Get Ready To Compete With These American Gladiators Facts

It's hard to fully encapsulate the early '90s cultural phenomenon that was "American Gladiators," but any fitting tribute would include some mention of blood, sweat, peroxide, and spandex. Long before networks like Bravo and TLC would morph into reality TV, the genesis of the unscripted television era would emerge in vibrant red, white, and blue. Slowly but steadily, viewers across America began tuning in to behold real-life action heroes telling their powerful stories and facing off for the ultimate glory. We laughed, we cried, and we rooted for them as they dislocated each other's shoulders.

Campy and heartfelt, powerful and raw, the oiled-up glam of "American Gladiators" has become a time capsule of the era, capturing the zeitgeist of the years between Reaganomics and grunge. If you love the gladiators as much as we do, step into the arena and get ready to compete with these powerful facts about the game-changing gladiator show.

The concept began as a local event.

The seed that blossomed into "American Gladiators" first sprang up among the iron workers of Erie, Pennsylvania. The games are the brainchild of former iron worker and professional arm wrestler Dann Carr, who ran a Pennsylvania sports center through the 1980s and '90s. Sometime in the early 1970s, Carr had the idea to create a statewide event called the Hard Hat Olympics, which ran throughout the 1970s and '80s. Enlisting the help of his sports center colleague Donny Plonski along with Elvis impersonator and promoter John Ferraro, Carr rolled out the first incarnation of what would become "American Gladiators," a youth center fundraiser modeled after the gladiator events that once took place in the Colosseum with Rust Belt everymen as competitors.

The event was held 1983 at Erie Tech High School, allegedly with thousands of fans in attendance. But the performance-minded Ferraro had a wider vision, and with designs on pitching the whole thing to Hollywood, he added the theatrical touch of music and brought in a film crew. As Ferraro told Sports Illustrated, "It was almost like when you see the burning bush. I mean, I saw this thing. Even though I had only done the one small event in Erie, I saw what 'American Gladiators' could be." Years later, Ferraro got the opportunity to make his big pitch, presenting the idea to Samuel Goldwyn, Jr. When Goldwyn suggested the idea was better suited to the small screen, the story almost began to write itself.

The pilot was a fiasco.

By all accounts, the show's original pilot episode was a notoriously terrible experience for everyone involved. Dick Askin, the Samuel Goldwyn Television president who oversaw turning the series into a reality, described the pilot as a "fiasco" in an interview with the Archive of American Television, noting, "It was a learning experience for all of us." Echoing the sentiment, Gemini — one of the original gladiators — described the experience as "horrible" to Sports Illustrated. For the episode, contestants were paid $500 for a day's work. What was meant to be a four-hour shoot turned into an overnight debacle, with the production crew heading home around 6 a.m. the next day. Afterward, Askin said, "It was obvious that we had no clue what the show is, what we were doing ... I mean, we knew nothing."

The shooting location, Los Angeles Equestrian Center, didn't give them enough room to properly pull off the "American Gladiators" vision, and the arena was filled with manure. And according to Gemini, the cast found Johnny Ferraro's commitment to cosplaying Elvis at all times a bit of a shocker. Elvis glasses notwithstanding, Ferraro himself called the pilot a "schlock" job in TIME, admitting that the over-the-top costumes and phony personalities they forced on the gladiators didn't help. When the bad pilot was ultimately scrapped and the series was reworked to focus on the more competitive angle rather than a theatrical one, "American Gladiators" as we know it was born.

They used a plywood audience for the first season

During the peak of the Covid pandemic, sporting events and concerts alike were often forced to resort to using substitute audiences, sometimes with the aid of CGI. But fake audiences are nothing new, as the cast of "American Gladiators" Season 1 can attest. During the show's first season, the "Gladiators" phenomenon had not yet taken off, which meant the producers simply didn't have enough audience members to fill their stadium up all the way. According to both Dick Askin and Nitro, the show's solution was to create their own. To fill those balcony seats, the show's producers used plywood and quite literally painted faces on it, creating an analog version of a CGI audience. A few eagle-eyed viewers have even spotted these odd-looking audience members in some of the show's early tapings, with some comparing them to Mii characters from Nintendo Wii or even the digital audience that shows up in the "Black Mirror" episode "Fifteen Million Merits."

The concept originally included an executioner

According to the cast and crew of "American Gladiators," it took some time to work out exactly what type of show they wanted to present. And apparently, the original concept meant leaning in hard to the gladiatorial theme. According to Ferraro, they didn't originally have a typical sports referee. Instead, Ferraro said, "The 'referee' was an executioner — a guy with a black hood giving the thumbs up or down" to let a player know if they would go on or be disqualified.

The concept of a thumbs-up or thumbs-down in the gladiator arena is historically accurate, although scholars are at odds over whether the thumbs-up was good or bad and vice versa. Although swapping a ref for an executioner would have technically been thematically accurate, it does seem a bit overly theatrical, especially given the addition of the black hood. When the guy in the Elvis suit thinks it's over the top, it's safe to say it's a doomed idea, so the hood was scrapped before the series premiered.

The original time slots were terrible

Younger generations who have grown up in a world of on-demand and streaming television simply don't know the pain of having to be home at the exact time a favorite show is scheduled to come on. And for some fans of "American Gladiators," watching their favorite gladiator step into the arena could require tuning in at odd times, since the show wasn't originally picked up by a major network.

Askin learned about the "Gladiators" project on his first day on the job at Samuel-Goldwyn from a four-page brochure with no words, just pictures of competitors performing at events. At that point, a producer had optioned the name from Ferraro, but it hadn't gone any further, so Askin decided to option the series for development. "Gladiators" had to be sold in syndication from one market to the next, often taking the second or third station in the market. What they ended up with after pitching all those markets was a "patched-together" lineup of air times – which essentially meant what time it aired depended on which area of the country you happened to be located in at the moment. When the producer of New York's WNBC picked up the show, telling Askin she thought he had a hit on his hands, she scheduled it two shows after "Saturday Night Live," which meant it would air at 2 a.m. Luckily, the show caught on anyway, and all of those air times gradually began to improve.

The job came with some serious perks

After their time on the show, many of the gladiators went back to living pretty humble lives. According to Sports Illustrated, Nitro went on to write about his experience and put on a 5K fun run; Laser got into the gym business; Gemini became a fitness consultant; Malibu went into graphic design, and Blaze became a substitute teacher. But during their "Gladiator" years, these guys were living the high life, and they knew it. Ice, who went into the self-help seminar business after returning her pugil stick, managed to rack up a handful of IMDb credits on shows like "The Outer Limits" and "Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman." She also got invited to Bruce Springsteen's place, noting that he has an especially impressive gym.

Nitro recalled being out at dinner one night when Steve Martin approached him and invited him back to his table to meet Dustin Hoffman and his wife. He went on to recount a swanky billionaire's party where Tony Bennett was performing, Cristal was on tap, and three U.S. presidents and Merv Griffin were on the guest list. And while they were on tour, the gladiators often rode in Whitney Houston's tour bus, occasionally running into MC Hammer as the tours crossed paths at venues.

They were asked to script it

Even after the production studio figured out the right angle for the show, they had a hard time getting their markets to understand it. And according to Dick Askin's chat with the Archive of American Television, one of the early decisions they had to face was whether or not to script the show.

After filming the pilot, Askin began shopping the show around to get a series order that could help pay for the first season. When he pitched the idea to the head of Fox station group, he was given a pretty sweet offer for an on-air Season 1 with a double run — an order Askin calls the "golden grail of syndication." But there was a catch so big he would ultimately be forced to leave the offer on the table — Fox would only pick it up if Goldwyn dropped the physical competition element and scripted the show, specifically citing the WWF (later known as the WWE) as an example. Askin knew this wouldn't work and walked away from the deal, which meant they ended up having to shop the show from market to market. But he stuck to his guns, believing that filling the show with cheesy costumes and "corny dialogue" would have compromised its heart. "We decided it had to be legitimate," Askin emphasized.

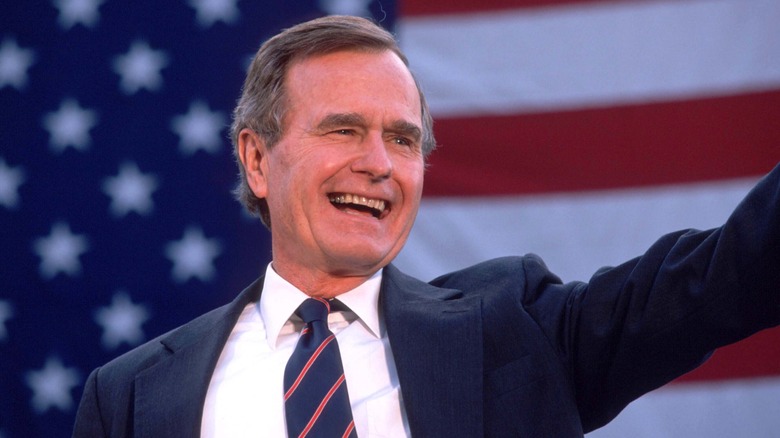

The show had two presidential endorsements

Despite the show's wacky lineup of syndicated air times, "American Gladiators" started to see an increase in publicity and word-of-mouth viewership. As the series picked up a wider audience, they were able to invest more in the production, which added to the overall quality of the show and brought in even more viewers. Over the course of the show's first five years, Askin said they saw a significant increase in both quality and viewership each year. But the show also got a few "national breaks" including the endorsement of not one but two U.S. presidents.

The first would come from President George H.W. Bush, who somewhat inadvertently gave the show a plug by mentioning it during his 1992 RNC speech accepting the Republican nomination. During the speech, Bush remarked that Americans are "tired of people in Washington acting like they're candidates for the next episode of 'American Gladiators.'" Apparently, his successor wasn't tired of that at all, because Bill Clinton would later cite the show as one of his favorite White House pastimes to enjoy with his daughter Chelsea. According to People, Clinton said he initially found the show too campy, but it grew on him. Hillary, on the other hand, "thinks it's awful."

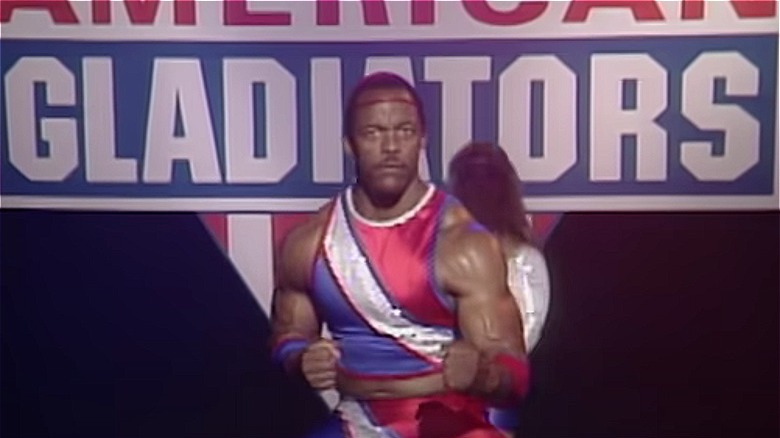

It was designed to give average joes a chance to shine

Even after "American Gladiators" skyrocketed to national fame, it never let go of its blue-collar everyman roots. The team of gladiators included professional athletes like former pro football players Nitro and Gemini. Fitness experts, martial artists, and Olympians were all on deck as well. But after the pilot took a wrong turn, the producers decided to inject the series with heart, bringing in highly competitive weekend warriors just living everyday lives like the rest of us working schmucks.

Emphasizing that many of the gladiators "weren't nearly as good as some of the contestants," Askin said producers were interested in presenting contestants with an interesting story. "We wanted them to be able to tell their story," he explained. Like many unscripted shows to follow suit, "Gladiators" would show contestants' families, talk about their jobs, and most importantly, humanize them. Some of the contestants were teachers or Gulf War veterans. Askin said, "It was that humanity coupled with legitimate competition that really drove the show." This secret sauce proved so effective that it was considered essential to the show's 2008 revival, meant to highlight everyday heroes by letting them tell their personal stories.

Drug use was once rampant on the series

Anyone who is old enough to remember the 1980s knows how ubiquitous anti-drug messaging was during this era, and "American Gladiators" was no exception. But as it turns out, the cast wasn't as squeaky clean as folks might have wanted to believe. "Gladiator" business is a painful business, and contenders were often legitimately injured on the job. During Laser's time as a gladiator, he underwent 11 surgeries in just seven years. Since missing an episode meant missing out on a payday, the gladiators found a way to work, even if it meant shoveling pain pills down and sucking it up. As Dallas put it in Sports Illustrated, "If you got hurt, they did fix you. You just didn't get paid while you were out."

In their Sports Illustrated interview, Nitro and Laser recount taking copious painkillers so they could pass tests and get the green light for an episode. In a now-archived Maxim feature, Zap called it a "free-for-all" — one that landed her in rehab. Although the gladiators were at one point tested for steroids, Nitro said, "Nobody ever told us what those results were." Nitro was certainly using them, later recounting the serious long-term health problems he suffered as a result. As it turns out, drugs weren't the only party favors in the gladiator barracks, with Hawk noting that many of the gladiators were cozying up off-camera.

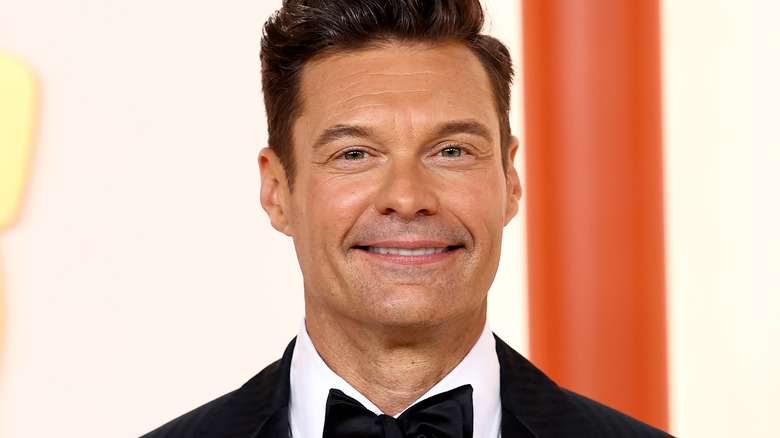

Ryan Seacrest got his start on the kids' version

These days, Ryan Seacrest is a household name. He has hosted dozens of shows, most notably "American Idol," "E! News," and "Live with Kelly & Ryan." But many fans of Seacrest don't realize he got his start on the kids' version of "American Gladiators." Because apparently, someone thought it was a good idea to do a children's version of a show where contestants regularly suffer herniated discs and shoulder injuries, "Gladiators 2000" was born under a division of MTV networks, airing from 1994 through 1996 on Saturday mornings.

Discussing the show on "Live," Seacrest would later refer to it as "educational gladiating." The series presented a kid version of many original gladiator games, weaving in health and fitness education elements like trivia questions and the food pyramid. Gladiators from the original series would even appear on the show to help with some of the educational content — at one point, Sky even showed up to give toothbrushing lessons. Events included Assault, Swingshot, and The Wall, among others, all notably less brutal than the versions played by their adult counterparts. The then-19-year-old Seacrest hosted the series throughout its short run, notably using the catchphrase, "See ya next time! Bye Bye!" After meeting Merv Griffin through his work on the show, his career took off just as "Gladiators 2000" fell flat.

The gladiators went on tour

With a show as successful as "American Gladiators," it makes sense that the producers would want to milk that cash cow for everything she was worth. And that's exactly what happened in 1991 when the show's popularity was peaking, and Ferraro had the brilliant idea to take the gladiators on the road.

Ferraro got the idea when he learned that colleges were hosting their own gladiator events and began asking the show to perform on campus. Happy to oblige, Ferraro approached the production company, but they weren't having it. Ferraro told Sports Illustrated, "They fought me tooth and nail, so I started putting it together without them." They brought in an organizer and the owner of the Ringling Bros. circus to start booking large venues. The result of their labor was a 7-Eleven-sponsored tour in 150 cities across the country, with many stops booked in 20,000-person arenas.

Ahead of each show, a call for contestants would go out in local papers and TV stations, with some bringing in thousands of potential contestants. And like "American Idol," most auditioners would get eliminated almost immediately with a rigorous challenge — a whopping 50 fingertip push-ups in less than a minute. As Ohio contestant Vince Pecchia would later tell writer Troy Benjamin, even getting to the competition stage was enough to grant someone local hero status.