How They Really Pulled Off These Classic Hollywood Special Effects

We're used to incredible effects in our movies these days. Not only do we believe a man can fly, we believe he can shoot lasers out of his hands, summon lightning from the sky, shrink down to the size of an ant, and blast high-powered photon charges at any approaching enemy — and that's just the Avengers. We watch Pennywise's face break apart like an old clay pot, Daenerys Targaryen decimate an army atop her jet-sized dragon, and Rick Grimes face down an army of the rotting, stumbling dead, and we don't set back in sheer awe, wondering how such a feat of visual splendor was accomplished. We know already: computers. Most of us don't know much in the way of detail beyond that, but we don't need to. At this point in cinematic history, given enough money, manpower, and technological access, we can regularly and reliably make the impossible into the everyday.

But there's something special about old-fashioned special effects. Modern high schoolers still take theater tech classes to learn how to make fake wounds and battle scars. Star Wars is lauded for continuing to employ practical effects. And we return, year after year, to watch the wonders accomplished on screen before CGI was omnipresent. It was arduous work that took hours, often went wrong, and gobbled up money by the walletful, but it resulted in incredible art. Join us as we look back on the high points of special effects in classic Hollywood, and appreciate their feats anew.

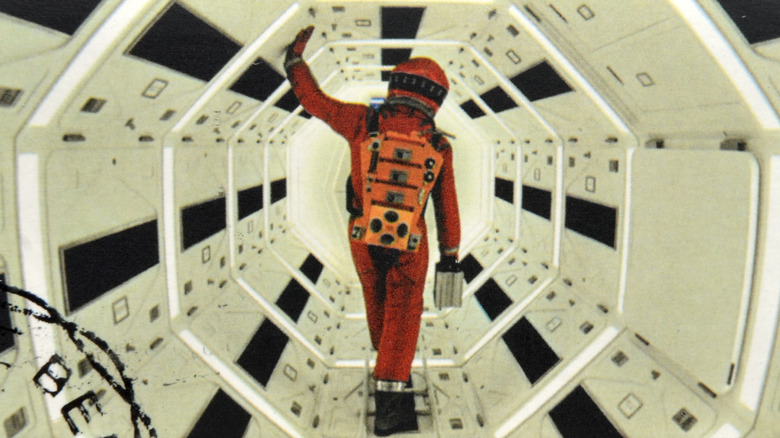

The star gate from 2001: A Space Odyssey

2001: A Space Odyssey remains unlike anything else, even decades after its debut. A dizzying blend of sci-fi fantasia and existentialism, it still inspires debate and discussion among any given group of nerds as readily as the latest Marvel movie. From the mysterious nature of the Monolith to the meaning of the "Star Child" seen looming beside the Earth at the end of the film, 2001 resists all attempts to categorize it as any one genre, assign one set meaning, or predict whatever one cares to argue that it predicted.

One thing's for certain, however: just how trailblazing and spectacular 2001's special effects are. One of the most famous is the "star gate" sequence, a kaleidoscopic journey through time and space visualized as a pulsating whirl of color. Slit-scan photography was used to accomplish this, a process in which a slide with a slit cut into it is inserted between the camera and the object being filmed. Everything from dripping paint to shots of the Hebridean islands were filmed and used. What it all adds up to is a sequence as trippy as it is alienating. It looks like nothing else, because its creation was a one-of-a-kind effort.

The chestburster from Alien

Alien is the kind of movie everyone has a favorite moment from. But regardless of whether you're someone who lives for the climax in which the alien gets blown into space or you just love Ripley's cat, chances are you remember the infamous chestburster scene. Even today, when the world is absolutely bursting with movies full of splattery gore (now with pixel-perfect polish), there's still something about seeing that larval horror erupt from a human body. It's gross, it's shocking, and even those who've seen it before brace for its impact every time the scene approaches.

So how did they make it happen? An artificial torso was created, filled with blood and viscera, and manipulated by a puppeteer who operated the monster itself. Actor John Hurt's head and arms were visible above and on either side of the fake torso, which rested upon a table with strategic holes cut into it. Infamously, though the cast knew some details of the scene, they did not know the torso would be spraying blood via hydraulic pumps, and as a result, much of the shock captured on their faces is entirely real. That's right: for once, the actors on screen are just as horrified as the audience. It's no surprise that the scene is considered one of the most memorable in film history.

The naval battle from Ben-Hur

An entire generation now removes us from Ben-Hur, the landmark drama starring Charlton Heston as a young Hebrew prince living in the age of Jesus and his miracles, and yet we still live in its grand and glorious shadow. From the sweeping score to the sheer scope of the manpower involved in making the movie — thousands of men, camels, and horses came together to make this juggernaut happen — it has influenced decades of filmmaking on every possible level. Who could forget the nine-minute chariot scene or the lavish excess of Quintus Arrius' villa? Learning about how Ben-Hur was made, in fact, only magnifies the magic of the movie. It really did take a once-in-a-lifetime sort of miracle to make a story like this a reality.

The naval battle scene stands out as a particularly impressive bit of stagecraft, even today. To make it happen, more than 40 miniaturized Roman trireme ships were created and floated in an enormous tank on the MGM Studios backlot. Two separate and entirely seaworthy vessels were created for the scenes taking place above-deck and within the ship, built according to plans for actual Roman galleys. To accommodate these ships, an artificial lake, equipped with the machinery to produce waves, was built at Cinecittà Studios in Rome, along with an enormous painted backdrop capable of hiding the real-world surroundings. Many of the miniature boats survive to this day, and remain marvels of set design and engineering.

"HELP ME" from The Exorcist

The Exorcist is full of unforgettable images. There's just something about the contrast between Regan, a young girl in an old-fashioned nightgown, and the more and more deeply depraved acts she engages in, from spider-walking down the stairs to some truly shocking acts of blasphemy. Something terrible and beyond human reason has entered the lovely American home the bulk of the film's action takes place in, and it is terrifying to watch it subvert the normal order.

One of the scariest moments is, in fact, one of the simplest: when the words "HELP ME" appear on the possessed Regan's stomach, as though scrawled from the inside. It's a desperate scream for help, written in the most primal way. Regan is alive, buried in her own body, carving words into her very flesh in the hope of salvation. Of all the effects produced for this movie, it's one of the most convincing — and the most disturbing. The filmmakers created the letters by painting the words onto a foam latex stand-in stomach with cleaning fluid, then heating them with a hair dryer to make them deflate. When played backwards, footage of the process made it look as though the letters were rising, unbidden, to the surface of Regan's belly. A simple process, yet a devastatingly effective one.

The mothership from Close Encounters of the Third Kind

There's nothing that dazzles filmgoers quite like outer space. You can play up the psychedelia, as with 2001: A Space Odyssey. You can emphasize the isolation, as with Gravity. And there is, of course, always a big ol' spaceship. Steven Spielberg chose this route when he revealed the alien mothership at the end of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, a luminescent wonder of machinery and lights. The ship is fringed with points and spires, the top of it appearing almost to be a cityscape unto itself. Its level of detail is extreme, even when compared to the sci-fi spectacles of the time (Star Wars, of course, being the most notable) — every strut and buttress is a minute wonder.

Just how did they pull off something so grand? It's simple: they built it. The mothership is a fiberglass model, currently on display in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum's Udvar-Hazy Center, and it's no less spectacular in person. Built by a team headed by the masterful Gregory Jein, parts of the ship were, in fact, borrowed from hobbyist model kits. Multicolored lights installed beneath the model give it a friendly yet still deeply strange air, and strategic camera shots made it appear enormous and supernaturally hued. Though the hidden R2-D2 on its surface has become infamous, the sharp-eyed seeker can also find a mailbox, a Volkswagen bus, and even a tiny cemetery within its many parts.

The twins in The Parent Trap

The Parent Trap still manages to astound modern audiences with its clever doubling of star Hayley Mills. Even those raised on the 1998 Lindsay Lohan reboot can't quite shake the magical feeling of watching two of the same person in one shot, from an era when computers still took up entire rooms and we were going to space on the computing power of the smartphone in your pocket. There are no shuddery shots or obvious seams, no moment you can point to as the movie showing its age. Almost thirty years passed between the original and the reboot and despite cosmetic and era-appropriate changes, they really didn't have to improve upon the technology of the original incarnation.

How did they do it? Originally, there were only a few moments of trick photography called for. When the sodium vapor process — a method of photochemical processing used extensively by the Walt Disney Studios — was employed, however, the filmmakers were so delighted by the effect that the script was revisited. Notably, the process produces much cleaner results than that of the then-common use of blue screens and contemporary audiences were dazzled by the effects. The process would go on to be used in everything from Mary Poppins to Bedknobs and Broomsticks, and was only retired when computers ushered in a hitherto undreamt-of level of sophistication. But the results don't lie: The Parent Trap still looks great.

The Gunslinger's viewpoint from Westworld

HBO's reboot of classic science fiction thriller Westworld has audiences captivated. Cowboys! Robots! Cowboy robots! Evan Rachel Wood, Thandie Newton, Ed Harris, and other such luminaries explore the darkest corners of artificial intelligence against a strikingly varied set of landscapes, and fans are hooked. Money and expertise clearly aren't being squandered as the show traipses through feudal Japan, sanitized surgery theaters, the dustiest plains of the West, and luxurious housing for the Westworld technicians. It never looks slapdash, unconvincing, or indeed, anything less than beautiful.

But you know what? You can say that about the original Westworld too. The 1973 thriller starring Yul Brynner doesn't just hold up today as a great movie but as an early pioneer of computer graphics in film. Westworld was the first film to use digital image processing to portray the world through Brynner's Gunslinger android's eyes: heavily pixelated, blockily colored, and totally alien. Footage was separated into three primary colors and then painstakingly pieced back together into a coherent sequence the audience could recognize.Though the sequence takes up less than three minutes of the film's runtime, it was totally unprecedented and still manages to impress. The Gunslinger isn't human, and his viewpoint proves just how scary that is.

The bird attacks in The Birds

Alfred Hitchcock made an everyday animal into a terrifying force of nature in this 1963 horror classic. Who can forget the look in Tippi Hedren's eyes as she cowers in a bird-besieged phone booth? Who can't immediately conjure up the final shots of the thousands of birds perching ominously over town? Birds can be symbols of peace, good fortune, and love, and are often even doted-on pets kept in family homes. But Hitchcock managed to sweep aside those associations in favor of another: birds as carrion creatures with an eternal height advantage, acting according to inscrutable avian desires.

So how did they do it? Well, quite a few of them are actual birds. Some are wild (many of the seagulls were actually rounded up from a garbage dump) and some were borrowed from pet shops. Then came the complicated process of piecing the scenes together. As in The Parent Trap, the sodium vapor process was used to compile shots of the birds attacking. Most impressive was the creation of the scene in which sparrows attack through the chimney. Legendary Disney animator Ub Iwerks took footage of sparrows flying in an enclosed glass booth and superimposed it upon shots of the home's interior, allowing him to multiply them in number and capture their movements with precision. All in all, it adds up to a terrifying movie that forever changed the way a generation would look at crows resting on telephone wires.

The Red Sea parting in The Ten Commandments

How does one even begin to discuss The Ten Commandments? It adapts one of the most famous and influential stories in all of human history. At the time of its release, it was the most expensive film ever made, and remains one of the most successful of all time. It's a once-in-a-lifetime collaboration between the greatest stars and creators of an era working together to bring a legend to life. It's a testament to everything that made the Golden Age of Hollywood so culture-changing. It is, simply, an epic.

No scene embodies that spirit more than that of the Red Sea parting. Making it happen was no mean feat, even in a film that also brought to the life the Angel of Death and Moses' pillar of fire. Rear projection was used to place Charlton Heston's Moses against a stormy background of clouds and fog — a simple technique, but performed and framed so expertly as to be powerful enough on its own.

To create the moment of parting, shots from the actual Red Sea were combined with shots of water manipulated on the Paramount backlot. Artificial waterfalls were created using troughs and hundreds of thousands of gallons of water to simulate both the parting of the sea and its crashing back together. These techniques, combined with the then-new widescreen VistaVision film format, came together to bring one of the most thrilling stories of all time to an unforgettable climax.

The transformation from An American Werewolf in London

Ah, to be a young person abroad. Everything from Eurotrip to Roman Holiday has used this rite of passage as a jumping-off point for great storytelling, but most keep it light, breezy, and focused on freedom. Enter An American Werewolf in London, which combines the trill of adventure and the horror of hungering for human flesh.

Many elements of the film are impressive, but nothing quite compares to the scene in which protagonist David, once an innocent backpacker and now a cursed abomination, transforms into a werewolf. Suddenly burning hot, he rips off his clothes and watches in horror as his hands and ankles lengthen, hair sprouts across his naked skin, and his skull contorts into a lupine snout. Makeup mastermind Rick Baker and 30 technicians are to thank for this painstaking metamorphosis. The team used prosthetics, rubber masks, and makeup that required ten hours to apply and three to take off to create the tremendous effect.

Manipulatable body casts were used to make it look as though bones were lengthening, especially during a shot in which David appears to be on his back, seen in his entirety, struggling against his body's rebellion. Actor David Naughton was, in fact, hiding in a hole cut in the set's floor — the "body" we see is a cast. It's no surprise that this film netted Baker an Academy Award and an eternal place in film history.

The trench run from Star Wars

Picking a favorite Star Wars scene is like picking a favorite day of the year. There are just so many that are full of humor, heart, and cinematic razzle dazzle — how could you possibly narrow it down to one singular expression of its classic appeal? Some prefer Han Solo's cocky charm. Some are all about Darth Vader's brand of signature menace. And some — many, really — just love the action. We're all that last group, really. Who could forget the climactic lightsaber battles, the daring ballet of rebel pilots flying through space, or our heroes acrobatically flipping away from the Sarlacc pit?

There's one moment that stands out in particular: the "trench run," wherein Luke Skywalker narrowly avoids Darth Vader to make it to the exhaust port and blow up the Death Star. This was accomplished through some truly impressive effects work and engineering. Visual Effects Supervisor John Dykstra developed a computer-controlled camera system, dubbed the "Dykstraflex," to make the high-speed motion of the interstellar dogfights feel thrilling and immediate. This system, used in concert with the miniature models produced by Industrial Light and Magic's legendary model shop, plus shots of explosions blown up and inserted into the scene, created the edge-of-your-seat tension that makes the scene so memorable.