15 Foreign Fantasy Movies You Have To See Before You Die

The great thing about fantasy movies is that, as is often true of the shapeshifting characters in them, they can take innumerable forms. And those forms, in turn, can reflect the interests, dreams, anxieties, traditions, and cultural touchstones of any number of peoples and nations.

To prove it, we've compiled a list of 15 underrated yet absolutely brilliant and worthwhile fantasy films hailing from countries other than the United States — from Lebanon, to Martinique, to Australia. Each of these films approaches magic, imagination and the supernatural in its own way, with subgenres ranging from comedy to musical to horror. They're all highly recommended viewing for anyone with a love for cinema about worlds beyond.

Petite Maman

After delivering one of the most acclaimed films of the 21st century with "Portrait of a Lady on Fire," Céline Sciamma decided to adopt a different perspective for her follow-up, zeroing in on the emotional life of a child as an entry point into a broader contemplation of the nature of grief. The result, again, was one of the best female-directed movies of all time.

In 2021's "Petite Maman," Joséphine Sanz stars as Nelly, an 8-year-old whose maternal grandmother (Margo Abascal) has just passed away, leaving Nelly's mother Marion (Nina Meurisse) in disarray. While staying in Marion's childhood home, Nelly goes out to play in the woods and meets a girl (Gabrielle Sanz) her own age who looks exactly like her. The two quickly strike up a friendship, and their subsequent journey puts Nelly face-to-face with the complicated realities of not just her own grief, but also her mother's.

The fantasy element of Nelly's friendship with the mystery girl is best left unspoiled. Suffice to say that, at just 72 minutes, Sciamma makes "Petite Maman" a profound, enormously moving experience, brilliantly employing fairy tale elements to translate life's melancholy mysteries into the emotional language of childhood.

The Enchanted Desna

Between 1954 and 1955, legendary Ukrainian Soviet filmmaker Alexander Dovzhenko published "The Enchanted Desna," a work of semi-autobiographical literature melding childhood memories with fantasy. Following Dovzhenko's death in 1956, his wife Yuliya Solntseva directed several brilliant films from stories written by her late husband, and one of those was a 1964 fantasy drama adapting "The Enchanted Desna" to the big screen.

Solntseva's "The Enchanted Desna" is set in two different time periods, capturing the experiences and reveries of 6-year-old Sashko (Vova Goncharov) along the banks of the Desna river through a series of whimsical, visually stunning vignettes. At the same time, the film shows the adult Alexander Petrovich (Evgeniy Samoylov), now an aging writer and colonel wading through his memories to make sense of his life.

The movie pushes the wistful pastoral splendor of Dovzhenko's own work to even more deliriously beautiful extremes, working out a deeply personal, affection-based theory of Soviet history by masterfully evoking a child's boundless imagination. Unfortunately, "The Enchanted Desna" is nearly impossible to watch in decent quality nowadays, unless you're lucky enough to catch a repertory screening. A restoration of Solntseva's masterpiece is long overdue.

Leila and the Wolves

Lebanese filmmaker Heiny Srour became the first Arab woman to have a film selected for the Cannes Film Festival main competition with her 1974 experimental documentary "The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived," an imaginative and urgent record of the Dhofar rebellion in Oman. Then, in 1984, Srour outdid herself with the docufictional fantasy drama "Leila and the Wolves," one of the most original yet criminally underseen films ever made anywhere in the world.

"Leila and the Wolves" follows Leila (Nabila Zeitouni), a Lebanese photographer in then-modern-day London who visits an exhibit on the history of Lebanese and Palestinian resistance, and becomes distraught at the absence of female subjects in the photos. From there, Leila and the viewer are whisked off into a trip through time, visiting various moments of 20th-century Lebanese and Palestinian women's history through archival footage, re-enactments, and fantasy interludes stitched together by unpredictable editing. It's a kaleidoscope of reality and fiction that Srour conducts with mind-boggling inventiveness and clarity of purpose, overwhelming the viewer with stark, gorgeous images that contain mountains of political significance.

Kummatty

Like other great Malayalam-language filmmakers, the work of Indian avant-garde master G. Aravindan remains criminally underdiscussed in the West. "Kummatty," Aravindan's exuberant 1979 family-friendly fantasy, is a compelling testament to his one-of-a-kind genius.

"Kummatty" is inspired by the eponymous figure from Kerala folklore, a trickster magician who travels around charming children with song and dance. Usually described as a scary villain in cautionary children's tales, Kummatty (Ambalappuzha Ravunni) is depicted more positively by Aravindan's film: Arriving at the village where the film takes place, he is seen with fear and suspicion by the adults, yet his music and magic seem to be bringing unfettered joy to the children's lives and teaching them about their connection to nature. Yet ambivalence remains as to Kummatty's true motives.

Essentially, Aravindan uses Kummatty's impact on the village to experiment with a kind of Kerala-style magical realism, starting from a sober depiction of rural life in his home state before infusing it with mystery and transcendence. To that end, the movie serves up some of the most breathtaking nature cinematography in movie history, complete with an unparalleled use of color.

The Tale of the Fox

There is a common misconception that "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" was the first fully animated feature film in history; not only is this not true, but among the several productions that beat the Disney film to the punch, one was a stunning stop-motion effort completed six years before animation on "Snow White" had even begun.

Directed by the legendary father-daughter duo of Wladyslaw and Irène Starewicz, "The Tale of the Fox" wound up getting caught in post-production soundtracking issues and wasn't released until 1937 — at which point it immediately became a watershed moment in cinema history. Based on Goethe's 1794 telling of the fable of Reynard the Fox, "The Tale of the Fox" centers on Renard (Romain Bouquet in the 1941 French dub), an anthrophomorphic fox with a habit of deceiving other animals to his advantage. One day, tired of Renard's antics, the animals pressure King Noble the Lion (Marcel Raine), to arrest him.

Wladyslaw and Irène tell this fanciful, humor-infused, and surprisingly political tale of community turmoil with such astonishingly expressive animation that the film's 1930 production tag all but strains belief. It still holds up as one of the best-looking animated films of all time, nearly a century later.

Manoel's Destinies

Released as both a film and a miniseries and sometimes known by the title "Manuel on the Island of Wonders," Raúl Ruiz's "Manoel's Destinies" is an extraordinary work of children's fantasy from the mind of one of the most inimitable auteurs of world cinema. Accustomed to making cerebral postmodern masterpieces that turn the rules of cinema and narrative on their head, Ruiz brings his love of bizarre, free-flowing storytelling to the tale of Manoel (Ruben de Freitas), a 7-year-old boy who wanders into a forbidden garden. Among other surreal oddities, Manoel comes across a version of himself at 13 years old (Marco Paulo de Freitas).

Written and shot like a barely-comprehensible yet deeply affecting dream state, "Manoel's Destinies" — in both its film and TV cuts — uses the liminal logic of children's fantasy to plunge into the dormant depths of its protagonist's mind, allowing his bustling imagination to inundate the screen with both beauty and strangeness. It's not a film for everyone, but if you're on its kooky wavelength, you may find yourself reconnecting with feelings and impressions from your own childhood as you watch.

Movie Dementia

In 1986, Brazil was a country in flux. The re-democratization process of 1985 had restored civilians' political participation after a bloody 21-year military dictatorship, yet did little to curtail the power of the country's moneyed elites. Facing a future at once promising and uncertain, maverick Brazilian filmmaker Carlos Reichenbach made "Filme Demência" (since translated to "Movie Dementia" in some English-language databases). Reichenbach's film is a modern adaptation of Goethe's "Faust" set amidst the grimy concrete maze of São Paulo, a mammoth metropolis that encapsulated the contradictions of Brazil's new era.

"Movie Dementia" follows Fausto (Ênio Gonçalves), a wealthy industrialist who becomes rudderless after the cigarette factory he inherited from his father goes bankrupt. When his daydreams about escape to an imagined paradise prove unable to ease the stress of his marital troubles, Fausto picks up a gun and takes to the city streets, where his fate is impacted by Mefisto (Emílio Di Biasi). While taking in the social landscape of re-democratized São Paulo, Reichenbach fuses it with surreal, genre-omnivorous flights of fancy, gorgeously using fantasy to express the dark underside of the dream of economic growth.

The Mad Fox

Japanese movies experienced a profound transformation in the 1960s, veering towards the avant-garde in the hands of visionaries like Kaneto Shindo, Toshio Matsumoto, and Nagisa Oshima. And part of the reason the Japanese New Wave was so momentous was that the "traditional" Japanese cinema being disrupted by it was already, maybe, the most refined and inventive in the world. This is aptly demonstrated by 1962's "The Mad Fox," one of the proverbial last hurrahs of classic-style Japanese filmmaking.

A period fantasy drama from veteran jidaigeki helmer Tomu Uchida, "The Mad Fox" takes place in the Heian period of pre-feudal Japan, and centers on Abe Yasuna (Hashizo Okawa), a court fortuneteller who gets caught up in palatial intrigue. After his lover Sakaki (Michiko Saga) is killed for attempting to conspire in his favor, Yasuna flees the court and winds up finding his way to a band of forest-dwelling shapeshifters. Adapting an 18th-century puppet play, Uchida and legendary screenwriter Yoshikata Yoda put all their powers into crafting a dazzling flurry of theatrical emotions and fairytale colors.

Bird People

One of the most unique and mind-blowing films to have screened at the Cannes Film Festival in the past two decades, Pascale Ferran's "Bird People" is a 2014 bilingual French drama that employs thrilling formal and narrative freedom to better convey the spirit of a quietly incendiary story about personal freedom. For the most part, there are only two characters: Gary Newman (Josh Charles, seen recently in the cast of Netflix's "Away"), an American businessman staying at a hotel next to Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris, and Audrey Camuzet (Anaïs Demoustier), a college student working at the hotel as a maid.

The film's first half, focusing on Gary, is radically mundane, depicting the process by which he carries out the abrupt, seemingly out-of-nowhere decision to set fire to his life, from his marriage to his business dealings. It's in the second, Audrey-focused half that the fantasy elements come in — and the less said about them, the better. Like a rapturous cinematic magic trick, "Bird People" transforms right in front of your eyes into something utterly unpredictable.

Farewell to the Ark

The 1967 novel "One Hundred Years of Solitude" by Colombian literary titan Gabriel García Márquez is a landmark of Latin American magic realism — one of the most significant branches of modern fantasy literature. And, while it's a novel deeply steeped in the specificities of Colombian culture (in fact, its influence was one of the things only adults noticed about Disney's "Encanto"), Shuji Terayama proved in 1984 that the essence of García Márquez's work was universal enough to be ported over to Japan.

The last film completed by Terayama before his death in 1983, "Farewell to the Ark" loosely adapts "One Hundred Years of Solitude," setting its mythical family saga amid the stark beauty of an isolated Okinawan island. The Buendías of García Márquez's imagination become the Tokitos, a family living in a remote village dilapidated by time, impermanence, violence, and the allure of big city life. If Terayama's previous films were defined by their madcap invention and envelope-pushing unwieldiness, "Farewell to the Ark" finds him organizing his surreal cinematic visions into his most mature, ambitious, and symphonic work yet. It's one of film history's great shames that he never got around to building off of it.

Siméon

After directing one of the only '80s movies with perfect Rotten Tomatoes scores in 1983's "Sugar Cane Alley," and then making history as the first Black woman to direct a feature film for a major Hollywood studio with the searing 1989 apartheid drama "A Dry White Season," Martinican trailblazer Euzhan Palcy wanted her follow-up to be something lighter and less thematically draining. And so, in 1992, she released "Siméon," a fantasy-infused musical comedy that turned out to be healing both for Palcy herself and for the lucky few who managed to catch the movie during its very limited theatrical run.

Set between France and Palcy's native Caribbean, "Siméon" stars Jean-Claude Duverger as the titular character, an elderly music teacher who, after his death, re-emerges in the life of mechanic Isidore (Jacob Desvarieux), one of his former students, as a ghostly apparition determined to convince him to parlay his musical talents into a career. In turn, the film, a sunny fable infused with all the joy and color that Palcy had been itching to pour onto the screen for years, parlays Desvarieux's own talents (he was one of the founders of the legendary zouk band Kassav') into positively ecstatic musical sequences.

Celia

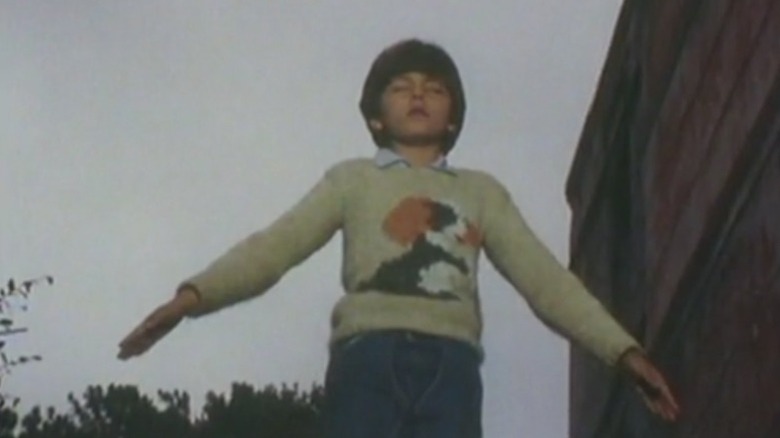

The defining film from underappreciated Australian writer-director Ann Turner, 1989's "Celia" offers up an incomparable blend of genres. It starts out as a social realist working-class drama reminiscent of "Kes" and other British kitchen sink classics. But as Turner presses further on in her exploration of the sociological calamities of rural Australia in the 1950s, it becomes clear that realism is not enough to hold the weight of her themes, and the movie swerves into exuberant fantasy — and concurrently, into horror.

Rebecca Smart gives one of cinema's great child performances as Celia, an 8-year-old girl who, while reeling from the death of her grandmother in 1957, becomes so confused and overwhelmed by the arbitrary mores and hostilities of the adult world that she begins to dream up a fantasy realm to which she can escape. The whole movie is a parable for the feverish insanity of the Red Scare and the insidious presence of hate and bigotry in the lives of everyday Australians, and Turner conducts it with equal parts rigor and terrifying imagination.

A Very Old Story

Although slightly less known in the West than her 1947 take on "Cinderella" (also a great, worthwhile fantasy film in its own right), 1968's "A Very Old Story" (sometimes also known in English as "An Old, Old Tale") is arguably the crowning achievement of Nadezhda Kosheverova, a Russian filmmaker who carved out a niche for herself as one of the Soviet Union's foremost auteurs of children's cinema.

Adapted from several fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen, most prominently "The Tinderbox," "A Very Old Story" begins with a prologue about a wandering puppeteer (Oleg Dal) who asks his puppets to act out a story for him. They proceed to do so, telling of a soldier who is gifted a magical piece of flint by a wizard, and falls in love with a princess who likes to test her suitors with riddles. Kosheverova spins out the story-within-a-story with nimble, granular perfection, evoking an irresistible sense of escapist enchantment with every scene — while also using the film's framing device to comment smartly on the limits of fairy tales as a refuge from reality.

Ruddigore

The films of English animator Joy Batchelor have a buoyancy and an expressive clarity to them that still manage to leave an impression decades later. While Batchelor's best-known movie is her 1954 adaptation of "Animal Farm," connoisseurs of her work often point to a later effort, the 1966 animated opera "Ruddigore," as her true magnum opus.

And there's good reason for that: Adapting a lesser-known Gilbert and Sullivan opera laced (per usual) with dark humor, Batchelor brilliantly matches the sung-through rhythms of opera to animation that feels, itself, endlessly musical. Clocking in at just 54 minutes, Batchelor's "Ruddigore" follows the source material in telling the story of Sir Despard Murgatroyd (Kenneth Sandford), the Baronet of Ruddigore, who has inherited a family curse that forces him to commit a crime every single day, or else die in unimaginable agony. The styles of Batchelor and of Gilbert and Sullivan prove to be perfect fits for one another — with Batchelor's agile, efficient brush perfectly translating the spirit of Victorian England's undisputed kings of absurdist wit.

Grass Labyrinth

Originally produced as one entry in a three-part French package release spotlighting sexually-charged avant-garde films, Shuji Terayama's "Grass Labyrinth" is a more concentrated distillation of the bonkers brilliance he later applied to "Farewell to the Ark." For those who already consider themselves fans of Terayama's irrepressibly original style, it should prove a delectable treat — and, for everyone else, it's guaranteed to be a cinematic experience like no other.

Liberating himself almost entirely from narrative formality, yet retaining a stringent preoccupation with the tenets of framing and composition, Terayama follows Akira (Takeshi Wakamatsu), a young man on the cusp of adulthood, as he journeys into his own subconscious. Akira is fixated on remembering the words to a song that his mother (Keiko Niitaka) used to sing to him as a child (Hiroshi Mikami). That self-searching mission pulls him deep into a surreal web made up of his own memories and dreams. Soon enough, Terayama is using the anything-goes freedom afforded by the premise to splash the screen with his wildest visions and ideas. The result is a fantasy film that goes all the way to the farthest reaches of what fantasy can be.