'70s Horror Movies That Were Way Ahead Of Their Time

There have always been movies ahead of their time. Sometimes, a fantastic film comes along that, even if it isn't reviewed favorably at first, receives a critical reassessment, with people realizing that the project was actually on the forefront of something truly remarkable. Maybe it becomes a cult classic after its release, steadily gaining an audience that puts it back on the map as people realize how well it handled certain themes. Or perhaps it receives a new edition that brings it back into the spotlight, prompting people to reconsider it.

The horror genre has always had movies ahead of their time. It's how the genre continues to evolve, from the era of slashers to the numerous found-footage options that hit the scene after "The Blair Witch Project." Whether they're identified upon release or decades later, these are the horror flicks from the 1970s that stand as films ahead of their time, from the themes they explore to how they handle their main characters to even their editing style.

Alien (1979)

"Alien" is a phenomenal movie for many reasons. It's widely considered one of the most influential films in the genres of horror and science fiction, with the bleakness of the plot continuing to resonate with audiences decades later. Roger Ebert wrote in 2003 that one of the most notable strengths of "Alien" was its pacing, highlighting how it lets silence speak, with a slow and steady build-up to the horrors that await the crew.

But what really made "Alien" ahead of its time was Sigourney Weaver's performance as Ellen Ripley. Not only is the movie an important building block in her career, arguably putting her on the map, but the feminist undertones of Ripley's story help audiences connect with her. She's a strong female character who acts in a leadership role and survives against the odds thanks to her own intellect. While we see this often in more modern horror with projects like 2014's "A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night," "Alien" explores it in a way that redefined the genre and made Ripley one of the original final girls.

Weaver agrees with this assessment. "They thought that the audience would never suspect that the young woman was going to be the hero, essentially the survivor," the actress said to The Hollywood Reporter in 2025. "It's amazing to me how influential the character of Ripley has been. I think it's because she reminds us all that we can rely on ourselves, and we don't need a man to fly in and save us or something like that."

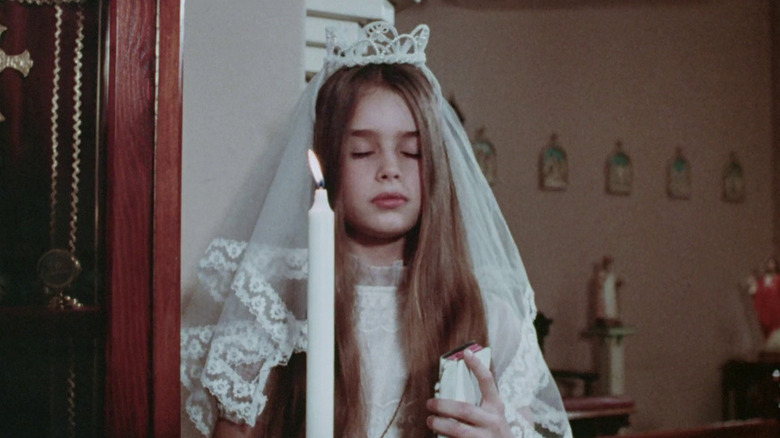

Alice, Sweet Alice (1976)

"Alice, Sweet Alice" may appear like a standard creepy kid flick, with one sister accused of murdering another, but the movie is so much more than that. The plot shifts back and forth, leaving audiences to question whether the titular Alice (Paula Sheppard) is responsible for her sister Karen's (Brooke Shields) death as the film reveals the former's true nature. She's violent with others around her, including animals, and even threatens her sister at the beginning, immediately setting the tone for what to expect.

Told against the backdrop of Alice's sister dying seconds before her First Communion, religion becomes an important theme, and is why "Alice, Sweet Alice" has become a point of interest for film theorists. The movie sparks discussion about how people internalize religious teachings, particularly in Catholicism, and the guilt that comes with disobeying them. Alice's now-divorced parents had her out of wedlock, and one way to interpret the narrative is that God is punishing them through the death of their second child.

Additionally, the nuclear family is falling apart, with the parents' divorce and a daughter's death. When that's juxtaposed against the Catholic church setting, it forces you to question the traditional teachings of the church, how that's impacting the family, and if the burning of Karen's body is meant to function as a way to "cleanse" the family of their sins. These undertones make "Alice, Sweet Alice" ripe for discussion about the depictions of religion and religious thought at the time, a topic rarely explored in the genre previously.

Don't Look Now (1973)

"Don't Look Now" follows a married couple trying to move forward in life after the death of their daughter. They head to Venice, where husband John (Donald Sutherland) is set to help restore an old church. However, he starts seeing strange things, confused about what's actually happening around him.

The movie is an exploration of how different people work through grief, both separately and together. As a couple, they are forced to confront how it will impact their life together, but they must also figure out their own feelings about it. It's a hard truth that many don't want to face because, at the end of it all, their marriage may not survive. While relationships were certainly featured in horror films previously, "Don't Look Now" was ahead of its time in how it highlights grief in relationships, particularly when combined with the unconventional editing.

The film's innovative editing style forces the audience to question what they're seeing, a technique that aligns more with contemporary movies than with those released in the 1970s. It makes the horror of it all that much more impactful as you realize nothing is what it seems, setting "Don't Look Now" apart from its peers.

Long Weekend (1978)

"Long Weekend" takes audiences on a camping trip with a couple, Marcia (Briony Behets) and Peter (John Hargreaves). They're pretty destructive as they go, causing fires, chopping at trees for sport, and killing quite a few animals. The environmental harm doesn't go unnoticed as nature begins to take its revenge.

Though not the first movie of the decade to address the topic, "Long Weekend" does it the best among its peers. It not only features nature going to great lengths to ensure Marcia and Peter don't survive the weekend, but it also hints at what will come of the couple from the start of the film, specifically when a news report discusses weird bird attacks. It all feels like how a director might approach a project commenting on climate change today, with the planet causing unusual animal behavior or trying to make an example of someone.

"Long Weekend" also sets up a conflict that is still topical: Marcia and Peter fighting about abortion. Marcia had an abortion after having an affair, and it's clear that the affair and accompanying abortion are a sore subject for the couple. When this revelation comes, it helps make sense of the tension of the trip and why both are seemingly acting out. Even today, abortion isn't a topic that comes up often in film, so seeing it featured in horror from the 1970s makes "Long Weekend" ahead of its time.

The Brood (1979)

When you think of horror director David Cronenberg's resume, the films that probably come to mind first are "The Fly," "Shivers," or maybe even "Videodrome." They're all amazing movies, but one that doesn't always get enough attention is "The Brood."

"The Brood" is ahead of its time because of how it frames the narrative of a married couple fighting for custody of their daughter, Candice (Cindy Hinds). Cronenberg wrote the movie after going through a divorce, and that comes through in how the film focuses not only on the crumbling relationship, but the lengths each parent is willing to go through to "win" what they want, while including the relatable fear of being a "good" parent. The wife, Nola (Samantha Eggar), sees a psychotherapist to work through her past and how it's impacting her mental health in the present, which in turn is something her husband, Frank (Art Hindle), is attempting to use against her in the custody battle.

While the story tumbles into something bizarre, the underlying themes surrounding parenting, mental health, and maternal power stand out, earning "The Brood" a place in film theory discussions. In particular, theorists argue that the movie shows the real issues with misogyny in media: how men portray women. "The Brood" artfully depicts two different men, Nola's husband and her psychotherapist, who ultimately attempt to mold her into what they want her to be.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.