, is exactly what Diana does in the suspended time between when she is shot and when she ultimately dies. Everything we see and are meant to understand as the "present" occurs only in her imagination, in that third interval of existence between life and death, when she sees her life — not as it was, but as it might have been — flash "before her eyes."

Paul's speech is far from the director's only overt nod to his later reveal. Throughout the film, we repeatedly hear The Zombies' "She's Not There" (because she's not, really), and in the imagined present, Diana's daughter Emma's behavior — "you hate me," she tells her mother out of the blue at one point — can be read as the behavior of a child that was never actually born. Finally, prior to Diana's death, she sees the name Emma on a cross put out by the church to "represent the unborn."

The Life Before Her Eyes offers some hope

While all this foreshadowing and technique may be the film's way of exploring the mind plot-wise, there's something else going on here with regard to the film's exploration of time and trauma.

"The Life Before Her Eyes" reminds audiences that unlike tragedy, trauma interacts differently with time. The trauma survivor who believes an otherwise benign sound or flash of light to be something it isn't, doesn't feel as though they're "imagining" something, because the triggering incident puts them back in the time and space of the actual trauma. The line between what's real and what's imagined isn't simply blurred by the mind's involuntary response to a given catalyst, but erased entirely, its very existence called into question.

In Vadim Perelman's film, this erasure is explored from the opposite perspective. Rather than a present-day survivor being forced back in time to relive a traumatic event, a past casualty projects herself into the future, imagining an entire life for herself that's every bit as real to her as her memories of the event would be had she lived. Though the film doesn't attempt to present the reality of Diana's death as any kind of happy ending, there is some optimism in its presentation of the mind — which Paul refers to as "the voice of God and the nature and heart of man" — as a living entity unto itself; an existence overflowing with a potential for hope and happiness, so often missing in what we understand and experience as "reality."