The Untold Truth Of Netflix

Netflix makes clichés come true. This miracle of internet science and broadband technology offers something for everyone while being all things to all people. One part programmer and producer of original content like a TV network, and one part digital, easily navigable video store with instant watch capability, Netflix offers thousands of entertainment options of every genre of movie and TV, from original groundbreaking projects to films both obscure and extremely popular. In other words, it's an embarrassment of cinematic riches, and it's irresistible — Netflix is the world's most popular streaming service, still outdrawing its competitors in an industry it more or less invented before platforms like Hulu, Amazon Video, and Disney+ joined the fray.

The Netflix story is big and fascinating, full of heroes, dreams, influence, world-changing ideas, and fortunes gained and lost. It would all make for a great Netflix limited series. Until then, here are some little-known facts about what really goes on behind that familiar red logo.

The real reason Blockbuster didn't buy Netflix

It's on most every list of shortsighted, ill-conceived, or just plain bad business decisions: Blockbuster Video turned down the chance to buy Netflix. In 2000, the fledgling home video upstart offered itself up to then-industry leader Blockbuster for $50 million, and Blockbuster execs said "no thank you." The company instead went all-in on a broadband-based entertainment delivery service with Enron, subject of one of the most scandalous and disastrous corporate collapses in history barely more than a year later. Netflix, meanwhile, grew to generate billions and dominate on-demand home entertainment, while Blockbuster no longer exists.

But there's a lot more to the story. When Netflix put itself up for sale, it was hemorrhaging money and wasn't nearly worth its asking price. Nor did it want an outright Blockbuster takeover, suggesting instead that it run Blockbuster's online storefront. Basically, Netflix swaggered up to a massive company and asked for $50 million and exclusive use of its brand. It makes sense that Blockbuster executives rejected the idea.

The Netflix origin story is a myth

The inspiration for Netflix is a tale often told, and it's a very entertaining and relatable one, pointing out perfectly the flaws of the video industry which Netflix was able to avoid and thus wildly succeed. The story goes that Netflix co-founder Reed Hastings was inspired to start the business after returning a copy of Apollo 13 to a Blockbuster Video way past its due date and getting hit with $40 in late fees. Hastings so resented Blockbuster's audacity and greed that he vowed to find a way to get DVDs to customers without charging late fees. The Netflix model: Movie fans paid a monthly fee to have a certain number of DVDs at home, which they could keep for as long as they liked, or return them ASAP and get a new movie sent. As great as the story is at putting a neat little bow on the founding of the company, it's completely made up. Hastings basically invented it for interviews because the actual story of Netflix's creation is long, complicated, and full of dull business jargon.

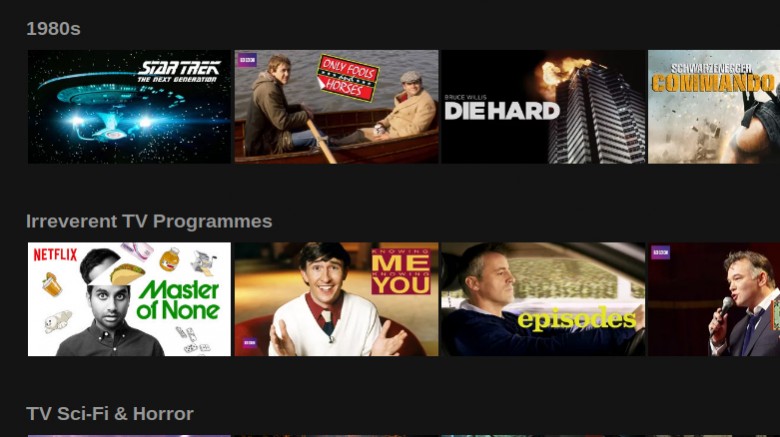

The site has quite a few "micro-genres"

As you'd expect for a company with thousands of films in its archives, Netflix meticulously catalogs every film in its library. Unlike us peons, though, who are happy enough dividing films by their genre or how much nudity they contain, Netflix takes everything into account when it adds a new film or TV show to its library.

Netflix's proprietary algorithm sorts films based on everything from historical settings to whether or not it contains vampires, allowing them to cater to almost ludicrously specific tastes. As an example of how laser-like the focus of Netflix's genre algorithm is, for an April Fool's joke they once suggested users check out "Movies Featuring an Epic Nic Cage Meltdown." Which may as well have just been a list of every Nic Cage film, but you get the idea.

In 2014, a curious statistician worked through the code of Netflix and found the site has over 75,000 different "micro-genres" that it uses to categorize movies and shows (76,897 to be more precise). For example, 4082 leads to "Action & Adventure based on a book from the 1960s" while 45028 means "Deep Sea Horror Movies." Netflix isn't forthright about the codes, but they're easily and directly accessible when using Netflix with a web browser. Type in "www.netflix.com/browse/genre/" into the navigation bar, and then type in a random three-, four- or five-digit number and just see what happens.

Netflix tracks everything its customers do

What's the most important thing Netflix owns? Exclusive rights to stream numerous blockbuster movies? A cut of the merchandising for Stranger Things? Nope — it's the data of its massive subscriber base, which those same viewers generate every time they watch something on Netflix.

Along with collecting basic data from subscribers (e.g., the shows they watch, at what time, and for how long), Netflix pinpoints when you pause, rewind, or stop watching something in an attempt to figure out why. This data on its own isn't all that useful, but when cross-referenced with basic geographical information and the same data produced by the other 70 million odd Netflix subscribers, it can be used to produce comprehensive charts detailing exactly what people watch. Netflix sadly keeps this data to itself so we'll never know just how many people stop watching Adam Sandler movies the second Kevin James turns up.

Along with helping Netflix decide what to purge from its library, the data is an invaluable tool for Netflix when it produces original content, allowing the service to confidently predict exactly how many people will watch a particular original program and set an appropriate budget. So remember, the next time you press pause, you're holding the fate of your favorite streaming stars in your hands.

Netflix doesn't make shows like other companies make shows

Because Netflix isn't beholden to advertisers and has a largely guaranteed revenue stream from subscribers, the company will often order two seasons of any show it produces rather than a pilot. Actors and writers have credited this with giving them a greater degree of flexibility when creating shows as they don't have to rely on gimmicks like cliffhangers to retain viewers. Instead, they can focus on simply creating good content. This is one of the reasons some episodes of original Netflix shows are different lengths. The writers aren't restricted to the usual time constraints of regular TV so they can make an episode as long or short as it needs to be.

Also, because of the vast wealth of statistics about viewing habits Netflix has at its fingertips, the company abstains from micromanaging shows because it knows they will succeed. The best example of this is probably House of Cards. Netflix had no qualms about giving director David Fincher approximately $4 million per episode because they had data showing that users loved the original British series. On top of that, the stats showed audiences were big fans of Fincher and Kevin Spacey and rated their respective films highly. As a result, Netflix pretty much knew the show would be a hit before it even aired, because the match indicated that it would.

They're pretty cool about overtime and expenses

Netflix is surprisingly hands-off when it comes to the management of its employees, which is pretty unusual for an omnipresent, monolithic media company worth billions of dollars. In fact, full-time workers in Netflix's main office are basically allowed to set their own hours, with company policy stating that an individual employee can take off as many days as they feel they need. The policy is so lax that if you want to take off more than 30 days in a row, all you need is the okay from a manager.

The reasoning behind this, from Netflix's point of view anyway, is that if you hire good employees and treat them like adults, they can be trusted to make good decisions. This ethos is best summed up by Netflix's official expense policy which goes, "Act in Netflix's best interests."

Employees can pretty much request expenses for anything they like, but they're asked to spend the money like it's their own. Despite seeming like such a system would be massively open to abuse ("Hello, 30 new laptops") it works and functions with little actual oversight, with executives noting that the only real people they have to keep an eye on are the IT guys because they always request fancy gadgets and toys for their office.

Netflix doesn't care about account sharing

According to a study by Global Web Index, Netflix may lose as much as half a billion dollars a year as a result of customers sharing their accounts with friends and family members. Such a revelation would reasonably make the executives of most companies fly into fits of panic and fury, but not Netflix. The service's top-ranking employees are well aware that a large percentage of their users aren't technically paid subscribers, and they don't really seem to care, either. "We love people sharing Netflix," CEO Reed Hastings said at the 2016 Consumer Electronics Show (via CNet). "That's a positive thing, not a negative thing." In an interview with Barron's, Hastings acknowledged that password sharing was "something you have to get used to. Because there's so much legitimate password sharing." The company even actively encouraged users to share the same account by offering subscription packages that let multiple users watch at once on multiple devices.

Netflix might be heading for stricter enforcement policies. In 2019, with Netflix as a charter member, the Alliance for Creativity and Entertainment formed, acting as an entertainment industry trade group dedicated to fighting streaming privacy, including unacceptable password sharing.

The Netflix library is influenced by pirates

In addition to tracking what shows its customers watch and how often they pause them, Netflix also employs analysts who track exactly what the world's most stingy entertainment enthusiasts are torrenting online.

Like the data it collects from subscribers, piracy figures represent an invaluable insight into viewing habits that Netflix uses to adjust its own programming. After all, if people are willing to give their computer an STD to watch Game of Thrones or Arrow, it probably means someone is willing to pay a few dollars to watch a similar show from the comfort of their toilet.

Netflix has even been reported to use the geographical data of pirates to adjust its pricing, lowering the cost of their service in areas with high rates of piracy in an attempt to lure pirates over to the SS Netflix and Chill. It's a sentiment that kind of reminds of us this famous quote by Gabe Newell: "The best way to combat piracy is by offering consumers better service than they might get from the pirates."

Indeed, Gabe. Indeed.

How Netflix became Netflix

Plenty of big online companies found success in spite of a name that's made up, nonsensical, or derived from an obscure word in a language other than English. ("Etsy" and "Hulu" weren't exactly familiar words 15 years ago.) But Netflix? That just makes sense — it employs the power of the internet (net) to watch flicks (flix). It took company founders a while to put that portmanteau together. Before deciding on Netflix, names like Replay, Directpix, CinemaCenter, NowShowing, eFlix, and Kibble were all under various levels of consideration.

A company's perception is more than just its name, however. Plenty of businesses make an impression with an advertising jingle, and Netflix kind of has one of those. When users start up a Netflix original production, they're greeted with a deep, well-rounded "dum-dum," the most famous two-note sequence since the Law & Order scene change sound. It's widely assumed to be derived from a noise heard in the very last scene of the last episode of the second season of House of Cards, one of the very first Netflix original shows. The conniving Frank Underwood (Kevin Spacey) triumphantly slams his first down on his desk, twice, in rapid succession.

With Friends like that, who needs Friends?

Despite numerous original series and an array of movies, the thing Netflix viewers want most are old, comforting sitcoms. In 2019, media strategist Scott Lazerson revealed (via People) that the network's two most popular overall shows were the American version of The Office and Friends. Friends hit Netflix in 2015 at a cost of $30 million per year, a contract the service renewed in 2018, forking over a whopping $100 million to keep the digital streaming rights to the adventures of Monica, Chandler, Joey, and such for just one more year. In 2020, Friends moved to HBO Max (a new streaming player in a market essentially created by Netflix), which paid a stunning $425 million. The Office, a Netflix standard offering for years, won't stick around either, jumping to NBC's Peacock digital streaming outlet in 2021 at a cost of $500 million. That leaves Netflix without its two most attractive properties, but it also freed up hundreds of millions of dollars, which it could use to buy up more reruns of extremely popular dead sitcoms. In 2021, Seinfeld leaves Hulu for Netflix, a privilege which cost the service, according to the Los Angeles Times, "far more" than what Peacock paid for The Office.

Netflix's investment costs are ultimately absorbed by the customer. Its subscription fees have climbed over the years, with the standard package getting a $2 increase right after the $100 million Friends deal.

What's a "Qwikster" anyway?

By late 2011, Netflix's entry into streaming was so successful that it looked to permanently overshadow what had previously been the company's core business: DVD rentals by mail. So, in a blog post (via HuffPost) in September 2011, CEO Reed Hastings revealed that Netflix would split apart. "Netflix" would be the home for online streaming, while the DVD-by-post service would be spun off into a new and completely separate service called Qwikster. "We realized that streaming and DVD by mail are becoming two quite different businesses, with very different cost structures, different benefits that need to be marketed differently, and we need to let each grow and operate independently," Hastings wrote.

A solution to a problem that most people didn't know existed? Not really. Launching Qwikster was a big corporate move made to stanch some financial bleeding. Netflix instituted a price hike in July 2011, which cost the service so many customers that it messed up its growth projections and caused the Netflix stock to nosedive. Some financial analysts speculated that making the DVD business a separate entity was Netflix's attempt to sell off that division, allowing it to focus its efforts and resources on the growth industry of streaming. But nobody stepped in to buy Qwikster, and after three days of nasty public backlash, the company reversed course and kept its DVD business under the Netflix umbrella.

Not playing on Netflix, not now or ever

Netflix customers can stream a little or a lot of everything, and since not every movie and TV show is excellent, the service certainly has its share of stinkers. It also produces more original content than any person with a life could keep up with. In other words, it doesn't seem like Netflix ever rejects any content offered up by producers or distributors, but even the world's largest virtual video store says no sometimes. According to a tweet by film industry writer Alonso Duralde, Sony was so dismayed by low audience test scores for the 2018 Will Ferrell comedy Holmes and Watson (which went on to win the Razzie Award for Worst Picture of the year) that it offered it to Netflix as a straight-to-digital release, and Netflix turned it down.

Netflix also passed on three of the most acclaimed and original TV series of the 2010s, all of which went on to win awards for other carriers. According to Netflix chief content officer Ted Sarandos, his company let Amazon Video have Transparent, Hulu have The Handmaid's Tale, and USA land Mr. Robot. "A lot of times, it's not the reflection of the show," Sarandos told Variety. "It's just timing."

The origin of "Netflix and chill"

Netflix is undeniably part of the fabric of American life — and life in dozens of other countries, too. The streamer's original shows (like Stranger Things and Making a Murderer) routinely become cultural phenomenons and national obsessions. It even influences modern English, giving us colloquialisms like "binge-watching" and euphemisms like "Netflix and chill." (For those out of the loop, that's a phrase that when texted or spoken, it's an invitation to one's bedroom or living room under the pretense of watching a movie on Netflix, with both people understanding that what they're really there to do is engage in an act of unclothed physical pleasure.)

"Netflix and chill" is part of the vernacular now, popularized in the mid-2010s through various forms of social media. Reporter Kevin Roose tracked down the first utterance of the phrase to 2009, when Twitter user "@nofacenina" wrote, "I'm about to log onto Netflix and chill for the rest of the night." That person is describing a solo activity — literally watching Netflix and doing literally nothing else. It wasn't until summer 2014, after a vast many other Twitter users wrote out the phrase, that it reached its final state as a randy come-on.