The Ending Of The Power Of The Dog Explained

"The Power of the Dog" is now available in limited theatrical release and premieres on Netflix on December 1.

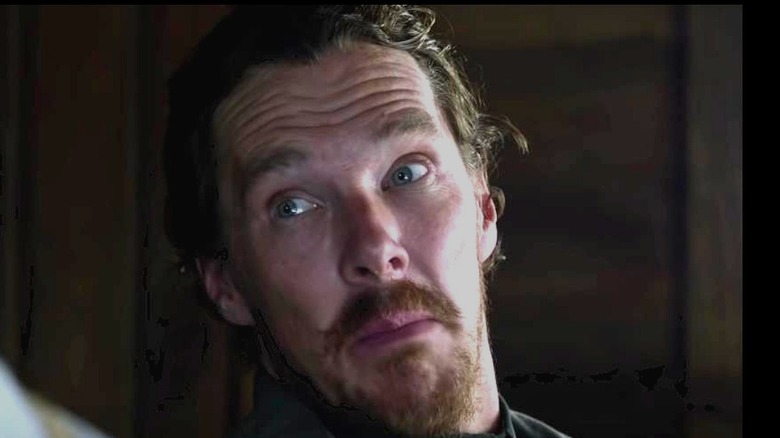

In Netflix's "The Power of the Dog," the Oscar-winning director Jane Campion ("The Piano," "In the Cut") turns her camera and commentary on the viewer in a masterful, powerful cinematic sleight of hand. The film — Campion's first since 2009's "Bright Star" — is adapted for the screen by the director from Thomas Savage's 1967 novel of the same name (via Goodreads). Starring Benedict Cumberbatch, Kirstin Dunst, Jesse Plemons, and Kodi Smit-McPhee, this upcoming Netflix Western is set in early 20th century Montana and follows brutish, menacing "manly man" cattle rancher Phil Burbank (Cumberbatch) as he psychologically terrorizes his brother George (Plemons), George's wife, Rose (Dunst), and her son, Peter (Smit-McPhee).

"The Power of the Dog" unfolds in a series of five chapters whose story is told chronologically and whose tension builds then releases itself — slowly, though not reassuringly — as the audience learns more about the psychology and motivations of each character. On the surface, Campion's latest is a film about the horrors of toxic masculinity, and what it means to "be a man" in a buttoned-up, old-fashioned society that forces individuals to fight, hide, and repress their sexuality. In its final reveal, however, this movie proves it has just as much to say about our contemporary beliefs and interpretations as it does about those we believe we've moved past.

The Power of the Dog is a simple set-up with a complex theme

The premise of "The Power of the Dog" is relatively simple, but it exists in stark contrast to the film's complex themes and subtext. The verbally abusive Phil attempts to tighten (indeed, succeeds in tightening) his control on his small universe and the people around him when George marries the widowed Rose and moves her into the brothers' shared home.

We learn early on that Phil cares about no one in the world save himself and his long-deceased cowboy mentor, a man named Bronco Henry. Prior to becoming a rancher, Phil studied Classics at Yale. As a result, a not-unsubtle element of his macho personality is his repeated mispronunciation of words he deems too fancy or delicate. (Because real men — while they may be street smart, rational, and pragmatic — are not intellectuals.) The weak-willed and beaten-down George is unable to protect his new wife from Phil's unceasing ire. When her son, Peter, joins them on the ranch, the audience fears as much for Peter's safety as it does for Rose's.

That's because, unlike Phil, Peter is gentle, methodic, empathetic, sensitive, and wholly uninterested in the gritty, aggressive, and hyper "masculine" identity in which the men around him — and Phil, in particular — wrap themselves. For a majority of "The Power of the Dog," Phil's cruelty and desperate domination of those around him is its own all-powerful and all-encompassing entity and one that puts the fear of God in both Rose and the audience.

Toxic masculinity looms large in The Power of the Dog

In "The Power of the Dog," toxic masculinity is as much a character as the people in the frame. Embodied by the hyper-macho, abusive, and self-satisfying Phil, it lurks around the tension-filled home and hovers over everyone and everything. Even Phil's footsteps are heavy with menacing intent. They don't just echo — they boom, crack, and reverberate like thunder. Constantly braced for a storm that's ever-present and ever visible on the horizon, Kirsten Dunst's anxiety-filled Rose begins to crack as Phil watches her from God-like angles at the top of the stairs or a second-story window. It's revealed that Rose's first husband, Peter's father, drank himself into a psychological breakdown that resulted in his death by suicide. Now Rose, who's teetotal at the film's onset, begins drinking heavily at all hours of the day to soothe her frayed nerves.

When her seemingly fragile son Peter arrives for the summer, the effects of Phil's torture on Rose leave her in a state of fear that reaches a fever pitch. She is rarely, if ever, sober, constantly ill and hungover, and is left a hollowed-out husk of the mother Peter bid adieu just months before. At this point, focused as we are on Peter and Rose's safety (and distracted by the film's claustrophobic unspooling of Hitchcockian terror), it's easy to forget the young man's soft and calculating voiceover at the start of the film — but this is a mistake.

After his father died, all Peter wanted to do was ensure his mother's happiness. "For what kind of man would I be," he asks, "if I didn't save her?" Campion's film revolves around the answer to that question, and Peter never loses sight of it.

Not everyone is as they appear in The Power of the Dog

The viewer slowly becomes aware that Phil's machismo is a defense mechanism, a terrifying mask he uses to conceal his repressed sexuality. Through a progression of poignant scenes, it's revealed that Phil's admiration and reverence for Bronco Henry is linked to his romantic feelings for his mentor. We understand that the two were "more than" friends, a phrase Phil himself uses when describing their relationship to Peter. By now, Phil has begun to take Peter under his wing, molding him in Bronco Henry's image — putting him in boots, teaching him to ride, and, importantly, braiding him a cowhide rope as a gift — all in an attempt to relive his great love.

At no point does the film allow us to root for Phil, but we are given a glimpse into his psychology and motivations. It's almost too easy — and therein lies the film's true magic — to see Peter as a sacrificial lamb wandering to his slaughter. Though it's clear Peter is no longer afraid of Phil (he even mocks him by using his name at the beginning and end of sentences), it still appears as though the Burbank family patriarch is the manipulator and Peter, the manipulated. The young man's demeanor is never anything but cool and calculating. However, his interests and his youth fool us, as well as other characters, into seeing him as "delicate."

But Peter is studying to be a doctor. He kills and dissects animals with objective, studious precision. At one point, he walks through a group of ranchers shouting slurs at him and doesn't flinch. In other words: the film never actually posits Peter is fragile, yet the audience sees him as such, particularly in contrast to Phil. Again, this is a mistake and a sneaky commentary on our contemporary assumptions about (and understanding of) strength and power.

The Power of the Dog is no match for Peter

The ending of "The Power of the Dog" is (and isn't) a twist; we really should have seen it coming, and that's the point. Phil becomes enraged when Rose gives his coveted cowhides away to a Native merchant. His rage comes not from the hides' value but from his fixation on using them to make a rope (a token of love, he thinks) for Peter. Peter appears to save his mother by providing Phil with the hide he'd been saving because, as he tells Phil and as we're foolishly willing to believe, he wants to "be like" him. But the rawhide Peter offers up comes from a diseased cow. The dead animal's illness works its way into an untreated cut on Phil's thumb, and he becomes ill and dies.

That we manage to miss that this was Peter's plan all along is the film's true reveal, and it says more about its contemporary audience than it does about the period in which the film takes place. In one scene, Peter comforts his drunk mother by promising he'll ensure she "doesn't have to do this." We then see him flipping through a medical book. We even hear him comment on Phil's wound and watch as he systematically removes the hide off an obviously diseased cow. But Peter's seeming meekness belies a calculating single-mindedness. Couple this with the fact that society hasn't evolved much in our understanding of masculinity, and we're so concerned for Peter's safety that we fail to see him as the avenging angel that he is.

In Psalm 22 of the Old Testament, King David asks to be saved from the dangers that surround him and pleads for intervention from God: "Deliver my soul from the sword; my darling from the power of the dog" (via Bible Gateway). Peter isn't the film's darling; Rose is, and it's her soft-spoken son — not some looming, all-powerful deity — who delivers her from evil.