Why Blade Runner Is The Best Sci-Fi Movie Of All Time

We've been collectively brainwashed into thinking of box office draw as a definitive metric, and that's a little tragic. Obviously, a movie that makes a billion dollars has more short-term cultural impact than one that doesn't do as well. But a film's immediate financial pull is not the be-all, end-all. For proof, look no further than Blade Runner.

During the summer of '82, Blade Runner (based on Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) only racked up about $26 million off a $30 million budget, according to Variety. But while it was initially considered a severe disappointment, not quite 40 years later, calling Blade Runner the greatest sci-fi movie of all time isn't even much of a hot take. In fact, it's a pretty common opinion.

Some credit for that belongs to the proliferation of home video throughout the '80s and '90s, as well as director Ridley Scott taking the opportunity to release multiple re-edits over the years. (This might be a good opportunity to establish we're talking about and spoiling The Final Cut – not necessarily any of the other versions — in this article.) But the most credit of all belongs to Blade Runner itself for being so great.

Blade Runner is better than 2001: A Space Odyssey. Blade Runner is better than Back to the Future. If Star Wars counted as sci-fi (which it doesn't because it's fantasy set in space, and that isn't the same thing), none of the Star Wars movies could compete with this classic. Why do we feel this way? Feast thine eyes upon the reasons.

Blade Runner has a massive scope of influence

To be clear, anxiety surrounding the prospect of sentient technology provided a basis for sci-fi and horror stories way before Philip K. Dick came up with Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? in 1968. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein predates Dick's era by more than a century, and it expresses similar concerns about the hypothetical treatment of an artificial humankind that the OG humankind might create someday.

But when we take a story about self-aware tech, set it in a densely packed city during a post-global catastrophe future, add in loads of kinetic action sequences, pack it with philosophical angst, and make sure it's raining constantly, well, that sounds like a familiar recipe, doesn't it? Reminds you a little bit of Akira, Ghost in the Shell, and The Matrix, yeah? That's because Blade Runner set the template for those and other stories in the cyberpunk sub-genre, which has since become influential across virtually all media. For a prominent recent instance, consider HBO's Westworld. Although based on a 1973 TV movie that more-or-less predates the sub-genre, the modern version fully embraces cyberpunk tropes like quasi-omnipotent corporations, a future dystopia, and melodramatic robots.

Setting cyberpunk aside, we could even reach a little further and suggest the synthetic characters in Terminator 2, Her, and Ex Machina all develop their more human qualities in a manner reminiscent of Blade Runner's replicants.

Blade Runner's soundtrack perfectly complements the film

We don't have enough space to really do justice to Blade Runner's original soundtrack and its broader implications for the entire landscape of electronic music. So let's just focus on what it accomplishes during two key points — the opening and closing credits.

Right at the launch, before a single visual component enters the picture, the music tells the audience that the world of this movie is very pretty and falling apart. We hear a distant, deep thwack. Then another. A sweet, doomed melody continues for a moment before collapsing. Then, another thud echoes in space. The tension between the minimalist percussion and the high notes coasts into an exposition scrawl that reveals, "Early in the 21st Century, the Tyrell Corporation advanced robot evolution into the Nexus phase — a being virtually identical to a human — known as a replicant." And with that, we're off to the Los Angeles skyline, which is beautiful and, disturbingly, on fire.

About two hours later, an elevator door slams shut, and the adventures of Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) come to a temporary close. The propulsive, buzzing end titles theme lends an unusual degree of oomph to the closing credits, which typically serve to wind down, rather than wind up, an audience. But the sonic elevation suits the outro for Blade Runner. The story lacks an explosive ending, but it nevertheless warrants the exclamation point that composer Vangelis elegantly tags on.

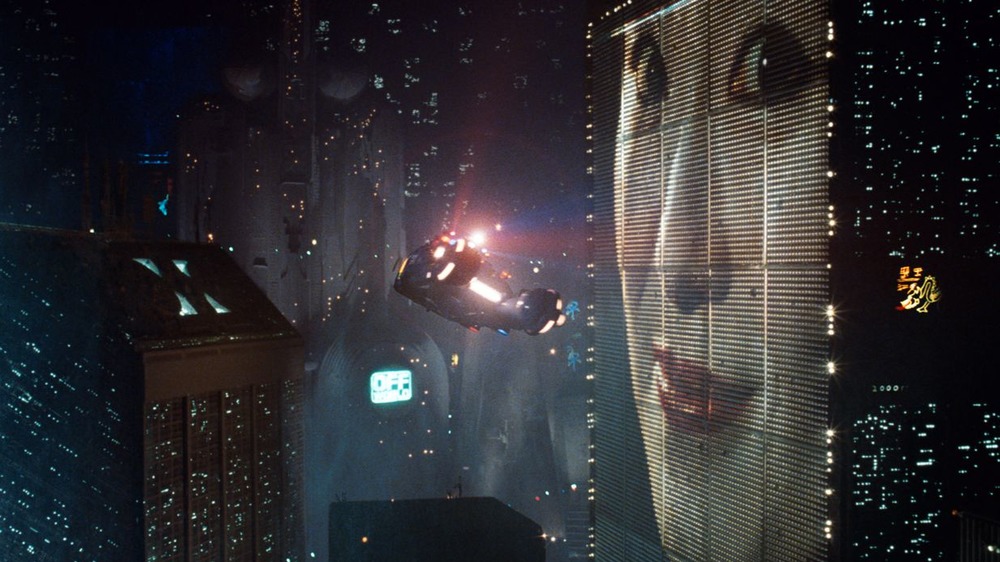

The aesthetic is absolutely amazing

The Los Angeles of Blade Runner's 2019 looks gorgeous, as long as you don't think about it too hard. It even has its share of advantages over what Los Angeles was like during the actual, real-life version of 2019. "There's no housing shortage around here," J.F. Sebastian (William Sanderson) casually muses during his first encounter with Pris (Daryl Hannah). "Plenty of room for everybody."

A major American city with cheap and plentiful apartments for rent sure doesn't sound too dystopian. However, the municipal planners apparently only created such favorable conditions by making sure every building literally scrapes the clouds. From a distance — like in the several birds-eye-view pans across town — window light and neon corporate advertisements sparkle through hulking, awe-inspiring obsidian structures. Close up, the same architecture appears shambolic, corroded, and uneven — reality's equivalent to being slapped together with Duct tape.

It's a great place to live as long as we, under no circumstances, ask why we never see any sign of plant life. Or, for that matter, why is it always so dark? When does the nighttime stop? What happened to the sun? Trust us, you don't want to know, but if you don't think about all the dark implications, you can truly marvel at Blade Runner's beauty.

The film features Harrison Ford at his most interesting

A generalization about Harrison Ford's range as an actor would be unfair and misguided, so we're not making one of those. But Han Solo and Indiana Jones are the same guy. They're quipping, cynical, slightly anti-heroic swashbucklers, and that's the archetype we expect Ford to embody when he shows up in a movie. But Rick Deckard in Blade Runner is not the same guy.

Like Solo and Jones, Deckard is an individualistic man of action. Also like Solo and Jones, he doesn't take no for an answer, and by that, we mean he has very serious issues with consent. But for Solo and Jones, life is dangerous but also fun and exciting. They're joined by sidekicks and friends who soften their gruffer tendencies. And they inhabit worlds where the difference between good guys and bad guys never gets questioned.

Meanwhile, Deckard never tells jokes while he's shooting at people. He doesn't go on adventures. He does a brutal, upsetting job that drives him to possible alcoholism. He's emotionally and psychologically damaged by the total mystery of his past. His world is absolutely loaded with moral ambiguity. Deckard's not the opposite of Han Solo or Indiana Jones — he's a remix of Ford's signature archetype. Some of the knobs on the metaphorical soundboard are turned down, others are cranked way up.

Wait ... Deckard's the bad guy!

A casual viewer can soak in Blade Runner, more or less accept it as a visually breathtaking sci-fi action tale, and walk away satisfied. Deckard is the protagonist, played by an actor we recognize from previous heroic roles. He kills the criminals he's told to kill at the beginning of the story, and then he gets the girl. From that perspective, Blade Runner follows a familiar, comforting formula.

But wait. Deckard is ordered to execute Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) and all of his friends on sight without any due process, for the sole crime of existing on a planet they're not supposed to be on. That doesn't quite seem fair, does it?

Why can't Roy sue the Tyrell Corporation for a life extension? Why can't he hire an attorney to help him make a case before a jury of his peers? Well, he can't because replicants don't have rights. Under the law, they're not considered people. But who gets to decide who counts as a person?

In this case, humans function as a metaphorical majority that, by the mere unchallenged virtue of being the majority, dictates the norm. This social paradigm leaves those who fall outside the norm — replicants, in this case — open to exploitation and abuse. It's almost as if Deckard, by working to uphold unjust laws, is a trooper in some sort of empire, and Roy is rebelling against that empire. In fact, Roy is part of a whole entire alliance of rebels. Hmmmm.

What if we're all replicants?

Ever wonder if you're really you? A lot of the characters in Blade Runner sure do.

Early in the film, Rachael (Sean Young) learns that everything she thinks happened in her life before working at the Tyrell Corporation isn't real. She didn't exist until she was bio-engineered by Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel), who stuffed her brain full of memories that he somehow lifted from his niece. Her identity is based on lies. Deckard doesn't mention much about what his life was like before he started blade running, either. This opens up the possibility that Deckard is one of the things he's paid to hunt, in which case, his identity would also be based on lies.

If our idea of who we are is formed by past experiences, and memories can be altered, then how can we hold onto any fundamental assumptions about our realities? How can anyone in the world of Blade Runner know they're not a replicant?

While Deckard and Rachael's struggles with existential confusion don't provide much in the way of plot points, the theme of mutable identities gets fleshed out significantly in the sequel, Blade Runner 2049. But even if that concept isn't fully explored in the original, it's still there, lurking in the shadows. There are countless sci-fi stories about robots in the future, but Blade Runner is one of the very few that confronts the nature of consciousness without getting way self-indulgent and into itself about it.

Blade Runner's opening scene is way underrated

Rick Deckard isn't the first character we encounter in Blade Runner. He's not even the first blade runner. That designation belongs to the unfortunate Dave Holden (Morgan Paull). Charged with sniffing out possible replicants among the new recruits at Tyrell headquarters, Holden meets his end upon administering a Voight-Kampff test to Leon Kowalski (Brion James). After bungling a chance to help an imaginary turtle during this incredibly odd quiz, Leon recognizes he's been made and uses some bullets to turn Holden into Swiss cheese.

In theory, the events depicted in the first few minutes could've been covered by exposition dialogue later on. But even though it's inessential to the plot and introduces no main characters, the opening scene does a ton of heavy lifting with regard to establishing theme, tone, and even iconography. We learn that failure to register appropriate emotional responses to a Voight-Kampff test leads to dire consequences. The film presents us with a baseline of a law enforcement officer condescending to a bottom-tier corporate employee who's pretending not to panic and failing spectacularly.

What's truly fascinating is that Brion James delivers Leon's lines with deliberate awkwardness. Keep in mind, Leon's only a few years old. He's hasn't had much practice with basic small talk or hypothetical questions. He certainly hasn't had time to become a good liar. Ironically, the scene falls flat unless we can relate to Leon's fear. We empathize with Leon, so when we're later told his emotions aren't real, we aren't convinced.

Pris vs. Deckard is pretty intense

Blade Runner has taken its share of flak over the years for how it treats its female characters. A lot of those criticisms are ... ah, actually pretty spot on.

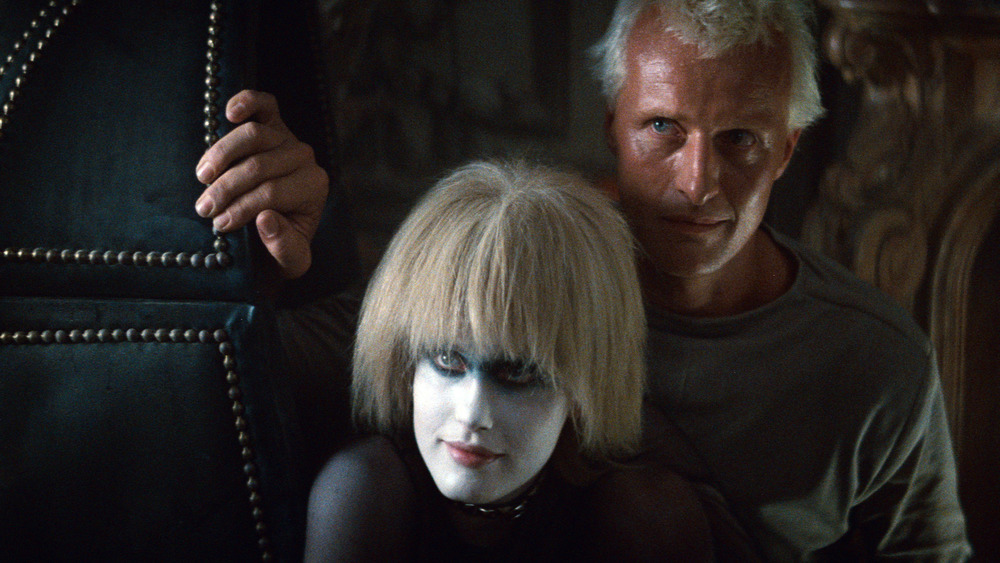

Essentially, there are three women in this movie. There's Rachael, who's Deckard's damsel in distress. There's Zhora (Joanna Cassidy), who shows her boobs and is then shot to death. And then there's Pris, who uses her lady charms to trick a nerdy virgin into doing something against his own best interests, which ultimately gets him killed. After that, Pris is also shot to death. Not a good look, Blade Runner!

Lousy with sexist tropes though she may be, Pris gets one of the most memorable action sequences and the one of the coolest death scenes in the film. Deckard catches a hunch that Pris and Roy might be keeping a low profile at the dwelling of genetic designer J.F. Sebastian. After a tension-building trip up the stairs of Sebastian's apartment complex, Deckard enters a room filled with bio-engineered toys. Pris sits motionless and hidden in plain sight among the nightmare vision of a child's playroom until she decides it's time to twist Deckard's head loose from the rest of his body. The ensuing confrontation is brief, loud, and thoroughly unsettling. It's the kind of grisly action scene that will stick in your mind long afterward.

Blade Runner gets you to sympathize with the 'villains'

Audiences aren't always biased in favor of prefabricated "good guys." Sometimes, they'll listen to a film's villain and wind up on the opposite side of the story's idea of conventional morality. For example, Eric Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan) sparked plenty of debate among Black Panther viewers in 2018. And in 2019, director Todd Phillips and Joaquin Phoenix re-imagined the Joker as a working-class hero — an awful working-class hero but a working-class hero nonetheless.

Similarly, it's easy to sympathize with Roy Batty, leader of Blade Runner's small cell of outlaw replicants. For Roy, being alive is an offense worthy of capital punishment, so his behavior clashes with society's standard set of laws and ethics. He's a mass murderer ... but the circumstances of his creation and continued existence put him in a kill-or-be-killed default mode. Roy's pretty evil, but it's just like that old Arthur Fleck joke goes — what do you get when you cross a self-aware robot with a society that abandons him and treats him like trash? You get what you flippin' deserve!

Like tears in rain

Harrison Ford is a pretty big deal. He played Han Solo and Indiana Jones. Those two roles alone are enough to transcend the status of mere actor, and they establish Ford as a pop culture institution. And in a major contender for the best scene in Ford's entire generation-spanning career, all he does is lie on the ground and look at Rutger Hauer.

As Blade Runner spirals to its conclusion, Deckard tracks down Roy, and their encounter evolves into a ruthless rooftop scuffle. Following a period of significant destruction and mayhem, Roy decides to spare his enemy's life. With the battle finished, he sits beside an injured and defenseless Deckard and observes, "I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain."

Best. Death. Scene. Ever.

Astoundingly, Hauer conjured up much of Roy's monologue on the spot. According to a 2017 RadioTimes interview, the actor tossed out what he considered excessive verbiage and just focused on the parts he thought suited Roy and the moment. As he explained, "Ridley gave me all the freedom [to ad lib] because he wanted [Blade Runner] to be a character-driven story."

Hauer passed away at the age of 75 in 2019, the same year Blade Runner takes place. We refuse to believe that's a coincidence.