The Real Reason They Don't Make Beach Party Movies Anymore

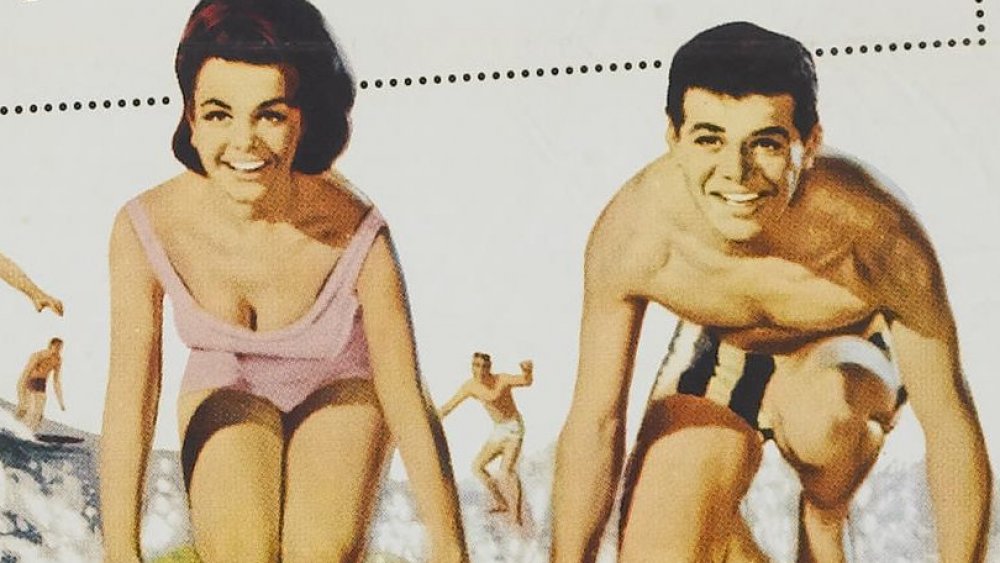

Beach. Party. Movie. Sounds like three of everyone's favorite things, right? From about 1963 to 1967, audiences really were enchanted by that trinity. The "beach party movie" was as much invented as it was stumbled upon, when American International Pictures released Beach Party and surprised everyone with one of the blockbusters of the 1963 summer. This cheerful ode to fun in the sun is built around an ironclad formula: Stodgy adults versus teens who just want to dive, literally and figuratively, into endless diversion. Having found success with Beach Party, AIP distilled the cinematic formula of the subgenre and applied it six more times, inspiring other studios to follow suit. A slew of beach party movies ensued, featuring teens, bikinis, and a whole lot of good, clean fun.

Beach party films were truly a universe of their own, one that defied many cinematic conventions. But nothing lasts forever. Nearly as soon as the genre exploded, it was over. Were there too many cooks in the kitchen — or, perhaps, barbecues at the beach? Was the formula for success not as flawless as studios initially thought? Was it all just a crazy stroke of luck? We're here to explore the rise and fall of the beach party movie, from its sandy weightlifters to its doe-eyed bikini babes.

The zeitgeist problem

The rock-solid formula of the beach party movie is all about appealing to teens in search of simple, sun-kissed pleasures. The characters in these films just want the freedom to enjoy a day at the beach with bare-skinned, one-dimensional love interests, against a backdrop of of swinging '60s music. But for all this focus on the youth market, these movies often employed actors who were past their prime. These were actors on the other side of notoriety's double-edged sword: They'd been the stars of their day's white-hot genres, but that had been a long time ago. Examples include Buster Keaton and Boris Karloff, a king of the silent era's physical comedies and an icon of horror film, respectively.

The divide between the giggly teens partying on the sand and the gray-faced adults is very much enhanced by the presence of such venerable actors. Their eminence is part of the genre formula: For as much as the teens depicted in these films shun grown-up expectations in favor of fun, rigid adherence to expectation is the entire foundation of the genre. Casting actors like Keaton and Karloff evokes the audience's boring parents, but it also cements just how traditional these movies are. That worked for a while, but it also had its own problems. Teens didn't know or care about the faces of yesteryear, and yet there they were, cluttering up movies made especially for them.

A surfer's dozen

No fewer than 12 beach party movies were released in 1965 alone. This was the year the beach party movie peaked: There was no following such a streak. Whatever success 1963's original Beach Party possessed, the genre was no match for supply and demand. Specifically, there ended up being an absolute avalanche of supply, and a level of demand that was quickly exhausted.

From the beginning, the beach party genre refused to be topped, even by its own lineage. The formula Beach Party discovered was ideal, and so the summit of the genre was immediately reached. What followed was insurmountable market saturation. The sheer volume of these films was enough to exhaust creators and consumers alike for good. Competition can be great fuel for creativity, of course. But studios went into such a frenzy of making these films that at some point, competitors effectively canceled each other out. When the competition fizzled, the genre followed soon after.

Serial kills

Beach party films made by studios other than AIP were not necessarily sequential. AIP, on the other hand, connected the bulk of their 12 films loosely through shared universes and recurring characters. It was sort of like the MCU, but with flirting instead of combat and a whole lot more surfing.

Perhaps if these films had had a plot, this serial construction would have made more sense. But their lack of substance meant that the genre couldn't depend on the allure of in-depth plots and character investment as a through-line to tie the series together. By forcing subsequent films to assume sequel status, AIP imposed an immense amount of pressure on audiences and filmmakers within the beach party universe. But there was, of course, not much substance to work with. With little to develop, the studio developed the formula instead, adding increasingly ridiculous elements to a genre that had already reached maximum utility.

Absence of deep characters and drama is what made the first film so easy to watch, and thus to sell. But the concept didn't have the legs to go further. The genre shouldn't have been forced into a sequential structure, and likely would have done better if each film had been allowed to be more random, and have a mind (or mindlessness) of its own.

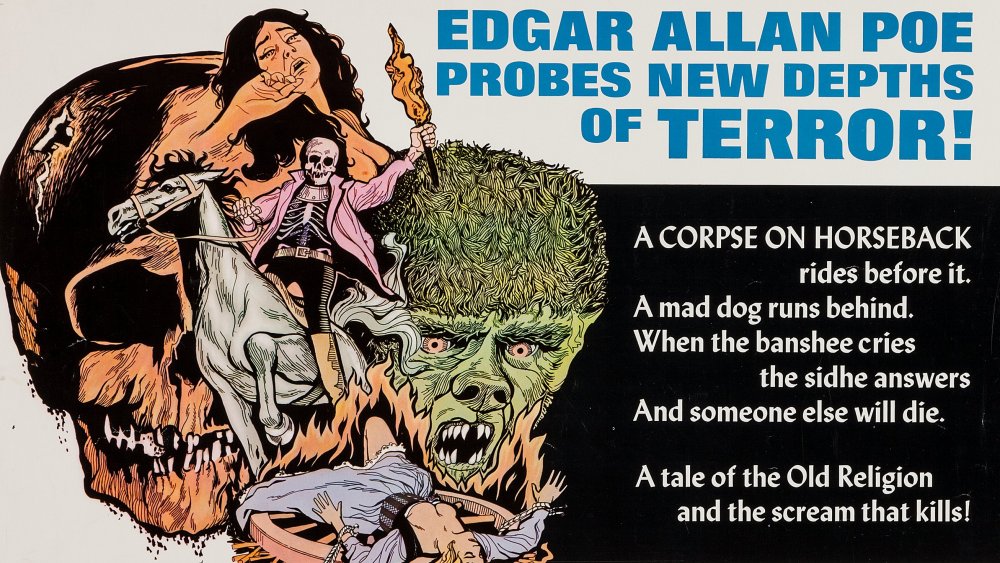

Hip music becomes a problem

The beach party films in the AIP series had musical continuity, in addition to continuity of cast and context. Nearly all of the films released by this studio were scored by Les Baxter, who trafficked primarily in the horror and beach party genres. He went on to score music for theme parks like SeaWorld and a whole lot of movies about dangerous young women in leather miniskirts. Baxter's music pairs well with spectacle, meaning it worked as well for Bikini Beach as Cry of the Banshee. The formula for the beach party movie is a lot more closely related to the horror genre than it may appear — nightmares, after all, are very close to just being dreams.

But the exotic soundtrack style Baxter pioneered also contributed to the damningly self-contained world of the beach party movie. Because the films have such a specific vibe, evident in everything from their fashion to their music, they put an expiration date on themselves. They were simply too niche and of-the-moment for versatility and longevity, and the tunes were part of the problem.

Abandonment issues

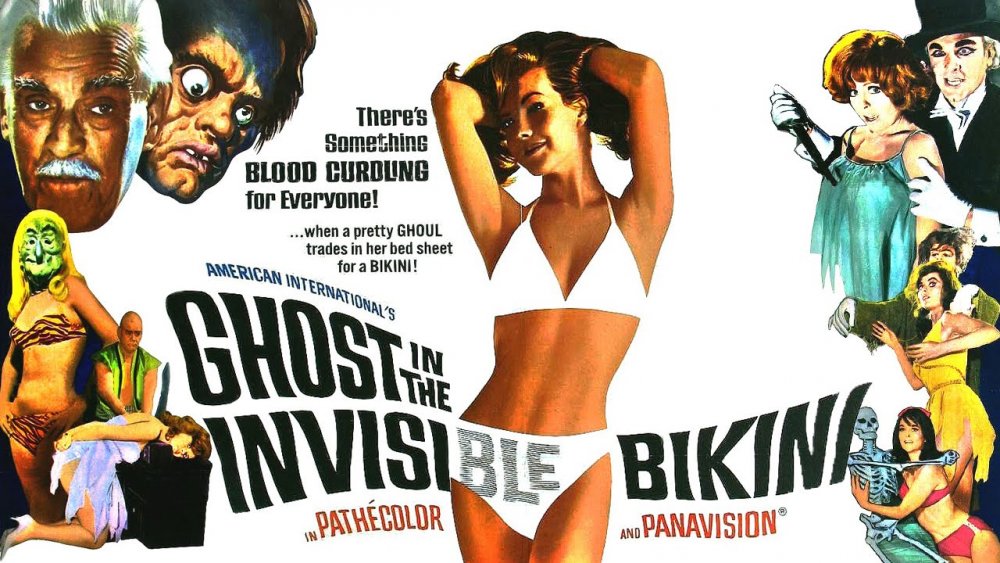

AIP abandoned the beach party movie after making their 1966 flop, Ghost in the Invisible Bikini. At that point, though, the genre had just about abandoned itself. Seriously, there's not even a beach in this final film. Perhaps it's invisible too, although there is a haunted house with a pool where most of the "action" takes place, ensuring the integral status of scanty costumes is preserved.

After this box office bomb, the studio immediately switched to a different fad, and then another. First came stock car racing, then outlaw biker films — yet more visual spectacle, in other words. This is the danger of riding a fad to begin with, even if it's one you created. In the modern world, we often hear that one of the predominant ailments of our time is our truncated cultural attention span. But cycling through fads is one of the traditions we've doggedly stuck with. The failure of the beach party movie might not be evidence of AIP's own failure, in that sense, but proof of the opposite: Their ability to adapt demonstrates market acumen (of sorts), if not artistic prowess. AIP abandoned the beach party movie, and in so doing, built a future for themselves.

Success: The gift that keeps on giving?

AIP's greatest strength clearly lay in visually dominant, dramatically sparse content. Its other great strength was its ability to put its best foot forward — and then the next foot, and the next foot, as a fickle public demanded ever more variety. This latter strength is highlighted by the fact that AIP actually succeeded fairly well in the genres they chose after the beach party movie blitz. This success ensured, however, that there was no reason to backtrack to the beach party movie again.

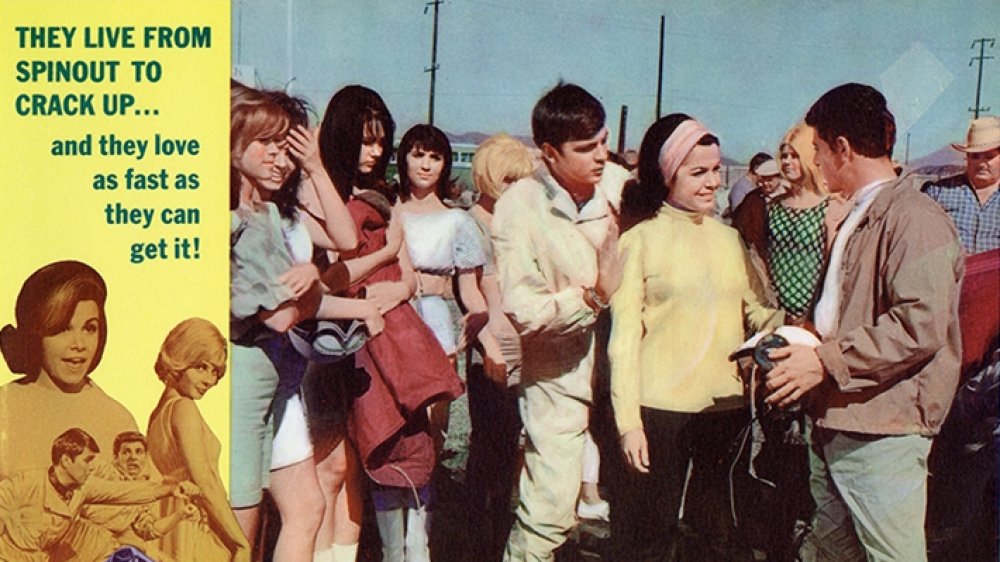

The stock car racing fad was peaking at the time of Ghost in the Invisible Bikini's fateful 1966 failure, and AIP jumped on it immediately. Their first foray into this new genre was Fireball 500, a fusion of the stock car racing film style with the verve of its abandoned, beach-bound genre predecessor. Fireball 500 even featured some of the same stars as the beach party series, most notably Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello, a duo ostensibly synonymous with the sandy genre. Just like their studio, they managed to move on.

The sanctity of nostalgia

The beach party movie is a snapshot of a very specific time in youth culture, and thus built for nostalgia. Moreover, being aimed entirely at adolescents, the genre ended up symbolizing an entire generation's youth. Ah, to be a teen again, attending a beach party — or at least watching a movie about one. Beach party movies are the definition of "You had to be there," and if you were, in fact, there, their memory is sacred.

Today, making more of these films might tap into that nostalgia in an initially endearing way ... but it would also destroy it. Nostalgia is built on wistfulness, a longing for something you can't have anymore, except in memory. The problem doesn't lie in a modern reproduction's ability to do justice to the 1960s originals — even the back half of that original slew had trouble doing justice to its predecessors. The problem is that a modern iteration would mar the very memory it pays homage to.

Putting the "temporary" in "contemporary"

The beach party genre depended heavily on contemporary singers, surfers, actors, and comedians. Often enough, they got it right. Miki Dora, who would eventually become a famous surfer, was featured in the beach party series as a stunt surfer and occasional extra. Actors like Nancy Sinatra appeared not only in the AIP films, but in some of the installments of their competition. The inclusion of contemporary comedians like Morey Amsterdam and Don Rickles was a big part of this up-to-the-moment ethos as well.

But sustaining a high dependence on hot talent is difficult, and can quickly get redundant — Don Rickles appeared in four films in a row. Moreover, a lot of it is guesswork that turns out to be wrong. This genre had to constantly anticipate what the pop culture landscape would look like by the time of the film's release, and pop culture is nothing if not fickle. For every trend the studios managed to capture, there were more that escaped them. Letting teens lead your creative decisions can bring big paydays, but it can also mean being "out" a scant few years after you were "in."

No going back

Paramount Pictures tried to revive the genre with 1987's Back to the Beach, which stars many of the genre's most beloved actors. Unfortunately, it failed to bring in the beach-going bucks. Cynically, this defeat could be viewed as a mercy killing of a genre long past its prime. But in fact, this movie is good. Roger Ebert loved it, and its satirical look at the genre holds up. It's a parody that's meant to be a parody, versus the later beach party movies that ended up as accidental caricatures of themselves.

Any attempts at spin-offs or returns to this genre haven't managed, or wished, to stray from parody: Insomuch as the beach party movie still exists, it's parodies all the way down, a la 2001's Wet Hot American Summer and 2013's Teen Beach Movie. The latter, a Disney Channel Original, makes its satire clear with its name, which allows it to retain a certain degree of sincerity at its core. It was even dedicated to Annette Funicello, the original beach party queen, who had passed away by the time of its release.

While parody and homage are sentimental and sweet, they don't constitute a return to the genre. And that's for the best.

Heavy-handedness

Formulaic marketing to teens tends to be more subtle nowadays. Movies aimed squarely at adolescents definitely still exist, but they're a bit more understated, and actually tend to have something to say. Consider modern genres like young-adult dystopias and superhero movies. They have distinct cinematic appeal, without being unforgivably niche. And while they might still be formulaic, these universes are built to expand: Katniss Everdeen goes down the rabbit hole of corruption and revolution, while Captain Marvel and the Guardians of the Galaxy have taken the MCU heroes to the stars. Moreover, these movies teach young audiences to think critically about the intricacies of their own lives. These heroes face moral dilemmas and questions of justice, power, and revenge.

Compared to beach party movies, today's teen entertainment is practically Kafka. These movies take on heavy issues with a light-enough-for-teens touch, and thus ensure a longevity denied the denizens of Beach Blanket Bingo.

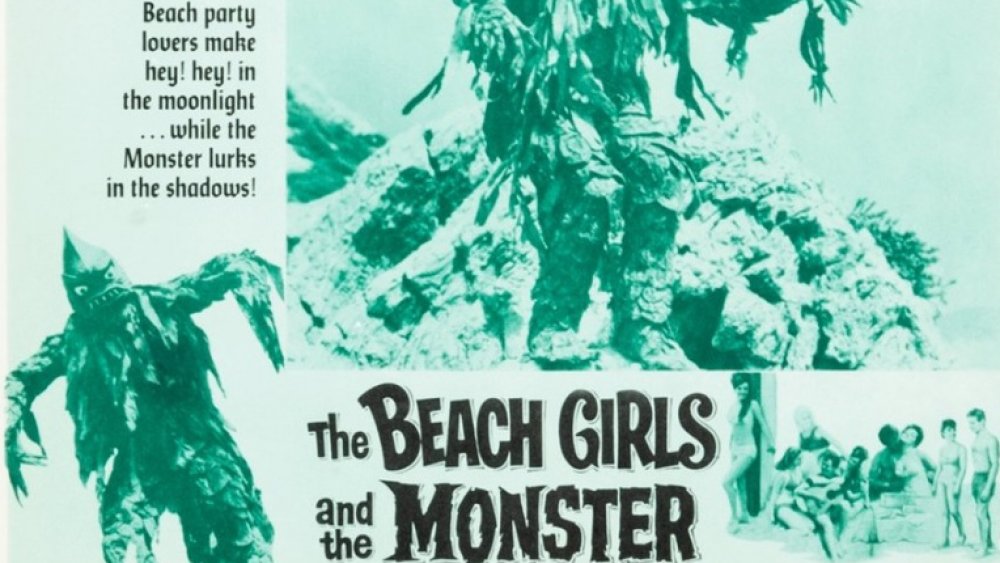

The villainy escalated too fast

The tension of the first beach party movies comes from love polygons, revenge and redemption schemes, and a whole lot of out-of-touch adults, including a professor literally studying teens in Beach Party. That sort of low-stakes conflict works for a couple of movies, but not much more. Later films introduced more varied villains, who would try to prevent the teens from partying, romancing, or otherwise enjoying their carefree lives. First, it was jocks and land developers in Muscle Beach Party and Bikini Beach. That's fair enough: There are believably conflicting interests that would pit these antagonists against our beach-going heroes. What good is bodybuilding without a tan to match? And what better place to develop a senior retirement home than a pristine waterfront?

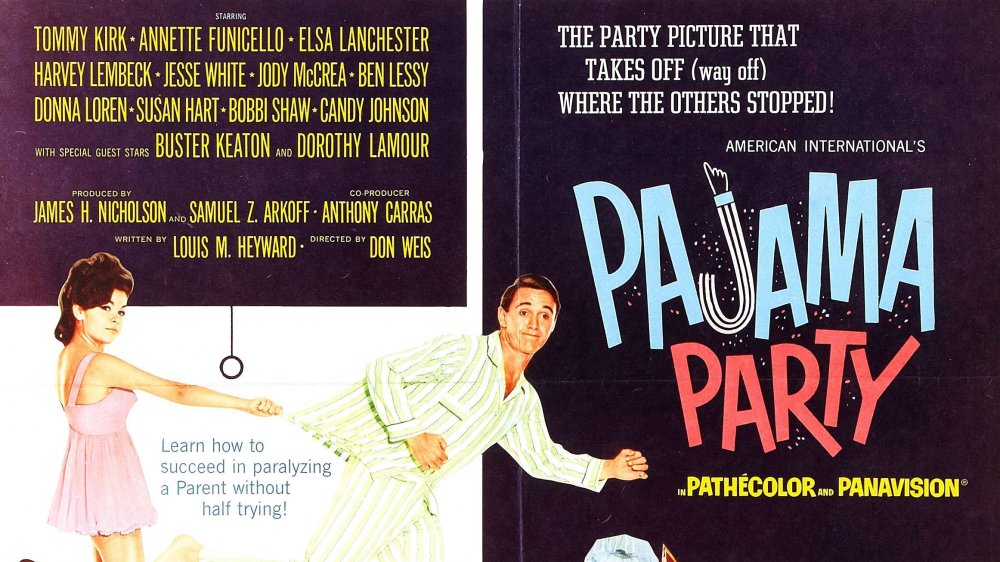

But then, things got weird. Jocks are one thing — martians (Pajama Party) and ghosts (Ghost in the Invisible Bikini) are a little tougher to rationalize. But there just wasn't much else to do with an already immobile genre — variety was needed, and there are only so many believable villains for a squad of sandy teens to oppose. The overcompensation of these larger-than-life-or-death adversaries made that painfully clear.

Simple is hard

Parody is not easy, even when the source material invites satire. Beach Party was a parody, if a light one, of surf movies, which managed to carve out its own niche in the process. It strikes its balance well, but it's an exceptionally difficult one to maintain, let alone imitate. As the genre expanded, this gently satirical nature became cynical. A bizarre sardonicism took hold, resulting in movies that seem to dislike themselves. It's difficult to sympathize with any characterization or plot that occurs, as the tone that surrounds them is nearly mocking.

Later productions attempted to fix this by replacing simple adolescent pursuits with social and storytelling chaos that escalated exponentially. This did not work. Just like a group of oblivious teens, the inventors of the beach party genre were lulled into a false sense of idyllic security by their early success. The simplicity of the formula belied the complexity of its execution. As the quote often attributed to Martin Scorsese goes, "There's no such thing as simple. Simple is hard." Too bad he'll never direct a beach party movie.