Movie Adaptations Of Books Hated By The Authors But Loved By Critics

"The book was better." It's what we always say and hear when discussing movies that have been adapted from or are otherwise based on books. And the vast majority of the time, it's an accurate statement — movies are at a disadvantage by nature of their medium when it comes to being able to properly bring a story from page to screen. That being said, most authors tend to be content as long as the movie based on their book is at least good, regardless of how well it is or isn't able to fully convey everything they were trying to express in their original written text.

Remarkably, that isn't always the case. There are a number of books adapted into films that have turned out to be certified classics — and yet, for one reason or another, the authors of the original material just weren't thrilled with what they saw. Sometimes it's a personal gripe; other times it seems to stem from some aspect of the business transaction that went sour. In a few cases, the author was even initially involved in the movie but still ended up dissatisfied with the direction the project ended up going in. One particularly infamous example even sees the original author as the credited screenwriter for the movie — and yet they still hate the finished product.

Cool Hand Luke

You won't be blamed if you weren't aware that "Cool Hand Luke" was based on a book. Donn Pearce's 1965 book was quickly overshadowed by the iconic 1967 Paul Newman film, with the movie having the more enduring legacy. Both are about a Florida prison inmate named Luke who works on a chain gang. As far as how they differ — and why Pearce isn't a big fan of the movie — you need only examine the film's most legendary quote, "What we have here is a failure to communicate."

In an interview with Esquire, Pearce didn't mince words about the quote. He called it "a stupid ****ing line" and explained that such characters wouldn't use such a flowery phrase. He was also unwilling to even concede that Newman did a good job in the role, saying that the actor wasn't believable as a street-tough convict, lacked an imposing physical frame, and was "simply too small to play a man like Luke." What's interesting is that Pearce co-wrote the screenplay for the film and even earned an Oscar nomination for doing so. But he also says he was treated poorly on set and saw very little money relative to the movie's success, surely playing a part in his eventual souring on the movie.

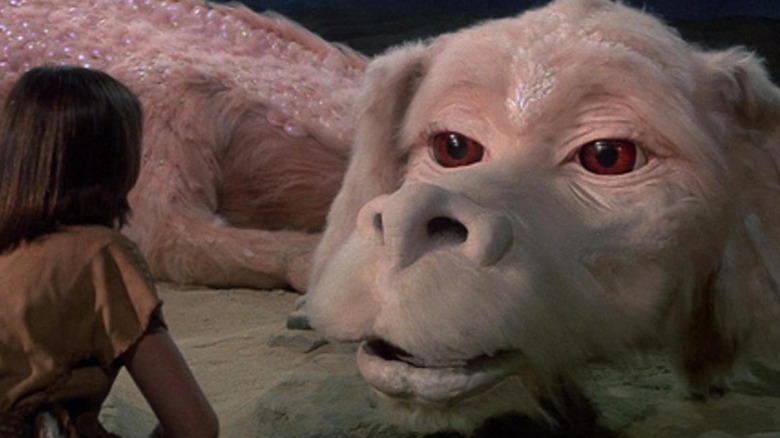

The NeverEnding Story

For kids of a certain age, "The NeverEnding Story" was one of those childhood-defining films that people watched on repeat until the VHS tape wore out. It wisely features dual child protagonists as well as a child damsel in distress, and its incredible practical effects and puppet work helped it to age remarkably well for a movie from 1984. The story follows a bullied kid (Barret Oliver) who hides in his school's dusty storage room and reads the titular tale about a mystical land called Fantasia, soon realizing that he himself is somehow both part of the story and also affecting the book in real-time.

One person who didn't find it endearing was Michael Ende, who wrote the 1979 book that the movie is based on. According to People, the month of the movie's initial release in Germany, Ende was already ragging on it. "The makers of the film simply did not understand the book at all," Ende said. He went on to call the film "revolting." Though Ende was involved in the early phases of the production, he says that director Wolfgang Petersen rewrote the screenplay without Ende's knowledge after Ende had already okayed the original version. He said he was "horrified" by the final script.

V for Vendetta

Famed comic book writer Alan Moore has always had a prickly relationship with Hollywood, and that's probably putting it mildly. More crucially, he has hated basically every movie that has ever been adapted from one of his comics — including "From Hell," "Watchmen," and "The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen" — and has never been remotely shy about saying so.

But "V for Vendetta" is thus far the most critically acclaimed film adaptation of one of his works, the story of a masked terrorist who uses extreme measures to battle against a version of London that has become a fascist police state. As he explained in an interview with journalist Ian Winterton, so disgusted was Moore by this point at the way Hollywood treated his stories that he demanded his name not be included in any future adaptations of his work, a practice that started with 2009's "Watchmen."

As for his issues with "Vendetta" specifically, Moore said he didn't like the way the political message was shifted to apply to George W. Bush-era America, pointing out how important anarchy and fascism were to the original story and that the movie never even uses either of those words.

Mary Poppins

The story of how Walt Disney chased the rights to adapt the "Mary Poppins" series of books into a movie for years as author P.L. Travers repeatedly turned him down was later turned into a movie by Disney itself. And while "Saving Mr. Banks" definitely showed glimpses of Travers being appalled at what her story was turning into at the hands of Disney, it definitely softened the real-life author's true reaction to the original film.

In a Salon feature about "Saving Mr. Banks" and the true story that inspired it, it's revealed that Walt Disney pestered Travers for a whopping 15 years to get her to sign off on a "Mary Poppins" movie. Had money not gotten tight for Travers, she likely would've continued to turn him down indefinitely, but she needed the cash and so she finally relented. One of the most famous stories about Travers' feelings toward the "Mary Poppins" movie is that she hated it so much that she openly cried at the premiere. Despite the fact that "Saving Mr. Banks" reframes those tears as tears of joy, Travers was anything but happy at what Disney had done to her story.

As Vulture describes when referencing the biography "Mary Poppins, She Wrote: The Life of P.L. Travers," Disney was embarrassed that Travers was so openly upset at the premiere — a premiere, by the way, that she wasn't even initially invited to.

Forrest Gump

The general consensus on "Forrest Gump" has leaned a bit more negative in recent years, spurred on by damning reappraisals from outlets like IndieWire and LA Weekly. But there's no denying that it was a huge critical and commercial success at the time of its release, going on to win a slew of Oscars, including Best Picture. Telling the story of a man with indeterminate mental and social struggles who ends up inadvertently shaping the course of American history, "Forrest Gump" is based on the book of the same name by author Winston Groom. And Groom's feelings about the movie are complicated at best.

In a New York Times piece on the author, Groom complained that the movie smooths out too many of the character's "rough edges" that make the story and his journey more interesting. He disagreed with the casting, too, preferring John Goodman or a similarly more physically imposing actor over Tom Hanks. Things get worse when clever Hollywood accounting made it seem as though the massively successful movie hadn't actually made a profit, which meant that the studio wouldn't have to make good on the 3% of the net profits he was promised and forced him to take the studio to court (via the Oklahoma City Journal Record).

Groom seemed to make his feelings on the whole fiasco pretty clear when he wrote the sequel novel, "Gump & Co.," and had Forrest proclaim "don't never let nobody make a movie of your life's story" in the very first paragraph.

The Shining

What's fascinating about Stephen King repeatedly ragging on the movie "The Shining" over the decades is that there is no shortage of really bad films based on his books. So the fact that one of his novels was adapted into one of the most acclaimed and influential horror movies ever made should make him feel pretty good. In defense of King's criticisms of the film, "The Shining" is a deeply personal story for him. In the book "The Stephen King Companion" (via Den of Geek), King explained that one of the impetuses of the story came from him realizing that he "was horrified by [his] occasional feelings of real antagonism toward [his] children." So there's a lot more going on here than simply a story he wrote being turned into a film.

One of King's frequent complaints is that the film version of Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) is already unhinged from the start of the film and that his journey to becoming a man who could let the sinister influences of the Overlook Hotel transform him into someone who wants to murder his wife and child is a big part of the novel and is best when it occurs more slowly and gradually. King has also said that Stanley Kubrick's take on the story is far too cold and is a clear example of style over substance, conceding that the film features striking visual imagery but likens it to "a beautiful car that had no engine in it."

Das Boot

Most recently, 1973 novel "Das Boot" has been adapted into a well-received German television series that debuted in 2018. But the most famous version of the story is definitely the 1981 film, another page-to-screen adaptation from filmmaker Wolfgang Petersen. The original book is fictional but was heavily inspired by author Lothar-Günther Buchheim's experiences as a journalist who spent time on multiple German submarines during World War II.

According to The New European, Buccheim was notorious for being an extremely abrasive and pessimistic figure. The feature goes on to explain that, like with "The NeverEnding Story," Buccheim was initially asked to work on the movie version of "Das Boot" only to be pushed out by Peterson, who helped himself to full creative control. The ever-outspoken Buccheim was very loud with his critical stance on the screen adaptation, with his major sticking points being its lack of historical accuracy and the fact that it was turned into yet another example of Hollywood glorifying and celebrating violence — while the point of his novel was the condemnation of those very things.

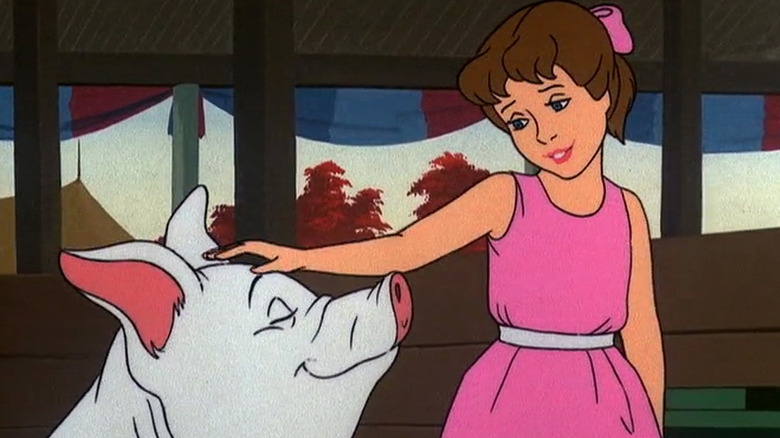

Charlotte's Web (1973)

There have been multiple adaptations of E.B. White's beloved children's book "Charlotte's Web," from film to stage to even video games. But most would agree that the definitive one is the 1973 animated feature film produced by Hanna-Barbera. It tells the bittersweet tale of a pig named Wilbur (Henry Gibson) who learns hard lessons about life both by virtue of learning he is intended for slaughter and in befriending a dying spider named Charlotte (Debbie Reynolds).

Though it got some criticism for being underwhelming in the visual department — as was somewhat typical of Hanna-Barbera's work — the acting was highly praised and the movie was ultimately well-received. White, on the other hand, was almost entirely negative on the whole thing — both the behind-the-scenes drama of its production to the quality of the final product. In letters from the author published by his friend Gene Deitch, White spoke of the nightmare of having to deal with Hanna-Barbera and resented the fact that the movie's plot was constantly interrupted by saccharine musical numbers. Ultimately, he summed us the movie as a "travesty," and opined, "that's what you get for getting embroiled in Hollywood."

Breakfast at Tiffany's

What about "Breakfast at Tiffany's"? Most people kind of like it — other than the extremely poorly aged performance of Mickey Rooney as Mr. Yunioshi, the Blake Edwards-directed, Audrey Hepburn-starring romantic comedy is an American classic that continues to be discussed and referenced to this day. In it, Hepburn plays Holly Golightly, an escort looking to bag a wealthy older man, and she thinks she has found exactly that in Paul Varjak (George Peppard).

The original book of the same name that the movie adapts is written by none other than Truman Capote, and he was certainly not going to hold back if he felt the film didn't do right by his story. Sure enough, in an interview with Playboy, Capote took issue with everything from the movie's tone to its casting and portrayal of Holly Golightly. He said that Holly was "a tough character, not an Audrey Hepburn type at all" and that "the film became a mawkish valentine to New York City and Holly and, as a result, was thin and pretty, whereas it should have been rich and ugly."

According to biographer and journalist Barry Paris (via The Vintage News), Capote wanted Marilyn Monroe to play the lead in the film and remarked that the studio "double-crossed [him] in every way" by going with Hepburn instead.

Death Wish (1974)

While not a critically acclaimed movie per se, especially at the time of its release, the original "Death Wish" has since seen enough positive reappraisals that is critical consensus now falls firmly in positive territory. The less said about the long line of dreadful sequels and the abysmal 2018 Eli Roth-directed remake, the better, but the Charles Bronson original was a crowd-pleasing exploitation-era action thriller about a man named Paul Kersey who turns to violent vigilante justice after his family is attacked in their home.

The "crowd-pleasing" part is precisely what the author of the original book had an issue with. Brian Garfield's 1972 novel was also a tale of bloody revenge, but he wanted readers to be shocked by Paul's actions and for the moral of the story to be that answering violence with violence is never the answer. Taking what he saw as a cautionary tale about violence and turning it into the kind of movie that has audiences cheering on violence is the exact opposite of what Garfield had intended. The author even wrote a follow-up book called "Death Sentence" in 1975, about Paul regretting and rethinking his actions, as a direct response to the "Death Wish" movie. Unsurprisingly, "Death Sentence" wasn't used as source material for any of the four "Death Wish" sequels or the remake.

A Clockwork Orange

Stanley Kubrick ruffled a lot of feathers during his filmmaking career, particularly among the authors whose books he adapted into movies. Not only was Stephen King unhappy with what Kubrick did with "The Shining," but "A Clockwork Orange" author Anthony Burgess also took issue with what Kubrick did to his story when bringing it to the big screen. What's interesting here is that Burgess was initially a champion for the film — though, incidentally, that's part of where things ended up going south in terms of Burgess's relationship with the movie.

According to the book "Sexplosion" (excerpted in The Wrap), Burgess initially claimed to be a fan of the film and defended from bad press and against accusations of it glorifying violence. However, Burgess soon found that he was going it alone in that regard, as Kubrick stayed quiet for the first leg of the publicity tour and never stepped forward to back up Burgess in defending his own movie. This left Burgess feeling burned and led him to begin rethinking his feelings about both Kubrick and the film itself. It didn't help matters that he wasn't paid more than a few hundred dollars for his involvement. As more and more people began to speak out against the movie and point out that it was allegedly inspiring real-life violence, the blowback began to reach Burgess' book as well — and he began to further resent the movie for the way it was now retroactively affecting his book in a negative way. That is, if people even bothered making themselves aware of the book at all. "Kubrick's achievement swallowed mine, whole," Burgess lamented.

Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory

Author Roald Dahl said and did some things in his life that have severely tarnished his legacy and overshadowed his work (per Time magazine). With that in mind, when looking at something like his criticisms of the first film adaptation of his story "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory," it's easy to take a "who cares what he had to say about anything?" attitude.

Nevertheless, it's still worth exploring his complicated relationship to the making of 1971's "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory" and his subsequent rejection of the final product. Though he got sole screenwriting credit on the film, it has since been well-documented that Dahl's initial script was extensively retooled and rewritten to the point where it scarcely resembled his original draft (per The Guardian). Beyond not recognizing the movie he supposedly wrote, Dahl also took issue with casting American Gene Wilder as Wonka rather than an English actor, the shifting of the title role from Charlie to Wonka, the various plot additions, and the movie's upbeat songs and score.

Would Dahl have preferred the Tim Burton version that was released in 2005 and claimed to be much more faithful to the original book? It's impossible to say — but for what it's worth, Gene Wilder called it an "insult" (per Entertainment Weekly).

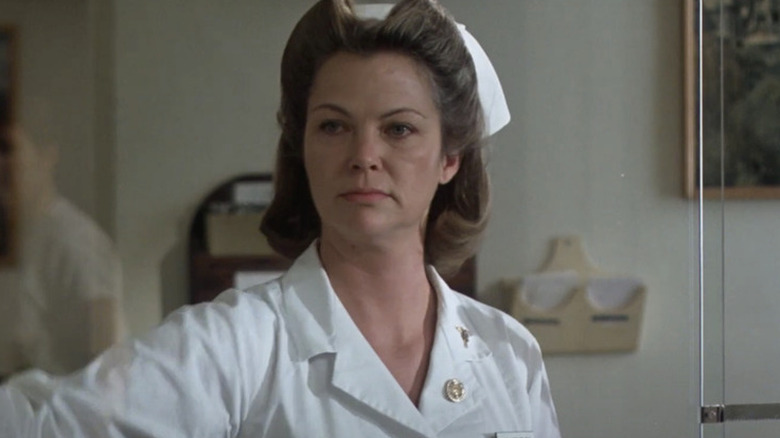

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

Another instance of Jack Nicholson finding himself in an acclaimed movie that wasn't very well-liked by the author who wrote the original book, it might seem hard to imagine what Ken Kesey could've possibly disliked about the film version of "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest." The Rotten Tomatoes consensus calls it "a film of outsized power" and points out what a volatile rivalry Nicholson and Louise Fletcher made out of the relationship between Randle McMurphy and Nurse Ratched, respectively — rightly earning both of them Oscar wins for their performances.

But Kesey didn't see the powerful, complex film about mental health that most people saw. Instead, as reported by NPR, he saw a movie that had more in common with the goofy sitcom "Hogan's Heroes" than prestige Hollywood filmmaking. He was so disappointed by the movie — after being involved in the production's early stages, he exited over creative differences — that he claimed to have never watched it or even wanted to.