That's What's Up: Whatever Happened To Superhero Comics In Newspapers?

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: Whatever happened to comic strips of superheroes? Once they were more legitimate than comics, but now they seem forgotten, even by experts. — @Ettore_Costa

I don't know what so-called experts you've been talking to, my friend, but I have some good news for you: I'm not sure there's any piece of obscure comics history that I've ever forgotten about. I mean, I'm a dude who remembers the four-issue series from 1992 about the Power Team, a group of real-life Christian weightlifters who used to perform feats of strength inspired by Jesus at school assemblies in the South. If I know about that, I'm pretty sure I can rustle up a few ideas about superheroes and their attempts at cross-media success.

Not that this topic is pretty obscure. In 2019, the superhero influence on newspaper comics might be limited to a surprisingly ineffective version of Spider-Man being bonked on the head a bunch, but actually getting to that point is a little more complicated. It's a journey that goes through the creation of mass media, the Senate hearings that led to the Comics Code, and even the dawn of the internet, all explaining how superhero comics went from being the Next Big Thing to a second-class hobbyist's media, and all the way back around to being the source material for the most prominent piece of media of the past decade. And believe it or not, it actually starts almost a decade before Superman made his first appearance.

A (mercifully) brief history of sequential art

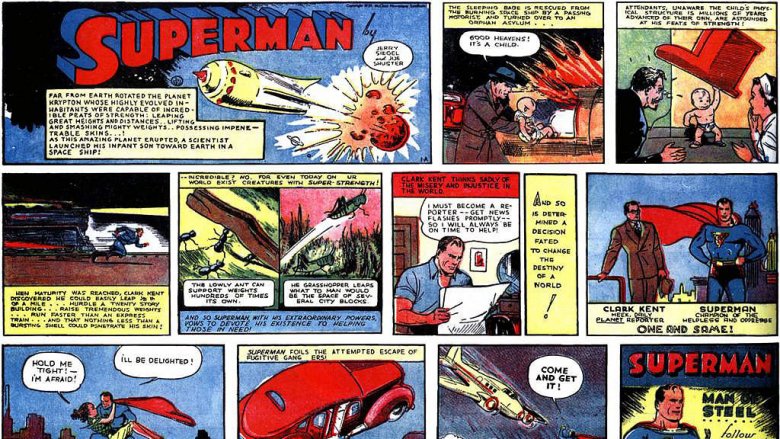

So, first things first: we can all probably agree the superhero genre started in earnest in 1938, when Action Comics #1 introduced the world to Clark Kent and his bullet-racing, locomotive-stopping, building-leaping alter-ego. There were plenty of influences that laid the groundwork, of course — Batman in particular has a heritage that winds its way back through Zorro, Sherlock Holmes, the Baroness Orczy and her famous Scarlet Pimpernel, and, most directly, the Shadow — but at best, those were the ingredients. Superman, on the other hand, was the cake, a herald of a new genre that would spawn countless imitators over the next few years.

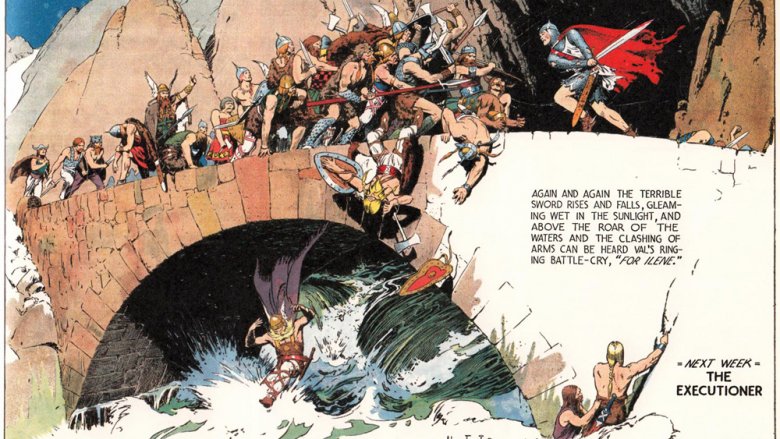

Comics as a whole, however, have a much longer history, and not just in the Scott McCloud "cave paintings were sequential art" sort of way. It would certainly be refined over the years, mostly in the pages of superhero stories for reasons that I'll come back to in a second, but the visual language that we all recognize as "Comics" started in newspapers. There's a direct throughline from the popular newspaper strips of the '30s, like Alex Raymond's Flash Gordon and Hal Foster's Prince Valiant, which debuted in 1934 and 1937, respectively. Those were massively influential, and it's easy to see why — not only were they widely distributed, they were beautiful, even by today's standards. Of course, if you told most of today's comics artists that they could get by with only producing a single page every week and have it read by millions, they'd probably drop some pretty high quality work, too.

Point being, comic strips were the foundation of these ongoing adventure stories that were never really meant to end. If you really want to see the best example of how that translates into mass media success, though, you can skip Foster and Raymond and go back a little further to what might be the most important pre-Superman comic of all time: Mickey Mouse. Yes, really.

The epic adventures of Mickey Mouse

Mickey Mouse wasn't the first great adventure strip — Winsor McCay's Little Nemo in Slumberland started all the way back in 1905, although that's a different sort of adventure than Mickey's action-packed hijinx — but it's easy to argue that it's the most important. That's partly because its star would quickly become the flagship character of a massive corporate entertainment empire, but it's just as important that it was among the most well-crafted comics I've ever read.

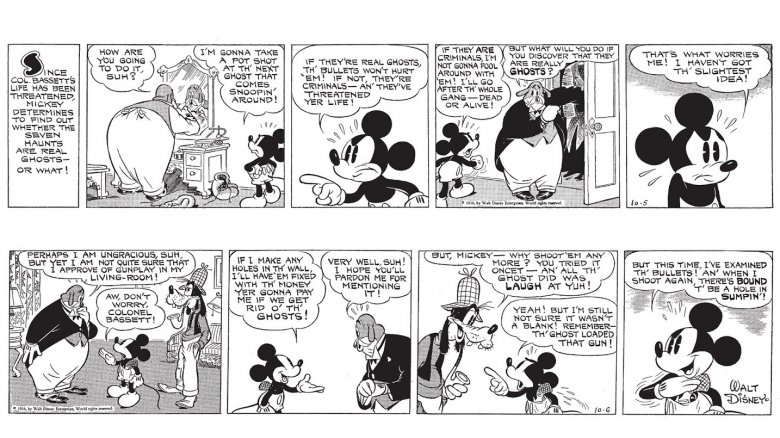

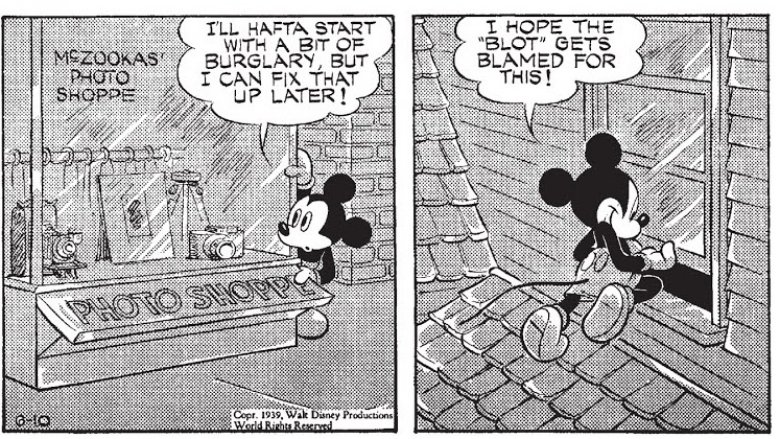

The strip was originally produced by Mickey's creators, Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks, but four months into the run, they handed it off to Floyd Gottfredson, who might be the greatest cartoonist you probably haven't heard of. Under Gottfredson, Mickey was virtually unrecognizable to those of us who are used to the more modern, achingly family-friendly version. There were plenty of strips that built to simple gags in the last panel, but more often than not, Gottfredson's Mickey was a two-fisted, wise-cracking, pistol-packing underdog adventure hero who bounced from genre to genre and odd job to odd job, from whaling to flying a mail plane to joining the Foreign Legion to occasionally taking freelance detective work from the chief of police. It's the latter that led him to cross paths with the Phantom Blot, a Gottfredson creation that would go on to become the closest thing Mickey has to an arch-enemy besides Peg-Leg Pete, but that was far from his only great adventure.

Before you run out and grab them, though, I do need to say that unfortunately, I can't give it an entirely unqualified recommendation. I don't want to excuse it as a "product of its time," but like a lot of media from the '30s, Gottfredson's work occasionally includes extremely regressive and offensive racial stereotypes, sometimes even as the basis for an entire story arc. It's even worse than those elements usually are, because aside from that one flaw, the first decade of Mickey Mouse is a nearly perfect adventure strip from a craft perspective. Even if it's the only one, though, it's a hell of a flaw to get past.

Black and white and read all over

Here's why all of this is so important. Mickey had no shortage of appearances on the movie screen — after his 1929 debut, he'd starred in 50 shorts by the end of 1932. Still, seeing those still required potential fans to pay for a ticket to the movies, something that was getting pretty difficult as the Great Depression wore on, and once they were over, all you had was the memory unless you wanted to pay to see them again. Newspapers, on the other hand, were a true mass medium with an established (and massive) distribution among the public. There was a cost for entry, of course, but for all their popularity with readers, comics were almost a bonus feature added to the primary purpose of, you know, news. If you're already paying a dime to find out, say, what's happening in Europe in the '30s, which was kind of a big deal, then the comics that you get along with it are an afterthought.

That meant that people (particularly families, and even more particularly, kids) who were already getting the newspaper were seeing Mickey in a new strip every day and following him through adventures that were at least as good as his cinematic stories. That's accessibility, which leads to familiarity, which leads to affection, eventual nostalgia, and everything else that makes people fans. It's as true today as it was in 1934: if you like reading about someone in comics, then you're also going to see them in a movie.

If I had to guess, I'd say that Mickey's overwhelming popularity in the '30s was as much a product of the comic strip and the familiarity that comes with seeing something every single day — especially if it's as well done as Gottfredson's work usually was — as it had to do with the movies. It's just what happens when you break into mass media. The "mass" is there for a reason.

This IS the news!

So! Cut to 1938: after years of unsuccessfully pitching different versions of their creation, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster finally get National Comics to publish a new character called Superman. Within two years, there's a massive explosion of knockoffs and new characters wedging their way into this new genre of "super-heroes," including a thinly veiled take on a popular pulp character, Batman. Superman himself is appearing in two monthly mags, as the headliner in Action Comics as well as the star of one dedicated entirely to his adventures. He has become an overwhelmingly popular character, but we don't know that because of the comics — or at least, we don't know that just because of the comics.

We know it because Superman was also succeeding in mass media.

In Superman's case, the big thing was the radio show, a daily broadcast brought to you by Kellogg's Pep Cereal! It was a massive hit, but more than that, it was accessible to anyone who had a radio, which in 1940 was as ubiquitous as televisions are today. It was so popular, in fact, that the comics started taking cues from the radio rather than the other way around, lifting elements like Kryptonite (originally introduced so that voice actor Bud Collyer could take a day off while his character was incapacitated) and Jimmy Olsen (brought in so Superman would have someone to explain things to in a purely audio medium) and incorporating them into the comics. And naturally, there was also a newspaper strip, providing even more daily adventures of Superman.

Crunching numbers

And now, the reason that all of this actually matters. At its height, in the 50s, Superman comic books were selling around a million copies per issue. Comics back then were often passed around entire neighborhoods, so if you're looking for an actual number on readership, we can probably multiply that by three or four, maybe even five. That's a lot of readers, and anyone who had 5,000,000 people reading their stories at any point in comics history would be downright ecstatic.

At its height, The Adventures of Superman comic strip ran in 300 newspapers, giving it a total circulation of twenty million. If half of the people who bought those newspapers read the strips, that's twice as much as our best-case estimate of how many readers the comic had. If you want to know why pop culture as a whole remembered Superman so well while Captain Marvel — a.k.a. Shazam, who was outselling Superman by at least a couple hundred thousand in the '40s — never had the same kind of impact, that's why. Captain Marvel never made it to newspapers.

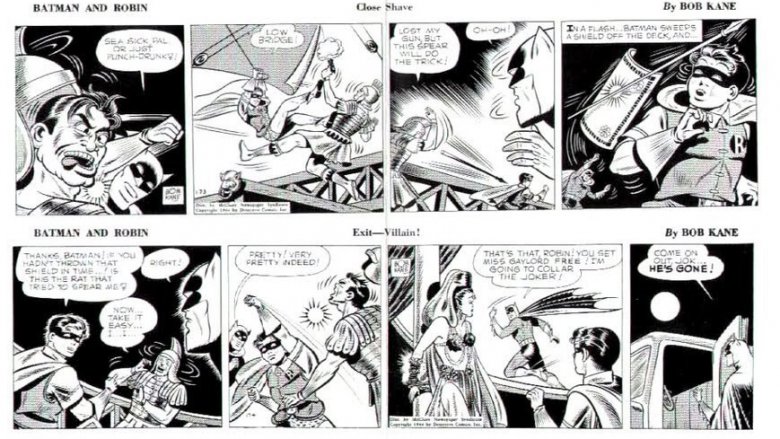

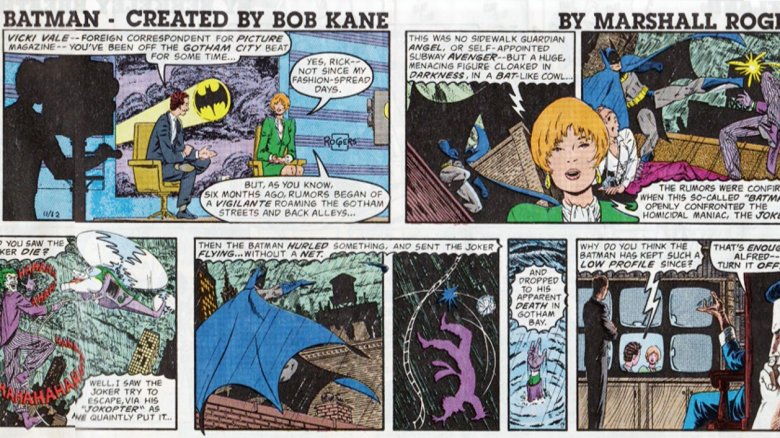

Along the same lines, there was a Batman strip, too, launched in 1943. In fact, I've heard some people theorize that those were some of the few Batman stories that co-creator Bob Kane actually drew rather than having people ghost for him, because it was a much more prestigious job than the comic books were. Jerry Robinson, who was actually drawing a lot of the comic books at the time, said as much, referring to the strip as "glamorous" compared to the books, even if he preferred the latter. As for me, I have my doubts that Kane did much of the work on them for long, mainly because they're, you know, good.

So what happened?

Which brings us back to your initial question: if the newspaper strips were such a big deal back in the early days, what happened? Well, it's the same thing that happened to everything else: Frederic Wertham and Seduction of the Innocent.

If you're not familiar, the short version of the story is that Wertham was a psychologist who was deeply concerned about the negative effects that comics had on The Youth, with crime and horror titles breeding violent psychopaths and superheroes like Batman promoting, and I quote, "a wish dream of two homosexuals living together." The result of this obsession was a book called Seduction of the Innocent, which despite being poorly researched and constructed was influential enough to get Congress to start having hearings about comics. The eventual result was the Comics Code and a set of regulations that basically put DC and Archie's primary competitors out of business, but also gave comics as a medium a bad reputation, with an unexpected side effect.

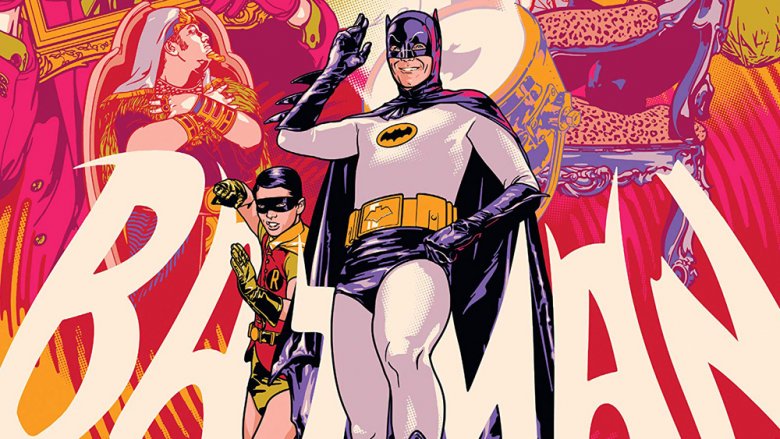

In the mind of the public, comics were forever linked to the idea of being "low art" for children, and superheroes, as the genre that was both specifically created through that medium and was the last genre standing after the Comics Code gave everything else the axe, were too. You can see it in the way the mass media that was based on comics over the next few decades treated their source material. The 1966 Batman TV show was based entirely on the premise that presenting this nonsense like it was Serious and Important was inherently hilarious, and the 1978 Superman movie went out of its way to present itself as being actually Serious and Important, to the point of that weird opening scene with the fake cover of Action Comics #1. I will never understand why they didn't just use the real one, especially since it's one of the most well-known covers of all time.

Ill-fated revivals

Speaking of mass media, there actually were a few attempts to revive superheroes in newspapers, but they were always tied in with a push that came from outside of comics. There was another run of Batman strips launched in 1966 to go along with the TV show; The World's Greatest Superheroes, which prominently featured Superman, began to run in '78; and a third run of Batman launched in 1989 to go along with the Tim Burton movie. None of these were abject failures or anything — the shortest one was the '89 Batman strip, which was drawn by Marshall Rogers and ended in 1991 — but they didn't stick around that long, either.

The one exception? The Amazing Spider-Man, which debuted in 1977 and is still running today. As for why that is, I have no idea other than the simple fact that people really like Spider-Man, as evidenced by the past few years of pop culture.

What's weird about the Spidey strip, though, is that it has become a weird tie-in to other pieces of Marvel's non-comics media. Almost every time there's a Marvel movie in the theaters — so, you know, all the time for the past ten years — its primary characters will show up in the newspaper for a truly bizarre guest appearance. The one running right this second features Luke Cage, but my all-time favorite is when Wolverine and Sabretooth showed up and just punched each other into mutual unconsciousness while Spider-Man watched from the sidelines.

The decline and fall of a media empire

What's really weird about all of this is that here in the present, the roles of those different media have completely flipped. Superheroes are now at the center of the most popular (and profitable) mass media of our time, but now that they're big enough to reclaim that pop culture prominence, they've gone well beyond needing newspapers to prop them up. As vital and important as they are, newspapers have lost a lot of their status thanks to competition from other forms of mass media, like 24-hour TV news and the immediacy and accessibility of the Internet. At this point, I feel like introducing a high-profile superhero comic strip that would only run in newspapers would actually feel like a step down compared to, you know, movies that are raking in billions-with-a-B and sprawling interconnected universes on television.

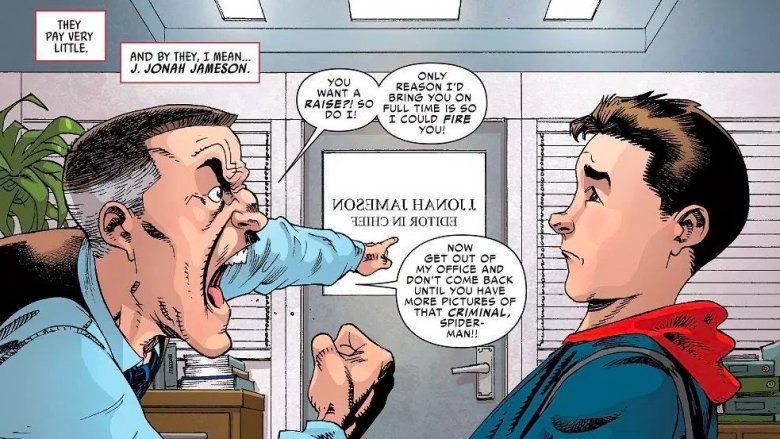

Maybe that's why J. Jonah Jameson is so angry all the time. I mean, it would certainly explain why Newspaper Spidey spends so much time getting bonked in the head with pipes, something that certainly feels like an edict from a vengeful editor. Either way, it seems like the age of superheroes finding a foothold in the newspaper is over.

Which, honestly, is probably a blessing for them. Nobody wants to compete with how good Nancy is these days.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."