The Tragedy Of Macbeth Review: Fair Is Foul, And Foul Is Fair

The plays of William Shakespeare have been adapted so many times throughout pop culture history that you could be completely ignorant of them while still immediately familiar with their basic narrative details. "King Lear" has been reimagined in everything from "The Lion King" to "Succession," teen comedies ranging from "10 Things I Hate About You" to "She's the Man" have lifted from his lighter works, and if you go to your local movie theater now, you'll probably be able to grab tickets to a screening of a musical more than a little indebted to Romeo and Juliet (if Spider-Man hasn't already taken over the entire multiplex, of course). His plays have been adapted and recontextualized so many times that, on the screen at least, a direct, faithful retelling of one of his most famous works is often the exception, rather than the rule.

The works of the Bard have long been echoed in the films of Joel and Ethan Coen, albeit far less pronounced than their weightier literary influences, from Homer's Odyssey (in both "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" and "Inside Llewyn Davis") to dense biblical texts (The Book of Job in "A Serious Man"). This oversight in critical analysis of their work is largely because the Shakespearean text that most informs their work is "A Comedy of Errors," one of his earliest and least essential plays — but its central narrative framing of chaos following mistaken identity can be found pushed to madcap extremes in "Burn After Reading" and straight into the wood chipper in "Fargo." Their grizzlier crime films may have invited comparison to his merciless tragedies, but their sensibility largely remains rooted in this core comic convention.

The ultimate Coenesque tragedy?

Despite this, no Shakespearean quote quite defines the brothers' work quite like that immortal phrase uttered by Macbeth in a despairing monologue following Lady Macbeth's passing, his eulogy stating that life "is a tale told by an idiot, signifying nothing." The Coens' films have a clear moral compass; their close friend and early collaborator Sam Raimi joked that in their films, innocent people must suffer and the guilty must be punished, no matter how deceptively light the comic tone. The punishment Macbeth initially receives is the realization that his power grab has left an existential crisis — and, knowing that it wasn't broke so he doesn't try to fix it, Joel Coen (working without his brother Ethan for the first time) doesn't add a new spin on the text, largely because this ideology best describes the bleak worldview of many of his best character studies. This is already one of the most unsparing of Shakespeare's works, and on paper, it's a perfect marriage of director and material.

"The Tragedy of Macbeth" is, unfortunately, a triumph merely in its bold aesthetic choices, blurring the lines between stage and screen with a production design that looks at once confined and otherworldly. The Scottish Play has been adapted regularly in the movies, with this ranking as the 46th major retelling, standing alongside 44 other Macbeths in the shadow of Akira Kurosawa's still unparalleled "Throne of Blood." This is partially why it feels like such a disappointment; that even when brought to the screen by one of the great American filmmakers, and two of Hollywood's most reliable actors, the end result remains laboriously faithful to the text. Coen's career-long reverence for Shakespeare may have come full circle, but it has done so in a way that sacrifices his personality as a writer. The only surprise here is the striking staging, which aims to reimagine the boundaries of the text while the screenplay settles for simply rehashing it.

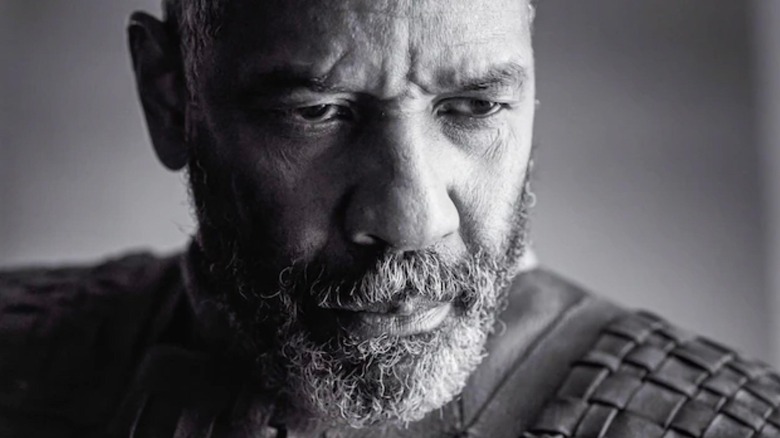

The story is the same as it ever was; Macbeth (Denzel Washington) is a Scottish lord, faithful to King Duncan (Brendan Gleeson). After being met by three witches (an unnerving Kathryn Hunter), he is told that the path to the throne is all his — alongside his wife, Lady Macbeth (Frances McDormand), he conspires to kill the king and seize power. But once there, he finds that it isn't all its cracked up to be, and his paranoia quickly turns both violent and delusional.

Blurring stage and screen

Despite offering Denzel Washington the rare opportunity to flex his Shakespeare-trained chops, his first starring role in a cinematic adaptation since Kenneth Branagh's 1993's "Much Ado About Nothing," I was left with very little to remark upon about either performance. Macbeth is so ingrained within the cultural consciousness, it's now far easier to detect and analyze a bad portrayal of its characters than a good one; instead of being impressed, I resigned myself to thinking that Washington and McDormand merely rose to the occasion. These are two of the most famous characters in English literature, and this overfamiliarity may have been a significant factor in my muted enthusiasm — they're certainly the best actors to have ever played these roles onscreen, but they never transcend the straightforwardness of the adapted screenplay.

Far better is the scene-stealing appearance by Kathryn Hunter, who plays all three of the witches with a genuine menace. Earlier adaptations, most notably Roman Polanski's 1970s take and the 2015 Michael Fassbender-led adaptation, have leaned into the gothic horror inherent in the story's supernatural aspects, but Coen and Hunter push this to its logical extreme. Here, distorted sound design helps give credence to the idea that the witches are a threat not of this world, as much as their ability to transform into crows. Coen's filmography isn't light on truly horrific moments, but this is the most he's leaned into genuine horror territory, offering something startling within a retelling that otherwise just feels like homework; handsomely told, but inescapably boring due to how many times we've heard this before, and how little else it offers in the way of innovation.

"The Tragedy of Macbeth" was filmed entirely on sound stages, a move designed by cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel as making the film look "untethered from reality." This bold artistic choice surprisingly proves to be the one aspect commanding attention, the film staying within the restrictions of a theatre stage and yet offering glimpses to a world beyond — the vast Scottish moors, and the desolate lands where the Witches reside. It calls to mind Lars Von Trier's film "Dogville," a Depression-era gangster film taking place entirely on deliberately fake sets in a Copenhagen film studio, and ultimately has the same problem (even if Von Trier's film is far more successful). As much as it enraptures due to this creative choice, it never stops being distracting, leaving the impression that we are merely watching a director try out a technical exercise. When viewed in tandem with the slim reconfigurations of the source material at hand, it became impossible to view this in any other light.

It may have been championed as a bold triumph by dedicated students of the Bard, but for those of us who haven't studied Macbeth since high school, there's very little here that feels groundbreaking, with nothing inspired to add to the material beyond staging arrangements. There are bold aesthetic choices that command attention — but when these offer more food for thought than Shakespeare's prose, then it's clear the real tragedy of this Macbeth is just how disappointing it is.