The Untold Truth Of 2010: The Year We Make Contact

In its day, 2010: The Year We Make Contact was a confusing proposition. It arrived decades after the original 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film that achieved a level of cinephile devotion almost too impossible a benchmark to rise to. It had a clear narrative which was not beholden to Stanley Kubrick's cold narrative and psychedelic surrealism, instead injecting political intrigue. It was met with faint praise in its time, likely in deference to its legendary forebear.

Nearly 37 years later, a reappraisal is long overdue. 2010 was more faithful to sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke's source material, the novel 2010: Odyssey Two, than 2001 was, as the latter was famously cobbled together from bits and pieces of Clarke's short stories (primarily "The Sentinel"), leaving the novelist the strange task of writing an adaptation of someone else's adaptation of his own work.

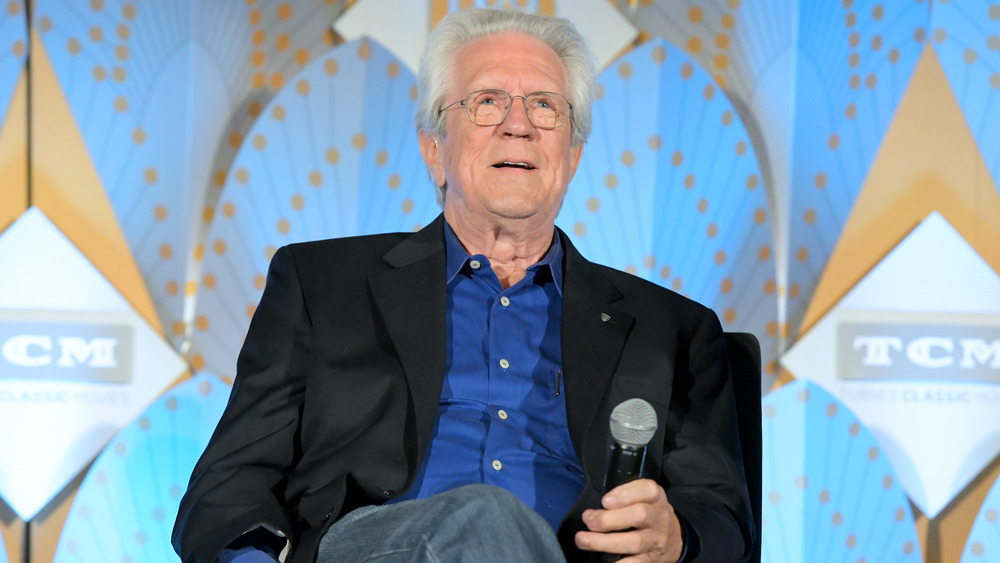

Thanks in part to screenwriter, producer, director of photography, and director Peter Hyams, 2010 has aged very well, presenting a compelling story with some of the best visual effects of its era.

A forced blank slate

After the production of 2001 A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick had all the materials destroyed, making a 100% accurate sequel almost impossible. The long-held opinion of why suggests you blame it on Shakespeare.

Rather, blame it on Forbidden Planet, the famous MGM sci-fi classic based on Shakespeare's The Tempest. In the film, a hulking robot steals scenes from the star Leslie Nielsen. Years later, that same robot, named "Robby," was seen in numerous films and TV shows, including The Invisible Boy, The Twilight Zone, The Addams Family, Lost In Space, Mork and Mindy, Gremlins and others. It was a fairly common practice for the movie and television industry to recycle props, costumes, and even scenery from other productions.

The book The Complete Kubrick paints the picture of the director not having any desire to revisit the story of 2001. Destroying the materials from the film was purportedly to keep them out of the endless recycling churn. It did not make the task easy for the people who would have to come after Kubrick to recreate that world, but not everyone was apparently as committed as Peter Hyams and his team.

Having made a splash with the lunar landing conspiracy film Capricorn One (a movie that helped spark the "Kubrick faked the moon landing" meme), Hyams reluctantly jumped into his role.

2010, a more faithful representation

As Arthur C. Clarke stated in the documentary for 2001: A Space Odyssey's DVD, Kubrick notoriously hated science fiction, feeling it was mostly space operas and westerns in the cosmos. He purchased the rights to several of Clarke's short stories, seeking source material to work with. Ultimately, he chose "Encounter in the Dawn" and "The Sentinel" as the primary stories to draw upon, the latter being the dominant narrative. Kubrick and Clarke then reshaped these into the story we know today, with Clarke writing a novelization based on their final work. As for those other rejected stories? Clarke laughed, "I bought them back!"

This brings us to 2010: Odyssey Two, Clarke's sequel novel that was published in 1982. While 2010 writer-director Peter Hyams made a few significant changes to the adaptation, it is largely faithful to many elements of the book.

Given the specificity of the source material this time around, the movie was bound to be more structured, less conceptual. And in fact, the story is a meditation on regret: both with Dr. Heywood Floyd's guilt for the apparent deaths of astronauts Frank Poole and David Bowman, and with Dr. Chandra's unanswered questions about why his creation, the HAL 9000 computer, became murderous.

Getting the blessing, but not much else

Peter Hyams needed to prove to both Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick that he wasn't going to do retroactive damage to what the two created with 2001.

First, he had to get Clarke on board with a major change from 2010: Odyssey Two, wherein the American and Russians are allies in solving the mystery of the deaths on the Discovery spaceship. Science fiction often comments on the present, even if it's set in the future. 2010 was released in 1984, a year where tensions between the two superpowers were coming to a head. There was doubt that audiences during the Reagan administration could take that leap. Hyams convinced Clarke that the USA and USSR had to collaborate.

Now Hyams needed Kubrick's nod. As he stated in an interview with the website Film Talk, "I remember our first phone call...He kept on asking me a lot of technical questions, how I did this or that shot. At the end of this three hour phone talk, I asked him, 'Mr. Kubrick, I would like to know if you approve me doing 2010.' He said, 'Sure, of course.'"

Peter Hyams, also an auteur

Stanley Kubrick is famed as a director who was intimately involved with every aspect of his filmmaking. He was known for uprooting talent and moving them to England not for weeks or months, but for several years.

Peter Hyams seldom gets similar accolades. 2010 was not as groundbreaking as 2001, and it falls in the traditional category of science fiction films. In multiple interviews, Hyams expressed the reluctance he felt in jumping into the project. "I kept saying no (to MGM)," Hyams said in an interview with Empire Online. "The idea of being compared to Stanley Kubrick is laughable. You can't compare me to him without it being very unfavorable."

Hyams persevered with a personal mission to not carbon copy the original. "It was daunting and frightening," he told Den Of Geek. "I figured that when I made 2010, the only thing I could do was make a film that was so different in approach and style, that it simply could not be compared. And I don't think you can compare. It's just so different."

2001's complicated carryover characters

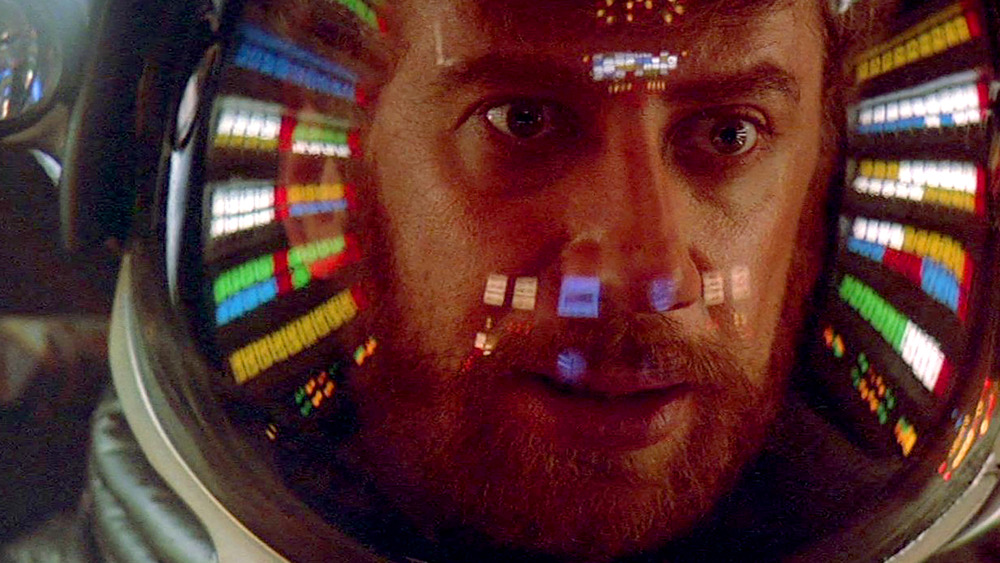

There were three characters left alive at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, depending on your definition of "alive." HAL 9000, voiced by actor Douglas Rain; David Bowman (Keir Dullea), and Dr. Heywood Floyd. Originally portrayed by William Sylvester, Floyd could easily be described as a "suit," an employee for the National Council of Astronautics (NCA) who barely retains curiosity for what lies beyond. It's just his job.

2010 was going to focus squarely on Floyd, and required an actor with a recognizable face and name who could carry the film. The affable Roy Scheider took on a role that was oddly similar to his famous turn as Chief Brody in Jaws – that of a man seeking answers on the verge of the unknown.

Keir Dullea and Douglas Rain, however, were essential. An argument could be made that Dullea's performance in 2010 is even more iconic — albeit briefer in total — than in 2001. The film opens with a recap of the events of the Discovery section of 2001, prefaced by Dullea's disembodied voice exclaiming, "My God, it's full of stars!"

Later in the film, Floyd is in the process of restarting the abandoned Discovery spaceship and is stunned by a message coming through the onboard computer: "Look behind you." It is Bowman...sort of. Is he a ghost or a new being altogether? He cycles through the stages of life again and assures Floyd that something is about to happen, "Something wonderful."

A strong supporting cast

The transformed essence of David Bowman (Keir Dullea) informs Dr. Heywood Floyd (Roy Scheider) that it will not be safe for the combined crew of Americans and Russians to remain in Jupiter's vicinity. Worse, tensions back on Earth have forced the same Americans and Russians to separate. To survive an event that is going to happen regardless of political conflict, the space travelers will have to defy their governments and work together.

In addition to the primary actors, 2010 features John Lithgow, Bob Balaban, and Helen Mirren in memorable performances. Balaban played Dr. Chandra, the computer scientist who created HAL 9000 and has been haunted by its murderous, catastrophic failure. The film's tension relies on whether or not he can be trusted. Given he is the only person capable of restarting HAL on the abandoned Discovery, Floyd is forced to accept Chandra's word that his intentions are good.

John Lithgow injects humor into the story as Dr. Walter Curnow, a reluctant space traveler. In a memorably tense scene, Curnow suffers a panic attack while attempting a space walk.

Helen Mirren had the most difficult role in 2010, given the Cold War tensions of its audience in 1984. As Captain Tanya Kirbuk, the commander of the Alexei Leonov upon which the Americans "hitchhike" to Jupiter, she has to be tough and not necessarily someone we trust, but someone audiences still empathize with.

Attempting visual effects veracity

Hyams and company sought to be as faithful to the imagery of the original film as possible, but it would not be easy. As per Stanley Kubrick's direction, there was no production collateral left to study.

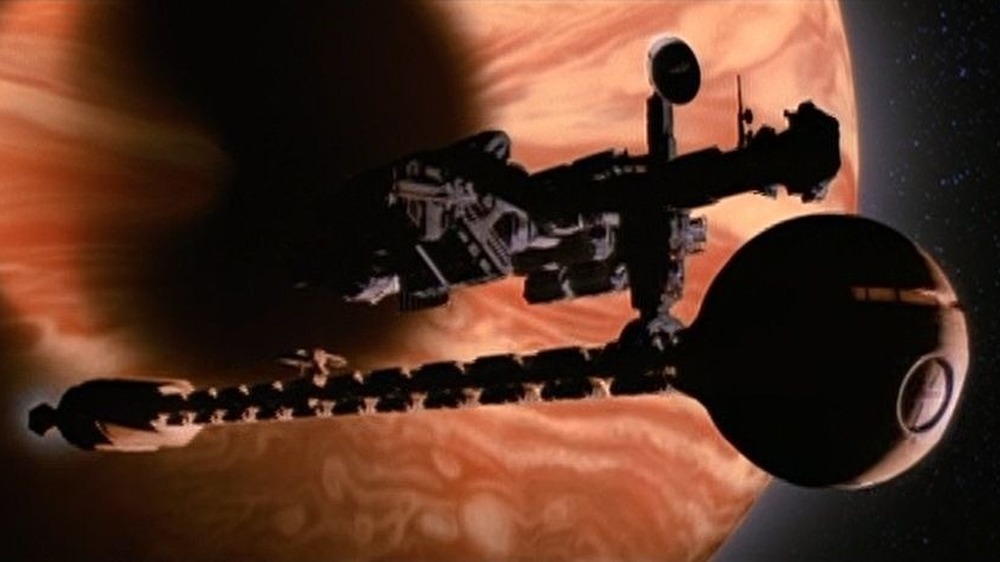

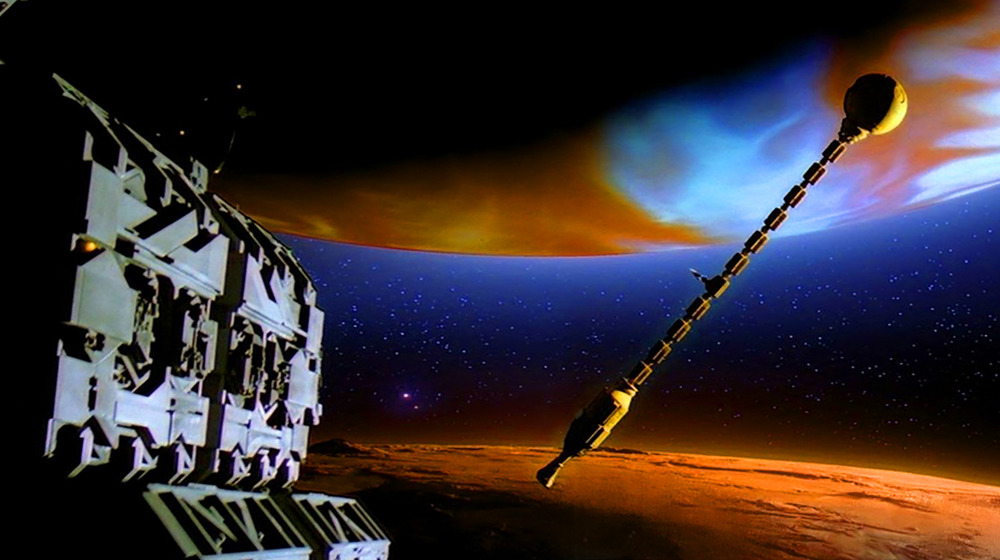

The Russian ship, the Leonov, was designed by famed futurist Syd Mead (Blade Runner) who said its aesthetic was, "Minimal cost for the maximum utilitarian value. If I had to describe in one word. the look of the hardware I designed for 2010, it would be 'functional.'"

Production designer Albert Brenner had to rebuild the interiors of the Discovery for the film based on images from the original. There are significant differences, specifically in scale. Kubrick's Discovery interiors are all claustrophobic corridors and cold, antiseptic lighting. 2010's Discovery spaces are a bit wider, with the lighting leaning toward a naturalistic blue-white tone.

2010's effects were done by Boss Film Studios under famed effects supervisor Richard Edlund (Star Wars, Ghostbusters). "Mark Stetson and Les Eckert, the guys who were running the model shop at the time, had to photo-interpret frames from 2001 to recreate plans for the Discovery model," Edlund told Looper.com. This meant blowing up frames from 2001 to extremes and painstakingly recreating plans by sight.

Richard Edlund, in his own words

Yes, Kubrick told Peter Hyams he could make the movie, but he was not enthusiastic about it. This left Richard Edlund with the unenviable task of recreating accurate visuals with no help from Kubrick's camp whatsoever.

Looper.com asked Edlund, the effects supervisor for 2010, Ghostbusters, Big Trouble in Little China, and the majority of your childhood, about some of the difficulties in making the movie's breathtaking visuals.

"We shot the (Discovery) models before blue screen in the front-light-back-light method, on Kodak Eastman's 5247 film stock because of the quality, not with the higher speed films that were available at the time." Edlund said.

"This brought some challenges," he continued. "You shoot the 'beauty pass' (the primary image of the model) against black. The model is shot with a 10k light — a pretty bright light — and you're shooting one frame per second or even less, going nearly an hour or so. Then you reshoot with a white screen lit behind the model, and that darkened area where the model is photographs as clear. You can make mattes from that." The issue, however, is that because of the hot lights on the model, the Discovery bowed slightly and didn't fit the matte: "A lot of rotoscope animation had to be done to fix those."

Lithgow on wires

"One of the interesting problems we had was shooting the space walk with Curnow (John Lithgow) and Brajlovsky (Elya Baskin)," Richard Edlund told Looper.

2001: A Space Odyssey debuted in 1968, one year before Americans landed on the moon. Finally, people knew how black space really was and how little fill-light was out there to illuminate objects. The problem with effects in the 1980s was the need for blue screens, which would bounce a bluish kick on your subjects if you don't overlight them to flood it out. Underlight them and you would get a blue fringe around actors or models. Overlight them and it no longer looks like objects in space.

"We created a blue front-projection system with a 25 x 60 foot screen we had to make," Edlund explained. "We hung that on the stage and then shot the actors with the front-projection system so we could light them with one light without the fill. We could get the shadows on them as black as space."

It worked. The scene of Curnow having a panic attack during the space walk is one of the most suspenseful in the film. "It was kind of a nightmarish thing having the actors hanging there on wires, but it turned out really well," Edlund said.

A straightforward narrative

The storytelling in 2010 was bound to be very different from its predecessor. Stanley Kubrick constructed 2001 from several short stories he optioned from Clarke, with the dominant story being "The Sentinel." In it, an object is uncovered on the moon, and upon its discovery, it sends a signal throughout the universe warning that humans have escaped the confines of planet Earth.

Although Peter Hyams needed to make big changes to Arthur C. Clarke's sequel novel, 2010: Odyssey Two, these were made with Clarke's oversight and approval. This was achieved by setting up a sophisticated (for its day) Internet connection between Hyams in the U.S. and Clarke at his home in Sri Lanka.

Hyams and Clarke intended to make Heywood Floyd a central character, not part of a transitory vignette as in 2001. He was there to find out why HAL 9000 murdered Discovery pilots Frank Poole and David Bowman. As such, 2001's mind-bending flight through human history, ending with the next step in the species' evolution, was too abstract for what the two creators hoped to achieve with its successor.

In retrospect, it is that straightforward approach that makes 2010 so intriguing. It offers some answers to the questions the previous film posed, but doesn't give up all of its secrets.

A more humane tale

2010: The Year We Make Contact walks back a central premise of 2001: A Space Odyssey: that the universe is neither good nor bad, but is indifferent to the wants of its inhabitants — in the big picture, small stuff like people flying around attempting to figure it out is just an eyeblink in the expanse of time. It's why the characters in 2001 seem so cold and officious, viewed with universal objectivity.

On the other hand, 2010: The Year We Make Contact is a highly subjective, and decidedly human story centering on regret and guilt. Dr. Heywood Floyd (Roy Scheider) is a man caught up in a failure with his name attached to it but no clear answers why it happened. He'll leave his family behind to solve the mystery and there is a grave possibility it is a one-way trip.

Dr. Chandra (Bob Balaban) created the operating system of the Discovery, which inexplicably decided to kill the crew. He has borne the brunt of responsibility while, at the same time, knowing the harm HAL 9000 inflicted was never a part of its programming.

While the universe remains indifferent to us, 2010 suggests we have a responsibility to not be indifferent to each other, and when the times call for humans to work together, we'll need to step up to that challenge.

Time has been good to 2010

37 years after its release, a reappraisal of 2010 is overdue. The film didn't reshape cinema like its predecessor, but there's still something potent and chilling about the disembodied voice of David Bowman (Keir Dullea) uttering in amazement, "My God, it's full of stars!"

Modern viewers come away with an appreciation of a well-told story that honors the original movie while being its own creation. Some mysteries are revealed while others remain. Who is David Bowman now? A ghost, an ambassador for the higher intelligence within the monoliths, or both? And what happened to Io, the moon of Jupiter now under the dominion of this universal power?

When the viewer is allowed to drop the baggage of its famous forefather, 2010: The Year We Make Contact not only does a lot of justice to the story Arthur C. Clarke developed, but stands as a solid, thought-provoking entertainment in its own right.

It also stands as a testament to the craft of visual effects. Both 2010 and Ghostbusters, the two films that helped launch Richard Edlund's Boss Film Studios, were nominated for visual effects Oscars. "The two canceled each other out and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom ended up winning," Edlund said.

The golden age of visual effects

One could say that a golden era of visual effects ended in the early 1990s when Richard Edlund's colleague, animator Phil Tippett, saw CGI effects proposed for Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park. His remark, "I think I'm extinct," was jokingly added into the script of that movie.

Edlund speaks wistfully of the magic of visual effects and their apparent passing: "CG has become somewhat a rocket science and effects are a commodity." Indeed, there is no mystery when something fantastical appears on the movie or TV screen — they came from a computer.

Fortunately, films like 2010: The Year We Make Contact remain, filled with imagery that, aside from the romance of their handmade nature, still provoke awe for audiences. Remembering the Alexei Leonov's attempt at escape velocity while monoliths engulf Jupiter, turning it into a star, combined with a story that centers on that human heart beating underneath, very little can compare.