What Emancipation Doesn't Tell You About The True Story

The following article includes discussions of slavery that may be uncomfortable for some readers.

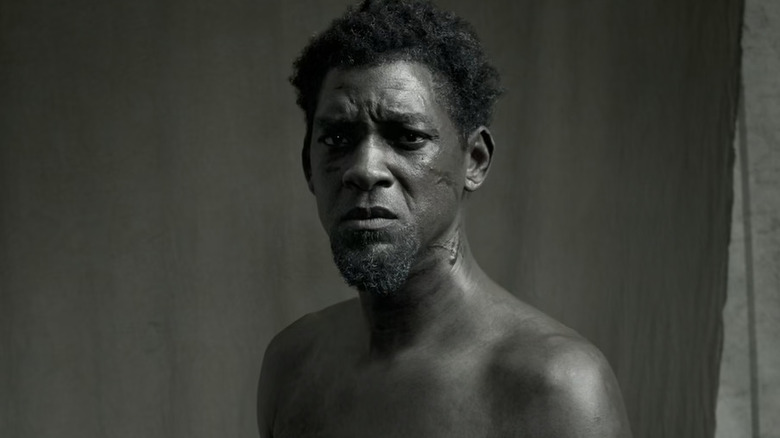

Directed by Antoine Fuqua and starring Will Smith, the Apple TV+ original movie "Emancipation" is inspired by "The Scourged Back" photo, one of the most famous photographs from the Civil War (via Deadline). The film recounts the incredible true story of a man in the photo known as "Whipped Peter," who escaped slavery in March 1863 after surviving a series of beatings so severe that his entire back was covered in a web of keloid scarring (per History).

Eventually, his photograph and an account of his incredible journey to freedom spread across the nation and captivated millions. Thanks to its undeniable evidence of slavery's cruelty, Peter's story helped to bring to light the true nature of the brutality of the slave trade in America. Galvanizing support for the movement to abolish slavery and for the Union, Peter became a symbol for more than just the violence that was perpetuated against Black men, women, and children, but for the strength, courage, and determination of slaves who fought for freedom against all odds. While "Emancipation" is a moving portrayal of Peter's struggle, there is still so much more to the story that the movie doesn't tell you. And while even we don't have room to explore every facet of the historical account, we hope that we can expose our readers to a bit more of the true story surrounding "Emancipation."

Who was Whipped Peter?

While "Emancipation" is based on the remarkable true story of a man known as "Whipped Peter," made famous by an iconic photograph taken in 1863, there has been much debate as to his real name. Much is unknown about the man's life beyond what he revealed in his testimony during his examination, as noted by David Silkenat of the University of Edinburgh. The original feature first published in Harper's Weekly listed his name as Gordon (via History), so some believe Peter may have been a different man entirely; the New-York Daily Tribune reported, however, that both Gordon and Peter were two separate Black men featured in the same Harper's issue. The feature is widely accepted as the true account of Peter's experiences. In the film, Gordon is one of Peter's fellow escaped slaves, played by Gilbert Owuor.

Unlike in the film, however, Peter actually spoke very little English. While the movie gives the slaves heavy accents, in reality, the plantation owners in Louisiana typically hailed from France and the slaves all spoke fluent French. Peter's plantation, though, was owned by John Lyons, who hailed from Ireland. On Lyons' plantation, Peter was abused, prompting him to flee to Baton Rouge, where he was eventually photographed by Union doctors. While some details are still up for debate, there's no doubt that he endured unfathomable hardship in slavery and beyond, and thanks to the photograph that made him and his plight famous, his impact on history is immeasurable.

Peter's recovery from the beatings

In the film, when Peter is discovered by Union forces — specifically the Native Guard led by Andre Cailloux (Mustafa Shakir) — he is taken to a camp to recover from his wounds and is eventually photographed. While the film breezes through this sequence, in reality, Peter spoke with the photographers and recounted the beatings that had caused his scars and his difficult recovery while in bondage, which is not shown in the film. Reportedly, in Peter's own words, he described how he had received the whippings from his plantation overseer Artayou Carrier, but that he does not remember the beatings or the immediate aftermath, suffering from memory loss.

As Peter described, it took two full months of physical recovery, and upon first waking he was plagued by a kind of madness. Though his recollections were cloudy, he said he'd been told by others that he was "sort of crazy" and had gotten ahold of a pistol and attempted to shoot those around him. Peter told his examiners, "I did not know that I had attempted to shoot everyone; they told me so. I burned up all my clothes; but I don't recall that." To make matters worse, Peter was told he had even tried to kill those closest to him, including his wife. Neither the abuse nor Peter's recovery are shown in the film, but his account became a key part of the feature that affected so many Americans who read his story.

Peter's escape from bondage

"Emancipation" portrays Peter's dramatic escape from his masters on John Lyons' (Timothy Hutton) plantation. In the film, he escapes with several others and spends days traversing forest and bayou, battling vicious dogs and even an alligator before arriving in Baton Rouge, where Union forces held camp. The true story chronicled in Harper's Weekly in 1863 describes Peter's long and arduous trek to freedom. In the film, Peter escaped with three fellow slaves and was chased by a group of "hunters" accompanied by bloodhound dogs. But another article, published in the New-York Daily Tribune in December of the same year, goes into even further detail.

This account described Peter's impressive ingenuity. It detailed how he led his group through different patches of water — including two trips through the dark, muddy Amite River — to attempt to throw off their pursuers. They also cleverly used not just onions — as in the film — but "strong-scented weeds" to mask their scent from the bloodhounds, spreading it over their skin after emerging from the water.

Unlike in the film, the newspaper account of their journey never suggests that Peter was separated from his companions, who it says arrived at a Union camp together. Upon reaching safety with Northern forces, the slaves were said to be in "feeble condition," with bloodied and swollen feet, and were given food and new clothes. Yet despite the horrors they'd endured, the group still found the strength to weep with joy.

He fought in the Union army

Though "Emancipation" does a good job of hammering home the intensity of Peter's harrowing journey to freedom, it's clear that at least some artistic license was taken for the sake of fitting Peter's story into a two-hour film. The movie truncates and omits many events described in contemporary accounts and invents a few more, most notably regarding Peter's service in the Union army.

In one well-chronicled incident, Peter was actually taken prisoner by Confederate soldiers. Once again in captivity, Peter was beaten further and left for dead by rebels. Astonishingly, Peter managed to survive and made a second daring escape, after which he came upon a Union camp in Baton Rouge. As described in the Harper's Weekly feature, Peter enlisted with the Corps D'Afrique, an all-Black regiment that in the film is referred to by its alternate name, the 1st Louisiana Native Guard. While the film hints that the Union soldiers could use his knowledge of the region, Peter is only ever shown serving as a uniformed soldier in a single assault, a fictionalized attack on his old plantation that leads to a dramatic reunion with his family. But according to Harper's and other sources, Peter continued fighting with the Corps D'Afrique well after the events depicted in the film, reportedly serving as a guide in several further engagements, including an assault on Port Hudson. Not much is known about Peter's service beyond that point.

The Emancipation Proclamation and Juneteenth

Despite the common belief that President Abraham Lincoln freed all the slaves with one sweeping gesture, his Emancipation Proclamation was more than a decade in the making. In fact, Lincoln expressed his belief in emancipation as early as 1849 (via PBS) but was convinced it could not be achieved in one fell swoop and should be a gradual process. He even believed that slaveowners of the day should receive recompense for losing slaves — many still viewed slaves as property and emancipation as theft.

The Civil War hastened Lincoln's objective. By late 1862, the President handed down an order that would instantly declare Southern slaves free if the Confederate states did not end their quarrel with the Union by January 1863. On the first of the new year, he signed the Emancipation Proclamation, but it only freed those slaves in Southern rebel states not under Union control. Part of its motivation was to achieve exactly what happened in "Emancipation" — to enlist Black men into the Union army (via PBS). Though many slaves, like Peter, fled to Union camps, countless others remained in bondage. It would not be until the end of the war that most slaves were freed thanks to the 13th Amendment, ratified in December 1865. For many slaves, news of the proclamation itself never even reached them, with those in Galveston, Texas, only discovering they were free on June 19, 1865, a date that is now a federal holiday known as Juneteenth.

Escaped slaves still had to earn their freedom

At a crucial moment in "Emancipation," Peter finally thinks he found freedom when he reaches Union forces in Baton Rouge. But to his indignation, the admitting officer declares that he is not free just yet; he is in an army camp, and he is technically "contraband" — confiscated property of a Southern state. To earn his freedom, he must enlist in the Union army and serve his country fighting against Confederate forces. This was not just true for Peter, but for untold numbers of slaves who believed they were free, only to be confronted with the unsettling knowledge that they still had to earn their freedom.

Prior to the signing of the 13th Amendment, slaves were still not technically free. But the Union Army desperately needed soldiers, and escaped slaves wanted freedom. Many former slaves enlisted with the hopes of returning from the experience as freed people. Scholar Jonathan Lande recounts how during the Civil War, as many as 180,000 African American men enlisted in the Union army to earn the right to be free. Unfortunately, they also discovered that even within the Northern territory and in the ranks of the army, racism and brutality persisted against Black men. In August 1861, a congressional act called for all property that aided in the Confederate cause to be confiscated — including slaves, since they were considered property. It did not include Northern slaves owned by those who supported the Union (per Encyclopedia.com), who remained slaves.

Who were the Corps d'Afrique?

When Peter is rescued by Union forces just outside Baton Rouge, he's found by a highly notable regiment known as the Native Guard. The Native Guard was a real fighting force from the period, among the first regiments to be comprised entirely of Black soldiers and freed slaves. Initially founded as a volunteer militia out of Louisiana during the colonial era, they were comprised of Black soldiers at a time when some slaves were afforded the right to earn freedom and be educated, own businesses, and become landowners.

For decades, this group was a key part of Louisiana's local defense forces, even taking part in the War of 1812, fighting in the Battle of New Orleans. At the outset of the Civil War, they even volunteered to fight for the South, forming into the regiment known as the Native Guard, but were refused by Confederate officials. When Union armies took the region during the Civil War, the Native Guard disbanded, but under the command of Capt. Andre Cailloux, they were reassembled to fight for the North after the Battle of Baton Rouge.

During the Civil War, the regiment was made up of both freedmen like Cailloux and escaped slaves like Peter. Initially, the Native Guard was used mostly for labor, but in May 1863, they played an active combat role, taking part in engagements at Port Hudson, Louisiana. Later that same year, additional regiments of Native Guards were brought together, forming the Corps D'Afrique.

Who took the Scourged Back photo and why?

Though the famous "Scourged Back" photograph plays a small part in "Emancipation," it inspired the film's production. "It was the first viral image of the brutality of slavery that the world saw," director Antoine Fuqua told Deadline. "Because of the journey it took me on, Peter's journey." The research from screenwriter William N. Collage began with the photograph, which was the work of Henry S. Gere, publisher of the Hampshire Gazette, and reformed slave-supporter Marshall Stearns. As explored by Civil War researcher Bruce Laurie, Gere was a fierce abolitionist, but Stearns was a soldier with little knowledge of or sympathy for slaves when he joined the army in 1862. In December 1862, however, Stearns found himself working at the Union army camp in Baton Rouge when Peter was discovered. Like many other white men at the camp, Stearns was shocked and dismayed by the sight of Peter's scars.

Gere called the sight of Peter's scars "one of the most horrid and singular objects I have ever beheld." Gere believed that an image of Peter needed to be captured and shared in the hopes that it could open people's eyes to the horrors of slavery. The pair took Peter to two portrait sessions in April 1863 with photographer William D. McPherson and his assistant, Mr. Oliver, and hastily made copies were given to soldiers to send to their families to help convince them of the righteousness of their fight (per The Boston Globe).

How did the Scouged Back photo make change?

Though today few would argue that slavery was anything but a cruel and barbaric practice, people of the 19th century in America who didn't live on plantations were largely unaware of its true horror. Many believed the Southern notion that slavery was an innocent and well-meaning practice, perhaps even a prosperous way of life for Black men and women. Thus, when the photograph of Peter was first published, it was met with shock and dismay from an outraged public, who had been almost entirely unaware of the brutality that slaves were subjected to (via The Boston Globe).

When the photo first spread, there were even Southern sympathizers who doubted that the image was real — or worse, some claimed that Peter had deserved his wounds. But for most people, the photo they saw published in Harper's Weekly was the first look at the consequences of slavery, and it opened their eyes to a stark reality. Ultimately, the photo was an uncomfortable but necessary sight that forced Americans who had not been swayed by the words of prominent abolitionists to confront that stark reality that was now hard to deny. Support for the Union cause increased as thousands upon thousands of people came away from viewing the image with the understanding that the war against the South was both justified and necessary.

Peter's family

The driving force of "Emancipation" is Peter's quest to escape to freedom, but it's also his unrelenting quest to be reunited with his wife (Charmaine Bingwa) and children. Separated from them after he is forcibly relocated to a new plantation, Peter fights his masters and makes a declaration to his distraught son that he will find his way back to them. Unfortunately, the true story of Peter does not include any such quest that history recorded, and very little is known about his own family. We know from a statement he made to his examiners as he was being photographed that he had a wife, but no mention is ever made of children. Likewise, historical accounts don't say whether he was ever motivated by a desire to reunite with his wife, whose real name remains unknown, nor whether she even survived to be found.

All we know for certain is that Peter fled from his plantation and was rescued by Union forces 10 days later, as he noted in his own remarks to photographers and medical assistants in Baton Rouge. That said, because we know that Peter had a wife, it is reasonable to believe that he may have had children, as slave owners regularly used threats of violence to persuade slaves to reproduce. The unfortunate reality, however, is that many babies born into slavery were separated from their mothers, as they were seen as little more than a sellable commodity (per The Washington Post).

Peter's fate and legacy

Despite the iconic and unforgettable image of the man who became known as "Whipped Peter" becoming an indelible part of Civil War history, even less is known about the remainder of his life than about his life prior to the photograph being taken. Many modern sources say that Peter served as a sergeant in the Second Louisiana Native Guard. It was during his service in the all-Black regiment that he took part in the unit's famous attack on Port Hudson in May 1863, though this has never been officially confirmed.

Still, while we know little about Peter's fate for certain, the enduring legacy of his life has continued to educate millions on one of America's darkest periods. The image's publication in Harper's Weekly and beyond sparked waves of outcry and effectively turned every Northerner with a heart and soul into an abolitionist. Thanks to new innovations in printing, it was reproduced as pocket-sized card stock images that allowed it to spread across the nation faster than any image in history (via The Boston Globe).

Since its initial printing, Peter and his famous photo also become noteworthy as an early example of the power of the emerging medium of photography, able to sway public opinion, and promote real social change. Today, we all recognize how important imagery can be on social media in illuminating injustice, and it all started with Peter and the "Scourged Back" photograph.