Director Angel Manuel Soto Talks Charm City Kings, Will Smith, And More - Exclusive Interview

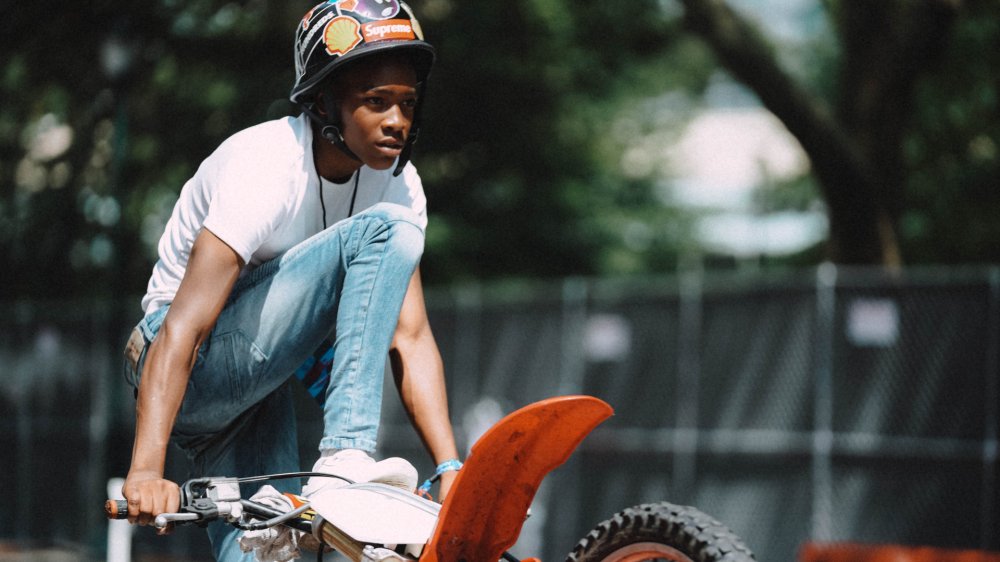

Angel Manuel Soto is making a name for himself in Hollywood with his latest film, Charm City Kings — produced by Will and Jada Pinkett Smith's production company, Overbrook Entertainment. The movie follows Baltimore teenager Mouse as he's torn between his dreams of becoming a vet and his desire to join the dirt bike gang Midnight Clique. Growing up in Puerto Rico, the director found personal resonance in the film's subject of racial inequality and toxic masculinity, and he used his own experiences to connect with the material. Soto has written and directed a number of Spanish films, short films, and short documentaries like Inside Trump's America and La Granja (translated to The Farm).

Given that it was inspired by Lotfy Nathan's 12 O'clock Boys documentary about Baltimore dirt bikers and their culture, it was important for Soto to keep the film as realistic as possible. Instead of hiring a slew of actors to fill the extra roles, the director made sure to include many of the real riders depicted in the documentary, giving them a voice in the movie — and it shows. Since its release, the HBO Max film has received a high level of praise from critics and fans alike.

Looper spoke to Soto to talk about all things Charm City Kings, Will Smith, Meek Mill, and the important social issues tackled in the film.

Will Smith and wheelie wonk

What was it like working with Will Smith and Jada Pinkett Smith as producers and how much of their vision and input did they lend to the project?

Working with Jada and Will was very, I mean, besides being super surreal, I [went] from Puerto Rico, working with talents he has seen since little shows that have been done in Spanish. It's crazy, but being able to see them trust [in] the creative choices and the people they hired for the job was something very encouraging. They ran with the vision that I had from the beginning, and they let us really take control of the ship and steer, do our own thing. By saying us, I mean me, myself, the VP and Caleeb, who's Jada's brother and the producer, and Clarence. They were very respectful. [They gave us] the space, and throughout the production, they pretty much let us be towards the end. [In] the end, they went into more on the post-production and just toning a [few] things to their perception. But I guess if I can define my experience with them [it would be] undivided support. I think that's the best way to describe them as producers.

That's fantastic. What aspects from Lotfy Nathan's 12 O'clock Boys documentary did you want to shine most through the film, and what were you most excited to put your own spin on?

The documentary was really a starting point. I remember when I saw the documentary first, I loved it [because of] the way that it [depicted a subculture] that I had never seen before living in Puerto Rico. And having documentaries and movies as windows to the world, it was definitely alluring. We have a little bit [of biking back at home], but the way they talk about it and the way they react to it and how talented they are, it's something that really caught my attention — that sense of freedom that they feel when they're doing that. And how the amount of balance and discipline and talent that you have to [have] on a professional level because they are very professional in what they do, definitely was something alluring. And when it came to the script, I really appreciated that it tried to stay true to the backdrop that this culture creates and how it enriches the city of Baltimore as its own powerful thing.

So being able to keep that myth or legacy or sense of community and freedom and happiness that you get from the desires of Pug in the movie and the other characters, we wanted to keep that as part of the heart of our main character, which is inspired [by] Pug, and be able also to have the community that you see take part in the documentary, be an essential part of [of the film]. Not extras, but even like the supporting cast of the film. So we really, we refused the idea of not using the real people from the documentary in this drama. That's inspired [by] real events, not really based on those just it inspired the energy and the world-building that the documentary had.

Definitely. Did you get on a bike yourself? Did anyone teach you some tricks?

Yes, actually, I did, but it was towards the end. I didn't dare to do it before or in between shows. We spent a lot of time going to the rides with them and taking us to different parts where they would practice their tricks. But towards the end, I think I stayed a couple of days, and that's when I went, I got on a quad, and I tried to pop a wheelie, and it's not as scary as I thought it would be, but still to have that amount of craft that they do — [to] do [a] wheelie and stand on the seat and tap dance your way for... I mean, it's impressive. Like what I saw, there was an amazing amount of talent from brilliant artists that have been built by society.

Were you successful in your wheelie?

No. [Laughs] It was more like a wonk.

So like on a skateboard except higher. [Laughs]

Exactly. The quad is a little bit... I asked them [if it was] easier [on] that, on that bike, but with my luck on my balance, I don't know if I would have lasted more than five seconds.

The power of authenticity

This is such an important story to tell, especially in the current climate. What were the most important things that you wanted to get across while telling the story of these young Black men and the challenges they face?

Well, I mean, one of the things that I love about this story is that as a coming of age drama, [there are] certain tropes that are part of it. They come with the territory and being able to use that vehicle, that means of transportation, in order to tell a story that really explores the struggles and the journeys of being a marginalized kid in a disenfranchised neighborhood.

I felt that the power behind this story was being able to stay authentic to a reality, that coming from Puerto Rico, I saw a lot of myself in Mouse and what Mouse goes through. In this story and [how] all the different elements and obstacles that the city of Baltimore, as a marginalized community, has, is very much the same as the one that Puerto Rico has. So a lot of the things and situations and journeys that Mouse went through, the loss of friends, the way Mouse had them, are very keen to my own experience or experience of people that I grew up with.

So [we were] able to tell a story of marginalized communities by people who have been a product of marginalized communities with people who are very proud of them putting these communities in front of the camera. I think that paves the way in terms of not only representation, but being able to own our own stories and being able to not separate us from all other communities, but find the intersectionality between us.

Embracing the opportunity for change

And that's why I like the whole power that comes within the communities of black and brown people when they come together and share their own experiences and are able to tell stories that we want to tell regarding our own experiences and with them be able to talk about topics using that vehicle of a coming of age drama that resonates with the struggles that are rarely talked [about]. Communities like ours, for example, the deconstruction of toxic masculinity, and the fact that a lot of the bad decisions that we as men will opt to make are founded in the false concept of what a man is supposed to be.

And we're taught that "men don't behave that way." "Men don't cry." "This is what a man is supposed to do." And all that pressure growing up really builds into a distortion of what a man is supposed to be. So having that kind of be a subtextual element throughout really helps navigate the other aspects of family, of [the] pursuit of happiness, of mentorship — which is something that a lot of our communities struggle with and the right role models to follow in order to foster our full potential. So with all that said, that's [the thing I really gravitated to the most] when I was working on the film, because I was like, "I want to do a film that I wish I saw when I was a kid." I want to see a film that, [in] the end, I feel like, "Okay, maybe I do have a chance."

Maybe I do have an opportunity. And I was one of the lucky few to have a father there who, even though he spent a lot of his time working and I rarely [saw] him, he served also as a mentor that allowed me to stay away from the streets. Even though I lived in the streets and all my friends were a part of it, I didn't partake [in] it — thanks to that limited amount of love that I had. So being able to communicate that to the future generation and see how they can start a conversation after watching a film like this in order to create change within the community on themselves, I think that will be my biggest takeaway from it if anybody is willing to see that.

Ditching toxic masculinity

Love that you brought up toxic masculinity because one of the most impactful moments from the film is that scene when Mouse is just sobbing on his mom. It's so important and so powerful to show boys that it is okay, that you have these reactions, that's healthy. That's good. So that was really fantastic.

I agree. Well, [that] point for me was powerful because growing up, you don't see that. Or if you see people, kids crying, they usually [didn't look like me]. Almost as if vulnerability was reserved to a particular race. We had to be tough. We had to be rough. We always have to go out and get bread. We always have to do all this stuff. And it's kind of, it's exhausting when you roll up and have all these expectations — and being able to [have] those moments and work with Jahi and this amazing talent that really [understands] and shares the message that I really wanted to tell in this subtextual manner.

I've seen Mouse cry like that. It is exactly what I want people to see. I want people to start seeing [these] coming of age or crime sagas and see those gangsters be vulnerable — see people be human. And I think that this is kind of the start of exploring this anti-machismo type of film, which you can still go and you can carry with the whole access and all the other stuff that crime dramas or coming of age movies come with, but tap into the humanity of a community that's constantly being expected to act a certain way.

Honoring origins: fusing Indie with Hollywood

You sort of touched on this already, but did any of your own experiences as a Puerto Rican filmmaker inform the direction of the film?

Yes. 100 percent. I came in from being forced to do a lot with little and being economical and being resourceful. And that started to inform my visual language in a more inspired, more like Italian Neorealism and movies from all [of these] hyper-realistic films that you can see that come a lot from Europe. And when [you] transition to a film like this which had chase sequences and bikes and stunts and coming of age drama, that was very, it has its by-the-book kind of structure. I'm being able to marry both things with the opportunity of working on a bigger budget that allowed me to play with certain toys, like the car or the bikes and all these other elements. It was kind of like, "Oh, now I can [fuse] the two things that are usually polarized in cinema, like the whole indie vibe and then hyper Hollywood flair and be able to find a middle ground" so that I can feel connected into being able to portray the energy thrill ride I grew up with watching films.

To mention, not that this looks like it, but Indiana Jones and Star Wars and Scorsese, you grew up watching [these types] of movies and then halfway [through] high school, you start experimenting on mobile art, then all these other films from Europe. And that's where I felt I connected the most tonally and structurally because I thought, when will I ever be able to make a movie that I can play with all these stories. Doing Charm City Kings for me is a dream come true. Because I never thought I [would] ever be able to have that opportunity. So given the chance and with the right team with Kate, Scott, Katelin Arizmendi as the DP, Scott of the production designer, Stewie on the Steadicam, all of us coming together and be able to develop this type of narrative. I feel like those sensibilities coming together from multiple artists were able to form a mutual language that resonates to where I am right now.

Rising stars

You were working with an incredible group of young rising talent in the film. What were you looking for in casting, and how did it help your vision?

So when I cast in any particular role, I usually go for the eyes. I usually go for the resting face as a mirror to the soul. Really, if you see somebody just by themselves sitting down, [it] kind of already gives you the character. I think that, in my perception, the battle is halfway won, for me. Then it's a matter of seeing the chemistry, of seeing the range of emotions and that's when it starts to get trickier. Because with a film this big, there are different pressures and expectations. So being able to marry local talent who are riders, who are not professional actors, and marry them with seasoned actors, I think it goes to the other pursuit that I have — which is authenticity and [being] able to keep it as authentic as it is now.

Nobody speaks the same way. Everybody has a different accent, even though there are different words that are typical. So Baltimore having a unique accent in and of itself and being able to have the character of Mouse, what he embodied at first, and then the other ten percent is the actors' work of going out of their way and finding [out] what are the nuances that people from Baltimore [have]? What are the specific words that they have a unique accent [on]? And I think they did a good job of being responsible [for] representing them as much as they could within the outside demeanor, but inside, they were really carried by [this] constant protection of the humanity of our characters, and I'm portraying the humanity of the people in Baltimore appropriately. So yeah, being embedded in the culture as much as possible and being able to see how these kids [and] their chemistry worked from the moment they met. It played before our eyes. We just found them. You cannot fake this chemistry. And they didn't. And they were brilliant.

The Meek Mill and Will Smith origin story

They're awesome. So there's a bit of a parallel between Will Smith and Meek Mill going from rapper to actor. Did you notice any similarities between the two?

I don't know, to be honest. I guess what I know is that they had a lot of conversations. I know that Meek had just come out of prison and he was getting into the character after that whole process. I know he and Will [had] a lot of conversations, precisely because of that. A rapper who's acting [has to be able] to have a work-life balance and do the singing when he wants to, and still be successful. And definitely, Meek has [wanted] to jump into the acting game for a bit. And having this be an opportunity of playing an actor who [very] much is him, except that in the movie, he's a mechanic in real life and Meek is a rapper, but everything else is very much representative of Meek, [and] who he is as a person.

And him finding in this character a way to play a better version of himself, if that makes sense, of being able to really be himself and yet tell the version of himself he wants people to follow from now on. And I think doing so, definitely, he had a lot of help from Will Smith. I'm sure his journey was an inspiration. Also, Louis Stancil, an acting coach, spent a lot of time with him, making sure he went over the [lines and] learned the body language. And he started loosening up. It was really awesome to see him from the first day he came to set, and when we left, how he owned that character, how he embodied that character. How he even pushed himself to deliver the best performance he could.

Writers and blocking

You've done some writing in addition to directing. How has being on both ends of the production informed how you approach each role?

So I've been used to writing a lot of the stuff that I have shot. And this one was my first big project that I directed where I didn't write the script — and it took me a little bit of time to understand that I don't have full control. This is a movie that you are directing. It is your movie, but it's not your movie. You know what I mean? I'm like, "Okay, okay. I'm understanding." I was so used to having to do everything out of necessity in Puerto Rico with friends, and everything's kind of like [looser] in a way. The DP or the camera operator is shooting something. I like something? I can just take the camera and shoot it. Here's different, with the union rules and the way that things are navigated.

And it took me just a little bit of time to understand that, but once it went through and once the outcome came out, thankfully, I think for the most part to the fact that I was working with an amazing team of artists and collaborators that made [the experience] so gratifying and memorable. I still write. I like to write. I write a lot of what I feel, or even if it's commission, I'll compare. It is a very lonely and gut-wrenching experience, but I like to be by myself a lot. So that kind of like helps a little bit — writing.

But being able to jump into a project and collaborate with a creator and [being] able to take the blueprint and elevate it and get them excited also for me to be able to continue their work after the script is done, was very fulfilling. It's something that I'm looking forward to, hopefully, do forever. It was one of those things. It was family, not understanding that every project is a family forum and a bond you make, you go to war together with these people, and you come out stronger (or not). But in my case, my experience has been very good. I hope there are more like that because I intend to keep directing stuff for other people. I really enjoyed it.

Major props and tour guides

What was it like working with Oscar-winner Barry Jenkins?

Well, Barry, I met him New Year's this year. I didn't get the chance to work with him because when he developed the first draft of the film, this was way before I came into the project. And he left the writing and directing of this film to do Moonlight. And I'm thankful for that because he's definitely... he has a career that I hope I can emulate in some way. And I was able to do the film that he started to write, but Sherman Payne was the one who took the rewriting service based on the backbones that Barry Jenkins laid out and the structure, Sherman was able to really bring his own thing and build up on top of that and create his own voice to tell the story he wanted to tell.

And it wasn't [until], like I said, after the film was edited and done prior to his premiere, that I met Barry Jenkins and we hung out in Puerto Rico for a little bit. I was their tour guide. It was Barry and Lulu, and I was their tour guide almost for the whole week. And it was... he's [on] my Island, I wanted him to have a great time. I love my Island. So I wanted him to enjoy it and have a memorable moment until the conversations that we had. It was really humbling and exciting to hear that he was happy that he was thankful that [I] took the work. And he was very proud of what came out. So I guess my experience with Barry has been very positive.

Riding the Sunday ride

Those are some pretty good props. Do you have a favorite scene or a scene that you think is the most powerful?

I think I've got two things that are my [favorites]. My favorite scene was the Sunday ride scene — when Mouse goes to this Sunday ride first, and the camera drifts into this corner, and you see the complexities of the choreography. And I liked that scene a lot because what I tried to do there was because the film is really on Mouse the whole time. It's really focused on him. He's almost in every frame of the movie, but when the camera group stuff, it's those moments that I do on purpose to be like, "Okay, audience, this is [you and me]." And I want you to see what I saw, the way that I experienced it when I first walked into one because it was so impactful. And most of the people that are going to watch the movie have never been to a Sunday ride.

So I was like, "I need to make them feel the way I felt." And that's why that scene for me was very powerful. The other one is when his bike is stolen that it's all one shot. The guy goes, and he loses the bike. And that also happens to be Barry's favorite scene. So when he hints that that scene blew him away, I was like, "Oh, that's awesome." Because when we were there, I was like, "This needs to feel like it just happened before you." I didn't want to cut on that scene. I [wanted to make it feel] in real time. How can you get from fear to despair, to stray, all in real time and being able to pull it off with the help of, not the help, with the amazing performance of the actors over there, on those scenes of the stunts and all those things?

But also, the score of Alec Summers really helps to underline that emotional roller coaster that Mouse is going on. So I think those two things are my favorite. I think they were the most complex in terms of doing it safely. And the other one when they steal [the bike]. We had a window because of that specific light we wanted to use. Where it's not dark yet, but it's dusk, I think — that dusk light. So we will have five minutes to do that scene. So we only did two takes. That's all we had, two takes. And the second one, it was perfect.

There were a lot of those things — we only have two takes to do this. [For one] well, we have five hours, five hours to pull this off. Three of them are for rehearsal. So good luck. [Laughs]

Expectations vs. reality

Things that people would never think about when they're watching the film, those kinds of restrictions.

The thing here is, you want to give restrictions. This was another [new one] for me because I wasn't used to that. I didn't know that with kids, you don't have that much time to work with [them].

And not only that, they tell you it's nine hours. I'm like, okay, you can work with nine hours. But because it was shooting during the fall, it's nine hours minus three of school and minus one of lunch. So you really have the kids for five hours.

So the expectations of being able to work with them for 12 reduces to less than half. And you're like, "Okay, now we really have to make everything work." But we were lucky. I mean, not lucky. We were blessed to have a slew of talent that was so dedicated and professional and really carried like the actor ethics and the guys that were not actors. They really stepped it up. They went out of their way to achieve what we wanted and being able to have them and the community around telling us kind of, we don't say it that way, or we say it differently or no, we don't... it did help.

And every scene has the hand of somebody in the [biking] community with an opinion. And I think that's in a very respectful and helpful way. For example, we thought Willie Wayne, who is the leader of that pack in 12 O'clock Boys, he was the one that really made it happen. He was the one that, more than his blessing, he was the one that was able to call the community to be a part of it. He was the one that selected the riders. All the riders on the Midnight Clique, they are from the documentary 12 O'clock Boys. So it's like having them there.... it's a movie, it's a documentary. So being able to keep it as grounded as possible without going all out on the side of just casting, not actors, it's a healthy balance of professional talent and artists.

Get ready to go out and buy a dirt bike (and a first aid kit), because Charm City Kings is available on HBO Max now.