5 Things Hulu's Boston Strangler Gets Wrong (& 5 It Gets Right) About The Real Story

The following article discusses sexual assault and murder in graphic detail and might be upsetting to some readers. If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

The true crime trend shows no signs of slowing down, whether in the form of podcasts, TV shows, or feature films, and whether the cases are rendered as documentaries or fictionalizations. With series like "Dahmer" and movies like "The Good Nurse," Netflix has long been the dominant force in the popular genre, but Hulu is looking to catch up with "Boston Strangler," its retelling of one of the most notorious — and still controversial — crime sprees of the 20th century.

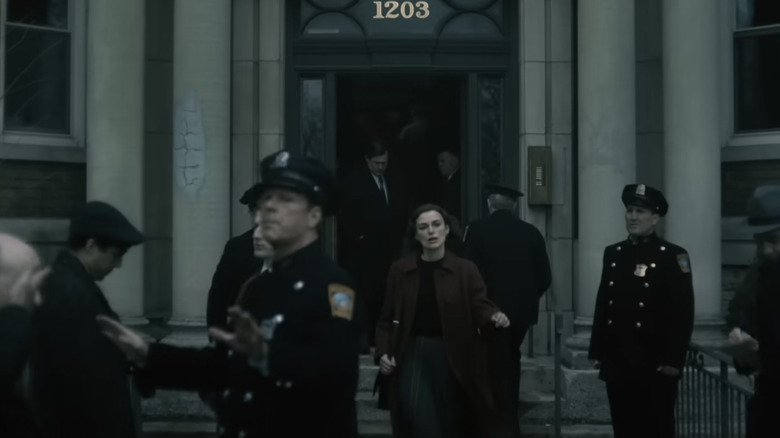

A previous version of the Strangler's story was made into a film almost immediately after the extremely particular and brutal slayings stopped in 1968. That film, "The Boston Strangler," starring Tony Curtis and Henry Fonda, focused on detectives' efforts to identify and apprehend the culprit. 2023's "Boston Stranger," starring Keira Knightley and Carrie Coon, changes the perspective to that of journalists covering the story for the local papers. Not only does this update paint a broader and more detailed picture of city gripped by fear, it has the luxury of more time. Since 1968, new discoveries have been made about the murders, which allows Hulu's "Boston Strangler" to come to a more plausible conclusion. Still, it's tough to fit 60 years of reporting and police work into a two-hour drama, so despite its admirable faithfulness to the truth, "Boston Strangler" is nevertheless inspired by (and not strictly) a true story.

Right: McLaughlin and Cole really did break the story

The protagonist of "Boston Strangler" is Loretta McLaughlin (Knightley), a married mother of three who works at the Record American, where she's unhappily reviewing toasters for the lifestyle section when we meet her. She begs for more substantial assignments but is rebuffed by her male boss — that is, until she beats the rest of the city to the punch about the fact that there might be a serial killer on the loose. Eventually she gets permission to pursue the story, but she's assigned a partner and mentor of sorts in Jean Cole (Coon). At first, Loretta resents being tied to Jean, though they become and friends before long. Notably, we watch as Loretta comes up with the name "Boston Strangler" at her typewriter.

This is all largely true. Loretta McLaughlin and Jean Cole are the real names of the two reporters who wrote a four-part series about the Boston Strangler for the Record American. McLaughlin fought to get the story, which Cole joined later. Just as in the movie, McLaughlin and Cole were enterprising and extremely good at their jobs despite the subtle and overt sexism they faced. They became characters in the story they were covering when headlines such as "Two Girl Reporters Analyze Strangler" ran alongside their headshots. The post-script titles that sum up the careers McLaughlin and Cole went on to have (as well as McLaughlin's divorce) are meticulously researched, too. There's no proof they ever butted heads as they do in "Boston Strangler," though.

Wrong: The police bought into the multiple stranglers theory first

One of the major sources of tension in "Boston Strangler" is the souring relationship between reporters and police. Cole teaches McLaughlin how to establish trust with detectives and how to gain access to crime scenes and documents, but when the murders remain unsolved and the killer continues to strike, the Record American begins to print news that's critical of law enforcement. McLaughlin — frustrated by shoddy police work — accuses detectives of botching the case. It's insinuated that departments failed to cooperate and good leads were overlooked. The Record American did run negative stories about the investigation, and there was bad blood between the papers and the police, but it mostly had to do with red tape, politics, and differences of opinion.

Loretta, who had coined the moniker "Boston Strangler," stuck with the single killer theory even after the victims' profiles changed, while the police had preferred the idea of multiple killers or copycats. The film makes it seem as though Boston police ignored or turned down help, for example, from the NYPD regarding a related crime. However, in addition to possible candidates like ex-boyfriends, detectives did look into Charles Terry (whose name is changed for the movie), the murderer of Zenovia Clegg. Often, evidence was lacking or outside officers weren't able to interview suspects. Internal infighting arose when Attorney General Brooke seized control and appointed his inexperienced assistant AG Bottomly (a former real estate lawyer) to oversee the newly created Strangler Task Force. The move was seen as political opportunism. The epiphany that McLaughlin and Cole have at the film's end more closely resembles detectives' working theory throughout.

Right: The Strangler's MO is generally accurate

"Boston Strangler" does an effective job of summarizing the scope and specificity of the 13 potentially related murders that were committed between June of 1962 and January of 1964. The names and ages of the victims are factual. So are most of the dates of their deaths and the order in which they occurred, as well as many of the horrific details. Generally speaking, there weren't signs of forced entry, which indicated to police that the killer was either familiar to the victims or assuming an identity (like that of a painter or maintenance worker). Typically, ligatures were found in decorative bows around victims' necks and their bodies were often stripped and arranged so as to rob them of their dignity in death. The Strangler did seem to taunt detectives; in one case, he left a New Year's Eve card at the crime scene.

More to the point, the film captures the most perplexing part of the Boston Strangler mystery. The Strangler's modus operandi seems to have changed halfway through. The first five victims are correctly shown to be white women over the age of fifty who lived alone (a sixth victim who died by heart attack would be added to the number later). During this time, psychologists imagined that the killer might be a violent pervert who hated his mother. Then, the supposed Strangler killed Sophie Clark, a 20-year-old Black woman who shared an apartment with roommates, followed by several more young women, one of whom was pregnant. Experts were split about whether a serial killer's motives could evolve in this way.

Wrong: The cases weren't so neatly connected

While "Boston Strangler" gets the vast majority of its facts right, there are minor differences between the version of the story that appears in police reports and newspapers and the version that appears on screen. Most of these discrepancies probably exist for the sake of narrative efficiency, but they're worth pointing out, especially for the home viewer trying to solve the case along with McLaughlin and Cole.

In both the film and real life, the Strangler's first victim was 56-year-old Anna Slesers. Knightley's McLaughlin mentions that the first three victims were all killed with stockings tied in a double-hitched knot. The detective who was on the scene tries to write off Slesers' death as a suicide. It's implied that all the victims were strangled, sexually assaulted with foreign objects, and posed.

Really, Slesers' son discovered her body strangled with the sash of her robe, which he reported as a potential suicide. Detectives immediately ruled that out, having noticed physical evidence of sexual assault. They also observed that the apartment had been ransacked but nothing had been taken. Though (if viewers look closely) documents in "Boston Strangler" are more accurate, the film makes it seem as though stockings were always the murder weapon. However, sometimes the killer (or killers) used bras, scarves, or pillowcases. Two victims were stabbed. Some women had been violated with objects, while semen was found on or near the bodies of others, and some hadn't been sexually violated at all. In some minds, these variances combined with the change in the victims' profiles support the multiple killers theory.

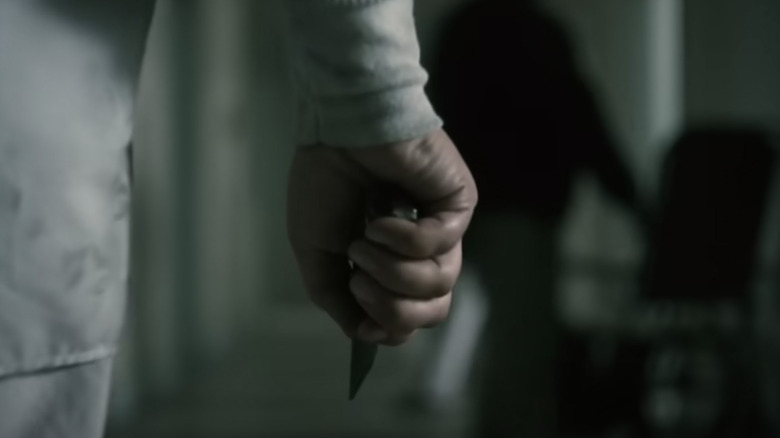

Right: DeSalvo's biography is correct

About halfway through "Boston Strangler," a prime suspect emerges when the name Albert DeSalvo is given to McLaughlin off the record. The 30-something married father of two (played in the movie by David Dastmalchian) has a checkered past and fits the description given by witnesses, who claim a white man with black slicked back hair either said he'd been contracted to do work in their apartments or offered them work as models. DeSalvo is identified as "the green man" and "the measuring man" — a local predator who uses those two cons as a pretext to assault women... only he was incarcerated on unrelated charges during the first wave of killings. Then, McLaughlin and Cole find proof of his early release and DeSalvo confesses to all 11 known Boston Strangler murders plus two additional deaths shortly thereafter.

Though McLaughlin's involvement is exaggerated, DeSalvo's story is as presented (if not worse). He endured a disturbing childhood in which his father would physically abuse his wife and engage in sex acts with prostitutes in front of his children. He'd go on to commit hundreds of assaults, first as the measuring man, then as the green man, most of which came to light after news of his con ran in the paper, prompting other victims to come forward. But he was only ever convicted of minor crimes, not lewd acts (for example, a nine-year-old girl's family decided against pressing charges to protect their daughter), so he wasn't in any of the sex offender databases. DeSalvo was let out early for good behavior, but was sent to Bridgewater Hospital after yet another rape, where he met George Nassar. He confessed to the murders in 1967, but contacted psychiatrist Dr. Ames Robey (not McLaughlin), wanting to talk the day before he was killed in custody in 1973.

Wrong: Other details and events have been fictionalized

Writer-director Matt Ruskin really did his homework as it pertains to McLaughlin, Cole, and DeSalvo, but he took some creative liberties with supporting characters and subplots. While the Record American was a real newspaper (it started out as and returned to being the Boston Herald), Chris Cooper's Jack Maclaine and Robert John Burke's Eddie Holland appear to be composite characters with fictional names. Detectives Conley (Alessandro Nivola) and Doogan seem to be homages to District Attorney Daniel Conley and Sergeant Detective William Doogan, both of whom worked on the case more recently and were instrumental in tying DNA evidence to DeSalvo. The film portrays 22-year-old victim Patricia Bissette as having been pregnant with her boss' child. In the film, he's a toy brand CEO named Gordon Neilson, but he was actually named Jules Rothman, and he and Patricia worked for an engineering company.

"Boston Strangler" briefly takes audiences to New York City and Ann Arbor, Michigan, where eerily similar murders are said to have occurred. Broadly, this is true. As previously mentioned, a suspect was caught and confessed to a strangling in New York, but the film seems to have changed his name from Charles Terry to Paul Dempsey. Later, McLaughlin gets called to Michigan to offer her opinion about six more stranglings there. She and the local brass point to someone named Daniel Marsh, the creepy Harvard educated ex of one of the Boston victims. The Michigan Murders (or Co-Ed Murders) did happen, but an Eastern Michigan University Student named John Norman Collins was convicted for one of them and suspected in many of the rest.

Right: There was a media circus

The city of Boston — especially its women — were in a full-blown panic for the 18 months that the Strangler was on the loose. Chain locks were flying off the shelves and guard dogs were quickly snapped up from the shelters. People refrained from going out and refused to let strangers into their homes. The near mythic tale of the Boston Strangler had already consumed the public, yet once a killer came forward, residents were left with even more uncertainty, and a true crime-ready media circus ensued.

As is shown in the film, a neighbor who'd come into contact with the potential killer chose George Nassar, not Albert DeSalvo, out of a police lineup. Nassar and DeSalvo were in custody together (on more than one occasion), and it was Nassar who introduced DeSalvo to his lawyer, F. Lee Bailey. Bailey's celebrity increased because of the case, and he did write and publish a book on the topic, "The Defense Never Rests." In a 1968 Boston Globe article, Dr. Ames Robey claimed to have overheard another inmate coaching DeSalvo. He was able to accurately describe some aspects that, seemingly, only the killer could've known about, but he repeated mistakes from newspaper reporting in his testimony. He was also shown pictures of crime scenes and fed leading questions by his interrogator, Assistant AG Bottomly, who many felt was out of his league. Because jail cell confessions are quite common and rarely reliable, not everyone felt the mystery of the Boston Strangler had been put to rest.

Wrong: The real reason DeSalvo wasn't charged is more complicated

In Hulu's dramatization, Loretta McLaughlin and Detective Conley strike up a working relationship if not quite a friendship, despite the lack of trust between law enforcement and the media. But near the film's end, an irritated Conley implies that McLaughlin's coverage of DeSalvo is why he's about to get away with murder. "Boston Strangler" makes it seem as though the notoriety manufactured by the press led to F. Lee Bailey's scheme to negotiate with police for a confession that wouldn't be admissible in court. DeSalvo tells all to Bottomly in a recorded interview, but despite his admission of guilt, he's charged with and convicted of lesser crimes and sentenced to life in prison. This is meant to be understood as a failure of the system, which is underscored by McLaughlin's visit to the mother of victim Beverly Samans.

Here, the basic facts about DeSalvo's deal with the prosecution as well as his trial and sentence are all true, but the real reason for the state's actions had less to do with McLaughlin and more to do with legal standards. As the characters in "Boston Strangler" make note of repeatedly, the killer left behind no physical evidence. There was nothing to tie DeSalvo to any of the murders besides his word, which meant a conviction for the 13 purported Boston Strangler murders wasn't assured. DeSalvo was also committed to Bridgewater Psychiatric Hospital at the time and his lawyer, Bailey, planned to mount an insanity defense. The deal in question appears to happen hastily in the movie. In real life, Bottomly didn't interrogate DeSalvo until 1967.

Right: Most of the victims' cases remain unsolved

"Boston Strangler" ends with a new theory about the case and a series of title cards that might register as contradictory. McLaughlin and Cole change their minds about the possibility of multiple killers. They wonder if the first six victims might be the work of one strangler, while the rest might be copycats or disguised crimes of passion. Finally, we learn that — though no one was ever charged with the 13 Boston Strangler murders — DNA evidence proved that Albert DeSalvo did in fact murder the final victim, Mary Sullivan. This summary is as close to the truth as anyone has gotten so far.

Though Loretta McLaughlin believed DeSalvo was the sole Boston Strangler throughout her life (which is a departure from the film), many other experts — including doctors, detectives, authors, and family members — think there's more to the story. Some held that Charles Terry was responsible for the first four to six murders. Some put forth that George Nassar was the real Strangler and that he fed information to a fame-hungry DeSalvo. Some argued multiple killers, including Jules Rothman and other disgruntled exes and lovers (some of whom did fail polygraphs) used the phenomenon of the Strangler to mask their own violent acts. Two such men had been suspects in Mary Sullivan's killing. But in 2013, Boston Police confirmed DNA from DeSalvo (first from a male relative, then from his remains) matched seminal fluid that had been found on Sullivan's body.

Wrong: The truth is even more bizarre

As full of disturbing twists and turns as "Boston Strangler" is, the film leaves out a few of the most bizarre developments in this captivating true crime story. For example, it omits the fact that DeSalvo escaped from Bridgewater with two other inmates after he'd confessed, triggering an area-wide manhunt and renewed public panic. When he was finally caught, he claimed that he'd broken free to protest the conditions at the hospital for the criminally insane. He was transferred to the higher security Walpole State Prison.

DeSalvo also learned how to make jewelry and — quite morbidly — wanted to sell "Strangler chokers." Some of his pieces were displayed in the prison lobby.

Though the film treads lightly upon this conspiracy theory, George Nassar and Albert DeSalvo were at Walpole together at the time of his death by stabbing. The very psychiatrist who favored Nassar for the killer, Dr. Ames Robey, was coming to hear what was widely expected to be DeSalvo's official retraction of guilt when he was murdered. DeSalvo's rumored autobiography was conveniently missing, and his death was ultimately blamed on a drug deal gone wrong.