DC Lied To You About Batman

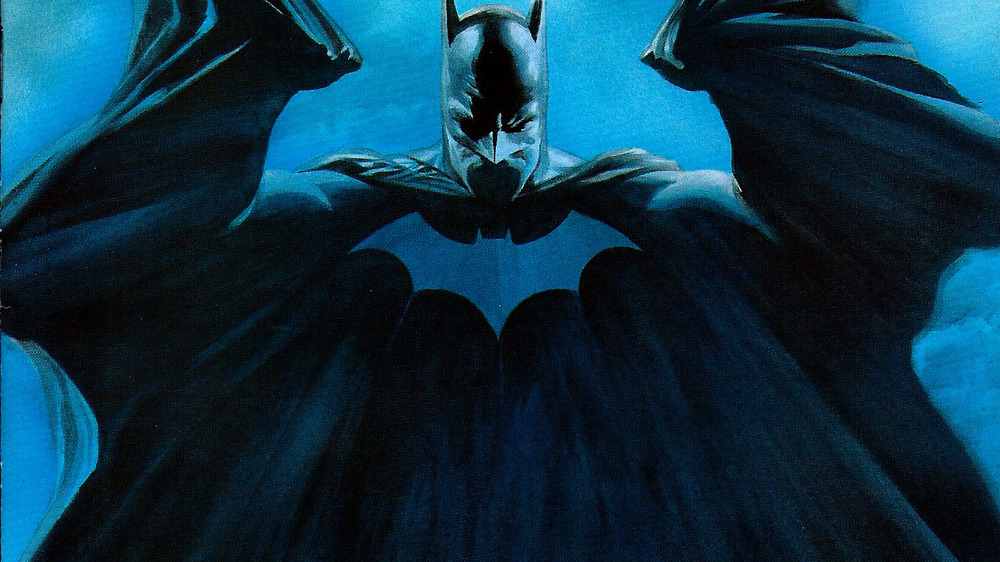

As is the case with his best pal Superman, DC has kept Batman pretty consistent over the decades. Everyone knows his origin story: A murderer killed Bruce Wayne's millionaire parents, so he devotes himself to a war on injustice and suffering. The story goes on in comics, films, TV shows, video games, and so on, for as long as we continue to spend money on Batman-related media. But that doesn't mean Batman has remained static. To the contrary — different creators of different eras making stories for different audiences have all added their own ideas and perspectives to the caped crusader and his mythology. As a result, we have a character who is equally Frank Miller's brutally violent crimefighter from The Dark Knight Returns, and the wholesome Bright Knight portrayed by Adam West on television in the 1960s.

There is not one correct Batman: There are many Batmans (or should we say Batmen?). If a single character is going be the center of more than 80 years of stories, however, he's going to end up enduring some retconning and misleading marketing. Occasionally, DC has ended up outright lying about Batman, through storylines that go nowhere, last-minute reversals, and character details that end up abandoned. Let's take a look at those times fans were misled as to the Dark Knight's motivations, plot arcs, and even his stance on weaponry.

Batman doesn't die in Batman RIP

When DC Comics and Grant Morrison decided to title a storyline "Batman R.I.P.," they had to have known they were entering some pretty loaded territory. The story isn't called anything quite so direct as, say, "The Death of Batman," but you certainly can't blame comics fans who saw "Batman R.I.P." advertised as an upcoming event in 2008 and drew the incorrect conclusion that Bruce Wayne's goose was about to be cooked.

Batman does seemingly die a ridiculous death in comics published right around that time, in fact — but not in "Batman R.I.P." The death occurs in another Grant Morrison comic, entitled Final Crisis, in which a valiant but unsuccessful attack on Darkseid ends with the caped crusader reduced to a smoldering skeleton in Superman's arms. While the image of an anguished Superman cradling the carcass of a fallen ally is powerful, it left fans asking themselves questions, like, "DC doesn't really think we believe they just killed Batman for good, do they?" I mean, come on: It's Batman. But hey, there was "Batman R.I.P.," seemingly nailing the coffin shut.

Turns out, it was up to fans to pay attention to the fine print. "We're not really entertaining the notion that Bruce won't be back at some time," Morrison told Comic Book Resources in 2009. " ... This is an ongoing story, another chapter in the life of Batman." This turned out to be entirely true.

At least one story from the Silver Age turned out to be a hallucination

Grant Morrison's celebrated Batman run, which began in 2006 and ran until 2013, is engrossing, cerebral, and inventive. But compared to most mainstream superhero books, it's not especially easy to follow.

In an especially audacious move, this run involves a hitherto forgotten story from 1963 called "Robin Dies At Dawn!," in which Batman volunteers to play guinea pig in an experiment investigating the effects of isolation and sensory deprivation, overseen by the mysterious Doctor Hurt. According to Morrison's run, while Batman was in that state of heightened mental vulnerability, Hurt implanted "Zur-En-Arrh" as a subconscious trigger word to cause amnesia and confusion and generally render Batman useless. But, two steps ahead as always, Batman created a backup personality that would arise if just such an attack on his mind was ever successful. Hence, the unpredictable and garish Batman of Zur-En-Arrh came to be.

However, the Batman of Zur-En-Arrh first appeared in a 1958 story that depicts him as an extraterrestrial hero entirely separate from the Batman of Earth. It is thus implied by Morrison's comics that the Batman of Zur-Eh-Arrh Bruce Wayne meets off-world is, in fact, an isolation-induced hallucination.

So, if we're understanding all this correctly, this Zur-En-Arrh situation opens the door to the possibility that quite a few wacky sci-fi Batman adventures from the 1950s are simply instances of Bruce indulging in a little Altered States-style sojourn across his own personal dreamscape. Pretty trippy.

Batman doesn't kill people -- most of the time

We're probably not the only ones getting worn out from debating the merits of 2016's Batman V. Superman: Dawn of Justice. But if we must discuss deceptive depictions of the Dark Knight, then there's no getting around the criminals squashed under a marauding Batmobile, torn apart by a bat machine gun, burned with a bat brand, and subsequently murdered in prison. Batman kills a whole heap of folks in BVS, and it's an issue.

We're not saying superheroes all need to behave like upright role models and encourage nonviolent conflict resolution. The Punisher's not the Punisher if he never kills anybody, for example. But Batman's anti-murder stance is fundamental to who he is, and excising it is lying about his character. It's a major point of contention between him and Jason Todd, after the latter returns from the grave. Batman also drills a no-kill edict into Damien Wayne's head. While training with the League of Shadows in 2005's Batman Begins, Bruce Wayne's falling-out with the group occurs when he's ordered to execute a thief. In Injustice: Gods Among Us, the Joker detonates a nuclear bomb in Metropolis, and Batman tries to stop Superman from extracting fatal revenge on him, even under these extreme and arguably justified circumstances.

Those are three unrelated stories in three different mediums that all agree: The no-killing rule isn't just an arbitrary choice, but a defining aspect of who Batman is and how he operates.

Maybe he isn't the world's greatest detective?

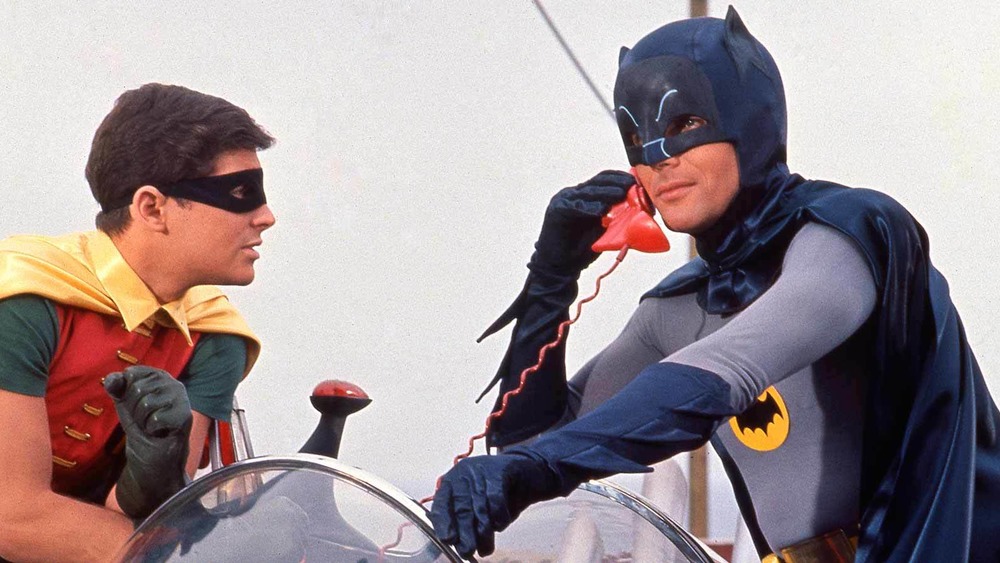

When we think of the 1966 Batman TV series, we think of goofiness. Adam West's version of Batman certainly embraces superhero silliness more brazenly than most iterations of the character, and so to some degree, '60s Batman can get away with looking stupid. The show is a big, bright exception in most fans' minds, after all. But even here, Batman's acceptable level of idiocy has its limits.

The plot of the 1966 Batman spinoff film involves Batman's arch-enemies joining forces and orchestrating a scheme to kidnap ... Bruce Wayne. In order to execute this plan, Catwoman (Lee Meriwether) disguises herself as Russian journalist "Miss Kitka" and sets about seducing Gotham's favorite son. During their various trysts, Catwoman never notices Bruce Wayne and Batman are the same person, and Bruce doesn't connect Miss Kitka to Catwoman until she loses her mask in a fight late in the movie.

In fairness to Selina Kyle, this version of Batman's cowl covers his whole head except for his jaw. Therefore, an intelligent person could conceivably not notice the similarities between Bruce and Batman, especially when encountering the two personas in totally different contexts. But the only thing concealing Catwoman's true identity is a simple domino mask. Catwoman and Miss Kitka are obviously and unmistakably the same person. "World's Greatest Detective?" Apparently not in the 1960s when a feline fatale is on the prowl.

The temporary death of Jason Todd, plus almost all of Batman's other sidekicks

Nowadays, there's no real point in harping on the impermanence of death in superhero comics. If a major character dies, they're probably going to come back — we all know this. A lucky few even have de facto immortality, a la Deadpool, from their healing factors, which makes it simpler for writers to explain how these folks keep managing to die and then resume being alive.

But in 1988, Doctor Who-esque infinite resurrections were not yet an implicitly understood attribute of basically everyone who inhabits the Marvel and DC Universes. Aside from a few characters like Gwen Stacy and Jean Grey, the grim reaper had left the main and supporting casts of both superhero continuities largely alone, because death stuck around. So when DC readers voted to kill Jason Todd, the first replacement as Robin, in "A Death in the Family" by Jim Starlin and Jim Aparo, those readers had every reason to assume he would stay gone.

And stay gone he did, for almost 20 years. Then Judd Winick — formerly known as Judd from MTV's The Real World: San Francisco (1994), an essential touchstone of '90s TV — brought him back as the new Red Hood. But let's not judge Winick too harshly. Seeing as how Batman proteges Damian Wayne, Tim Drake, and Stephanie Brown have also all been killed and brought back in subsequent years, the second Robin's return was pretty much inevitable.

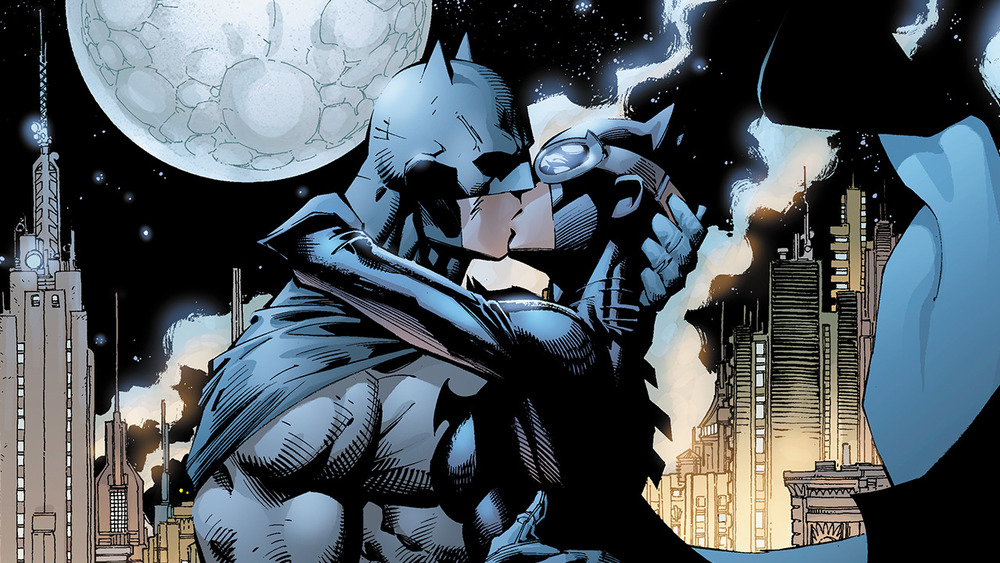

Even Batman and Catwoman can't remember where they first met

It's hard to put an exact number on how many Batman stories have been told over the course of 80-plus years. But let's give it a general estimate and say there are a whole a heckuva lot of Batman stories. As certain aspects of his past have been revisited and reimagined by various writers, details have gotten mixed up and even swapped out for different takes. After a while, this gets confusing ... even for Batman himself.

During writer Tom King's run on Batman, which began in 2016 and ended in 2019, Batman and Catwoman get serious about their storied on-again, off-again romance. Occasionally, while enjoying a cozy moment with each other, they reminisce about how they first met, as couples often do. The problem is, Selina remembers their first meeting as it happened in 1987's Batman: Year One, while Bruce recalls their initial encounter as the one from 1940's Batman #1.

It could be that both stories happened in-continuity. Bruce and Selina haven't nailed down their costumed identities yet when they meet in Year One, whereas Bruce is fully Batman during their encounter in Batman #1. But for that to be true, Bruce has to either forget the Year One meeting, or not recognize Selina during their second meeting on the boat.

It's all a bit tangled, but no matter how you slice it, DC has ended up lying about major aspects of the couple's beginning.

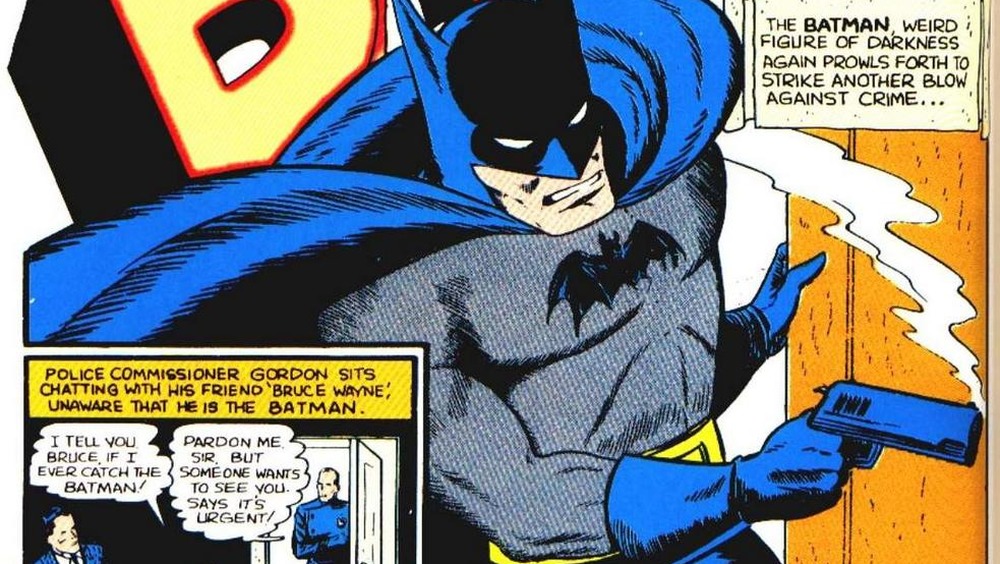

Batman never uses guns ... except in early Batman comics

Some folks like to push back against the idea that Batman doesn't kill. When they do, they point at Dark Knight Returns, because of a famous scene in which Batman shoots a member of a mutant gang in the shoulder. He also declares guns loud, clumsy, and stupid, and "the weapon of the enemy" in DKR, but that's a matter for an entirely different article. The pro-Batman-murder people might also point to extremely early renditions of the Dark Knight, back when co-creator Bob Kane was still putting his name on the comics. In these issues, he is indeed occasionally shown with a gun.

Yet even in these instances, Batman is never Frank Castle or Wade Wilson. The entire superhero genre was testing the proverbial waters at the time these comics were published, and still figuring out what the standard "rules" would be. Thus, Batman progressed from being an occasional gun user with some degree of ambivalence towards the continued living of his adversaries to a strictly bullet-free crime prevention and discouragement figure. One comics scholar argues that a panel in Batman #1 inspired editors to establish Batman's anti-death approach: In it, the superhero starts a sentence with the phrase, "Much as I hate to take human life ... " before taking some human life. Is it confusing? Yeah. Does it mean DC has lied about Batman and guns? Also yeah. Oops.

Terry McGinnis's father isn't who Batman Beyond says he is

1999 was a pretty long time ago, so not everybody clearly remembers Batman Beyond, the sci-fi-infused animated series that introduced a brand new Batman to the world. The cartoon follows Terry McGinnis (Will Friedle), a high school student living in the Gotham City of the near future. Following the violent demise of his father, he becomes a protégé of the now-elderly Bruce Wayne (Kevin Conroy) and assumes the mantle of the Batman for his era.

Batman Beyond ran for three seasons, with 52 total episodes and a movie. But fans didn't find out the whole truth about Terry's parentage until years later — and on an entirely different show, no less. In a 2005 episode of Justice League Unlimited entitled "Epilogue," Terry McGinnis learns he's actually the result of a complicated plot perpetrated by Amanda Waller. The one-time head of CADMUS had concluded that the world requires a Batman, ergo, she needed to engineer a replacement for the aging Bruce Wayne. Cue a complex scheme involving genetic overwriting of Terry's dad's DNA with Bruce Wayne's, via fake flu shot.

So, Terry McGinnis' father's death did not technically inspire him to become Batman — It was actually the death of his mom's husband that did that. Bruce Wayne certainly became a father figure in McGinnis' life, but boy, neither of them, nor the fans, expected it to be so literal.

Bane hardly appears in Batman: City of Bane

At this point, it's difficult to tell whether Tom King's tenure on Batman is genuinely polarizing, or if every Batman writer gets a bunch of extreme reactions. But starting from roughly the second arc of his run, King started playing with fire when he deployed Bane as a master manipulator, arranging events and people to engineer Batman's undoing.

Once the reader arrives at the finale arc, "City of Bane," they see plenty of the Flashpoint reality's version of Thomas Wayne, who is a big jerk. City of Bane also features oodles of Bruce and Selina repairing their seemingly annihilated romantic relationship. But there's not a whole lot of Bane in "City of Bane." The world's most infamous product of the Santa Priscan prison system functions as a secondary villain, or, to indulge in a video game metaphor, a mini-boss. But his name is right in the title. What gives, DC? Why lie about his presence — or lack thereof?

An explanation has been offered: "Bane is the name of the supervillain, but 'bane' also means 'you're the bane of my existence,'" King told EW. "Bane is also the feeling, the motivation of Thomas Wayne. That was supposed to be a pun and no one noticed because it turns into the city of Thomas' bane."

All of that technically holds true. Also, we suppose "City of Thomas Wayne, Who is Batman from Another Dimension" would've looked clunky.

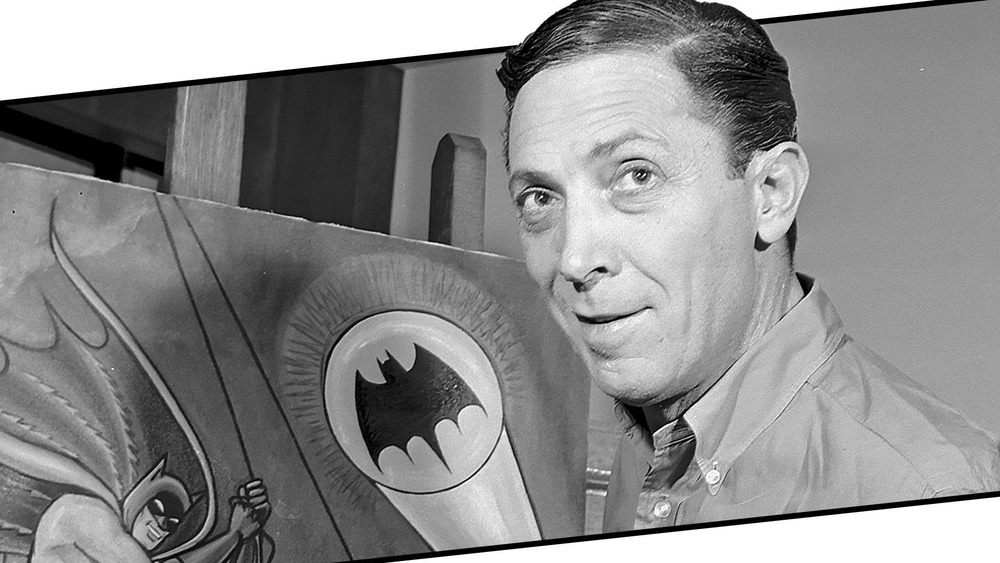

DC took a long time to credit Batman's hidden creator

During his life, Stan Lee took a tremendous amount of flak for, in the estimation of some, taking credit for the work of Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and others. Whether the likes of Kirby and Ditko were financially compensated sufficiently is one matter, but in terms of sheer props and pats on the back, Stan Lee generally gave Kirby and Ditko their due. Savvy fans today know that they, and other creative talents, deserve just as much credit for the creative explosion Marvel underwent during the 1960s as Lee did.

In other words, Stan Lee was never a grifter on anywhere near the same level as Bob Kane.

As has been pretty much public knowledge for a while (it also gets spelled out in the excellent documentary Batman and Bill), Bob Kane came up with the name "The Bat-Man" .... and that was about the extent of his contribution. Essentially, all the other elements that make Batman Batman actually came from writer Bill Finger, who DC did not acknowledge as a Batman co-creator until 2015, decades after he died in obscurity in 1974. Kane flagrantly claimed credit regardless, along with no small amount of money.

And so, ironically, we partially owe the existence of one of popular culture's greatest fantasy heroes to an inveterate scam artist. Go figure. Batman wouldn't be too happy about that, but hey, what's a superhero without a dark origin story?